Daibutsuden (Great Buddha Hall), Tōdai-ji, Nara, Japan, 743, rebuilt c. 1700 (photo: author, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Built to impress, twice

When completed in the 740s, Tōdai-ji (or “Great Eastern Temple”) was the largest building project ever on Japanese soil. Its creation reflects the complex intermingling of Buddhism and politics in early Japan. When it was rebuilt in the twelfth century, it ushered in a new era of Shōguns and helped to found Japan’s most celebrated school of sculpture. It was built to impress. Twice.

Buddhism, Emperor Shomu and the creation of Tōdai-ji

The Great Buddha (Daibutsu), 17th century replacement of an 8th century sculpture, Tōdai-ji, Nara, Japan (photo: Deanna MacDonald, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The roots of Tōdai-ji are found in the arrival of Buddhism in Japan in the sixth century. Buddhism made its way from India along the Silk Route through Central Asia, China and Korea. Mahayana Buddhism was officially introduced to the Japanese Imperial court around 552 by an emissary from a Korean king who offered the Japanese Emperor Kimmei a gilded bronze statue of the Buddha, a copy of the Buddhist sutras (sacred writings) and a letter stating: “This doctrine can create religious merit and retribution without measure and bounds and so lead on to a full appreciation of the highest wisdom.”

Buddhism quickly became associated with the Imperial court whose members became the patrons of early Buddhist art and architecture. This connection between sacred and secular power would define Japan’s ruling elite for centuries to come. These early Buddhist projects also reveal the receptivity of Japan to foreign ideas and goods—as Buddhist monks and craftspeople came to Japan.

Buddhism’s influence grew in the Nara era (710–94) during the reign of Emperor Shōmu and his consort, Empress Komyo who fused Buddhist doctrine and political policy—promoting Buddhism as the protector of the state. In 741, reportedly following the Empress’ wishes, Shōmu ordered temples, monasteries and convents to be built throughout Japan’s 66 provinces. This national system of monasteries, known as the Kokubun-ji, would be under the jurisdiction of the new imperial Tōdai-ji (“Great Eastern Temple”) to be built in the capital of Nara.

Building Tōdai-ji

Why build on such an unprecedented scale? Emperor Shōmu’s motives seem to have been a mix of the spiritual and the pragmatic: in his bid to unite various Japanese clans under his centralized rule, Shōmu also promoted spiritual unity. Tōdai-ji would be the chief temple of the Kokubun-ji system and be the center of national ritual. Its construction brought together the best craftspeople in Japan with the latest building technology. It was architecture to impress—displaying the power, prestige and piety of the imperial house of Japan.

However the project was not without its critics. Every person in Japan was required to contribute through a special tax to its construction and the court chronicle, the Shoku Nihon-gi, notes that, “the people are made to suffer by the construction of Tōdai-ji and the clans worry over their suffering.”

Bronze Buddha

Tōdai-ji included the usual components of a Buddhist complex. At its symbolic heart was the massive hondō (main hall), also called the Daibutsuden (Great Buddha Hall), which when completed in 752, measured 50 meters by 86 meters and was supported by 84 massive cypress pillars. It held a huge bronze Buddha figure (the Daibutsu) created between 743 to 752. Subsequently, two nine-story pagodas, a lecture hall and quarters for the monks were added to the complex.

The Great Buddha (Daibutsu), 17th century replacement of an 8th century sculpture, Tōdai-ji, Nara, Japan (photo: throgers, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The statue was inspired by similar statues of the Buddha in China and was commissioned by Emperor Shōmu in 743. This colossal Buddha required all the available copper in Japan and workers used an estimated 163,000 cubic feet of charcoal to produce the metal alloy and form the bronze figure. It was completed in 749, though the snail-curl hair (one of the 32 signs of the Buddha’s divinity) took an additional two years.

Great Buddha, lotus petal (detail), 17th century replacement of an 8th century sculpture, Tōdai-ji, Nara, Japan

When completed, the entire Japanese court, government officials and Buddhist dignitaries from China and India attended the Buddha’s “eye-opening” ceremony. Overseen by the Empress Koken and attended by the retired Emperor Shōmu and Empress Komyo, an Indian monk named Bodhisena is recorded as painting in the Buddha’s eyes, symbolically imbuing it with life. The Emperor Shōmu himself is said to have sat in front of Great Buddha and vowed himself to be a servant of the Three Treasures of Buddhism: the Buddha, Buddhist Law, and Buddhist Monastic Community. No images of the ceremony survive but a Nara period scroll painting depicts a sole, humbly small figure at the Daibutsu‘s base suggesting its awe-inspiring presence.

The Daibutsu sits upon a bronze lotus petal pedestal that is engraved with images of the Shaka (the historical Buddha, known also as Shakyamuni) Buddha and varied Bodhisattvas (sacred beings). The petal surfaces are etched with fleshy figures with swelling chests, full faces and swirling drapery in a style typical of the elegant naturalism of Nara era imagery. The petals are the only reminders of the original statue, which was destroyed by fire in the twelfth century. Today’s statue is a seventeenth-century replacement but remains a revered figure with an annual ritual cleaning ceremony each August.

Chogen and the rebuilding of Tōdai-ji in the Kamakura Era (1185–1333)

The Genpei Civil War (1180–85) saw countless temples destroyed as Buddhist clergy took sides in clan warfare. Japan’s principal temple Tōdai-ji sided with the eventually victorious Minamoto clan but was burned by the soon-to-be defeated Taira clan in 1180.

The destruction of this revered Temple shocked Japan. At the war’s end, the reconstruction of Tōdai-ji was one of the first projects undertaken by Minamoto Yoritomo who, as the new ruling Shōgun, was eager to present the Minamoto as national saviors. The aristocracy and the warrior elite contributed funds and the Buddhist priest Shunjobo Chogen was placed in charge of reconstruction. Tōdai-ji again became the largest building project in Japan.

Brackets, Nandaimon (Great South Gate), end of the 12th century, Tōdai-ji, Nara, Japan (photo: Deanna MacDonald, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Chōgen was unique in his generation in that he made three trips to China between 1167–76. His experience of Song Dynasty Buddhist architecture inspired the rebuilding of the temples of Nara, in what became know as the “Great Buddha” or the “Indian” style.

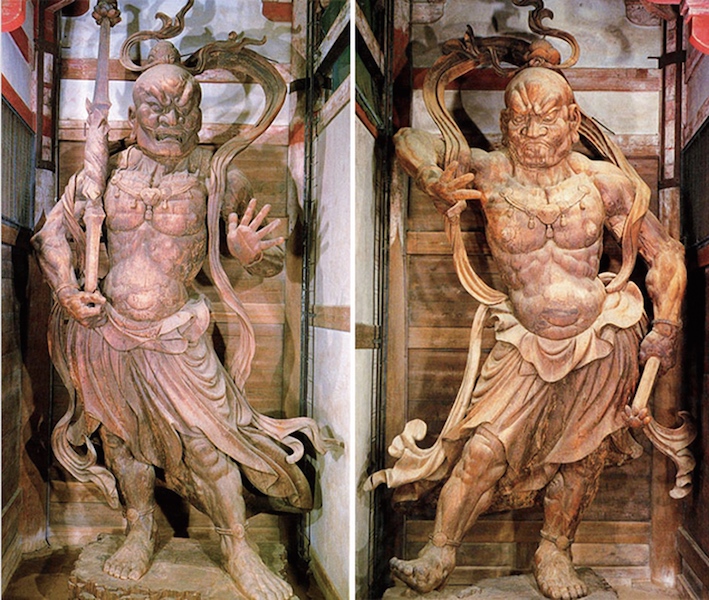

The key-surviving example of this style is Tōdai-ji’s Great South Gate—Nandaimon—which dates to 1199. An elaborate bracketing system supports the broad-eaved, two-tiered roof. The Nandaimon holds the 2 massive wooden sculptures of Guardian Kings (Kongō Rikishi) by masters of the Kei School of Sculpture.

Kei School of Sculpture

The large scale rebuilding after the Genpei Civil War created a multitude of commissions for builders, carpenters and sculptors. This concentration of talent led to the emergence of the Kei School of Ssculpture—considered by many to be the peak of Japanese sculpture. Noted for its austere realism and the dynamic muscularity of its figures, the Kei School reflects the Buddhism and warrior-centered culture of the Kamakura era (1185–1333).

Unkei is considered the leading figure of the Kei School, with a career spanning over 30 years. His distinctive style emerged in his work on the refurbishment of the many Nara temples/shrines, most particularly Tōdai-ji. Unkei’s fierce guardian figure Ungyō in the Nandaimon is typical of Unkei’s powerful, dynamic bodies. It stands in dramatic contrapposto opposite the other muscular Guardian King, Agyō, created with Kaikei and other Kei sculptors.

Left: Ungyō, right: Agyō, both c. 1203, Nandaimon (Great South Gate), Tōdai-ji Nara, Japan (Asahi Shimbun file photo)

Both figures are fashioned of cypress wood and stand over eight meters tall. They were made using the joint block technique (yosegi zukuri), that used eight or nine large wood blocks over which another layer of wooden planks were attached. The outer wood was then carved and painted. Only a few traces of color remain.

Ecology, craftsmanship, and early Buddhist art in Japan

The grand Buddhist architectural and sculptural projects of early Japan share a common material—wood—and are thus closely linked to the natural environment and to the long history of wood craftsmanship in Japan.

When Korean craftsmen brought Buddhist temple architecture to Japan in the sixth century, Japanese carpenters were already using complex wooden joints (instead of nails) to hold buildings together. The Koreans’ technology allowed for the support of larger, tile-roof structures that used brackets and sturdy foundation pillars to funnel weight to the ground. This technology ushered in a new, larger scale in Japanese architecture.

Monumental timber framed architecture requires enormous amounts of wood. The wood of choice was cypress, which grows up to forty meters tall and has a straight tight grain that easily splits into long beams and is resistant to rot.

The eighth-century campaign to construct Buddhist temples in every Japanese province under Imperial control (mostly in the Kinai area, today home to Osaka and Kyoto) is estimated to have resulted in the construction 600–850 temples using three million cubic meters of wood. As the years progressed Kinai’s old growth forests were exhausted and builders had to travel farther for wood.

By far the most prestigious and wood-demanding project was the Imperial monastery of Tōdai-ji. Eighth-century Tōdai-ji had two 9-story pagodas and a 50 x 86 meter great hall supported by 84 massive cypress pillars that used at least 2200 acres of local forest. After Tōdai-ji’s destruction in 1180, it was rebuilt under the supervision of the monk Chogen, who solicited aid from all over Western Japan. Builders had to travel hundreds of kilometers from Kinai to find suitable wood. Whole forests were cleared to find tall cypresses for pillars, which were then transported at great cost: 118 dams were built to raise river levels in order to transport the massive pillars. And that was only the pillars—wood for the rest of the structure came from at least ten provinces.

Tōdai-ji’s reconstructed main hall was only half the size of the original and its pagodas several stories shorter. The availability or scarcity of quality local wood was a major factor in the design and evolution of architecture in Japan. For example, the growing scarcity of cypress of structural dimensions led to innovations that allowed carpenters to work with less straight-grained woods, like red pine and zelkova.

Additional resources

Historic monuments of Ancient Nara (UNESCO).

Video from UNESCO on the great Buddha sculpture.

Japan, 500–100 A.D. on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.