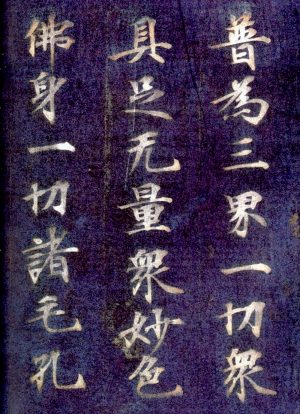

Fragment of the Flower Garland Sutra, known as Nigatsudō Burned Sutra 二月堂焼経, c. 744, silver ink on indigo-dyed paper, 9-3/4 inches high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Nara period (710–794 C.E.): The influence of Tang-dynasty Chinese culture

China’s Tang dynasty concentrated such a diverse range of foreign influences that its artistic and cultural characteristics are often referred to as the “Tang international style.” This style had a major impact in Japan as well. Featuring an eclectic and exuberant mix of Central Asian, Persian, Indian, and Southeast Asian motifs, Tang-dynasty visual culture comprised paintings, ceramics, metalware, and textiles.

As these foreign imports were shaping Chinese artistic expression at home, Tang-dynasty artifacts and techniques spread beyond China to neighboring states and along the Silk Road. In Japan, the lavish Tang style was intertwined with Buddhist devotional art.

Elegantly transcribed sutras, calligraphed in silver ink on indigo-dyed paper, exemplify this form of Tang-inspired Nara-period art. The painstaking practice of copying Buddhist sacred texts by using precious materials was deemed to earn spiritual merit for everyone involved, from those preparing the materials to the patrons.

The intermingling of political power and Buddhism in the Nara period found its utmost expression in the building of the “great eastern temple” or Tōdaiji and, within this temple, in the casting of the “great Buddha”—a gigantic bronze statue that stood approximately 15 meters/ 16 yards tall and necessitated all available copper in Japan to produce the casting metal.

The Great Buddha (daibutsu 大仏), 17th century replacement of an 8th century sculpture, Tōdai-ji, Nara, Japan (photo: throgers, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Although the current statue is a later replacement of the Nara-period artifact, it nonetheless suggests the effect of opulence and awe that it must have achieved in its day. Tōdaiji continued to transform and adapt through the centuries, but its identity is still inextricably linked to the grand scale and commensurate ambition of Nara-period culture.

Sociopolitical power was concentrated, during the Nara period, in the new Heijō capital (today’s city of Nara). Surrounded by Buddhist temples, the Heijō palace was the primary site of imperial power. It also housed subsidiary ministries, modeled on the Chinese centralized government. Generous spaces characterized the palace complex. These spaces accommodated outdoor celebrations, like those of the New Year, but also served to emphasize a sense of distance and therefore the due reverence to the emperor. The palace complex was designed to separate the realm of the emperor from the outside world. That principle of separation was reflected within the palace compound itself, where the emperor’s living quarters were set apart from government buildings. The architectural configuration of the palace reflected the hierarchical configuration of power.

Little of the palace survives today, as various structures within the complex suffered the vicissitudes of nature and history, while others were transferred to the new capital, Heian, for which the next period was named.

Additional resources:

For information on other periods in the arts of Japan, see the longer introductory essays here:

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Jomon to Heian periods

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Kamakura to Azuchi-Momoyama periods

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Edo period

A brief history of the arts of Japan: the Meiji to Reiwa periods

JAANUS, an online dictionary of terms of Japanese arts and architecture

e-Museum, database of artifacts designated in Japan as national treasures and important cultural properties

On Japan in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Richard Bowring, Peter Kornicki, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993)