Black Mountain College: A highly influential school founded in North Carolina in 1933 where teaching was experimental and committed to an interdisciplinary approach.

Read Now >Chapter 73

Itinerant modernisms: cosmopolitans, exiles, travelers since 1950

Introduction

To be itinerant is to be on the move—to journey from one place another. In the second half of the twentieth century, the large-scale migrations of artists, ideas, and visual forms had an enormous impact on the evolution and practice of contemporary art worldwide. Some artists traveled as exiles or refugees, fleeing censorship and violent oppression. Others were expatriates or emigrants, seeking opportunity and new experience through voluntary relocation. All of this movement has made it challenging to use established organizational modes that group artists by categories such as geography or cultural identity. This was made even more difficult since so much had shifted after World War II, when decolonization movements re-structured the geo-political boundaries of many regions, complicating how we understand art and artists of this time. And amidst the century’s many geopolitical restructurings, cities like Bamako, Calcutta, and Brasilia emerged as hubs for internationalism, while artists from once colonized parts of the world formed networks in Western metropoles such as New York, Paris, and London. Even when artists remained in place, their subjects and styles were sometimes impacted by the arrival of global material culture in their home locale.

Ibrahim el Salahi attended art school in London and took part in the international Mbari workshop in Ibadan, Nigeria, while his own work reflects Sudan’s (his home country) position as a site of cultural crossroads. Ibrahim El-Salahi, Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams, enamel and oil on cotton, 258.8 x 260 cm (Tate, London)

Through the blanket-term “itinerant,” this chapter considers vastly different kinds of artistic circulations—be they people, techniques, stylistic elements, or ideas, as well as movements both to and from places that have been marked as “central” or “peripheral” by the traditionally Eurocentric discipline of art history. Scholars have recently pointed out that the term “Postwar,” which is commonly used to designate this period in art history, inadvertently centers Western Europe and the United States within a narrative that is markedly more global (since it refers to the period after World War II—a war involving Europe and the United States). The decades following the 1940s also witnessed a range of parallel historical landmarks beyond Europe: decolonization movements in South Asia, Africa, and West Asia; dictatorships and civil wars worldwide; the ascent of socialism and the effects of the Cold War—each impacted the course of art history in their own ways.

How might an emphasis on itinerancy and migration challenge our understanding of 20th-century artworks, or how they fit into art historical narratives? Postwar American art, for example, might be recast as transnational when it is grounded in sites such as Black Mountain College in North Carolina, an experimental school that became a magnet for international artists in the mid-twentieth century—many of them displaced by war or conditions of persecution. The sections of this chapter do not constitute a comprehensive survey, but rather consider but a few of the various connections or encounters that lay the foundation for later artistic movements of the mid-to-late twentieth century.

Ruth Asawa, Untitled, c. 1958, iron wire, 219.7 × 81.3 × 81.3 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

Postwar Émigrés and Black Mountain College

Nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, Black Mountain College was an experimental art school that was operational from just 1933–57. With an interdisciplinary curriculum focused on encouraging independent thinking, its campus was home to an eclectic community of fine artists, performers, dancers, and musicians. Importantly, Black Mountain also became a hub for displaced or migrant artists, many of whom fled Nazi persecution and other totalitarian regimes during World War II.

One of the most interesting facts about Black Mountain is that it is not associated with any one genre or style. Those who passed through the College during its 24-year history include renowned artists with markedly global roots, and whose practices are now associated with many different early and mid-century movements. In this section, you’ll learn about a few of these key figures, whose legacies will be felt throughout the chapters that follow.

Essays and videos about postwar émigrés and Black Mountain College

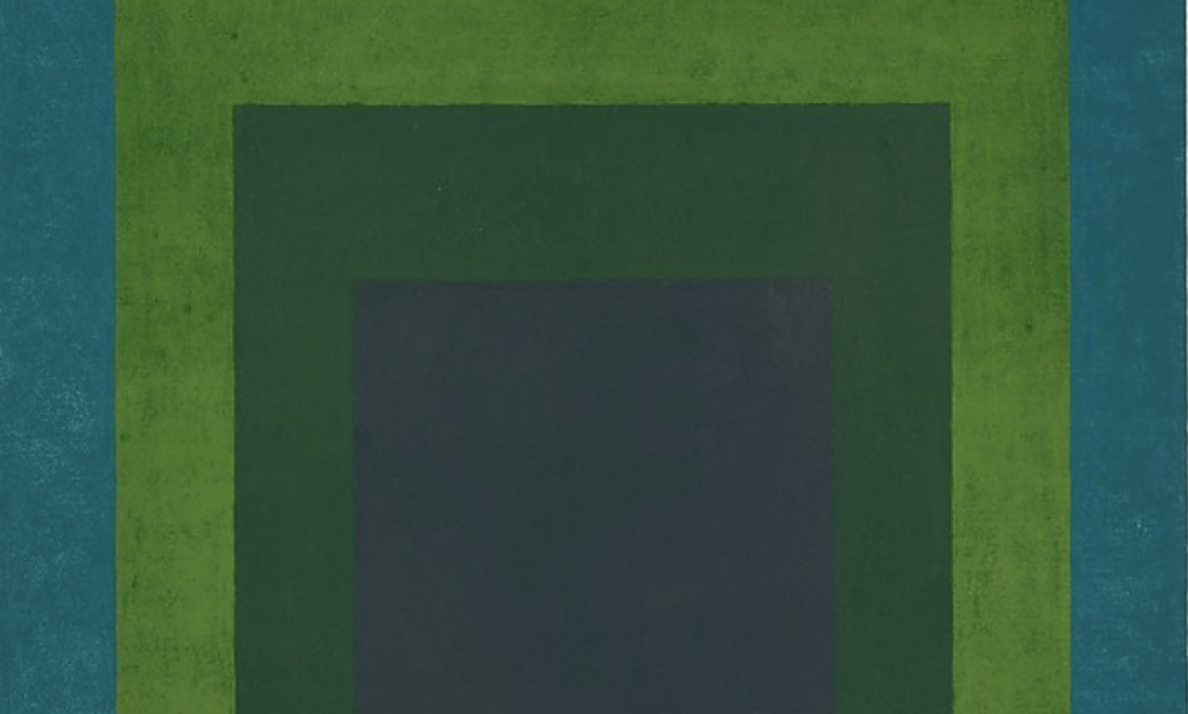

Josef Albers, Homage to the Square: An encouraging but strict teacher, Albers brought Bauhaus ideas from Germany to the United States. As a teacher at Black Mountain college, he introduced his disciplined approach to color theory to the next generation of the artistic vanguard in America.

Read Now >

Ruth Asawa, Untitled: Taking cues from Mexican basket-weaving, Asawa creates diaphanous abstract forms from woven wire. Asawa studied at Black Mountain College from 1946 to 1949.

Read Now >

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series: Lawrence carefully documents the migration of African Americans from the agricultural South to the industrial North. In 1946, Lawrence taught at the Summer Art Institute at Black Mountain College.

Read Now >

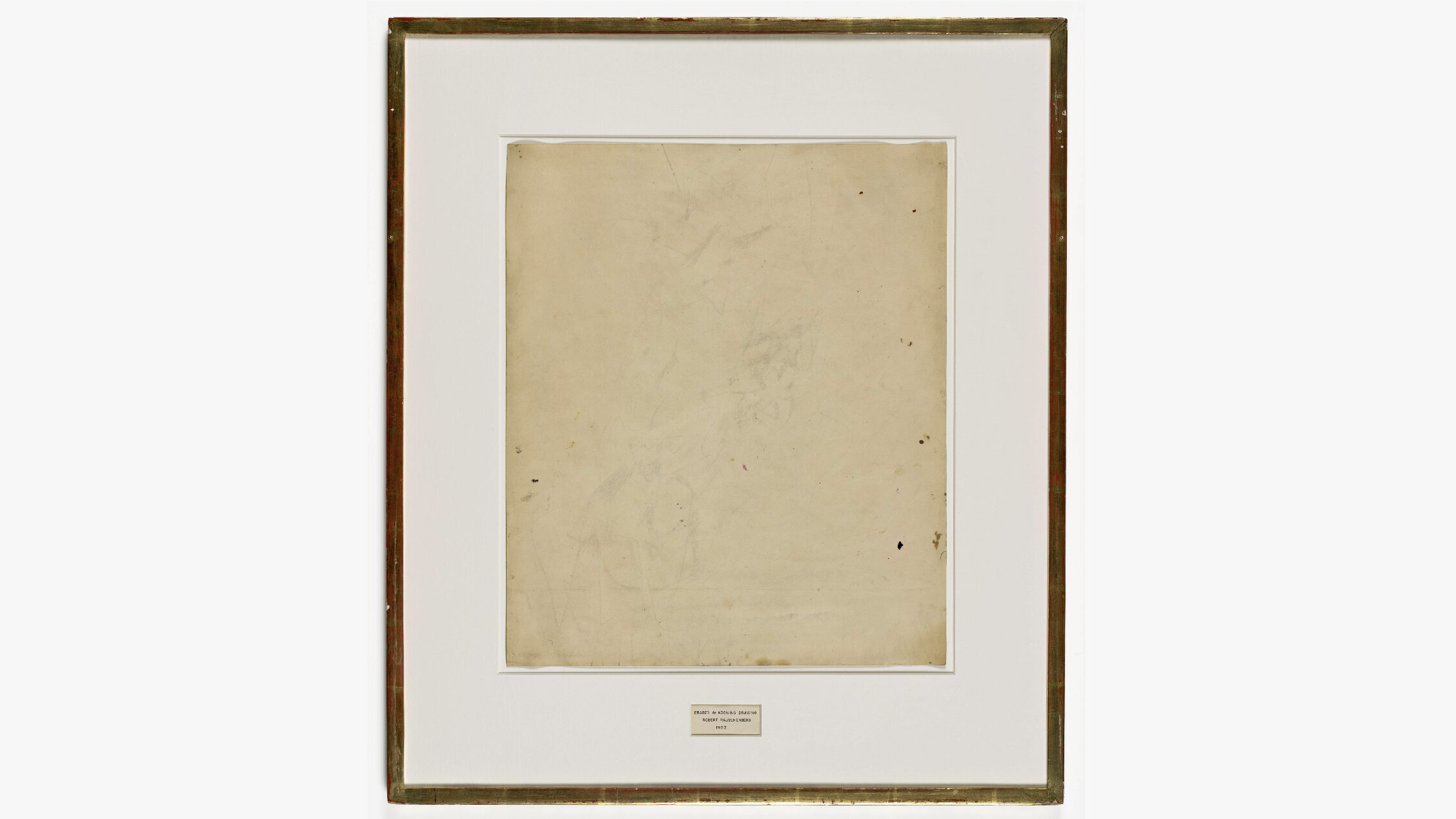

Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning drawing: When an artist erases another artist’s drawing, is it still a drawing, and whose? This work challenges the art definitions and contexts of its time. Robert Rauschenberg was a student, teacher and artist-in-residence for the several years at Black Mountain College.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Postcolonial Modernisms

In the mid-20th century, many parts of the world that had been colonized by European empires finally gained independence—whether through political treaty or armed liberation struggle. In the years between the end of World War II and the early 1960s, for instance, nearly forty African nation-states were born.

Artists who lived through these momentous transitions often grappled with the difficult task of establishing a post-colonial artistic style—one that looked ahead to an optimistic future, but also recovered or paid homage to local cultural forms that had been erased under colonization. At the same time, artists incorporated the relatively new forms that had been introduced by such conditions.

![Seydou Keïta, Untitled [Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress], 1956, printed 1997, Mali, Bamako, gelatin silver print, 60.96 x 50.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/hb_1997.364.jpg)

Seydou Keïta, Untitled [Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress], 1956, printed 1997, Mali, Bamako, gelatin silver print, 60.96 x 50.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A wide range of new styles emerged in the era of decolonization across Africa, South Asia, and West Asia. As you will learn about in the essays and videos below, Sudanese artist Ibrahim el-Salahi, Malian photographer Seydou Keïta, and Turkish artist—and Princess!—Fahrelnissa Zeid created artworks that blended both local and global influences in vastly different ways. For instance, while el-Salahi’s art was nurtured by his European training as well as the diverse cultural histories (both ancient and contemporary) that were present in his home country, Keïta’s photographs showed how everyday people living in Bamako, Mali resisted the imposition of Western culture under French colonization, but also creatively fused outside styles, ideas, and objects with their own African identities.

Essays and videos about postcolonial modernisms

![Seydou Keïta, Untitled [Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress], 1956, printed 1997, Mali, Bamako, gelatin silver print, 60.96 x 50.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/screen-shot-2016-10-15-at-8-42-48-am.png)

Seydou Keïta, Untitled (Seated Woman with Chevron Print Dress): Studio photography produced mementos for the growing middle class, with Keïta’s Bamako studio abuzz with clients.

Read Now >

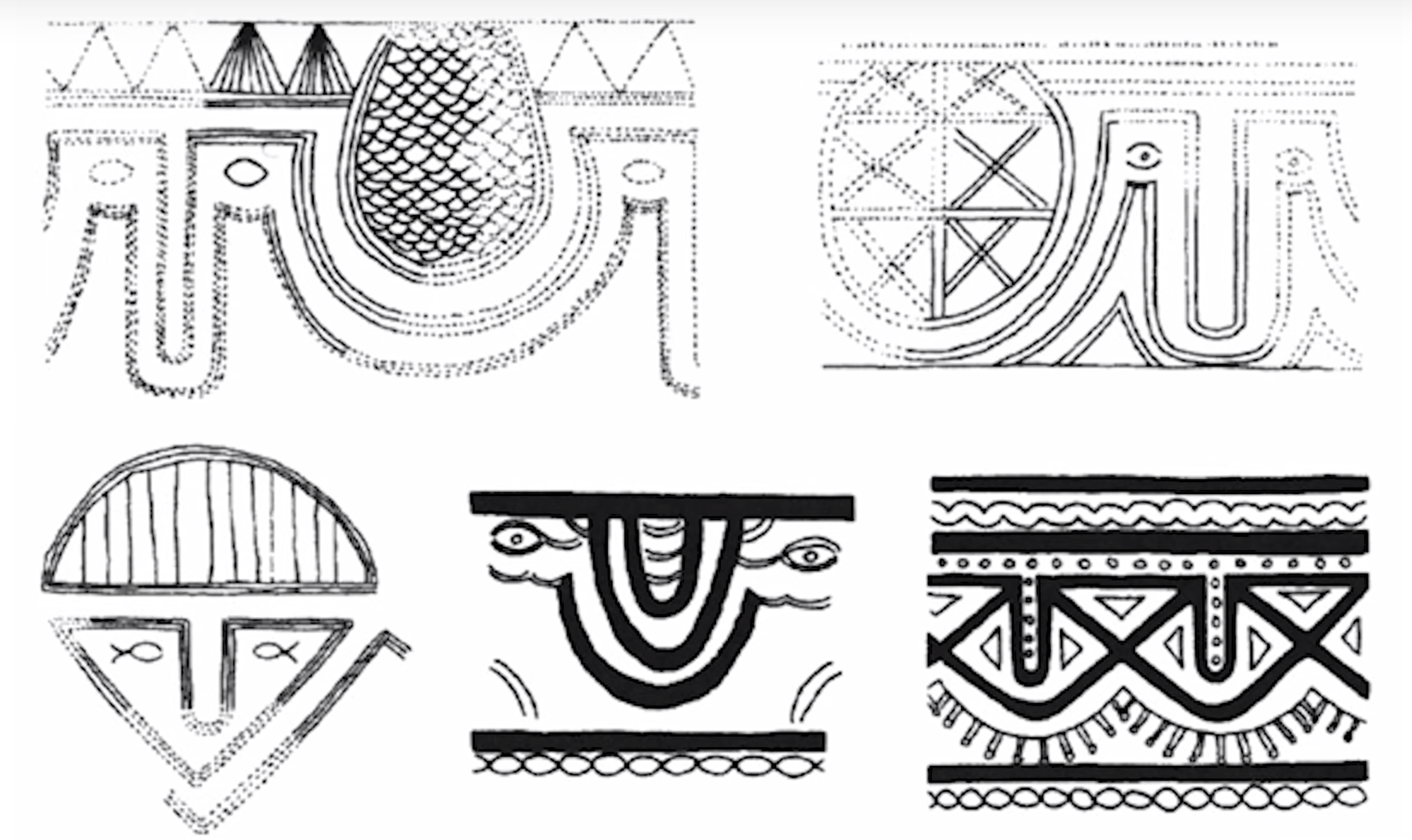

Uche Okeke: He learned uli, an Igbo female painting tradition, from his mother, and infused it with a modern sensibility.

Read Now >

Ibrahim El-Salahi, Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams: How would you paint a picture of something that’s not quite representable—like the sound of voices chanting, a spiritual vision, a childhood memory, or a dream that you can’t remember?

Read Now >

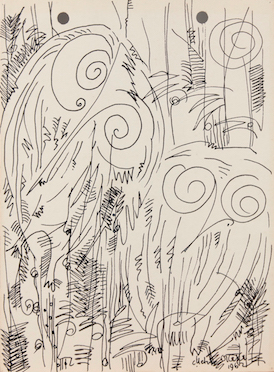

Skunder Boghossian, Night Flight of Dread and Delight: Boghossian’s exposure to Pan-Africanist networks in Paris helped him to develop the concept of his painting Night Flight of Dread and Delight.

Read Now >

Fahrelnissa Zeid: Turkish Princess and artist Zeid is best known for her large-scale abstract compositions blending Byzantine, Islamic, and Western influences.

Read Now >/5 Completed

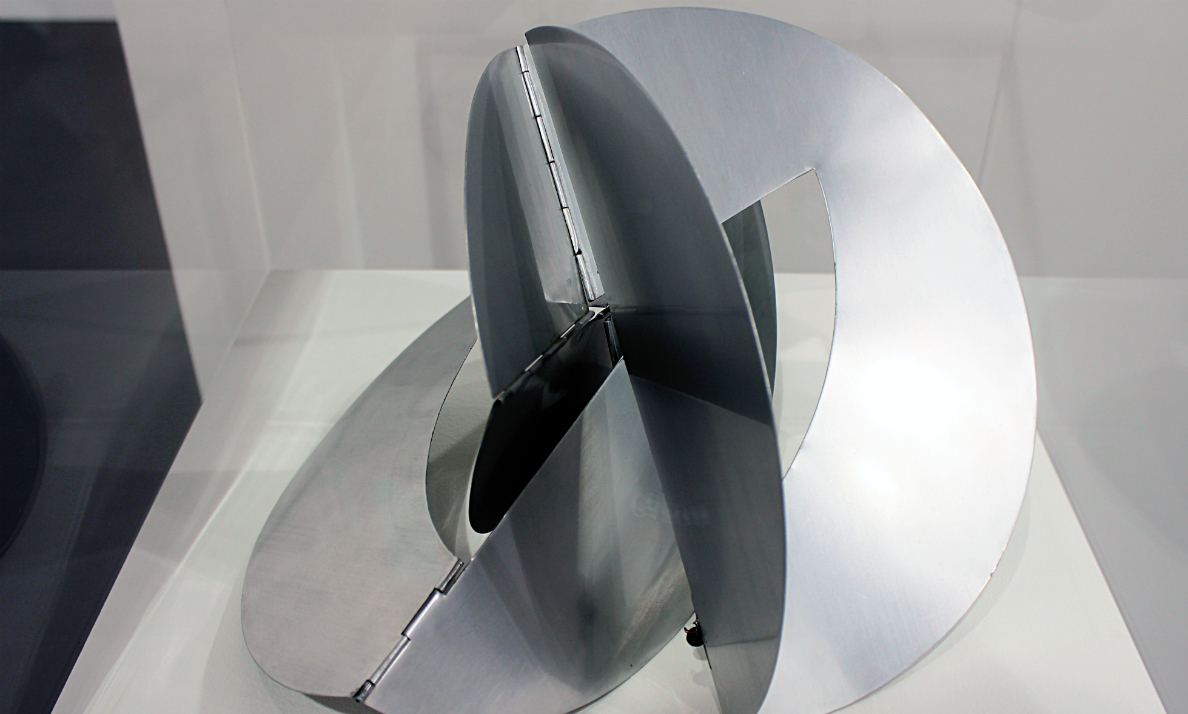

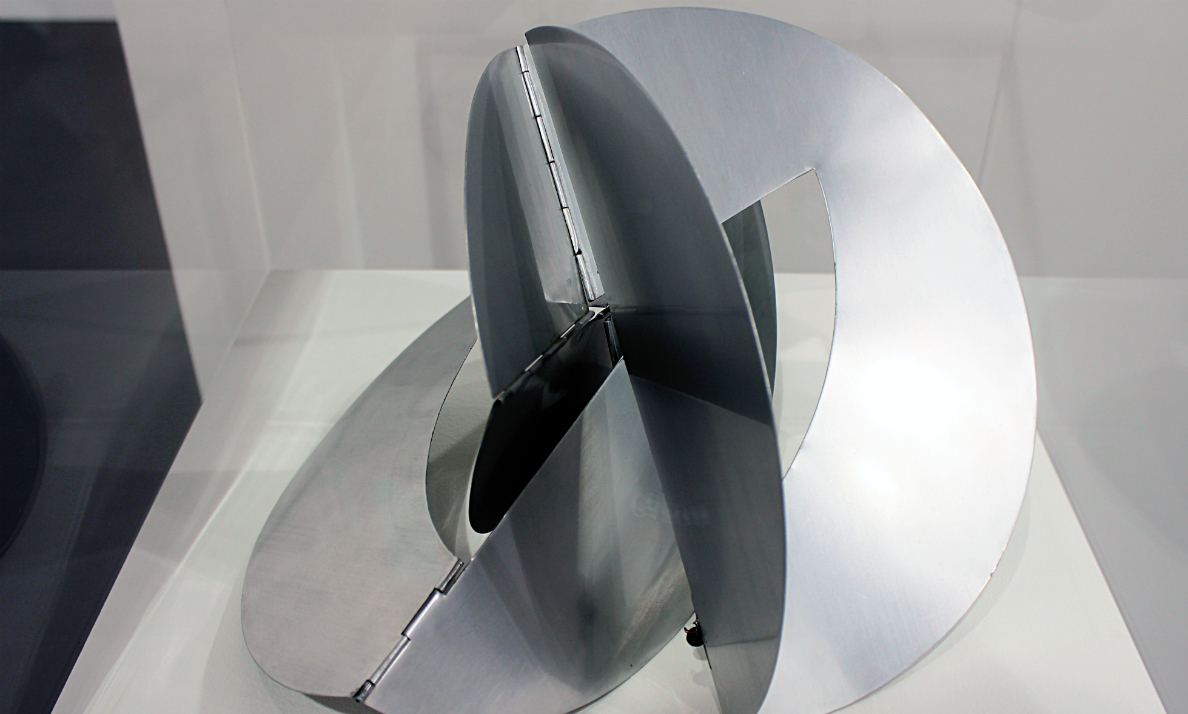

Lygia Clark, Bicho, 1962, aluminum (photo: trevor.patt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Abstraction and Reorientation in Latin American Art

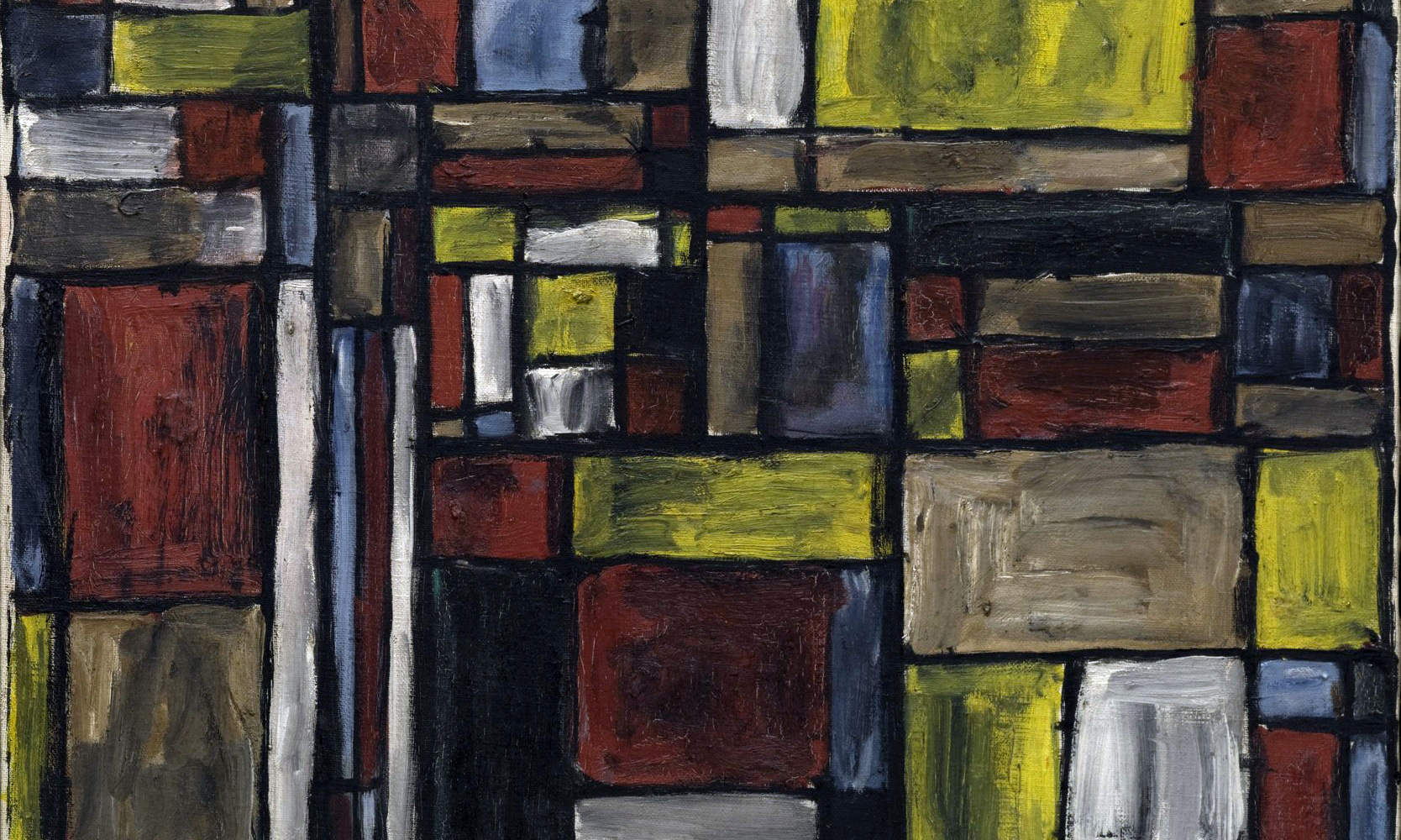

Most accounts of modern art history locate abstraction as a specifically Western invention, tracing this form to European modernists like Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich in the early twentieth century. Many twentieth-century artists in Latin America sought to prove that this wan’t the full story. When Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García returned home from a long sojourn in Paris, he came upon a profound realization: the geometric forms and abstract gridded patterns so often associated with European modernist painting were also everywhere to be found in pre-Columbian South America. Abstraction did not belong exclusively to Europe, in fact, but could also be found throughout the Americas and other parts of the world. From Uruguay and Brazil to Venezuela and Argentina, mid-twentieth century artists in South America experimented with abstraction in inventive ways. Torres-García’s work, and the others in this chapter, beg the question: How do these examples challenge art-historical perspectives on stylistic lineage and histories of form?

Essays and videos about abstraction and reorientation in Latin American art

Geometric Abstraction in South America, an introduction: Latin American geometric abstraction united international principles of modernist abstraction with local cultural traditions, and led to more participatory forms of art.

Read Now >

International Style architecture in Mexico and Brazil: Modern architecture in Mexico and Brazil adapted the ideas of Le Corbusier in surprising and important ways.

Read Now >

Lygia Clark, Bicho: Described by Clark as a “non object,” Bicho can take many shapes, and is manipulated by the viewer.

Read Now >

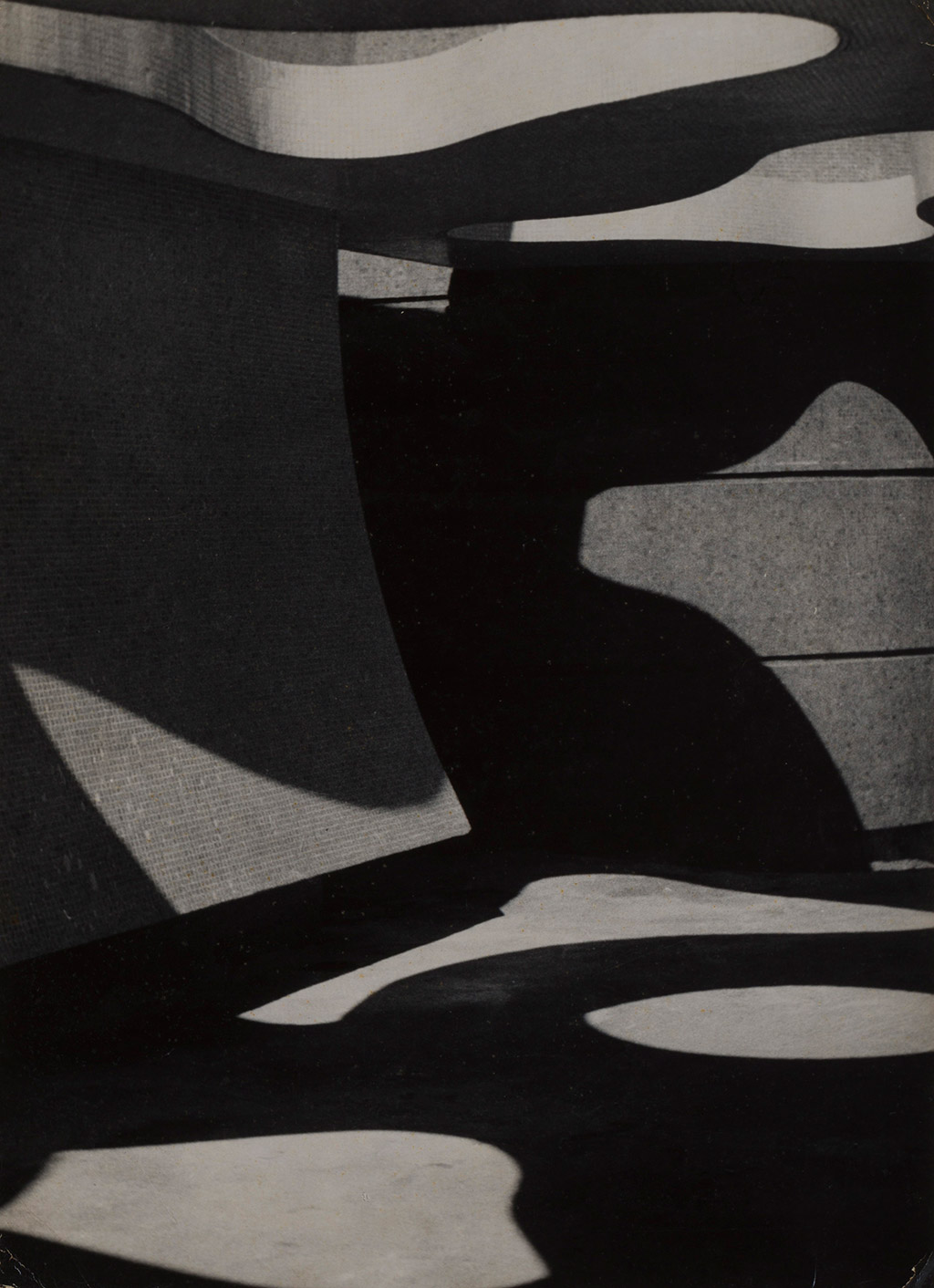

José Yalenti, Architecture or Twilight: Two important media were intertwined in 1950s Brazil, architecture and photography.

Read Now >/5 Completed

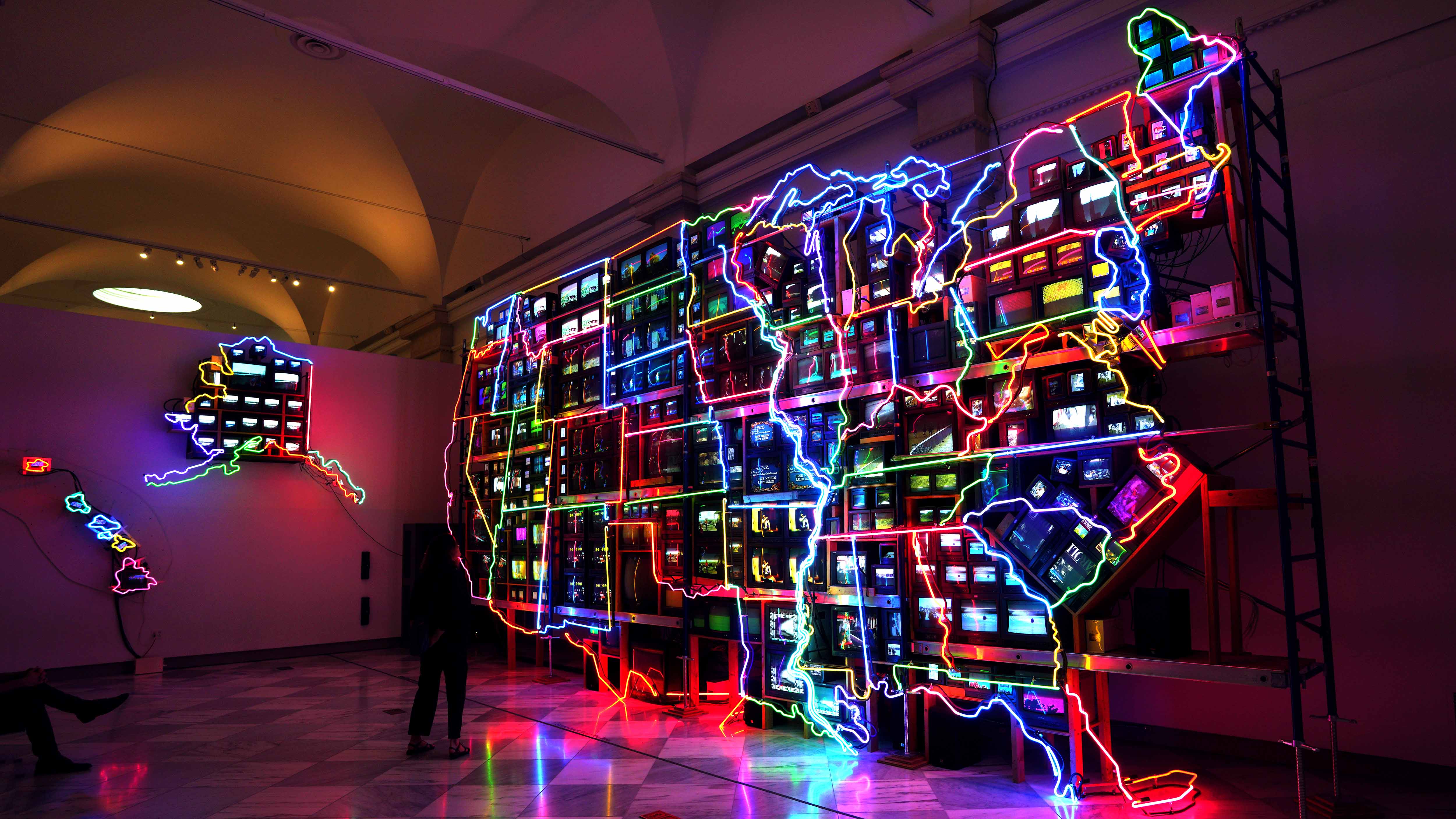

Nam June Paik, Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, 1995, fifty-one channel video installation (including one closed-circuit television feed), custom electronics, neon lighting, steel and wood; color, sound, approx. 15 x 40 x 4′ (Smithsonian American Art Museum) (© Nam June Paik Estate)

Contemporary Connections: Art and Migration Now

This chapter has focused on art of the 1940s–60s, an era defined by postwar and postcolonial migrations that had an enormous impact on art history worldwide. Today, artists continue to reflect on experiences and histories of travel, exile, and immigration both past and present. Artists of the later twentieth and early twenty-first centuries offer a potential point of dialogue with those earlier histories. For instance, new media artist Nam June Paik was born in Seoul, Korea but fled to Hong Kong during the Korean War in the 1950s. He was educated in Japan and West Germany, and spent much of his career in the United States. Paik’s international experience was immensely influential on his work, which often explored issues of connectivity and global understanding. Other contemporary artists like Yinka Shonibare MBE and Zineb Sedira likewise make work that reflects on their own experiences living or moving between regions connected by histories of colonialism, as well as how such histories are expressed through forms such as language and textiles.

Essays and videos about art and migration now

Nam June Paik, Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii: The “father of video art” argued that electronic communication, not transportation, unites the modern world.

Read Now >

Zineb Sedira: Born in Paris to Algerian parents, her works are often autobiographical, addressing issues of cultural identity and the personal consequences of migration.

Read Now >

Yinka Shonibare, The Swing (After Fragonard): Loaded with references to the French Revolution, the Age of Enlightenment and colonial expansion into Africa, Shonibare asks us to consider how a simple act of leisure can be so controversial.

Read Now >/4 Completed

What can we learn from these artists’ transnational journeys, and how might they lead us towards a new understanding of the art of both the past and present?

Key questions to guide your reading

How did the Post-war influx of emigrants to the United States impact the development of American art?

How did twentieth-century artists in Latin America, Asia, and Africa integrate local, global, and colonial influences in their work in different ways? What were their goals—To subvert? To honor? To recover? To invent?

What can we learn about lived experiences and histories of migration through works of contemporary art?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did the Post-war influx of emigrants to the United States impact the development of American art?

How did twentieth-century artists in Latin America, Asia, and Africa integrate local, global, and colonial influences in their work in different ways? What were their goals—To subvert? To honor? To recover? To invent?

What can we learn about lived experiences and histories of migration through works of contemporary art?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Black Mountain College

colonialism

Concrete Art (Brazil)

Constructive Universalism (Uruguay)

diaspora

exile

Fluxus

International Style

migration

Natural Synthesis (Nigeria)

Négritude

Neo-Concrete Art (Nigeria)

Neo-Dada

Pan-Africanism

postcolonialism