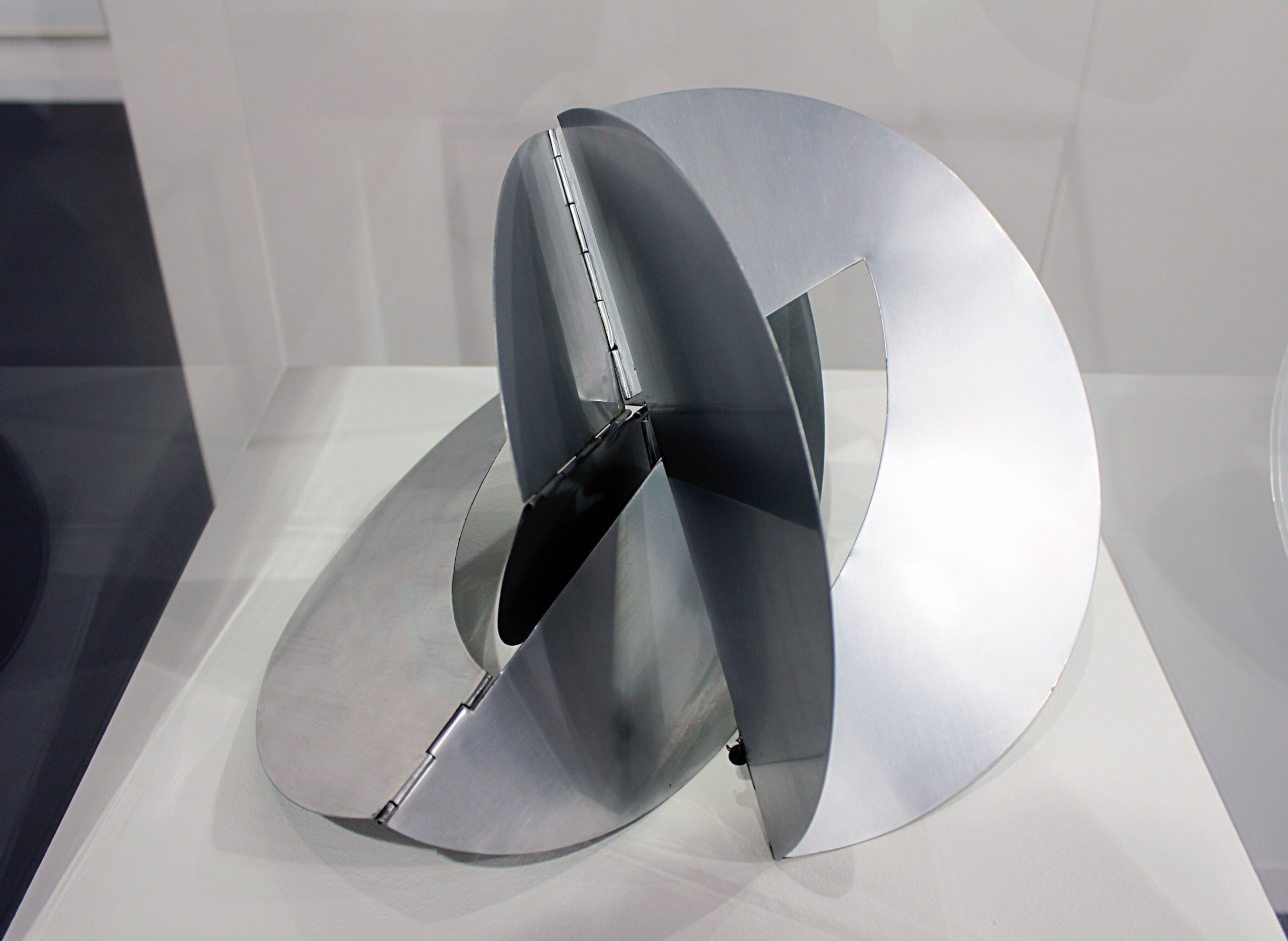

Lygia Clark, Bicho (Critter), 1962, aluminum (photo: trevor.patt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Fold, turn, close, open

When you think of sculpture, you might think of an ancient Roman emperor or a bronze military hero, both of which exemplify the principles of traditional sculpture: idealism and permanence. Bicho (Critter), a sculpture by Lygia Clark, defies these ideas of sculpture as a static idealized form. The viewer can fold, turn, close, and open Bicho, exploring its multifaceted nature. Consisting of geometric shapes connected through hinges, Lygia Clark created a sculpture that was not only participatory, but also seemingly infinite in its variability.

Neoconcretism

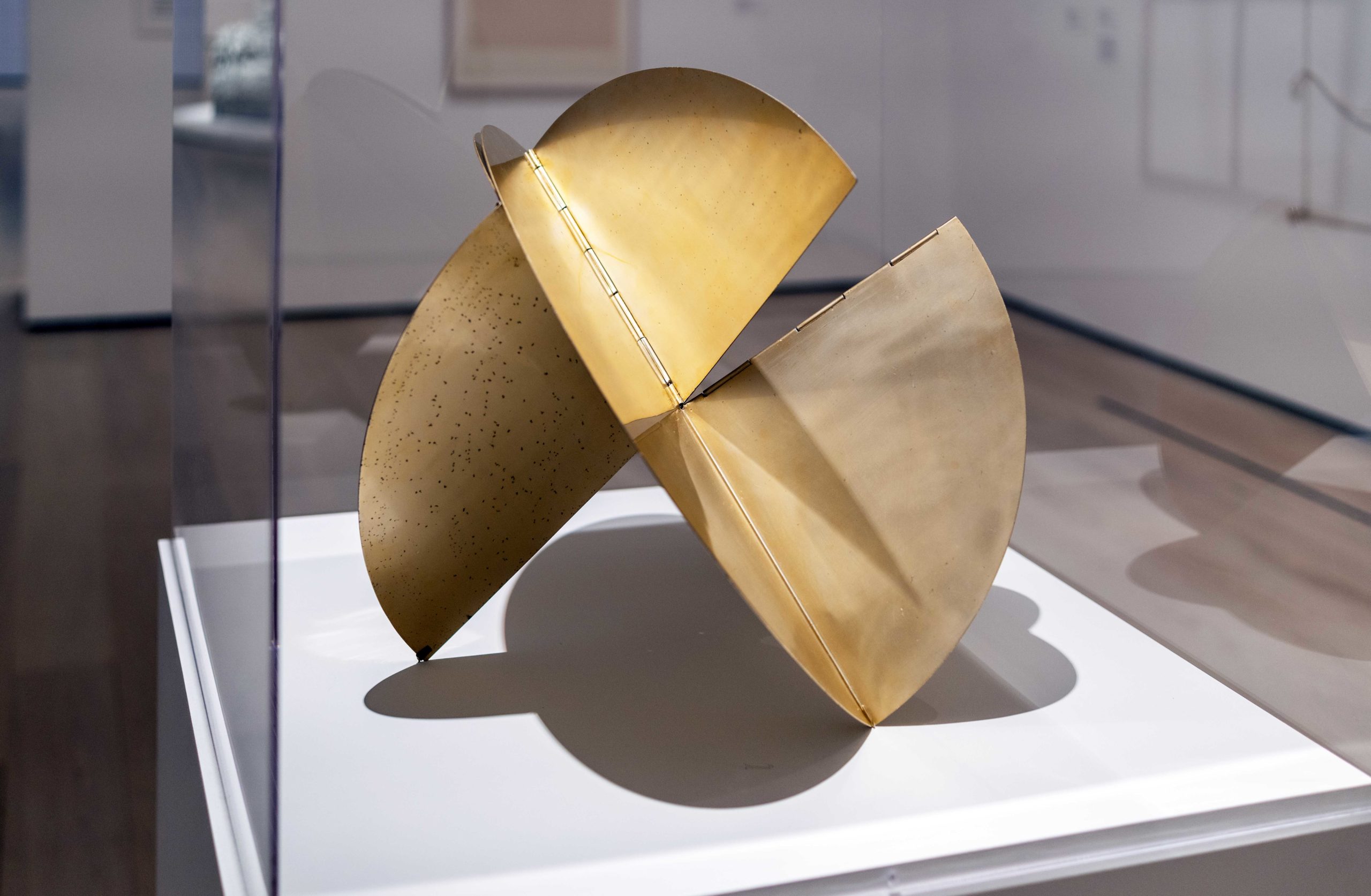

Lygia Clark, Sundial, 1960, aluminum with gold patina (The Museum of Modern Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In 1951, abstract art took on new meaning and form in Brazil, largely through the impact of a retrospective of the Bauhaus-trained artist Max Bill in São Paulo and the first São Paulo biennale. Throughout the 1950s, Bill’s influence in Brazil led to the development of concrete art, a kind of abstract art, which championed universal subjects like order and rationality, founded on objectivity and science. Together with Hélio Oiticica and other artists from Rio de Janeiro, however, Clark articulated her ideas about this kind of abstraction in the 1959 “Neoconcrete Manifesto” (or “Manifesto Neoconcreto”). In it, the artists declared their break from the tenets of concrete art with its systematic approach to abstraction. Clark, on the other hand, sought a freer and more organic interpretation of geometric abstraction, effectively eliminating the demarcation between two-dimensional and three-dimensional form.

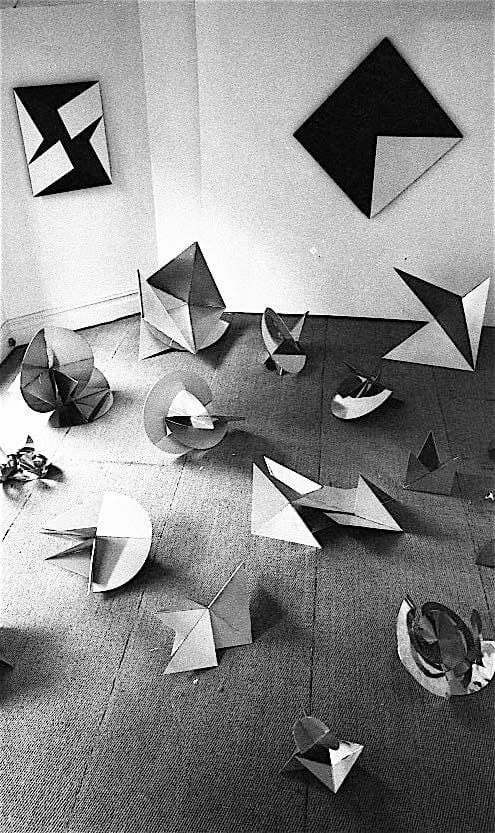

Lygia Clark, Bicho-Maquete (Creature-Maquette) (320), 1964, aluminum (Tate, London)

We see the organic nature of Bicho, in keeping with the ideas of neoconcretism, not only in its exoskeletal form and transformative nature, but also in its name. Whereas traditional sculpture hides its structural support, Clark instead focuses on it, by drawing attention to the hinges that bind the work together, and to the empty spaces created in between these folded spaces. As seen in Bicho, the straight-edged and round shapes recall skeletal forms while the hinges function as spinal columns. Even the name, Critter, recalls natural life, as if the work were a living creature meant to be animated—or better yet mutated—by the participant.

Installation view, Lygia Clark’s Bichos, 1965 (photo: yigruzeltil)

Participation and experience

Clark made these sculptures to be participatory, and therefore variable. Created as a series, there are around seventy Bichos in total. She challenged not only the idea that sculpture is fixed, but also that there is only one way to view or experience it. The sculptures are fundamentally unstable—both literally and metaphorically. They have no front or back, no inside or outside, no left or right. In this way, they have no author, since each participant creates a different experience of Bicho. Different from performance art however, these sculptures do not create spectacle, but rather invite participation. The work of art is not the viewing of the sculpture itself, but one’s participation with it.

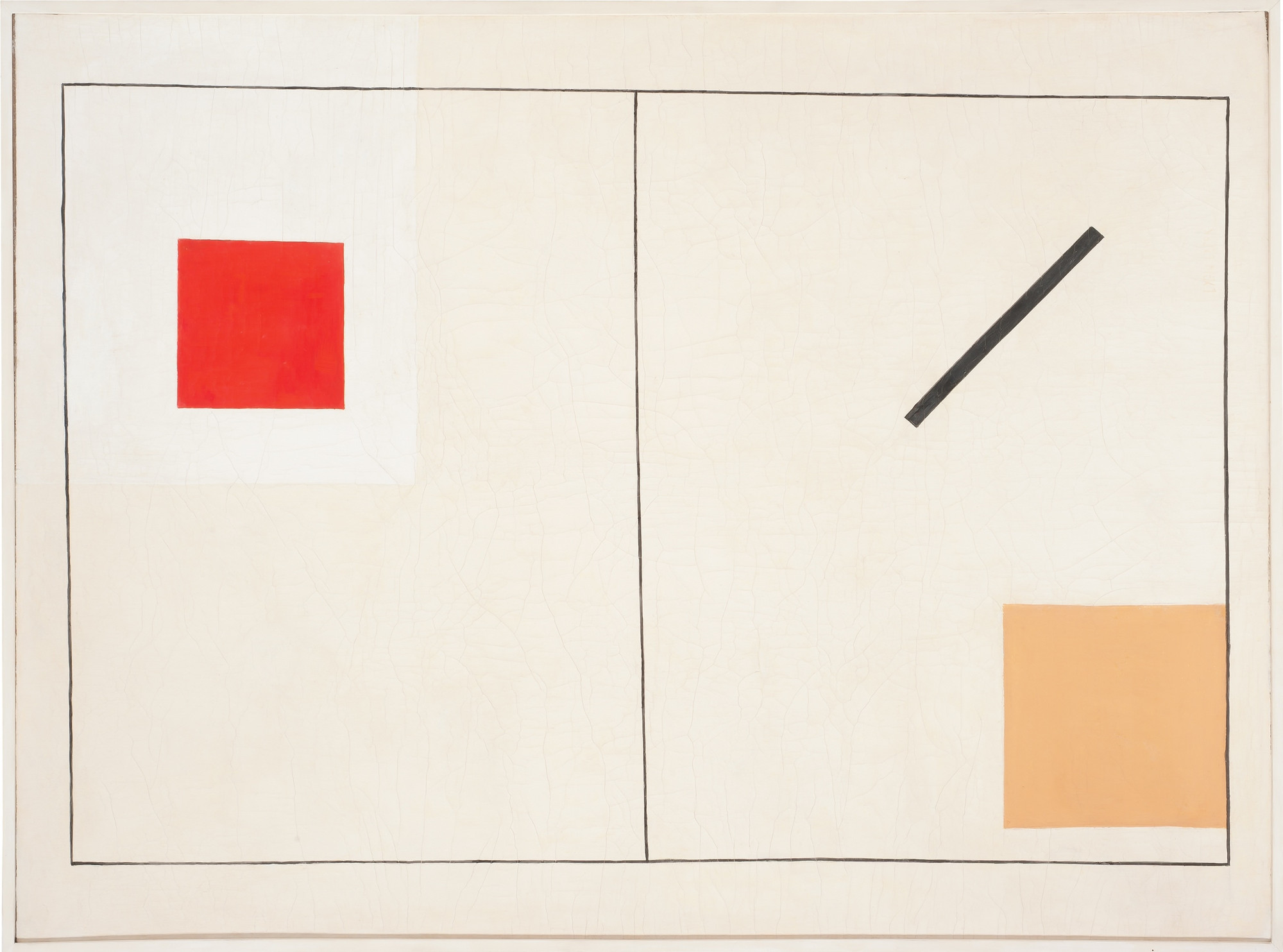

Lygia Clark, Descoberta da linha orgânica (Discovery of the Organic Line), 1954, oil on canvas (Private collection)

A “non-object”

In exploring painting, particularly the space between the painting and frame, Clark discovered what she referred to as the “organic line.” She arrived at this conceptual idea when she looked at a door and noticed that the door and its frame are one. She observed that the gap in-between is a connective line that visually integrates the two into a single whole. Descoberta da linha orgânica (Discovery of the Organic Line) illustrates this idea, since it is the painting within a painting that calls attention to the line itself.

Clark arrived at Bicho through her exploration of the “organic line,” and its mutability in two and three-dimensional form. However, it was Ferreira Gullar, primary author of the “Neoconcrete Manifesto” who called Bicho neither painting nor sculpture. Instead, Gullar described the work as a non-object (an early phrase for abstraction) that did not have a function and that resisted categorization.