The “father of video art” argued that electronic communication, not transportation, unites the modern world.

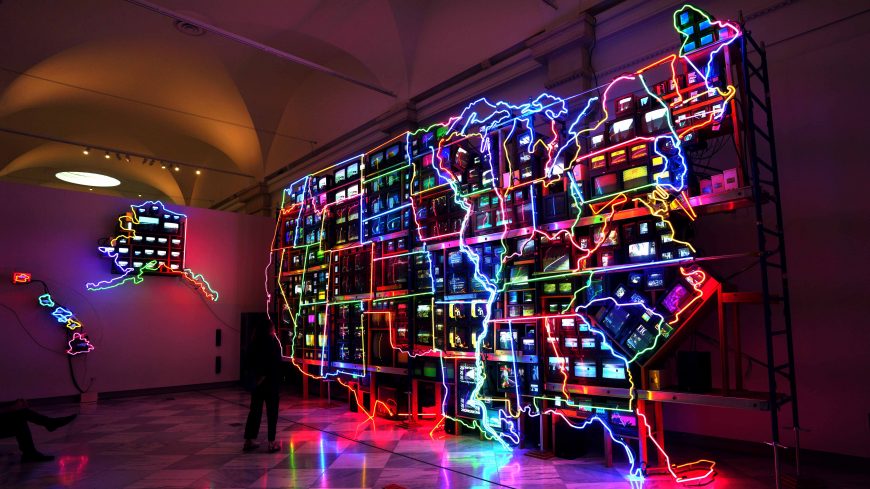

“Preserving Nam June Paik’s Electronic Superhighway.” Nam June Paik, Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, 1995, fifty-one channel video installation (including one closed-circuit television feed), custom electronics, neon lighting, steel and wood; color, sound, roughly 15 x 40 x 4 feet (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.) © Nam June Paik Estate. Speakers: Dan Finn and Dr. Steven Zucker

Getting on the “Electronic Super Highway”

In 1974, artist Nam June Paik submitted a report to the Art Program of the Rockefeller Foundation, one of the first organizations to support artists working with new media, including television and video. Entitled “Media Planning for the Post Industrial Society—The 21st Century is now only 26 years away,” the report argued that media technologies would become increasingly prevalent in American society, and should be used to address pressing social problems, such as racial segregation, the modernization of the economy, and environmental pollution. Presciently, Paik’s report forecasted the emergence of what he called a “broadband communication network”—or “electronic super highway”—comprising not only television and video, but also “audio cassettes, telex, data pooling, continental satellites, micro-fiches, private microwaves and eventually, fiber optics on laser frequencies.” By the 1990s, Paik’s concept of an information “superhighway” had become associated with a new “world wide web” of electronic communication then emerging—just as he had predicted.

Nam June Paik, Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, 1995, fifty-one channel video installation (including one closed-circuit television feed), custom electronics, neon lighting, steel and wood; color, sound, roughly 15 x 40 x 4 feet (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) © Nam June Paik Estate

From music to Fluxus

Paik was well-positioned to understand how media technologies were evolving: in the 1960s he was one of the very first people to use televisual technologies as an artistic medium, earning him the title of “father” of video art. Born in Seoul in 1932, Paik studied composition while attending college in Tokyo; he eventually travelled to Germany, where he hoped to encounter the leading composers of the day. He met John Cage in 1958, and soon became involved with the avant-garde Fluxus group, led by Cage’s student George Maciunas.

Following the example of Cage’s oeuvre, many of Paik’s Fluxus works undermined accepted notions of musical composition or performance. This same irreverent spirit informed his use of television, to which he turned his attention in 1963 in his first one-man gallery show, “Exposition of Music—Electronic Television,” at the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, Germany. Here, Paik became the first artist to exhibit what would later become known as “video art” by scattering television sets across the floor of a room, thereby shifting our attention from the content on the screens to the sculptural forms of the sets.

The father of video art

Nam June Paik, Magnet TV, 1965, modified black-and-white television set and magnet (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York) © Nam June Paik Estate

Paik moved to New York in 1964, where he came into contact with the downtown art scene. In 1965, he began collaborating with cellist Charlotte Moorman, who would wear and perform Paik’s TV sculptures for many years; he also had a one-man show at the 57th Street Galeria Bonino, in which he exhibited modified or “prepared” television sets that upset the traditional TV-watching experience. One example is Magnet TV, in which an industrial magnet is placed on top of the TV set, distorting the broadcast image into abstract patterns of light.

According to an oft-cited story, on October 4th of that same year, Paik purchased the first commercially-available portable video system in America, the Sony Portapak, and immediately used it to record the arrival of Pope Paul VI at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Later that night, Paik showed the tape at the Café au Go Go in Greenwich Village, ushering in a new mode of video art based not on the subversion or distortion of television broadcasts, but on the possibilities of videotape. The evolution of these tendencies into a new movement was announced by a 1969 group show, “TV as a Creative Medium.” Held at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York, the show included one of Paik’s interactive TVs, and also premiered another one of his collaborations with Moorman.

TV as a creative medium

For Paik and other early adopters of video, this new artistic medium was well-suited to the speed of our increasingly electronic modern lives. It allowed artists to create moving images more quickly than recording on film (which required time for negatives to be developed), and unlike film, video could be edited in “real-time,” using devices that altered the video’s electronic signals. (Ever the pioneer, Paik created his own video synthesizer with engineer Shuya Abe in 1969.) Furthermore, because the image recorded by the video camera could be transmitted to and viewed almost instantaneously on a monitor, people could see themselves “live” on a TV screen, and even interact with their own TV image, in a process known as “feedback.” In the years to come, the participatory nature of TV would be redefined by two-way cable networks, while the advent of global satellite broadcasts made TV a medium of instant global communication.

Nam June Paik, TV Garden, 1974 (image shows 2000 version), video installation with color television sets and live plants (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York) © Nam June Paik Estate

As television continued to evolve from the late 1960s onward, Paik explored ways to disrupt it from both inside and outside of the institutional frameworks of galleries, museums, and emerging experimental TV labs. His major works from this period include TV Garden, a sculptural installation of TV sets scattered among live plants in a museum, and Good Morning, Mr. Orwell, a broadcast program that coordinated live feeds from around the world via satellite. In these and other projects, Paik’s goal was to reflect upon how we interact with technology and to imagine new ways of doing so. The many retrospectives of his work in recent decades, including one organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 2012, speak to the increasing relevance of his ideas for contemporary art.

Nam June Paik, V-yramid, 1982, video installation, color, sound, with forty television sets (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York) © Nam June Paik Estate

The nation electric

By the 1980s, Paik was building enormous, free-standing structures comprising dozens or even hundreds of TV screens, often organized into iconic shapes, as in the giant pyramid of V-yramid. For the German Pavilion at the 1993 Venice Biennale, Paik produced a series of works about the relationship between Eastern and Western cultures, framed through the lens of Marco Polo; along with Hans Haacke, another artist representing Germany, Paik was awarded the prestigious Golden Lion. One of the works, Electronic Superhighway, was a towering bank of TVs that simultaneously screened multiple video clips (including one of John Cage) from a wide variety of sources. Two years later, Paik revisited this work in Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, placing over 300 TV screens into the overall formation of a map of the United States outlined in colored neon lights (see image at the top of the page and the detail below). Roughly forty feet long and fifteen feet high, the work is a monumental record of the physical and also cultural contours of America: within each state, the screens display video clips that resonate with that state’s unique popular mythology. For example, Iowa (where each presidential election cycle begins) plays old news footage of various candidates, while Kansas presents the Wizard of Oz.

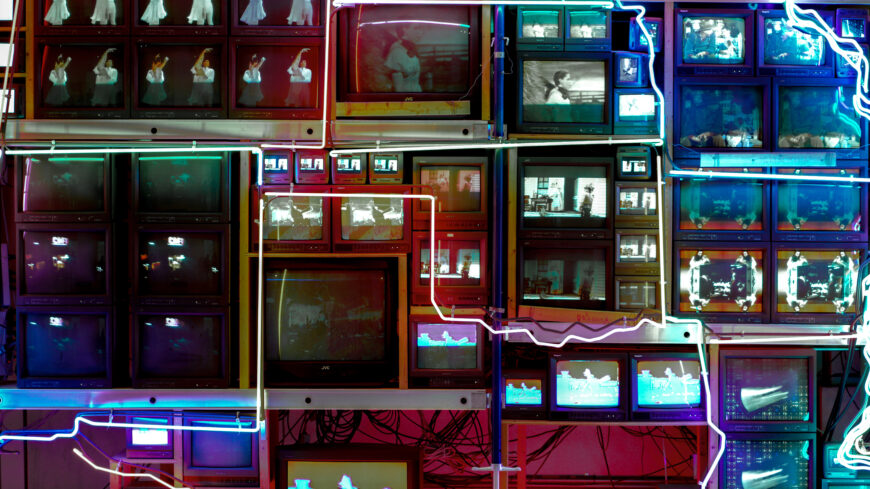

Oklahoma (detail), Nam June Paik, Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, 1995, fifty-one channel video installation (including one closed-circuit television feed), custom electronics, neon lighting, steel and wood; color, sound, approx. 15 x 40 x 4 feet (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) © Nam June Paik Estate

The states are firmly defined, but also linked, by the network of neon lights, which echoes the network of interstate “superhighways” that economically and culturally unified the continental U.S. in the 1950s. However, whereas the highways facilitated the transportation of people and goods from coast to coast, the neon lights suggest that what unifies us now is not so much transportation, but electronic communication. Thanks to the screens of televisions and of the home computers that became popular in the 1990s, as well as the cables of the internet (which transmit information as light), most of us can access the same information at anytime and from any place. Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, which has been housed at the Smithsonian American Art Museum since 2002, has therefore become an icon of America in the information age.

While Paik’s work is generally described as celebrating the fact that the “electronic superhighway” allows us to communicate with and understand each other across traditional boundaries, this particular work also can be read as posing some difficult questions about how that technology is impacting culture. For example, the physical scale of the work and number of simultaneous clips makes it difficult to absorb any details, resulting in what we now call “information overload,” and the visual tension between the static brightness of the neons and the dynamic brightness of the screens points to a similar tension between national and local frames of reference.