Use these images to support discussion and research on the Experiences of the U.S. Civil War. Build on the content already included in the essays and videos and refer to the discussion questions related to this theme to frame your inquiry.

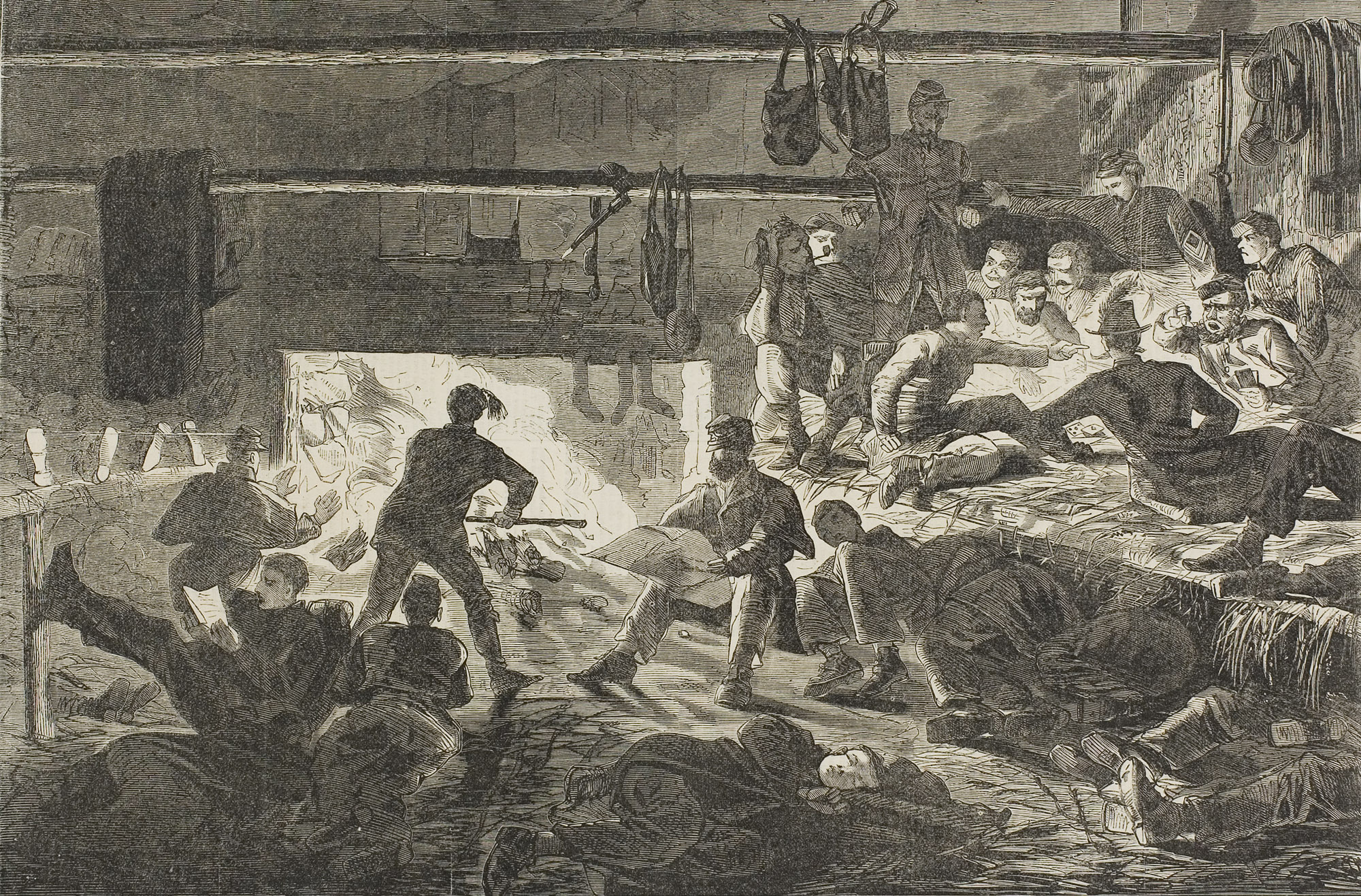

For the most part, Civil War battles did not take place in the winter. Published in Harper's Weekly on January 24, 1863, Winslow Homer’s portrayal of a large group of soldiers resting inside a hut shows them stoking the fire to keep warm and hanging up wet clothes to dry. Winslow Homer, Winter-Quarters in Camp—The Inside of a Hut, 1863, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly, January 24, 1863, 9 3/16 x 13 7/8 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

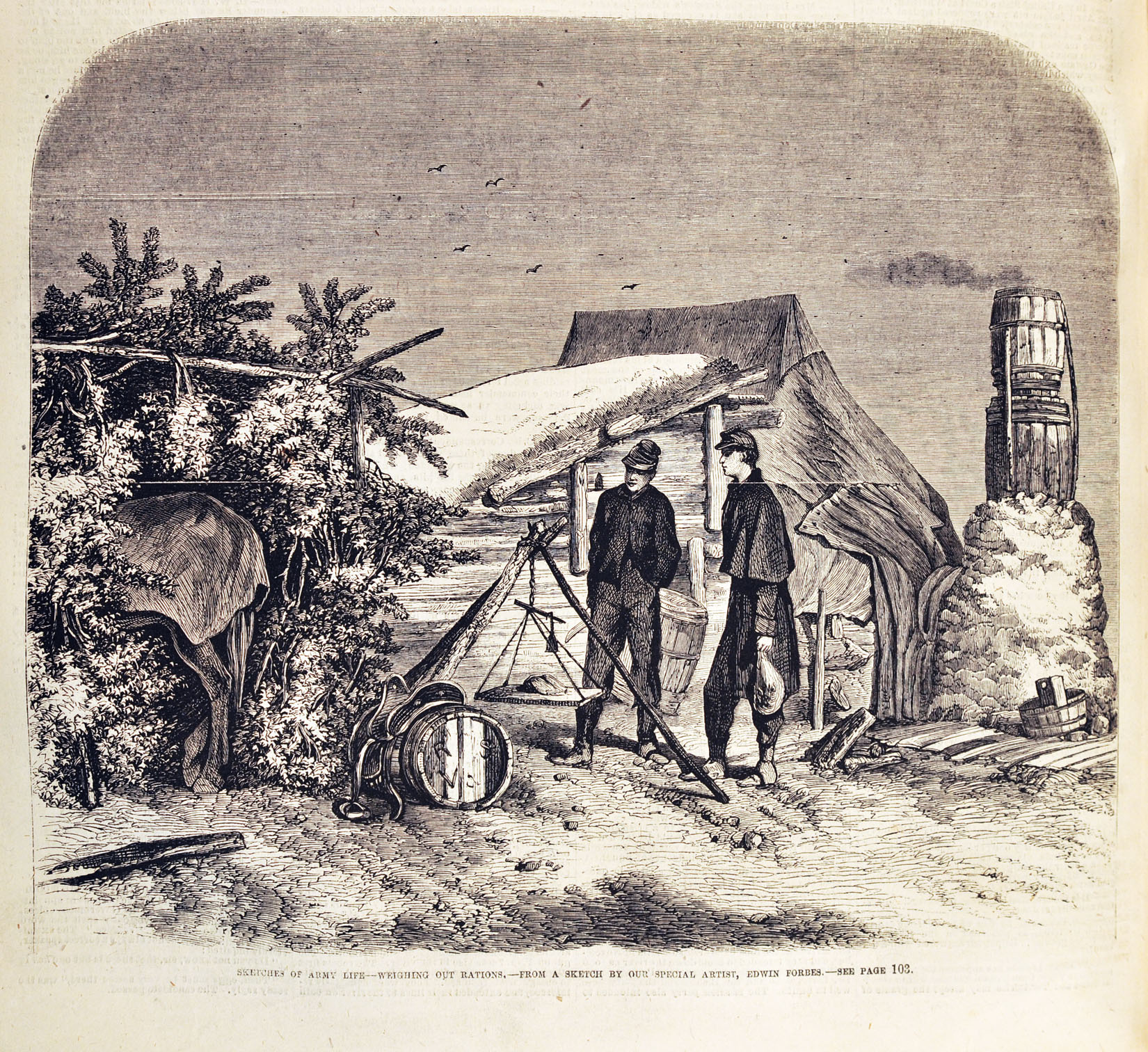

For the most part, Civil War battles did not take place in the winter. Published in Harper's Weekly on January 24, 1863, Winslow Homer’s portrayal of a large group of soldiers resting inside a hut shows them stoking the fire to keep warm and hanging up wet clothes to dry. Winslow Homer, Winter-Quarters in Camp—The Inside of a Hut, 1863, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly, January 24, 1863, 9 3/16 x 13 7/8 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) This image depicts a scene in the everyday life of Civil War soldiers and shows two men weighing supplies. The composition reveals slight changes made by the engraver who transferred Edwin Forbes' original drawing into a printed image for publication in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. An etching created by Forbes in 1876 is likely closer to his original drawing of the scene. Edwin Forbes, Weighing Out Rations, engraving from a field sketch, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, May 7, 1864, p. 100 (Chicago Public Library)

This image depicts a scene in the everyday life of Civil War soldiers and shows two men weighing supplies. The composition reveals slight changes made by the engraver who transferred Edwin Forbes' original drawing into a printed image for publication in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. An etching created by Forbes in 1876 is likely closer to his original drawing of the scene. Edwin Forbes, Weighing Out Rations, engraving from a field sketch, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, May 7, 1864, p. 100 (Chicago Public Library) It was very difficult for armies to fight in the winter due to the poor condition of roads, so soldiers frequently settled down into cabins and tents to ride out the coldest, wettest months. The commissary officer was in charge of supplying the army with all its food needs, and so was in charge of handing out rations. Here, two soldiers are weighing out a ration of war time foodstuffs. Artist Edwin Forbes based this etching on a drawing he created in 1864 during the war. Edwin Forbes, The Commissary's Quarters in Winter Camp, 1876, etching, 18 x 24 inches (Chicago Public Library)

It was very difficult for armies to fight in the winter due to the poor condition of roads, so soldiers frequently settled down into cabins and tents to ride out the coldest, wettest months. The commissary officer was in charge of supplying the army with all its food needs, and so was in charge of handing out rations. Here, two soldiers are weighing out a ration of war time foodstuffs. Artist Edwin Forbes based this etching on a drawing he created in 1864 during the war. Edwin Forbes, The Commissary's Quarters in Winter Camp, 1876, etching, 18 x 24 inches (Chicago Public Library) Soldiers in the Civil War commonly carried dippers (tin cups) like the ones seen here as part of their supplies. And, they enthusiastically picked fruit from orchards as they marched, eager for fresh and nutritious food. William Sydney Mount donated this painting to an auction held by the United States Sanitary Commission, a relief organization that supported the U.S. Army. William Sidney Mount, Fruit Piece: Apples on Tin Cups, 1864, oil on academy board, 6 1/2 x 9 1/16 inches (Terra Foundation for American Art)

Soldiers in the Civil War commonly carried dippers (tin cups) like the ones seen here as part of their supplies. And, they enthusiastically picked fruit from orchards as they marched, eager for fresh and nutritious food. William Sydney Mount donated this painting to an auction held by the United States Sanitary Commission, a relief organization that supported the U.S. Army. William Sidney Mount, Fruit Piece: Apples on Tin Cups, 1864, oil on academy board, 6 1/2 x 9 1/16 inches (Terra Foundation for American Art) The image documents the sparse physical comforts of army life, even on a holiday. Although an annual feast to give thanks had been celebrated on various days for more than a hundred years before this, it was Abraham Lincoln who established Thanksgiving on a fixed day beginning in 1863, one year after this image was made. Winslow Homer, Thanksgiving in Camp, 1862, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly, November 29, 1862, 9 3/16 x 13 3/4 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

The image documents the sparse physical comforts of army life, even on a holiday. Although an annual feast to give thanks had been celebrated on various days for more than a hundred years before this, it was Abraham Lincoln who established Thanksgiving on a fixed day beginning in 1863, one year after this image was made. Winslow Homer, Thanksgiving in Camp, 1862, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly, November 29, 1862, 9 3/16 x 13 3/4 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) Although men enlisted to fight in the Civil War, they spent the vast majority of their time in camp waiting for orders. Conrad Wise Chapman, an artist and Confederate soldier, depicted his experience in camp (using sketches he made on-site) in this painting. Conrad Wise Chapman, The Fifty-Ninth Virginia Infantry—Wise’s Brigade, c. 1867, oil on canvas, 20 1/8 x 33 7/8 inches (Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth)

Although men enlisted to fight in the Civil War, they spent the vast majority of their time in camp waiting for orders. Conrad Wise Chapman, an artist and Confederate soldier, depicted his experience in camp (using sketches he made on-site) in this painting. Conrad Wise Chapman, The Fifty-Ninth Virginia Infantry—Wise’s Brigade, c. 1867, oil on canvas, 20 1/8 x 33 7/8 inches (Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth) A special artist correspondent for Harper’s Weekly magazine, Winslow Homer sketched what he saw of soldiers’ lives while he was embedded with the U.S. Army on a few different occasions early in the war. Most of his sketches were mailed back to the magazine’s offices in New York City to be transformed by engravers into illustrations of the war for for circulation among northern audiences. During and after the war, Homer also turned his sketches into finished paintings, like this one. In paintings and prints, Homer largely depicted daily life in camp for soldiers rather than the more limited time they spent in battle. Winslow Homer, Rainy Day in Camp, 1871, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 91.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

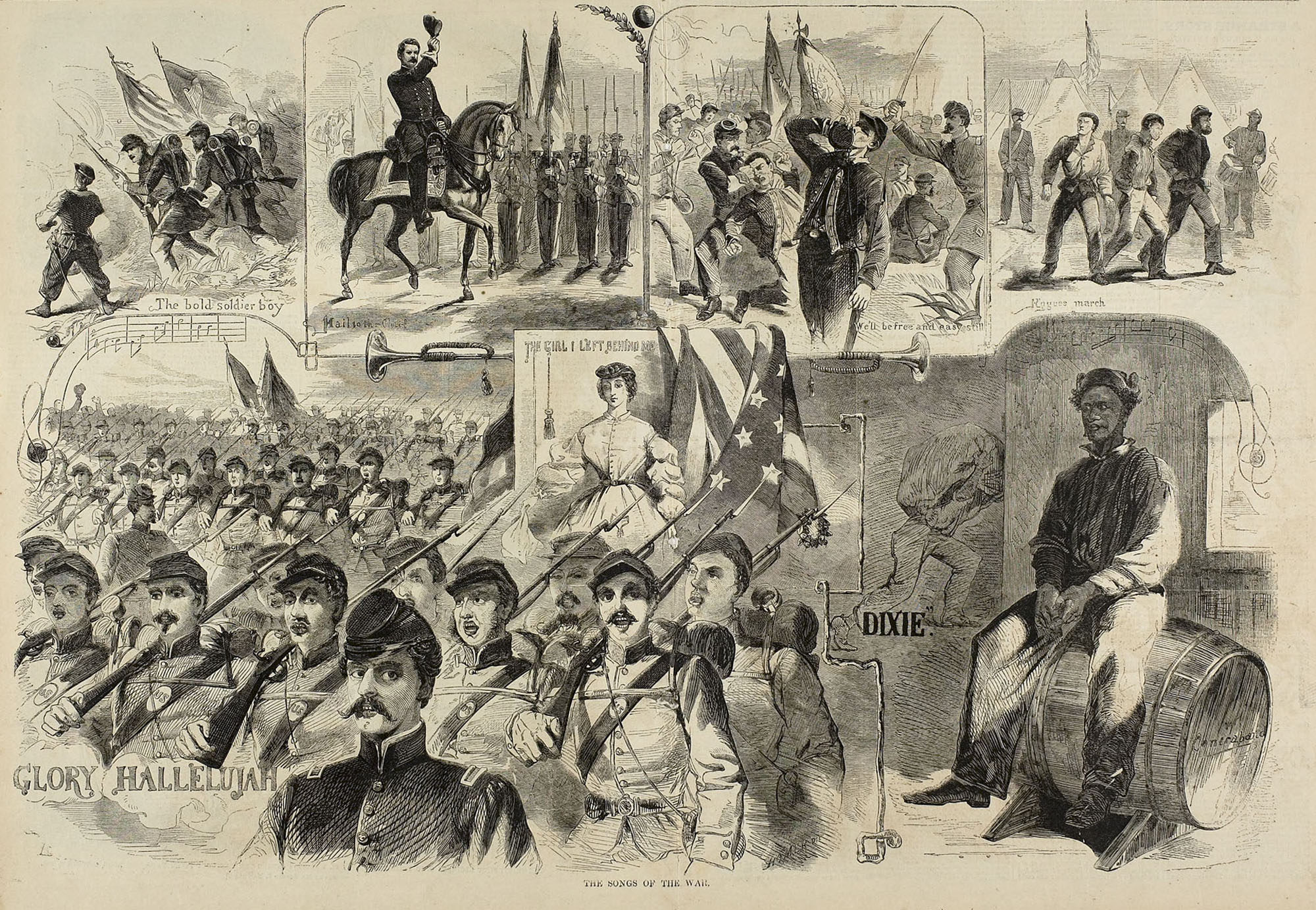

A special artist correspondent for Harper’s Weekly magazine, Winslow Homer sketched what he saw of soldiers’ lives while he was embedded with the U.S. Army on a few different occasions early in the war. Most of his sketches were mailed back to the magazine’s offices in New York City to be transformed by engravers into illustrations of the war for for circulation among northern audiences. During and after the war, Homer also turned his sketches into finished paintings, like this one. In paintings and prints, Homer largely depicted daily life in camp for soldiers rather than the more limited time they spent in battle. Winslow Homer, Rainy Day in Camp, 1871, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 91.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) During the U.S. Civil War, people frequently bought sheet music of their favorite songs, and in the military songs were sung and played to boost spirits during parades, on the march, and around campfires. The larger combat units had brass bands, and drummers on both sides delivered marching orders with the rhythms they played on their drums. In this picture, Winslow Homer used a variety of images the public would have recognized to illustrate seven of the more popular U.S. Army war songs. Winslow Homer, The Songs of the War, 1861, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly, November 23, 1861, 13 3/4 x 20 1/16 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

During the U.S. Civil War, people frequently bought sheet music of their favorite songs, and in the military songs were sung and played to boost spirits during parades, on the march, and around campfires. The larger combat units had brass bands, and drummers on both sides delivered marching orders with the rhythms they played on their drums. In this picture, Winslow Homer used a variety of images the public would have recognized to illustrate seven of the more popular U.S. Army war songs. Winslow Homer, The Songs of the War, 1861, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly, November 23, 1861, 13 3/4 x 20 1/16 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) The University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa was converted into a Confederate military school at the start of the U.S. Civil War. The Little Round House was essential to the alert system for the campus in the case of an attack, and cadets carried out sentry duty from the roof. It also housed munitions as well as the drum corps, comprised of two enslaved individuals who were rented to the university by their enslavers. The Little Round House, 1862, at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa

The University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa was converted into a Confederate military school at the start of the U.S. Civil War. The Little Round House was essential to the alert system for the campus in the case of an attack, and cadets carried out sentry duty from the roof. It also housed munitions as well as the drum corps, comprised of two enslaved individuals who were rented to the university by their enslavers. The Little Round House, 1862, at the University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa Both Black men and women contributed to the efforts of the U.S Army during the Civil War. While initially barred from enlisting, self-emancipated people nevertheless sought safe haven in army camps. These refugees provided labor as personal servants, cooks, launderers, stevedores, teamsters, and builders. Teamsters drove the wagons and cared for the pack animals that furnished the U.S. Army supply line. In 1862, Black men were legally allowed to enlist, most frequently serving in labor detail rather than combat. Winslow Homer, Army Teamsters, 1866, oil on canvas, 45.72 x 72.39 cm (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond)

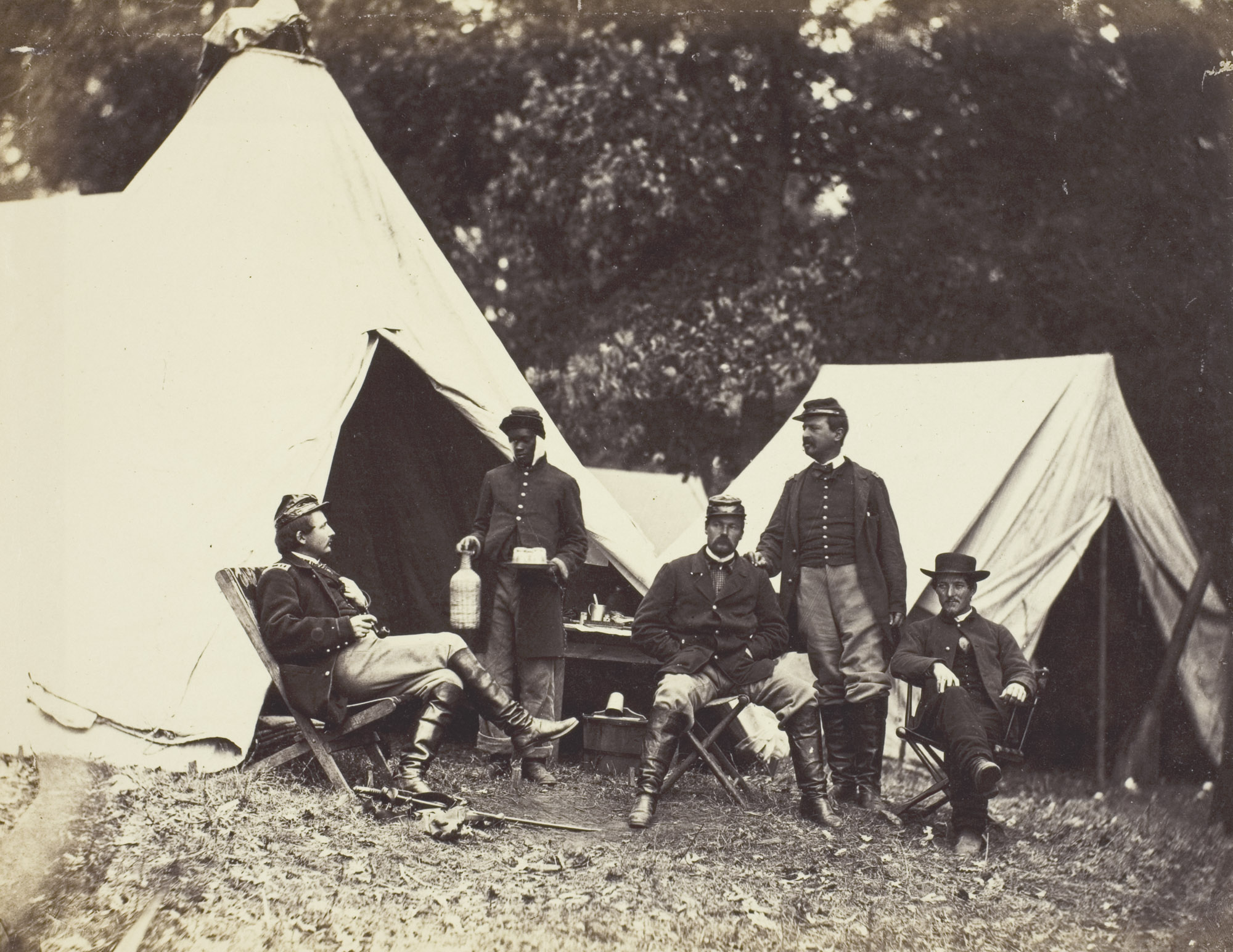

Both Black men and women contributed to the efforts of the U.S Army during the Civil War. While initially barred from enlisting, self-emancipated people nevertheless sought safe haven in army camps. These refugees provided labor as personal servants, cooks, launderers, stevedores, teamsters, and builders. Teamsters drove the wagons and cared for the pack animals that furnished the U.S. Army supply line. In 1862, Black men were legally allowed to enlist, most frequently serving in labor detail rather than combat. Winslow Homer, Army Teamsters, 1866, oil on canvas, 45.72 x 72.39 cm (Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond) This image portrays U.S. Army officers with their Black servant, John Henry. John Henry was a refugee (referred to at the time as "contraband"), one of many self-emancipated men and women who labored for the northern army, and in return received asylum from enslavement. They were often put to work as cooks, guides, and laborers. According to the photographer’s own caption for the image, the title comes from a question the captain would occasionally ask John Henry. Alexander Gardner, What Do I Want, John Henry?, 1862, albumen silver print, 6 13/16 x 8 13/16 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

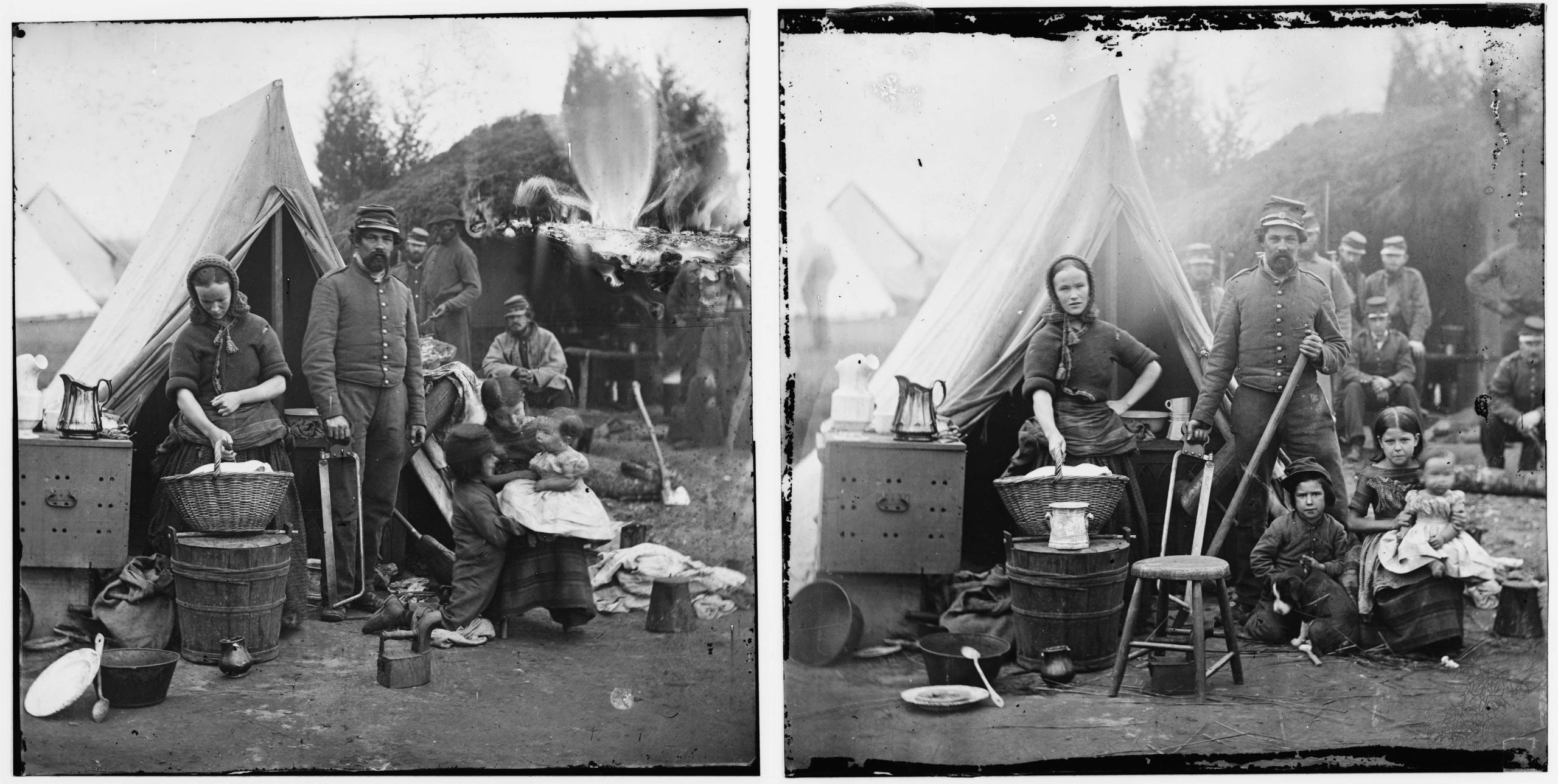

This image portrays U.S. Army officers with their Black servant, John Henry. John Henry was a refugee (referred to at the time as "contraband"), one of many self-emancipated men and women who labored for the northern army, and in return received asylum from enslavement. They were often put to work as cooks, guides, and laborers. According to the photographer’s own caption for the image, the title comes from a question the captain would occasionally ask John Henry. Alexander Gardner, What Do I Want, John Henry?, 1862, albumen silver print, 6 13/16 x 8 13/16 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) Civil War camps included men, women, and children. In some cases, entire families—who otherwise might have been destitute—followed their male breadwinner to camp, as in these two 1861 photographs of a Pennsylvania regiment camped outside of Washington, D.C., taken just moments apart. The photos also remind us that due to the cumbersome material and slow exposure time for wet-plate photography such images could not be spontaneous. Tent life of the 31st Penn. Inf. (later, 82d Penn. Inf.) at Queen's farm, vicinity of Fort Slocum, Washington, District of Columbia (detail), 1861, two wet collodion glass negatives (Library of Congress)

Civil War camps included men, women, and children. In some cases, entire families—who otherwise might have been destitute—followed their male breadwinner to camp, as in these two 1861 photographs of a Pennsylvania regiment camped outside of Washington, D.C., taken just moments apart. The photos also remind us that due to the cumbersome material and slow exposure time for wet-plate photography such images could not be spontaneous. Tent life of the 31st Penn. Inf. (later, 82d Penn. Inf.) at Queen's farm, vicinity of Fort Slocum, Washington, District of Columbia (detail), 1861, two wet collodion glass negatives (Library of Congress) In this print Winslow Homer emphasized the chaos of the conditions under which doctors had to work on the battlefield. A surgeon in the front left corner, his back to the audience, attends to a wounded soldier with the help of a comrade while the battle continues in the background. There is danger all around in this scene, as medical techniques used at the time could be as dangerous as the wounds or illnesses they were meant to treat. Winslow Homer, The Surgeon at Work at the Rear During an Engagement, 1862, wood engraving published by Harper’s Weekly, July 12, 1862, 9 3/16 x 13 13/16 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

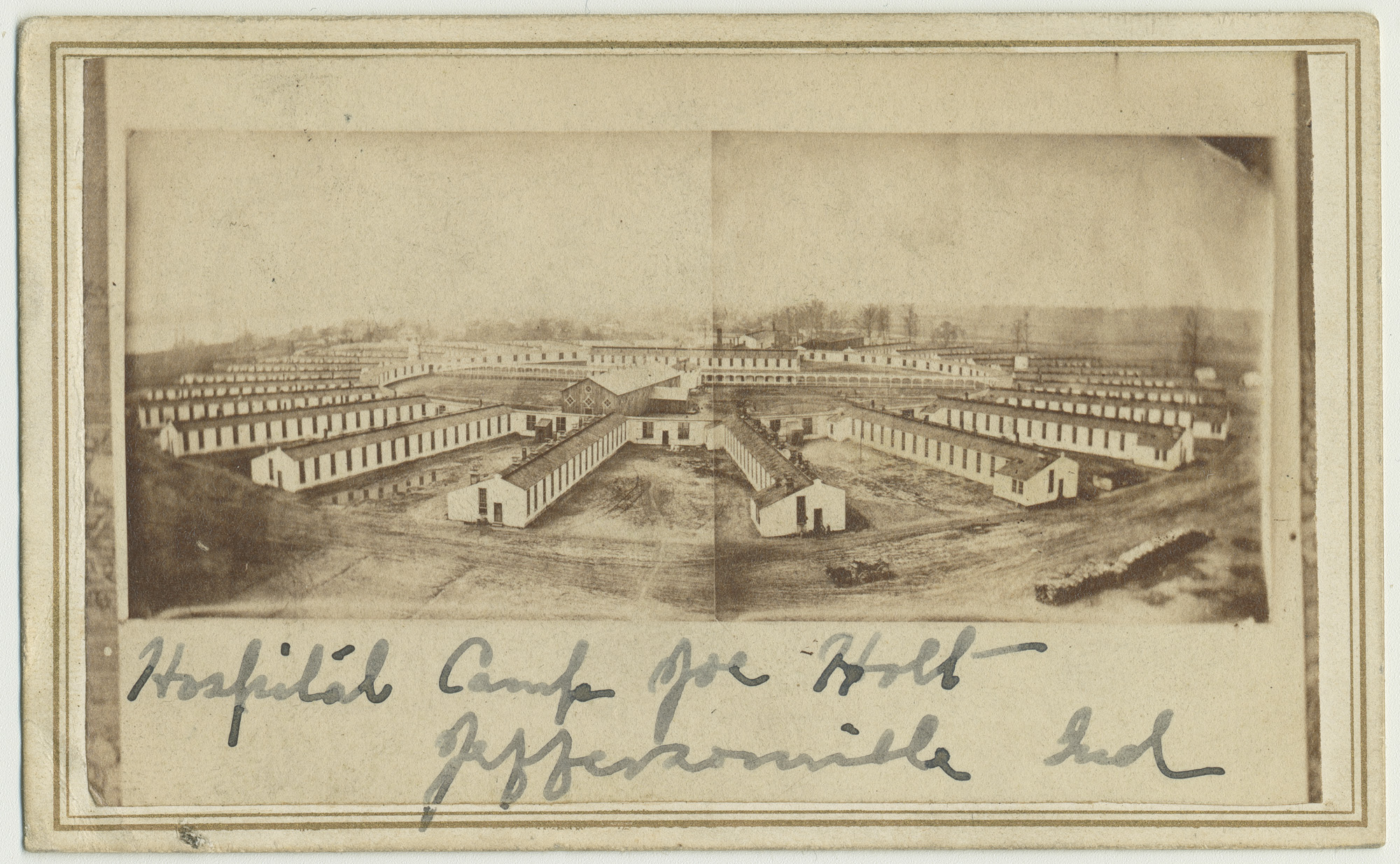

In this print Winslow Homer emphasized the chaos of the conditions under which doctors had to work on the battlefield. A surgeon in the front left corner, his back to the audience, attends to a wounded soldier with the help of a comrade while the battle continues in the background. There is danger all around in this scene, as medical techniques used at the time could be as dangerous as the wounds or illnesses they were meant to treat. Winslow Homer, The Surgeon at Work at the Rear During an Engagement, 1862, wood engraving published by Harper’s Weekly, July 12, 1862, 9 3/16 x 13 13/16 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) This photograph shows a hospital camp named Jefferson General near Jeffersonville, Indiana. The image is made of two separate photographs put together to form a panorama, or an overall view of the entire facility. Hospital Camp in Jeffersonville, Indiana, c. 1864–66, photograph, carte-de-visite, 2 1/2 x 4 inches (Chicago History Museum)

This photograph shows a hospital camp named Jefferson General near Jeffersonville, Indiana. The image is made of two separate photographs put together to form a panorama, or an overall view of the entire facility. Hospital Camp in Jeffersonville, Indiana, c. 1864–66, photograph, carte-de-visite, 2 1/2 x 4 inches (Chicago History Museum)![The United States General Hospital [at Georgetown, D.C., formerly the Union Hotel-Volunteer Nurses Attending the Sick and Wounded] The United States General Hospital [at Georgetown, D.C., formerly the Union Hotel-Volunteer Nurses Attending the Sick and Wounded], engraving from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, vol. 12, no. 294, July 6, 1861, p. 125 (Newberry Library)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/United-States-General-Hospital-at-Georgetown_Experiences.jpeg) The building used for the U.S. Army General Hospital was formerly the Union Hotel in Georgetown, D.C. It was common for large buildings, such as hotels, churches, schools, and large homes, to be converted into hospitals to help injured soldiers fighting nearby. Author Louisa May Alcott volunteered as a nurse at the U.S. Army General Hospital in 1862 but felt it was terribly run. The United States General Hospital at Georgetown, D.C., formerly the Union Hotel—Volunteer Nurses Attending the Sick and Wounded], engraving from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, July 6, 1861, p. 125 (Newberry Library)

The building used for the U.S. Army General Hospital was formerly the Union Hotel in Georgetown, D.C. It was common for large buildings, such as hotels, churches, schools, and large homes, to be converted into hospitals to help injured soldiers fighting nearby. Author Louisa May Alcott volunteered as a nurse at the U.S. Army General Hospital in 1862 but felt it was terribly run. The United States General Hospital at Georgetown, D.C., formerly the Union Hotel—Volunteer Nurses Attending the Sick and Wounded], engraving from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, July 6, 1861, p. 125 (Newberry Library) More than 5,000 women served as nurses in the Civil War, transforming the overwhelmingly male medical establishment. Many of these women worked with the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a relief agency dedicated to the support of sick and injured U.S. soldiers. Images like this one, created as a carte-de-visite, were sold or raffled at sanitary fairs in support of the agency's mission. Morse's Gallery of the Cumberland, Anna Bell Stubbs, Civil War nurse, caring for wounded soldiers at No. 1 Nashville Hospital, carte-de-visite, 1864 (Library of Congress)

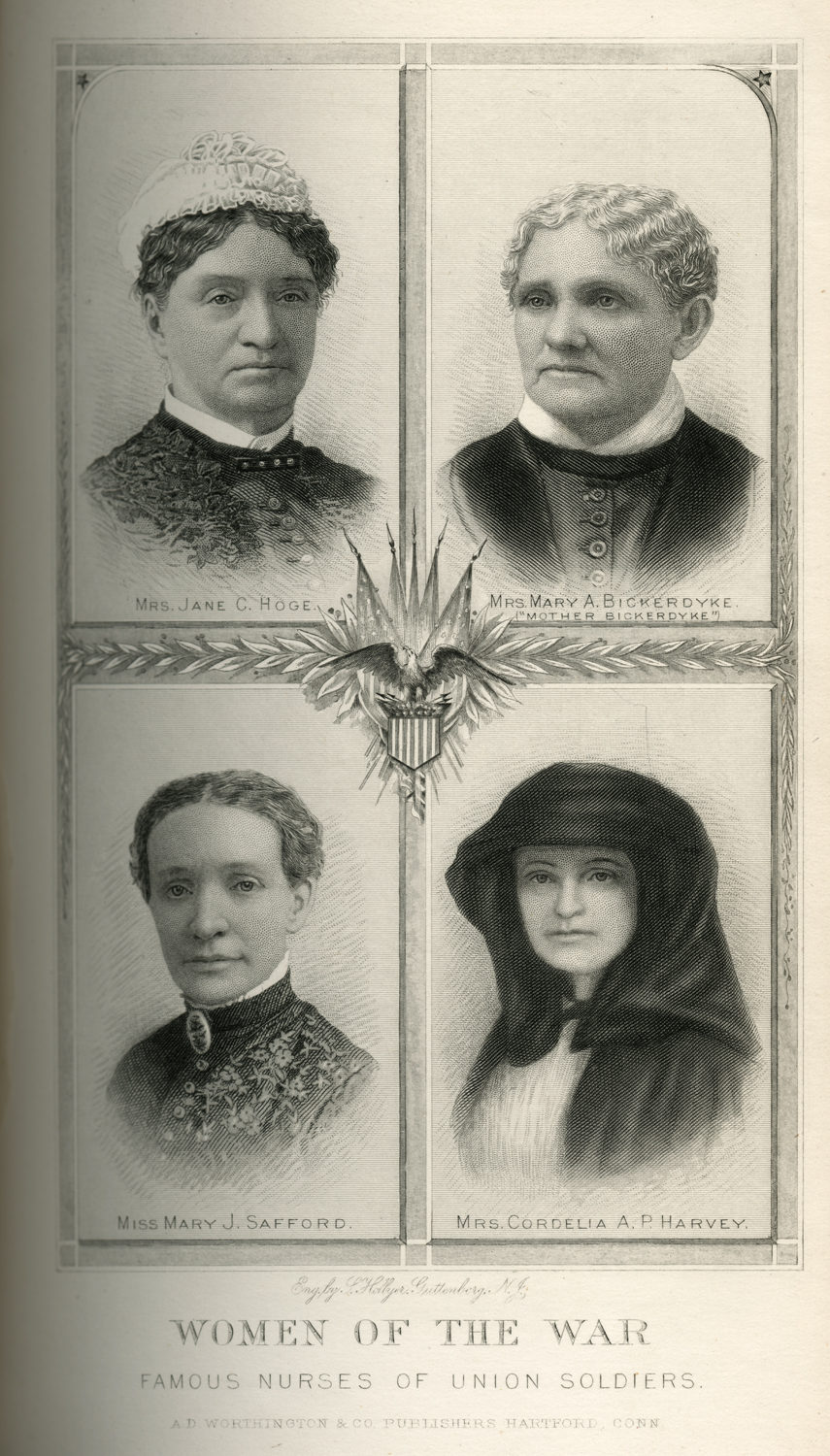

More than 5,000 women served as nurses in the Civil War, transforming the overwhelmingly male medical establishment. Many of these women worked with the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a relief agency dedicated to the support of sick and injured U.S. soldiers. Images like this one, created as a carte-de-visite, were sold or raffled at sanitary fairs in support of the agency's mission. Morse's Gallery of the Cumberland, Anna Bell Stubbs, Civil War nurse, caring for wounded soldiers at No. 1 Nashville Hospital, carte-de-visite, 1864 (Library of Congress) These portraits, probably based on photographs, show four female leaders in U.S. Civil War nursing. Mary Livermore related their stories in her book about her experience as a nurse and member of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. The women pictured include Jane C. Hoge, Mary A. Bickerdyke, Mary J. Safford, and Cordelia A.P. Harvey. Samuel Hollyer, Women of the War—Famous Nurses of Union Soldiers, 1889, engraving from photographs from Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War: A Woman's Narrative of Four Years Personal Experiences (Hartford, Connecticut: A.D. Worthington, 1889), p. 160 (Newberry Library)

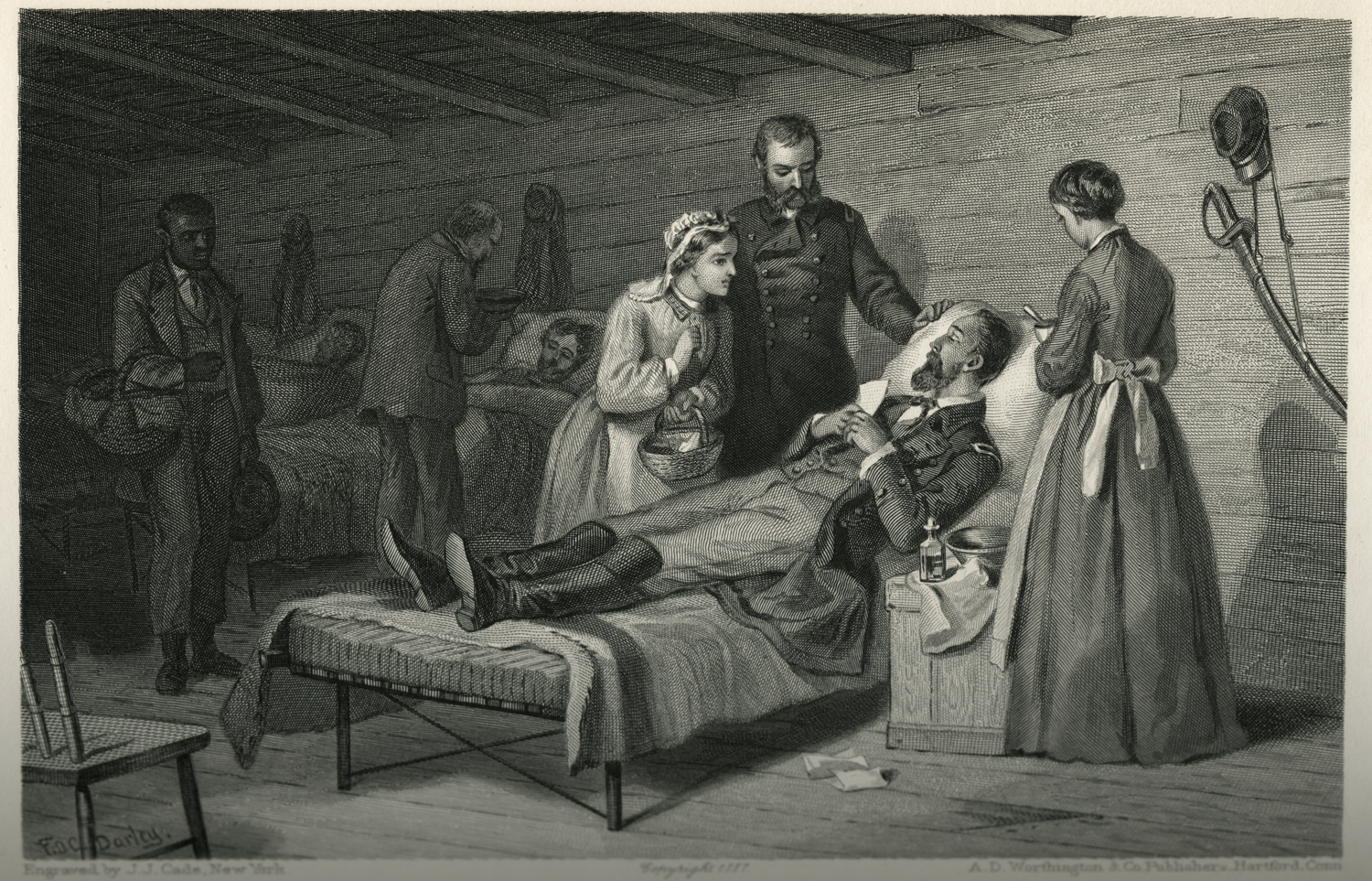

These portraits, probably based on photographs, show four female leaders in U.S. Civil War nursing. Mary Livermore related their stories in her book about her experience as a nurse and member of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. The women pictured include Jane C. Hoge, Mary A. Bickerdyke, Mary J. Safford, and Cordelia A.P. Harvey. Samuel Hollyer, Women of the War—Famous Nurses of Union Soldiers, 1889, engraving from photographs from Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War: A Woman's Narrative of Four Years Personal Experiences (Hartford, Connecticut: A.D. Worthington, 1889), p. 160 (Newberry Library) Nurse Mary Safford tends to a dying soldier who clings to a letter and photograph of loved ones at home. Also at the bedside are Mary Livermore of the U.S. Sanitary Commission and a U.S. Army officer. As an inspector for the Sanitary Commission, Livermore visited hospitals throughout Illinois and the nation, an experience which she recounts in her book My Story of the War. Felix Octavius Carr Darley was one of the most famous book illustrators of the 19th century. Felix Octavius Carr Darley and John J. Cade, The Dying Soldier—The Last Letter from Home, 1887, engraving from a sketch from Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War: A Woman's Narrative of Four Years Personal Experience (Hartford: A.D. Worthington and Company, 1889), p. 211 (Newberry Library)

Nurse Mary Safford tends to a dying soldier who clings to a letter and photograph of loved ones at home. Also at the bedside are Mary Livermore of the U.S. Sanitary Commission and a U.S. Army officer. As an inspector for the Sanitary Commission, Livermore visited hospitals throughout Illinois and the nation, an experience which she recounts in her book My Story of the War. Felix Octavius Carr Darley was one of the most famous book illustrators of the 19th century. Felix Octavius Carr Darley and John J. Cade, The Dying Soldier—The Last Letter from Home, 1887, engraving from a sketch from Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War: A Woman's Narrative of Four Years Personal Experience (Hartford: A.D. Worthington and Company, 1889), p. 211 (Newberry Library) Susie King Taylor, who was born into slavery in Georgia, and self-emancipated in 1862, supported the U.S. Army during the war by performing gun maintenance and working as a nurse and a teacher. She recorded her experiences in her memoir Reminiscences of My Life in Camp. Samuel Willard Bridgham, Susie King Taylor, 1880s, daguerreotype (Stephen Restelli, private collection)

Susie King Taylor, who was born into slavery in Georgia, and self-emancipated in 1862, supported the U.S. Army during the war by performing gun maintenance and working as a nurse and a teacher. She recorded her experiences in her memoir Reminiscences of My Life in Camp. Samuel Willard Bridgham, Susie King Taylor, 1880s, daguerreotype (Stephen Restelli, private collection) In this image, which was published with the title “The Influence of Women,” Winslow Homer depicts a variety of ways in which female involvement made a difference both in battles and at home during the U.S. Civil War. In the composition, a nun provides spiritual support to a wounded man, a woman helps a soldier write a letter, women work in encampments by cooking or washing clothes, and women at home knitted and sewed warm clothes for the troops. Homer only depicts white women, although Black and Indigenous women were also involved in and impacted by the war effort. Winslow Homer, Our Women in the War, 1864, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly September 6, 1864, 13 5/8 x 20 3/4 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

In this image, which was published with the title “The Influence of Women,” Winslow Homer depicts a variety of ways in which female involvement made a difference both in battles and at home during the U.S. Civil War. In the composition, a nun provides spiritual support to a wounded man, a woman helps a soldier write a letter, women work in encampments by cooking or washing clothes, and women at home knitted and sewed warm clothes for the troops. Homer only depicts white women, although Black and Indigenous women were also involved in and impacted by the war effort. Winslow Homer, Our Women in the War, 1864, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly September 6, 1864, 13 5/8 x 20 3/4 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) The U.S. Army depended greatly on Black noncombatant military laborers, both men and women, who often performed the most difficult tasks associated with keeping the army running. This rare photograph, believed to depict a Black washerwoman who was with the U.S. Army in Richmond, hints at the investment self-emancipated people felt toward U.S. victory: gazing straight into the camera, the woman wears an American flag on her dress, next to a brass “U.S.” pin. Washerwoman for the Union army in Richmond, Virginia, c. 1862–65, hand-colored ambrotype, 9.5 cm x 8.2 cm x 1.6 cm (National Museum of American History)

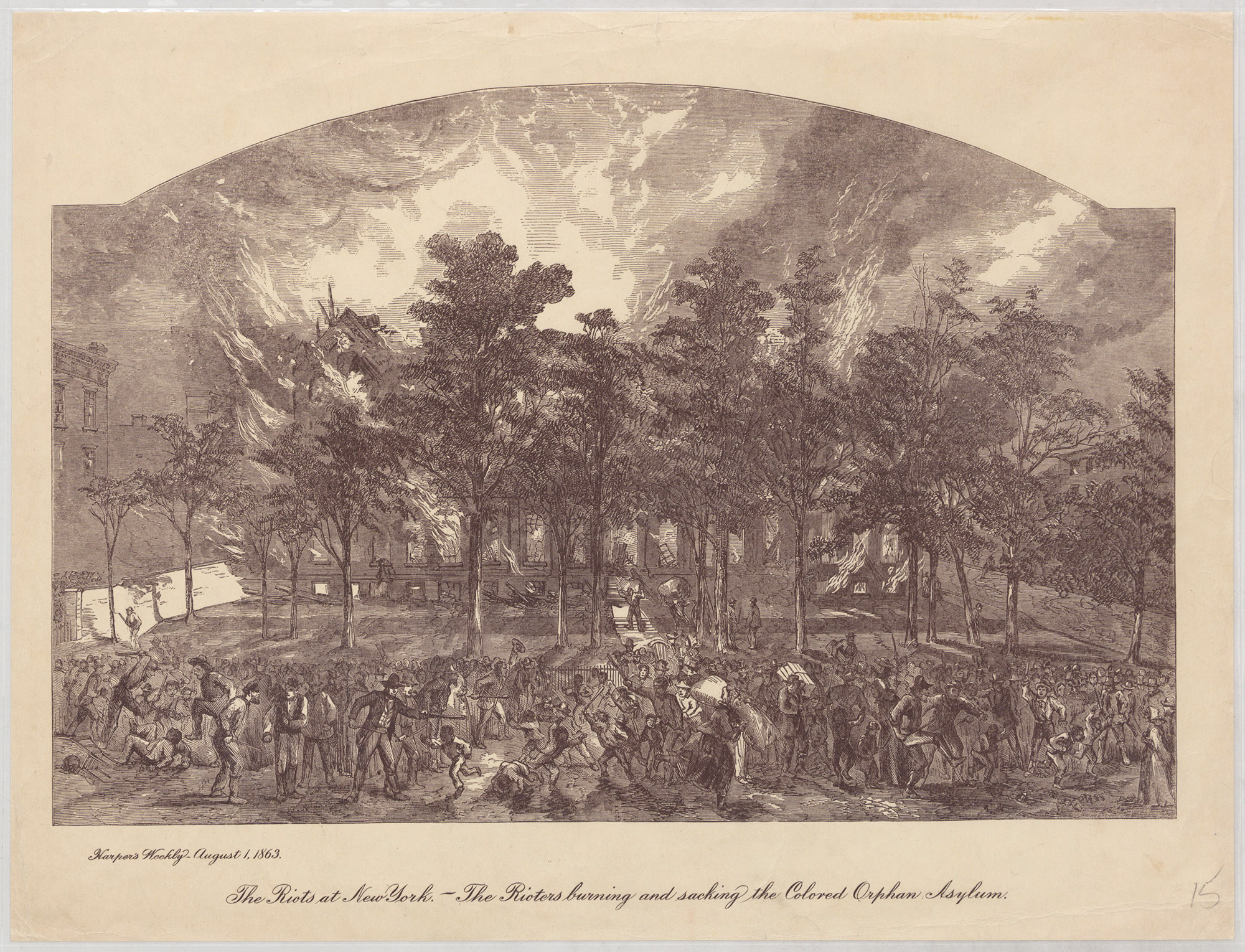

The U.S. Army depended greatly on Black noncombatant military laborers, both men and women, who often performed the most difficult tasks associated with keeping the army running. This rare photograph, believed to depict a Black washerwoman who was with the U.S. Army in Richmond, hints at the investment self-emancipated people felt toward U.S. victory: gazing straight into the camera, the woman wears an American flag on her dress, next to a brass “U.S.” pin. Washerwoman for the Union army in Richmond, Virginia, c. 1862–65, hand-colored ambrotype, 9.5 cm x 8.2 cm x 1.6 cm (National Museum of American History)![The Sanitary Fair at Brooklyn [The Academy of Music, Montague Street, with the Bridge Across to New England Kitchen], engraving from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, March 5, 1864, p. 380 (Newberry Library) The Sanitary Fair at Brooklyn [The Academy of Music, Montague Street, with the Bridge Across to New England Kitchen], engraving from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, March 5, 1864, p. 380 (Newberry Library)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Sanitary-Fair-at-Brooklyn_Homefront.jpeg) Regional Sanitary Fairs were organized by northern women to raise funds for the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a government organization established to aid wounded soldiers and keep soldiers on the battlefronts healthy. The Brooklyn Sanitary Fair, held in 1864, raised $400,000. This image shows the part of the fair called the “New England Kitchen," a type of living history exhibit where colonial-era recipes were prepared for visitors to try out. "The Sanitary Fair at Brooklyn—The New England Kitchen." [The Academy of Music, Montague Street, with the Bridge Across to New England Kitchen], Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, March 5, 1864, p. 380, engraving (Newberry Library)

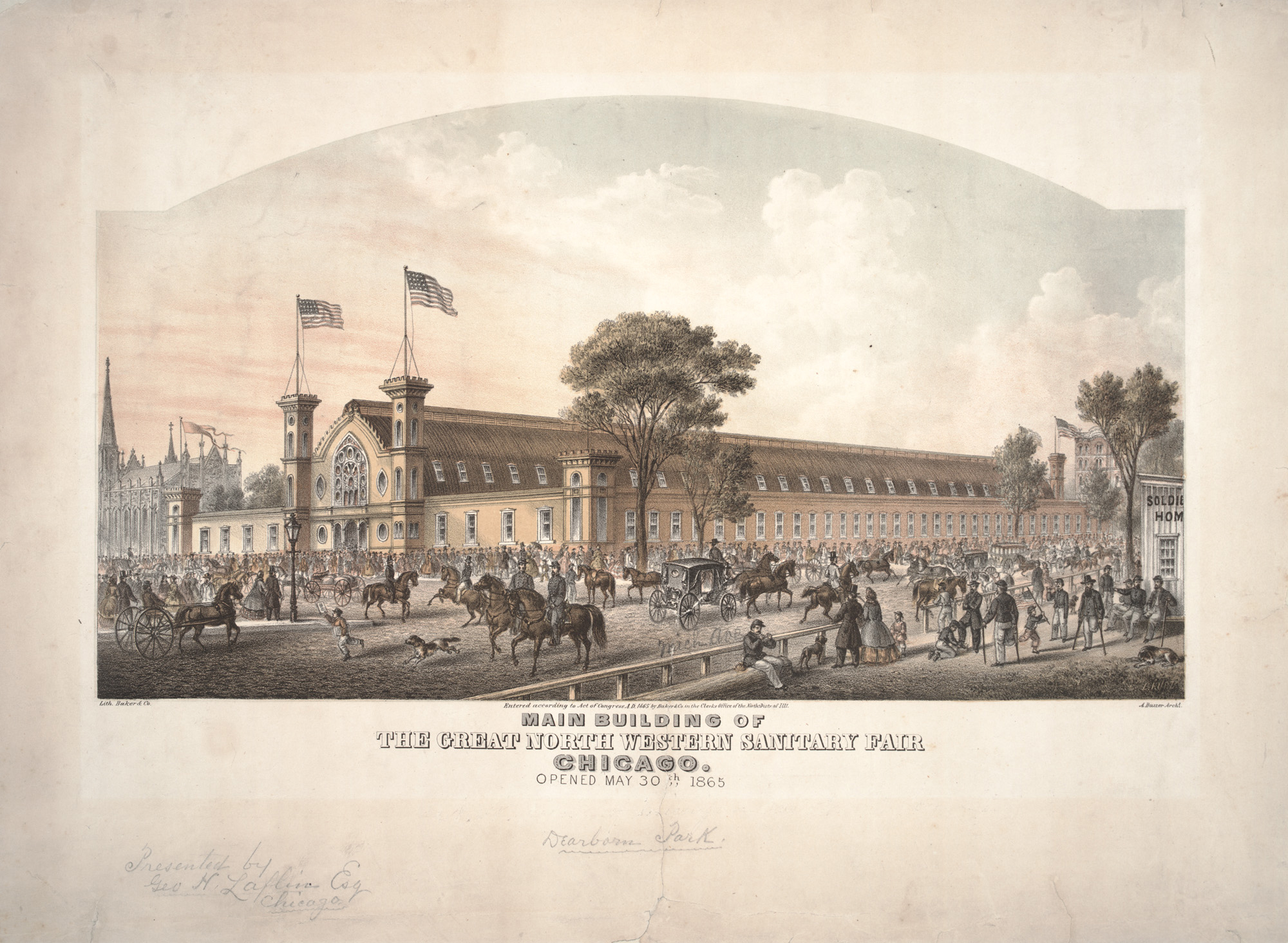

Regional Sanitary Fairs were organized by northern women to raise funds for the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a government organization established to aid wounded soldiers and keep soldiers on the battlefronts healthy. The Brooklyn Sanitary Fair, held in 1864, raised $400,000. This image shows the part of the fair called the “New England Kitchen," a type of living history exhibit where colonial-era recipes were prepared for visitors to try out. "The Sanitary Fair at Brooklyn—The New England Kitchen." [The Academy of Music, Montague Street, with the Bridge Across to New England Kitchen], Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, March 5, 1864, p. 380, engraving (Newberry Library) The Great Northwestern Sanitary Fair of 1865 was the second fair held in Chicago by the United States Sanitary Commission. It raised over $200,000 to support soldiers at the front as well as veterans who had been wounded. Many of the men, women, and children who could not fight in the war served the U.S. Army by working for sanitary fairs like this one. Louis Kurz, Main Building of the Great North Western Sanitary Fair, Chicago, 1865, lithograph, 16 x 21 5/8 inches (Chicago History Museum)

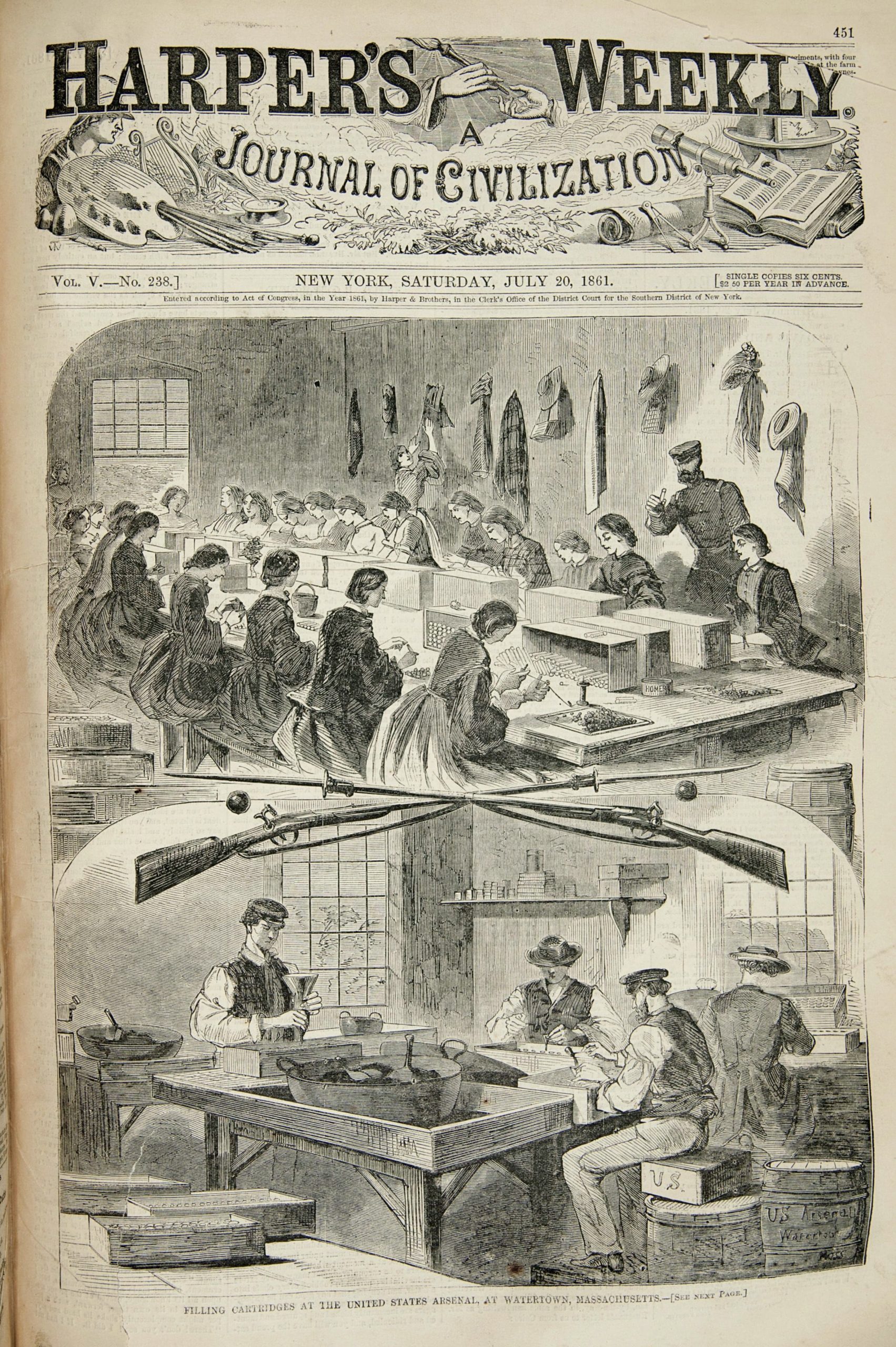

The Great Northwestern Sanitary Fair of 1865 was the second fair held in Chicago by the United States Sanitary Commission. It raised over $200,000 to support soldiers at the front as well as veterans who had been wounded. Many of the men, women, and children who could not fight in the war served the U.S. Army by working for sanitary fairs like this one. Louis Kurz, Main Building of the Great North Western Sanitary Fair, Chicago, 1865, lithograph, 16 x 21 5/8 inches (Chicago History Museum) The need for labor during the war challenged notions of the proper role for women in society. For example, Harper’s Weekly marveled at the novelty of white women working to fill cartridges at an arsenal in Watertown, Massachusetts in 1861. In reality, however, working at an arsenal was a dangerous job and the women who did so were often young immigrants. Winslow Homer, Filling Cartridges at the United States Arsenal at Watertown, Massachusetts, published by Harper's Weekly, July 20, 1861, wood engraving on paper, 10 15/16 x 9 1/4 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

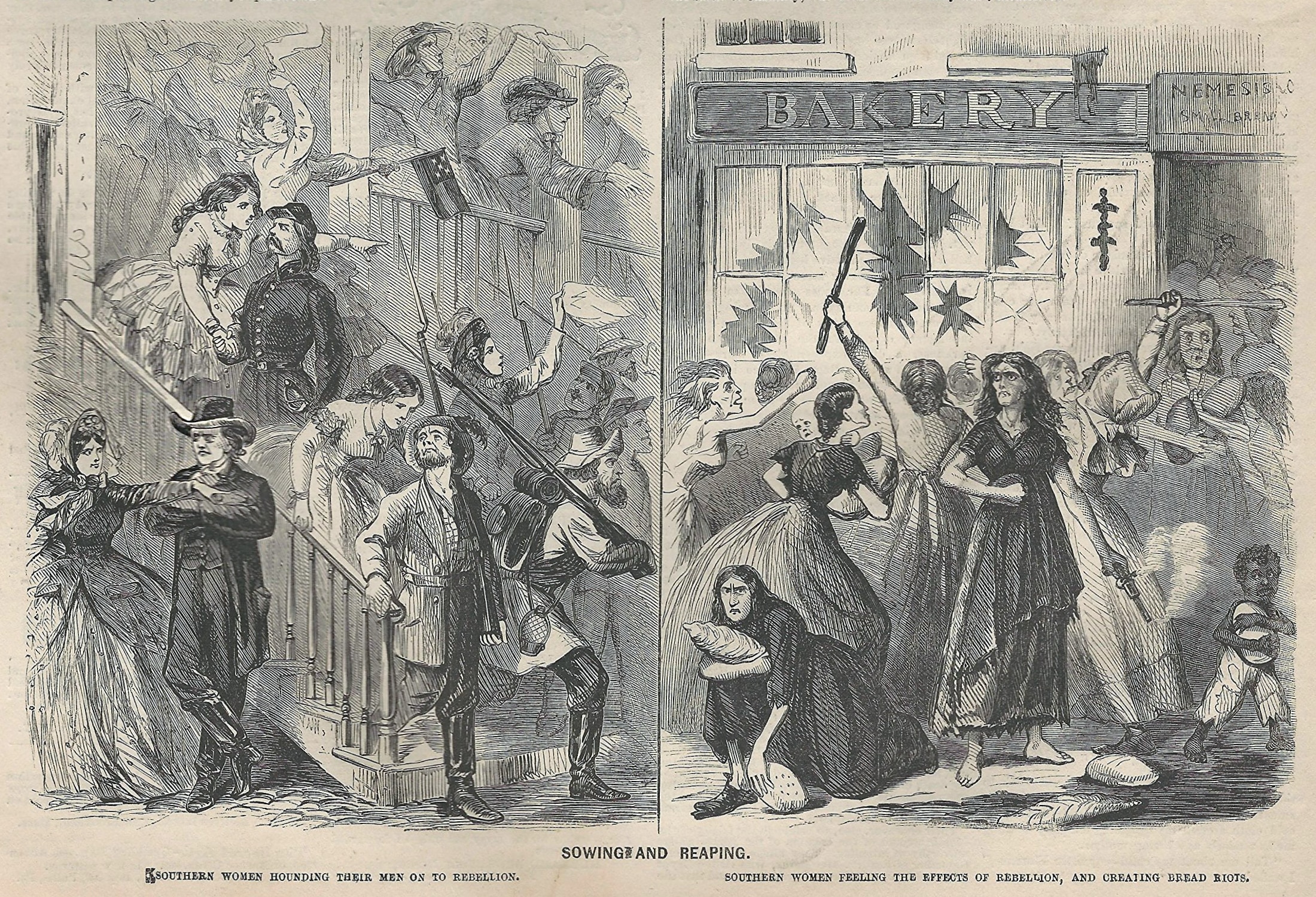

The need for labor during the war challenged notions of the proper role for women in society. For example, Harper’s Weekly marveled at the novelty of white women working to fill cartridges at an arsenal in Watertown, Massachusetts in 1861. In reality, however, working at an arsenal was a dangerous job and the women who did so were often young immigrants. Winslow Homer, Filling Cartridges at the United States Arsenal at Watertown, Massachusetts, published by Harper's Weekly, July 20, 1861, wood engraving on paper, 10 15/16 x 9 1/4 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) The need for labor during the war challenged notions of the proper role for women in society. Among other tasks, women took on jobs in arsenals, a dangerous task previously considered only acceptable for men. In 1864, twenty-one white, mostly Irish immigrant women died in an explosion at the Washington, D.C. arsenal. Fifteen of the women were buried under a monument at the Congressional Cemetery erected just one year later. Left: Lot Flannery, Grief, 1865, marble monument to the victims of the 1864 explosion at the Washington, D.C. arsenal, Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C. (photo: Allen C. Browne); right: Detail of the statue's inscriptions (photo: Library of Congress)

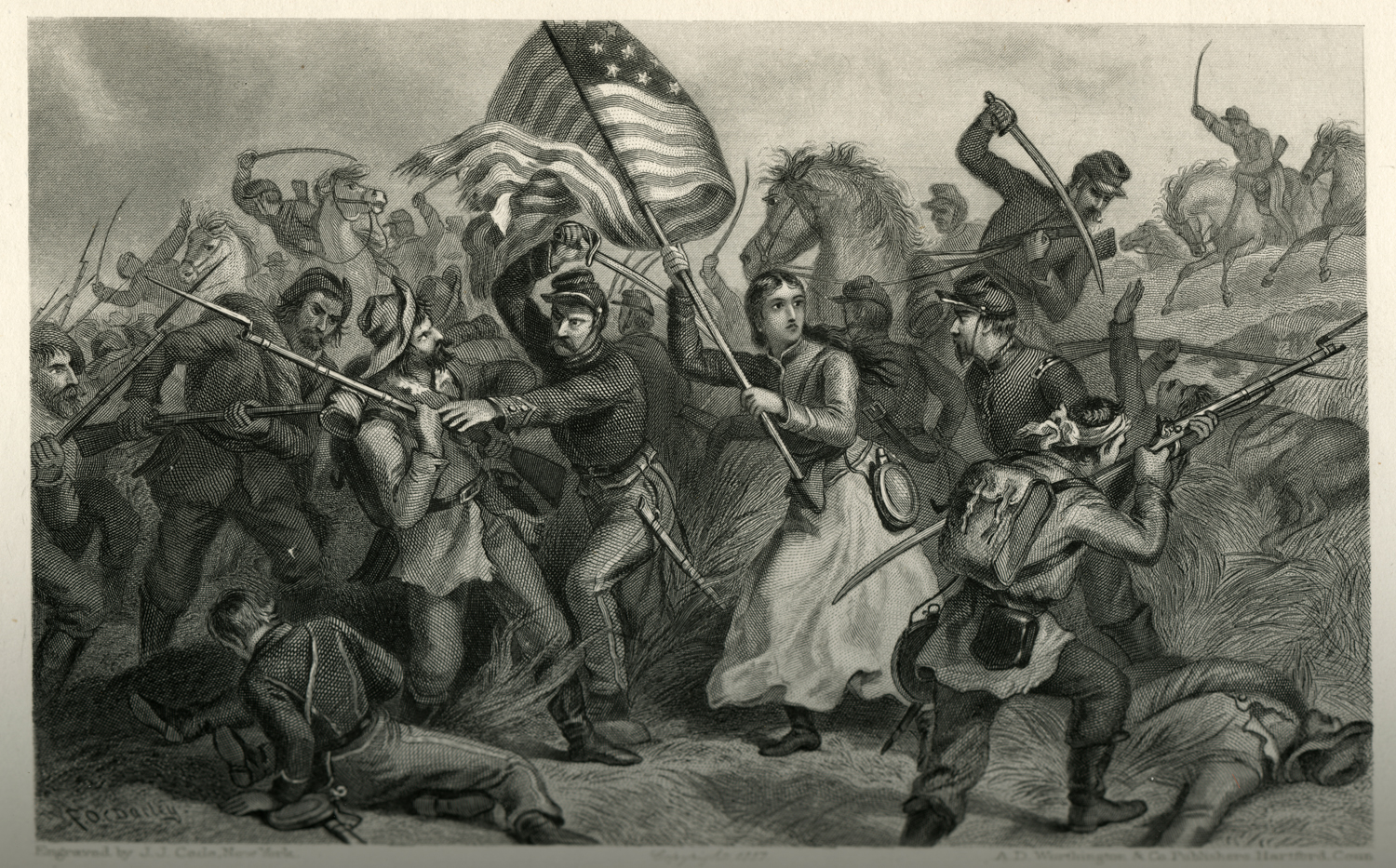

The need for labor during the war challenged notions of the proper role for women in society. Among other tasks, women took on jobs in arsenals, a dangerous task previously considered only acceptable for men. In 1864, twenty-one white, mostly Irish immigrant women died in an explosion at the Washington, D.C. arsenal. Fifteen of the women were buried under a monument at the Congressional Cemetery erected just one year later. Left: Lot Flannery, Grief, 1865, marble monument to the victims of the 1864 explosion at the Washington, D.C. arsenal, Congressional Cemetery, Washington, D.C. (photo: Allen C. Browne); right: Detail of the statue's inscriptions (photo: Library of Congress) In this drawing, Bridget Devens, also known as “Michigan Bridget,” courageously carrying the U.S. Army flag amidst a violent battle. Devens and her husband joined the First Michigan Calvary, an army regiment. Though she spent most of the time behind the front lines tending the wounded, author Mary Livermore claimed that "sometimes when a soldier fell, she [Devens] took his place, fighting in his stead with unquailing [determined] courage." While a relatively rare occurrence, other women also accompanied their husbands’ regiments, and officers in winter camp frequently brought their wives, and sometimes their children, to stay with them for periods of time. Felix Octavius Carr Darley and John J. Cade, A Woman in Battle: Michigan Bridget Carrying the Flag, 1887, engraving from a sketch from Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War: A Woman's Narrative of Four Years Personal Experience (Hartford: A.D. Worthington and Company, 1889), p. 117 (Newberry Library)

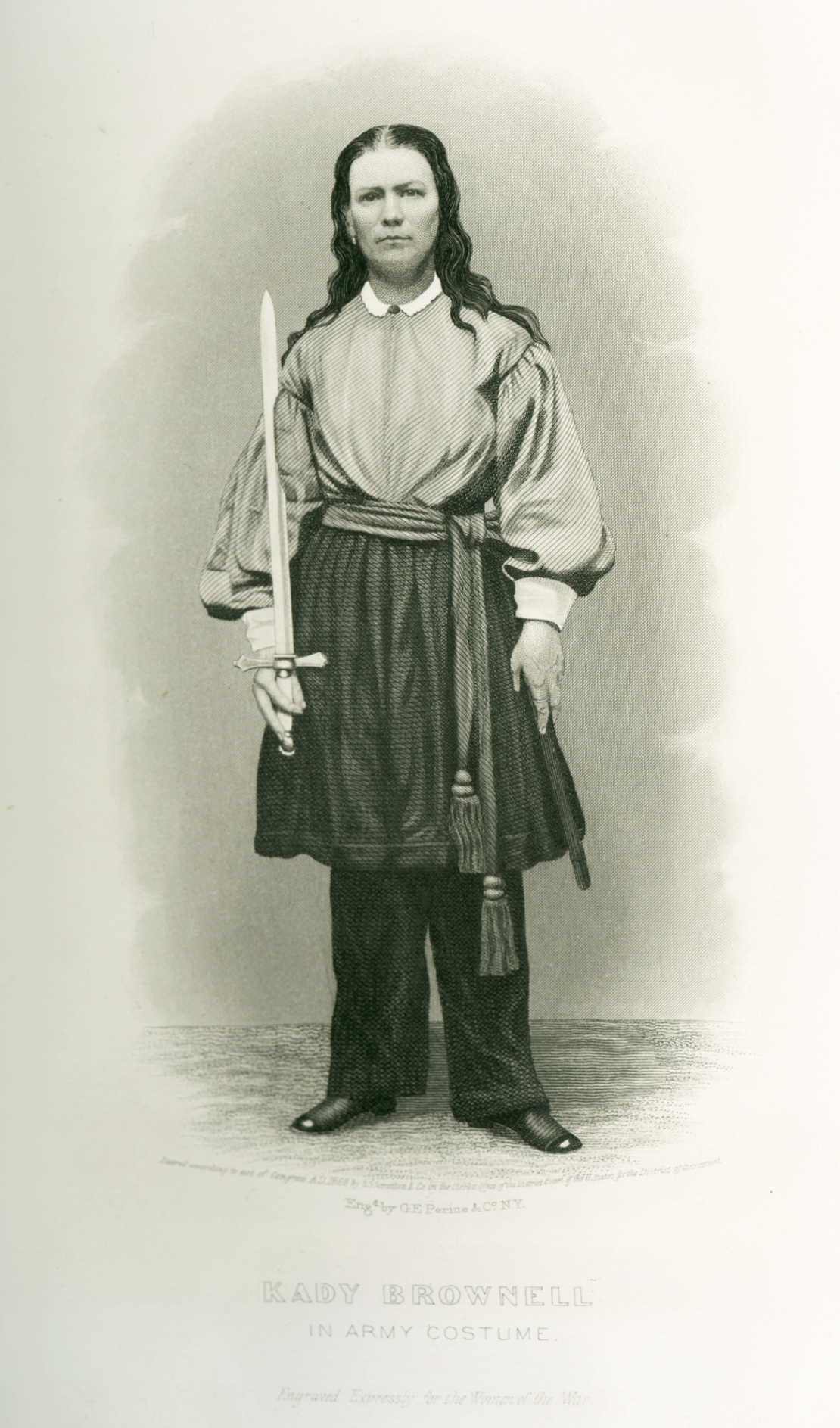

In this drawing, Bridget Devens, also known as “Michigan Bridget,” courageously carrying the U.S. Army flag amidst a violent battle. Devens and her husband joined the First Michigan Calvary, an army regiment. Though she spent most of the time behind the front lines tending the wounded, author Mary Livermore claimed that "sometimes when a soldier fell, she [Devens] took his place, fighting in his stead with unquailing [determined] courage." While a relatively rare occurrence, other women also accompanied their husbands’ regiments, and officers in winter camp frequently brought their wives, and sometimes their children, to stay with them for periods of time. Felix Octavius Carr Darley and John J. Cade, A Woman in Battle: Michigan Bridget Carrying the Flag, 1887, engraving from a sketch from Mary A. Livermore, My Story of the War: A Woman's Narrative of Four Years Personal Experience (Hartford: A.D. Worthington and Company, 1889), p. 117 (Newberry Library) Kady Brownell was one of about 250 women to fight in the Civil War. Some women wanted to serve as soldiers and dressed as men to gain access to the army—but not Brownell. Instead, she fought openly as a woman alongside her husband in the Fifth Rhode Island Infantry. This portrait made after the war shows her holding a ceremonial sword, but during the war she was in charge of carrying the flag into battle. Kady Brownell in Army Costume, 1866, engraving from Frank Moore, Women of the War; Their Heroism and Self Sacrifice, (Hartford, Connecticut: S.S. Scranton, 1866), p. 55 (Newberry Library)

Kady Brownell was one of about 250 women to fight in the Civil War. Some women wanted to serve as soldiers and dressed as men to gain access to the army—but not Brownell. Instead, she fought openly as a woman alongside her husband in the Fifth Rhode Island Infantry. This portrait made after the war shows her holding a ceremonial sword, but during the war she was in charge of carrying the flag into battle. Kady Brownell in Army Costume, 1866, engraving from Frank Moore, Women of the War; Their Heroism and Self Sacrifice, (Hartford, Connecticut: S.S. Scranton, 1866), p. 55 (Newberry Library) This type of image is called a “combination print,” where two different photographic negatives are pieced together. Here, General Blair was added on the far right after the original photograph was made. Combination prints were very popular in the 1860s. This group portrait of the U.S. Army General William Tecumseh Sherman and his generals was made in May 1865 during the Grand Review of the Armies, a military parade in Washington, D.C. following the end of the war. George N. Barnard, Sherman and His Generals, 1865, albumen print from collodion negative, 10 1/8 x 14 1/8 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

This type of image is called a “combination print,” where two different photographic negatives are pieced together. Here, General Blair was added on the far right after the original photograph was made. Combination prints were very popular in the 1860s. This group portrait of the U.S. Army General William Tecumseh Sherman and his generals was made in May 1865 during the Grand Review of the Armies, a military parade in Washington, D.C. following the end of the war. George N. Barnard, Sherman and His Generals, 1865, albumen print from collodion negative, 10 1/8 x 14 1/8 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) J. Russell Jones, a Grant supporter from Galena, Illinois, commissioned Chicago artist John Antrobus to paint Grant’s likeness—the first artist to draw him from life. Antrobus traveled to Chattanooga, Tennessee, where Grant was headquartered and made sketches of the general. Antrobus then made two paintings: this three-quarter-length view and a full-length portrait. John Antrobus, General Ulysses S. Grant, 1863, oil on canvas, 50 x 40.5 inches (Chicago Public Library)

J. Russell Jones, a Grant supporter from Galena, Illinois, commissioned Chicago artist John Antrobus to paint Grant’s likeness—the first artist to draw him from life. Antrobus traveled to Chattanooga, Tennessee, where Grant was headquartered and made sketches of the general. Antrobus then made two paintings: this three-quarter-length view and a full-length portrait. John Antrobus, General Ulysses S. Grant, 1863, oil on canvas, 50 x 40.5 inches (Chicago Public Library) Originally a Democratic Party politician in Illinois, John Logan shifted his loyalties and lent his support for the U.S. Army once the war got underway. He played leading roles in the battles of Fort Donelson, Atlanta, and the Carolinas Campaign. After the war, he joined the Republican Party and served as a representative, senator, and vice presidential candidate, as well as head of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). H. K. Saunders, General John A. Logan, 1911, oil on canvas, 65 x 45 inches (Chicago Public Library)

Originally a Democratic Party politician in Illinois, John Logan shifted his loyalties and lent his support for the U.S. Army once the war got underway. He played leading roles in the battles of Fort Donelson, Atlanta, and the Carolinas Campaign. After the war, he joined the Republican Party and served as a representative, senator, and vice presidential candidate, as well as head of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). H. K. Saunders, General John A. Logan, 1911, oil on canvas, 65 x 45 inches (Chicago Public Library) Photographs provide the largest source of visual evidence about the people who lived through the Civil War, including untold numbers of portraits of soldiers. Enlisted men rushed to have their photographs taken in uniform, representing their military prowess and social standing. Left: Moore Bro's. Photographic Gallery, Unidentified Union sailor in uniform in front of painted backdrop showing walkway and trees, c. 1861–65, albumen print on card (Library of Congress); right: Israel & Co., First Lieutenant Patrick Boyce of Co. F, 8th Regular Army Infantry Regiment in uniform with sword, c. 1861–65 (Library of Congress)

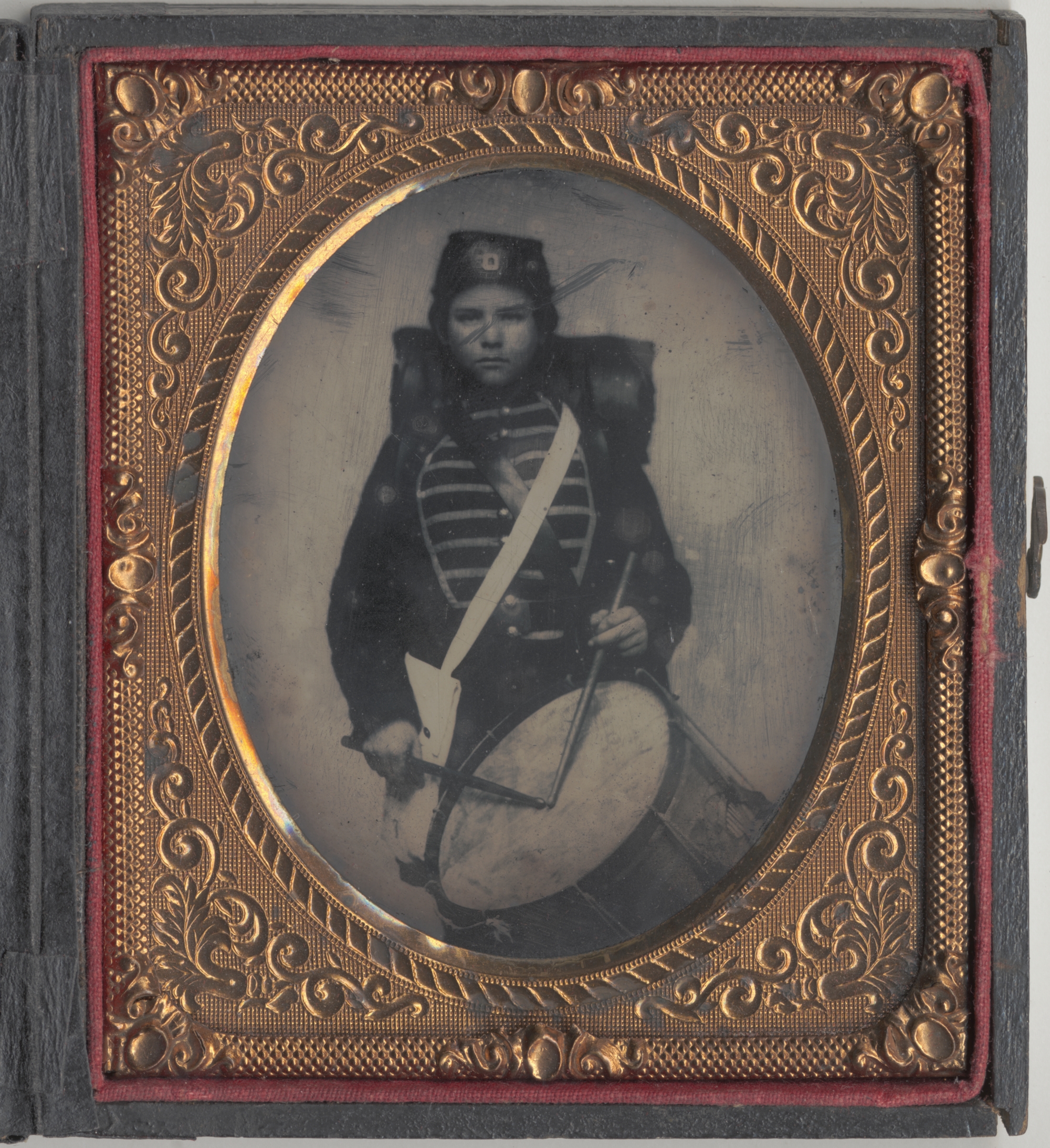

Photographs provide the largest source of visual evidence about the people who lived through the Civil War, including untold numbers of portraits of soldiers. Enlisted men rushed to have their photographs taken in uniform, representing their military prowess and social standing. Left: Moore Bro's. Photographic Gallery, Unidentified Union sailor in uniform in front of painted backdrop showing walkway and trees, c. 1861–65, albumen print on card (Library of Congress); right: Israel & Co., First Lieutenant Patrick Boyce of Co. F, 8th Regular Army Infantry Regiment in uniform with sword, c. 1861–65 (Library of Congress) John F. P. Robie, featured wearing his uniform and carrying a snare drum, was only thirteen years old when he joined a New Hampshire infantry regiment. In addition to helping soldiers march in rhythm, drummer boys like Robie used various drum calls to send messages and signals to the troops. Some were wounded in the course of these duties. Portrait of John F. P. Robie, c. 1861, ambrotype in brass mat and paperboard case (Chicago History Museum)

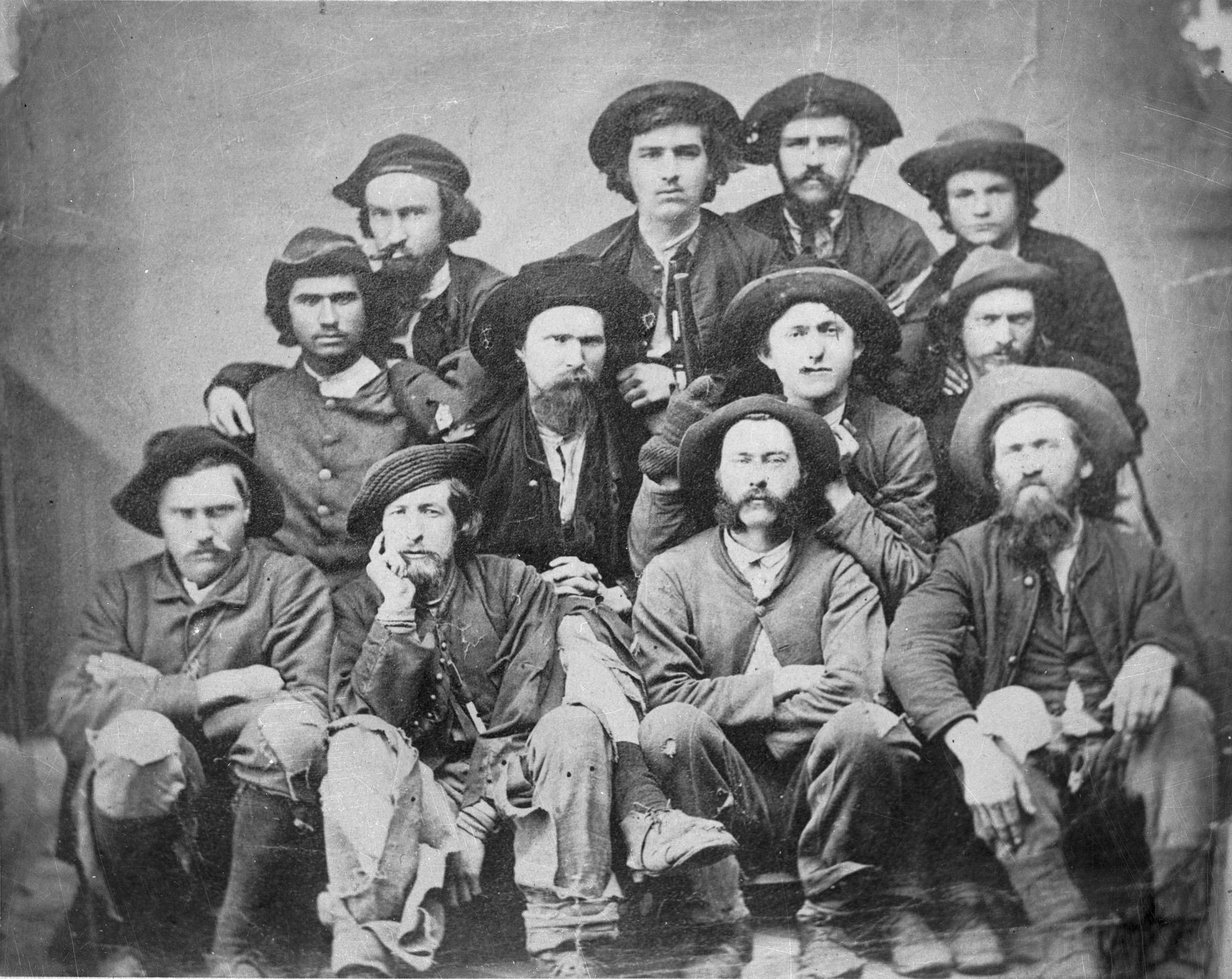

John F. P. Robie, featured wearing his uniform and carrying a snare drum, was only thirteen years old when he joined a New Hampshire infantry regiment. In addition to helping soldiers march in rhythm, drummer boys like Robie used various drum calls to send messages and signals to the troops. Some were wounded in the course of these duties. Portrait of John F. P. Robie, c. 1861, ambrotype in brass mat and paperboard case (Chicago History Museum) These soldiers belonged to a volunteer drill team organized in 1859 by Elmer Ellsworth of Chicago. He copied their name and colorful uniforms after the French Zouaves of the Crimean War. Here we see the troupe in Utica, New York, during a tour of eastern cities in 1860. During the Civil War, some of the Chicago Zouaves joined the U.S. Army, serving with the Nineteenth Illinois Infantry and wearing the uniforms that artist J. Graff documented in this painting. J. Graff, The Chicago Zouaves Cadet Drill Team at Utica, c. 1860, oil on panel, 34 x 51 1/4 inches (Chicago History Museum)

These soldiers belonged to a volunteer drill team organized in 1859 by Elmer Ellsworth of Chicago. He copied their name and colorful uniforms after the French Zouaves of the Crimean War. Here we see the troupe in Utica, New York, during a tour of eastern cities in 1860. During the Civil War, some of the Chicago Zouaves joined the U.S. Army, serving with the Nineteenth Illinois Infantry and wearing the uniforms that artist J. Graff documented in this painting. J. Graff, The Chicago Zouaves Cadet Drill Team at Utica, c. 1860, oil on panel, 34 x 51 1/4 inches (Chicago History Museum) Bandolier bags such as this one were worn by high-ranking Indigenous men across their bodies during ceremonies or in battle to carry ammunition. A female Indigenous artist likely made this bag, which was worn into battle by its owner, likely a Delaware soldier who was fighting as part of the U.S.-allied Indian Home Guard (three Indigenous regiments recruited primarily from the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole nations). Bandolier bag, likely Delaware, wool, glass beads, cotton, fringe c. 1860 (The American Civil War Museum, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Bandolier bags such as this one were worn by high-ranking Indigenous men across their bodies during ceremonies or in battle to carry ammunition. A female Indigenous artist likely made this bag, which was worn into battle by its owner, likely a Delaware soldier who was fighting as part of the U.S.-allied Indian Home Guard (three Indigenous regiments recruited primarily from the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole nations). Bandolier bag, likely Delaware, wool, glass beads, cotton, fringe c. 1860 (The American Civil War Museum, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) Bandolier bags such as this one were worn by high-ranking Indigenous men across their bodies during ceremonies or in battle to carry ammunition. A female Indigenous artist likely made this bag, which was worn into battle by its owner, likely a Delaware soldier who was fighting as part of the U.S.-allied Indian Home Guard (three Indigenous regiments recruited primarily from the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole nations). Bandolier bag, likely Delaware, wool, glass beads, cotton, fringe c. 1860 (The American Civil War Museum, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Bandolier bags such as this one were worn by high-ranking Indigenous men across their bodies during ceremonies or in battle to carry ammunition. A female Indigenous artist likely made this bag, which was worn into battle by its owner, likely a Delaware soldier who was fighting as part of the U.S.-allied Indian Home Guard (three Indigenous regiments recruited primarily from the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole nations). Bandolier bag, likely Delaware, wool, glass beads, cotton, fringe c. 1860 (The American Civil War Museum, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) The sign Balldwin holds up with his hand reads “Co. G 56,” which means he belonged to Company G, 56th United States Colored Infantry. The three stripes on his left sleeve tell us that he was a sergeant. Tintypes were very popular for portraits during the war. While more expensive than unframed carte-de-visites, they allowed the sitter to be given a print only minutes after the photograph was taken. Tintype of Black Union Soldier, J. L. Balldwin, c. 1863 (Chicago History Museum)

The sign Balldwin holds up with his hand reads “Co. G 56,” which means he belonged to Company G, 56th United States Colored Infantry. The three stripes on his left sleeve tell us that he was a sergeant. Tintypes were very popular for portraits during the war. While more expensive than unframed carte-de-visites, they allowed the sitter to be given a print only minutes after the photograph was taken. Tintype of Black Union Soldier, J. L. Balldwin, c. 1863 (Chicago History Museum) For Black soldiers, sitting for a photographic portrait was not just a record of their bravery in volunteering to serve, but also a claim to citizenship, which was constantly called into question. The Black soldier pictured here holds a pistol across his chest and his belt buckle proclaims his status as a “US” soldier. The photograph was encased in a frame with numerous symbols of U.S. citizenship and national belonging. Hand-colored tintype with cover glass of an unknown Black U.S. soldier, in black thermoplastic case with brass hinges and red velvet liner, c. 1861–65 (Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

For Black soldiers, sitting for a photographic portrait was not just a record of their bravery in volunteering to serve, but also a claim to citizenship, which was constantly called into question. The Black soldier pictured here holds a pistol across his chest and his belt buckle proclaims his status as a “US” soldier. The photograph was encased in a frame with numerous symbols of U.S. citizenship and national belonging. Hand-colored tintype with cover glass of an unknown Black U.S. soldier, in black thermoplastic case with brass hinges and red velvet liner, c. 1861–65 (Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture) A simplified version of the Great Seal of the United States was reproduced on the uniform buttons of U.S. soldiers: a bald eagle with its wings spread behind a shield, grasping an olive branch in one set of talons and arrows in the other. Stamped brass uniform button with American eagle, c. 1861–65, (Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

A simplified version of the Great Seal of the United States was reproduced on the uniform buttons of U.S. soldiers: a bald eagle with its wings spread behind a shield, grasping an olive branch in one set of talons and arrows in the other. Stamped brass uniform button with American eagle, c. 1861–65, (Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture) A scrimshaw is a carved piece of bone, teeth, or ivory, often made by whalers or sailors. This piece, made by an unknown artist near the North Carolina coast, dates to sometime after spring 1863, when the U.S. Army officially began to enlist Black soldiers. It depicts a Black soldier in uniform. Scrimshaw with portrait of Black soldier, c. 1863, inscription on whale-tooth, 5 x 2 1/2 inches (Chicago History Museum)

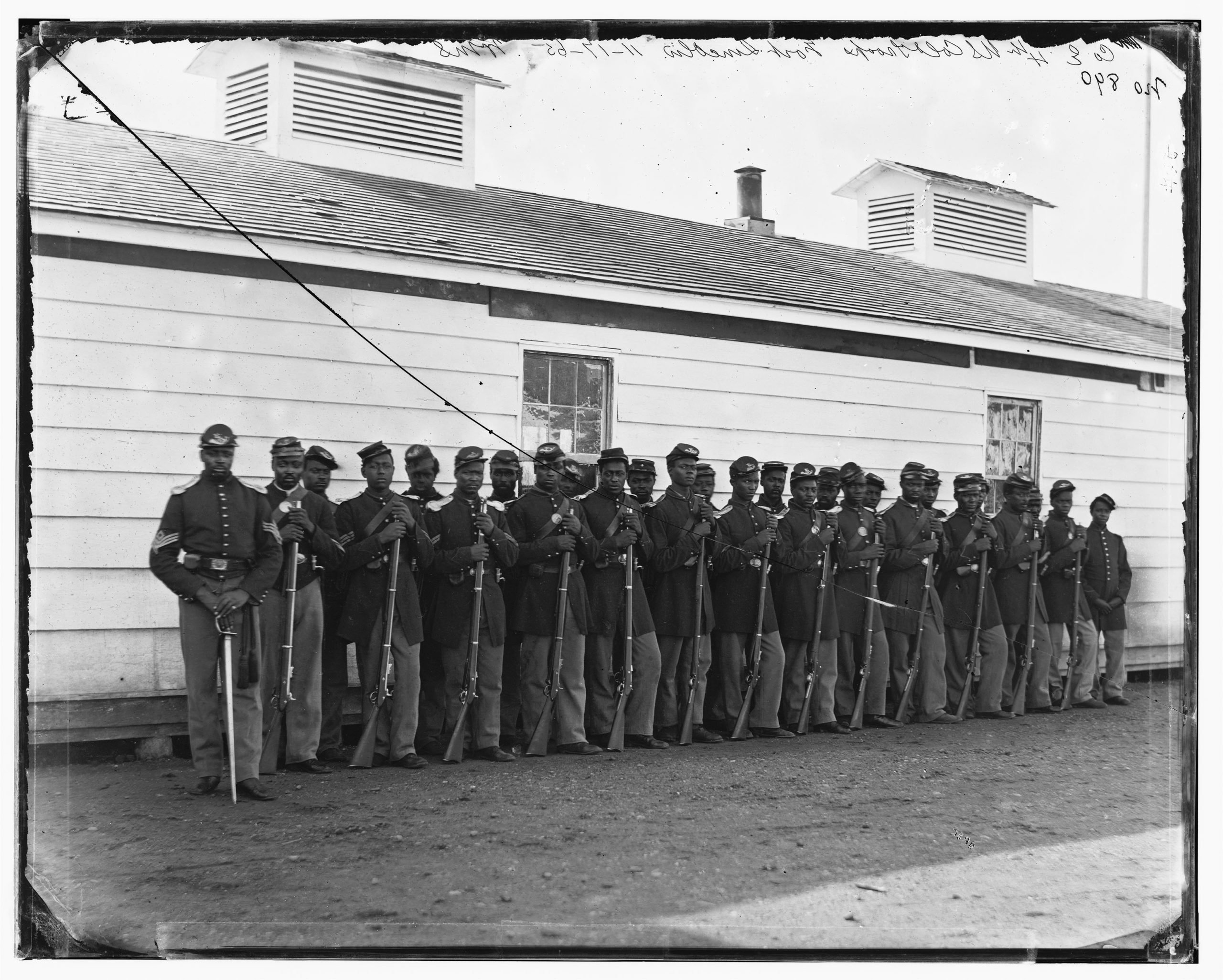

A scrimshaw is a carved piece of bone, teeth, or ivory, often made by whalers or sailors. This piece, made by an unknown artist near the North Carolina coast, dates to sometime after spring 1863, when the U.S. Army officially began to enlist Black soldiers. It depicts a Black soldier in uniform. Scrimshaw with portrait of Black soldier, c. 1863, inscription on whale-tooth, 5 x 2 1/2 inches (Chicago History Museum) Photographs of Black men in U.S. Army uniforms—which signaled their willingness to sacrifice their lives for the nation as well as their intent to submit to the rule of its government—created “the first possibility of imagined national black manhood,” in the words of scholar Maurice O. Wallace. Standing with their rifles upturned in two neat rows outside of a barracks, the men of Company E of the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry exemplify the discipline of citizen-soldiers in service to the government. William Morris Smith, Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln, District of Columbia, 1863–66, wet collodion glass negative (Library of Congress)

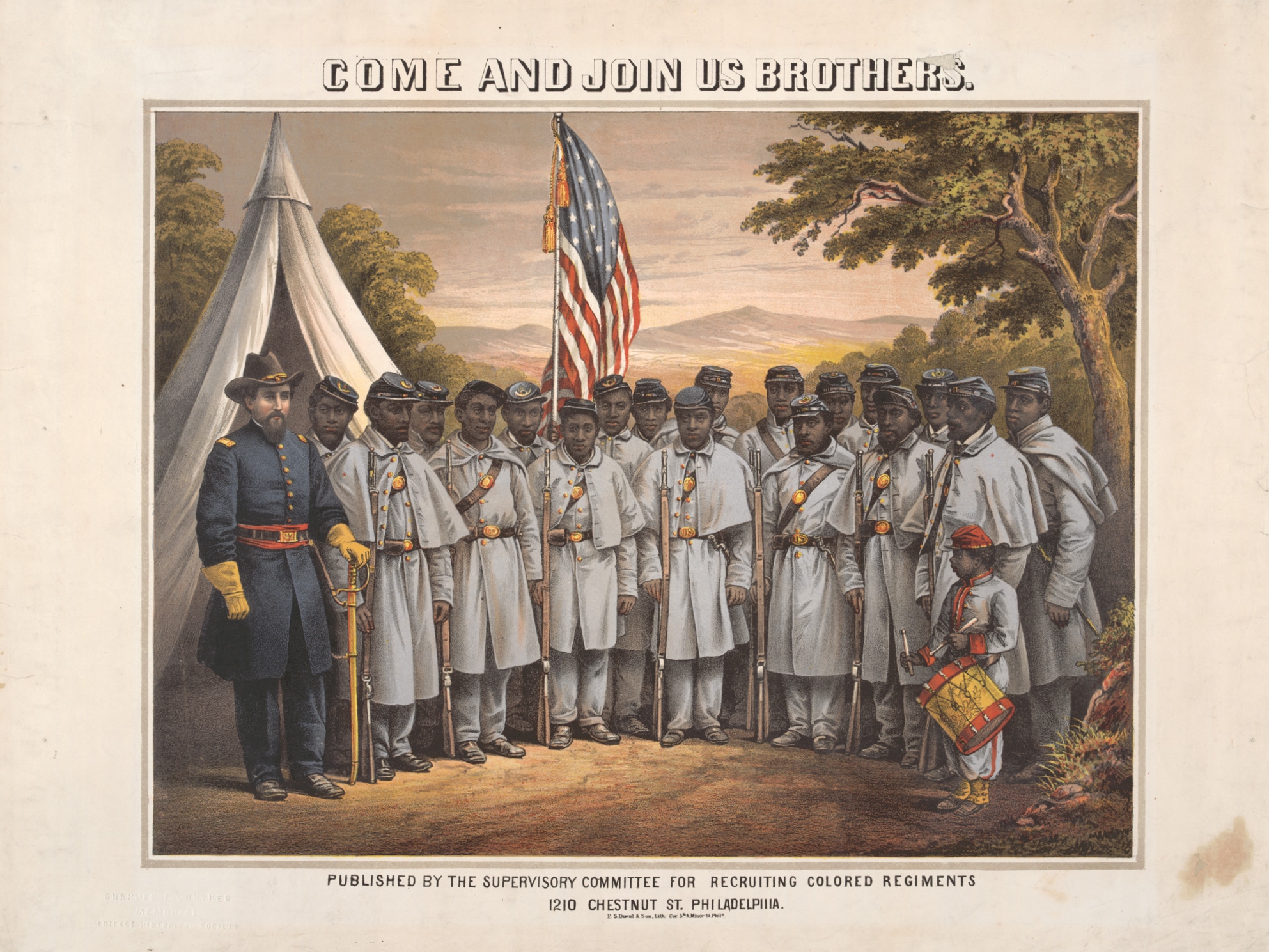

Photographs of Black men in U.S. Army uniforms—which signaled their willingness to sacrifice their lives for the nation as well as their intent to submit to the rule of its government—created “the first possibility of imagined national black manhood,” in the words of scholar Maurice O. Wallace. Standing with their rifles upturned in two neat rows outside of a barracks, the men of Company E of the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry exemplify the discipline of citizen-soldiers in service to the government. William Morris Smith, Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln, District of Columbia, 1863–66, wet collodion glass negative (Library of Congress) This poster is a recruitment broadside for Black men to join the U.S. Army. P. S. Duval and Son, Come and Join Us Brothers, 1864, lithograph, 14 x 18 inches (Chicago History Museum)

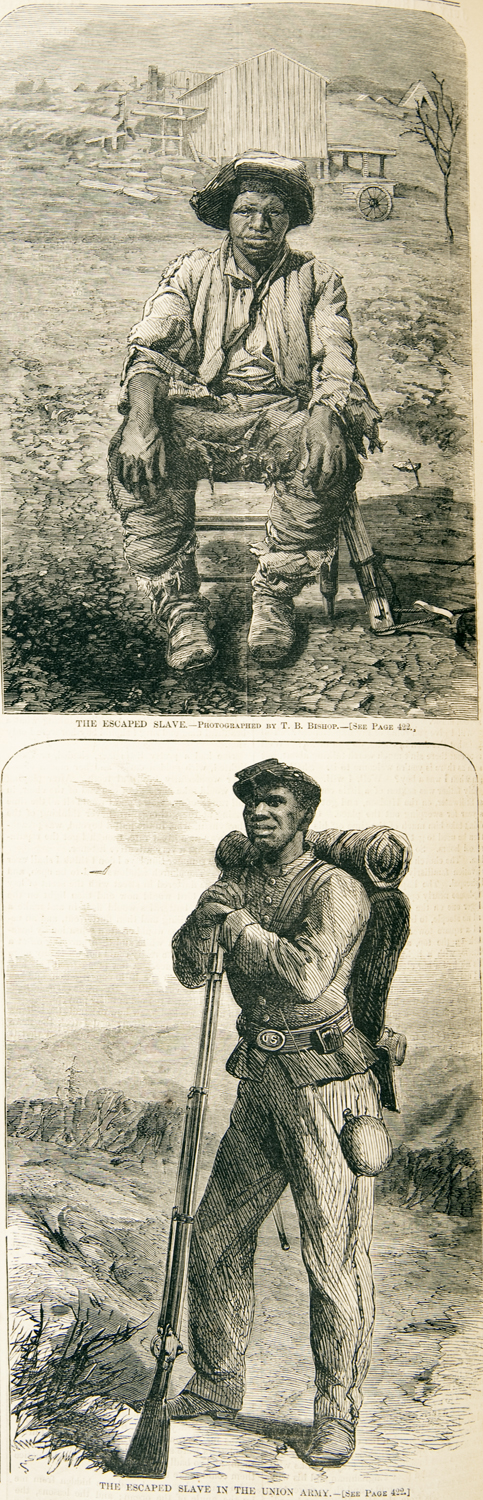

This poster is a recruitment broadside for Black men to join the U.S. Army. P. S. Duval and Son, Come and Join Us Brothers, 1864, lithograph, 14 x 18 inches (Chicago History Museum) These two engravings were created from photographs taken of the same man, after he had travelled hundreds of miles in a journey of self-emancipation and enlisted in the United States Colored Troops. T. B. Bishop (photographer), top: "The Escaped Slave," bottom: "The Escaped Slave in the Union Army," Harper's Weekly, July 2, 1864, p. 428, engraving (Newberry Library)

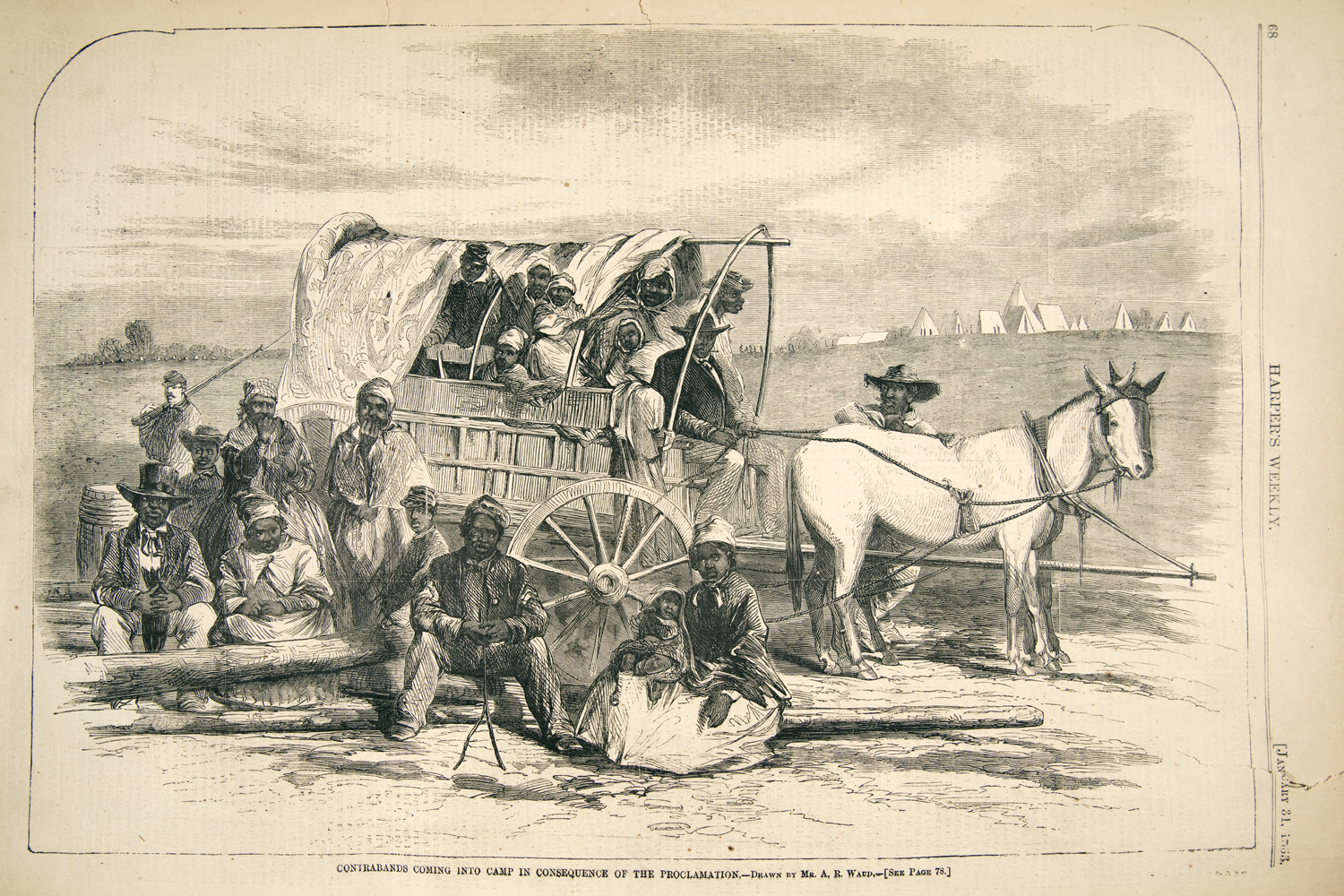

These two engravings were created from photographs taken of the same man, after he had travelled hundreds of miles in a journey of self-emancipation and enlisted in the United States Colored Troops. T. B. Bishop (photographer), top: "The Escaped Slave," bottom: "The Escaped Slave in the Union Army," Harper's Weekly, July 2, 1864, p. 428, engraving (Newberry Library) Alfred Waud's image shows a group of emancipated men, women, and children gathered around their horse and covered wagon after reaching the U.S. Army. The tents in the distance could be either a U.S. Army camp or a refugee camp, which were set up to help clothe and feed self-emancipated men and women who had come into U.S. Army lines seeking freedom. This image was made only one month after the Emancipation Proclamation became official. Alfred R. Waud, Contrabands Coming into Camp in Consequence of the Proclamation January 31, 1863, engraving from Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, vol. 9, no. 318, p. 68 (Newberry Library)

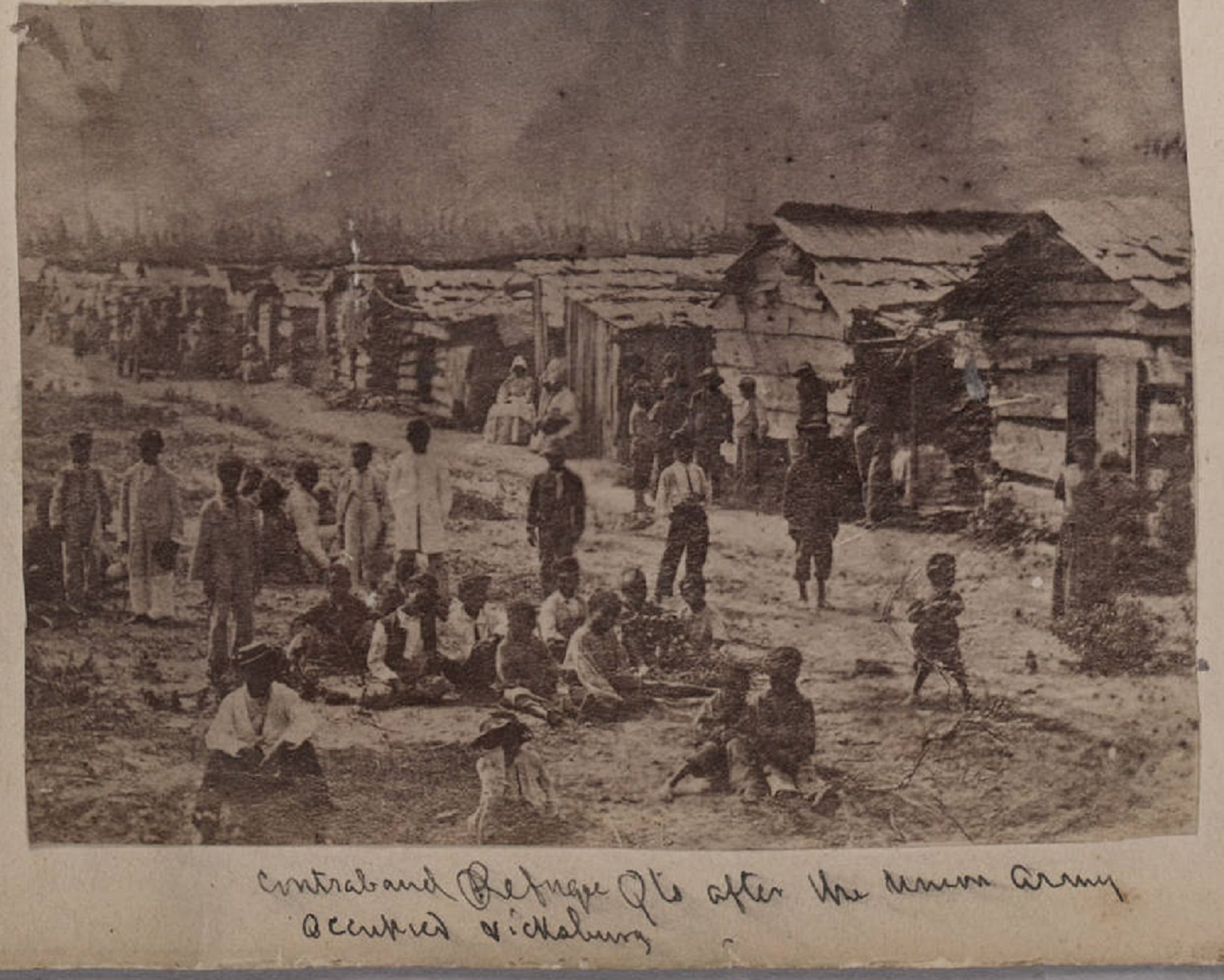

Alfred Waud's image shows a group of emancipated men, women, and children gathered around their horse and covered wagon after reaching the U.S. Army. The tents in the distance could be either a U.S. Army camp or a refugee camp, which were set up to help clothe and feed self-emancipated men and women who had come into U.S. Army lines seeking freedom. This image was made only one month after the Emancipation Proclamation became official. Alfred R. Waud, Contrabands Coming into Camp in Consequence of the Proclamation January 31, 1863, engraving from Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, vol. 9, no. 318, p. 68 (Newberry Library) Historians estimate that one million enslaved people freed themselves between 1861 and 1865, and approximately 500,000 lived in refugee camps constructed by the U.S. Army or by refugees themselves. This photograph, likely cut from a carte-de-visite, shows refugees in a settlement at Helena, Arkansas, one of the nearly 300 camps managed by the U.S. War Department. Contraband Refugee Quarters after the Union Army occupied Vicksburg, 1863–65 (Huntington Library)

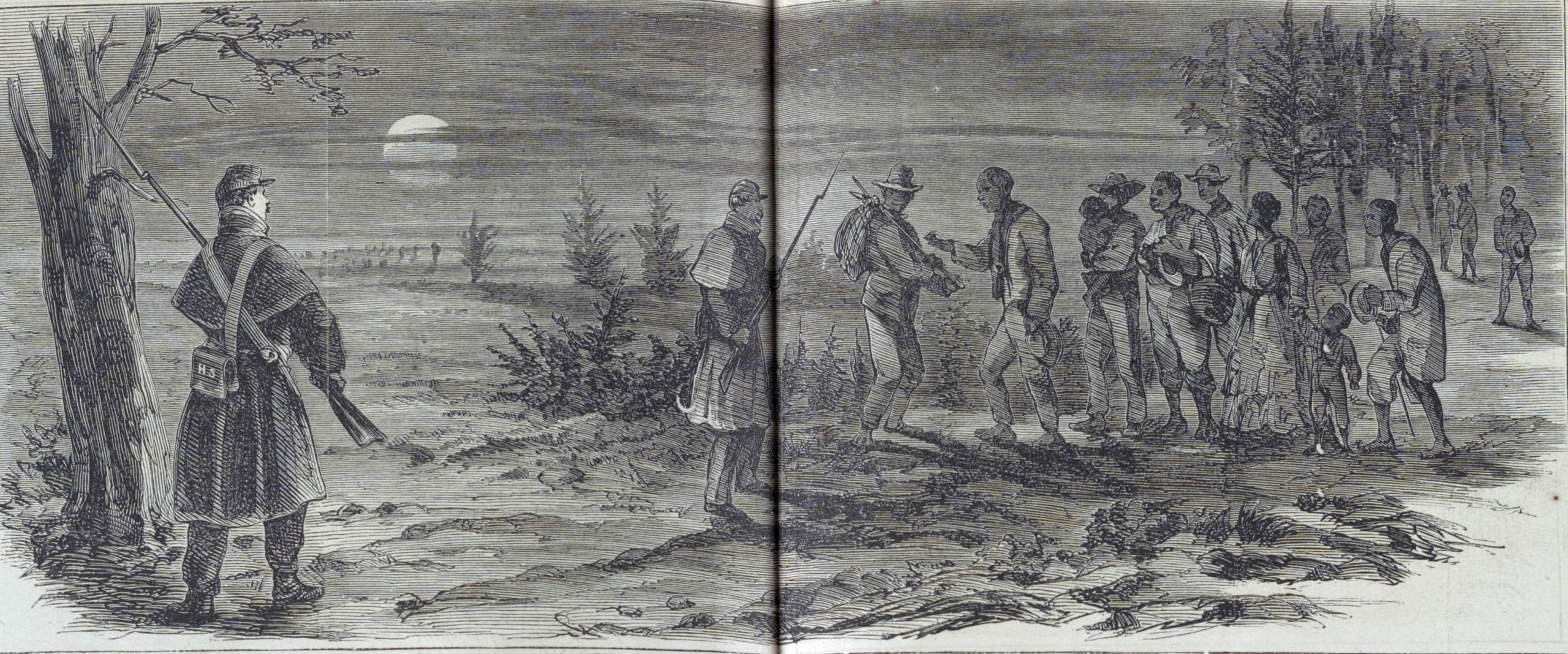

Historians estimate that one million enslaved people freed themselves between 1861 and 1865, and approximately 500,000 lived in refugee camps constructed by the U.S. Army or by refugees themselves. This photograph, likely cut from a carte-de-visite, shows refugees in a settlement at Helena, Arkansas, one of the nearly 300 camps managed by the U.S. War Department. Contraband Refugee Quarters after the Union Army occupied Vicksburg, 1863–65 (Huntington Library) Self-emancipation for Black men and women increased significantly during the war as U.S. Army camps became more accessible sites to which enslaved people could escape and request asylum. At first, U.S. government policy required the return of escapees to their enslavers, but as U.S. generals resisted this policy, self-emancipated men and women became recognized as "contraband" (or refugees) by the U.S. Army and were allowed to stay and work at the army camps. "Refugees meeting U.S. Army officers at night and requesting asylum" detail from "Stampede among the Negroes in Virginia—their arrival at Fortress Monroe / from sketches by our Special Artist in Fortress Monroe," Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 8, 1861, wood engraving ; 40.4 x 54.3 cm (Library of Congress)

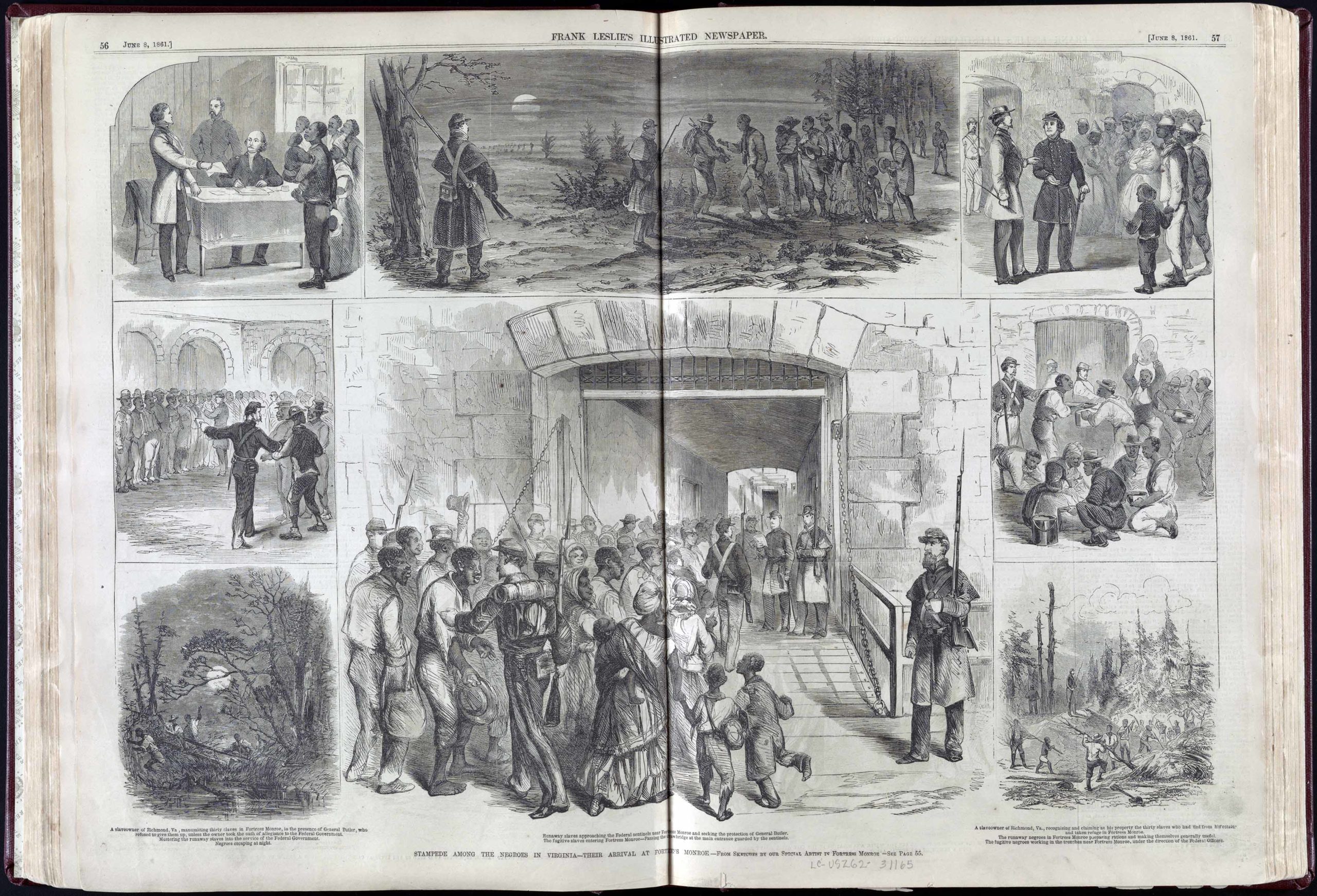

Self-emancipation for Black men and women increased significantly during the war as U.S. Army camps became more accessible sites to which enslaved people could escape and request asylum. At first, U.S. government policy required the return of escapees to their enslavers, but as U.S. generals resisted this policy, self-emancipated men and women became recognized as "contraband" (or refugees) by the U.S. Army and were allowed to stay and work at the army camps. "Refugees meeting U.S. Army officers at night and requesting asylum" detail from "Stampede among the Negroes in Virginia—their arrival at Fortress Monroe / from sketches by our Special Artist in Fortress Monroe," Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 8, 1861, wood engraving ; 40.4 x 54.3 cm (Library of Congress) This two-page spread printed in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper reflects northern ambiguity toward the subject of emancipation in the first months of the war. In a series of vignettes that depict the increasing numbers of enslaved men and women who sought freedom by escaping to U.S. Army camps, the spread offers both praise for the the U.S. Army for taking in the refugees as well as as instances of caricature and dehumanizing language to describe the escapees. "Stampede among the Negroes in Virginia—their arrival at Fortress Monroe / from sketches by our Special Artist in Fortress Monroe," Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 8, 1861, pp. 56–57, wood engraving, 40.4 x 54.3 cm (Library of Congress)

This two-page spread printed in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper reflects northern ambiguity toward the subject of emancipation in the first months of the war. In a series of vignettes that depict the increasing numbers of enslaved men and women who sought freedom by escaping to U.S. Army camps, the spread offers both praise for the the U.S. Army for taking in the refugees as well as as instances of caricature and dehumanizing language to describe the escapees. "Stampede among the Negroes in Virginia—their arrival at Fortress Monroe / from sketches by our Special Artist in Fortress Monroe," Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 8, 1861, pp. 56–57, wood engraving, 40.4 x 54.3 cm (Library of Congress) Johnson depicts an enslaved family crossing a Civil War battlefield on horseback to reach safety and freedom with the U.S. Army. The artist claims to have witnessed this dangerous, early morning act of self-emancipation and made a few different versions of this painting. Eastman Johnson, A Ride for Liberty — The Fugitive Slaves, c. 1862, oil on paper board, 55.8 x 66.4 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

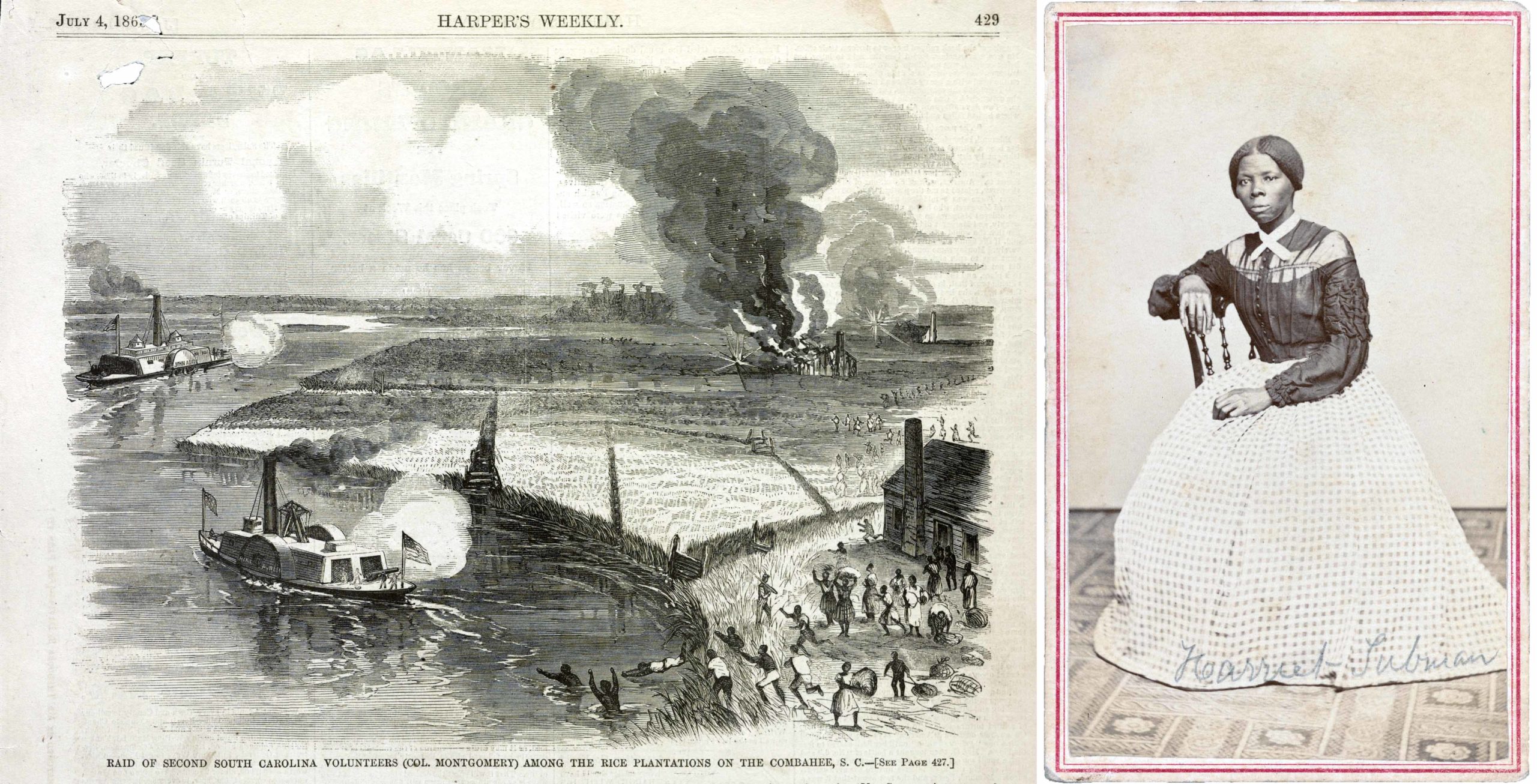

Johnson depicts an enslaved family crossing a Civil War battlefield on horseback to reach safety and freedom with the U.S. Army. The artist claims to have witnessed this dangerous, early morning act of self-emancipation and made a few different versions of this painting. Eastman Johnson, A Ride for Liberty — The Fugitive Slaves, c. 1862, oil on paper board, 55.8 x 66.4 cm (Brooklyn Museum) Harriet Tubman, who had emancipated herself in 1849, became the first woman to lead a major military operation in the United States when she led 150 members of the U.S. 2nd South Carolina Volunteers—a Black regiment—in a raid on Combahee Ferry in South Carolina. Tubman and the soldiers rescued at least 700 enslaved Black people on the night of June 1, 1863. Left: “Raid Of Second South Carolina Volunteers (Col. Montgomery) Among The Rice Plantations On The Combahee, S.C.,” Harper’s Weekly, July 4, 1863, p. 429, wood engraving, 27.6 x 39.5 cm (Library of Congress); right: Benjamin F. Powelson, Portrait of Harriet Tubman, c. 1868–69, albumen carte-de-visite, 10 x 6 cm (Library of Congress)

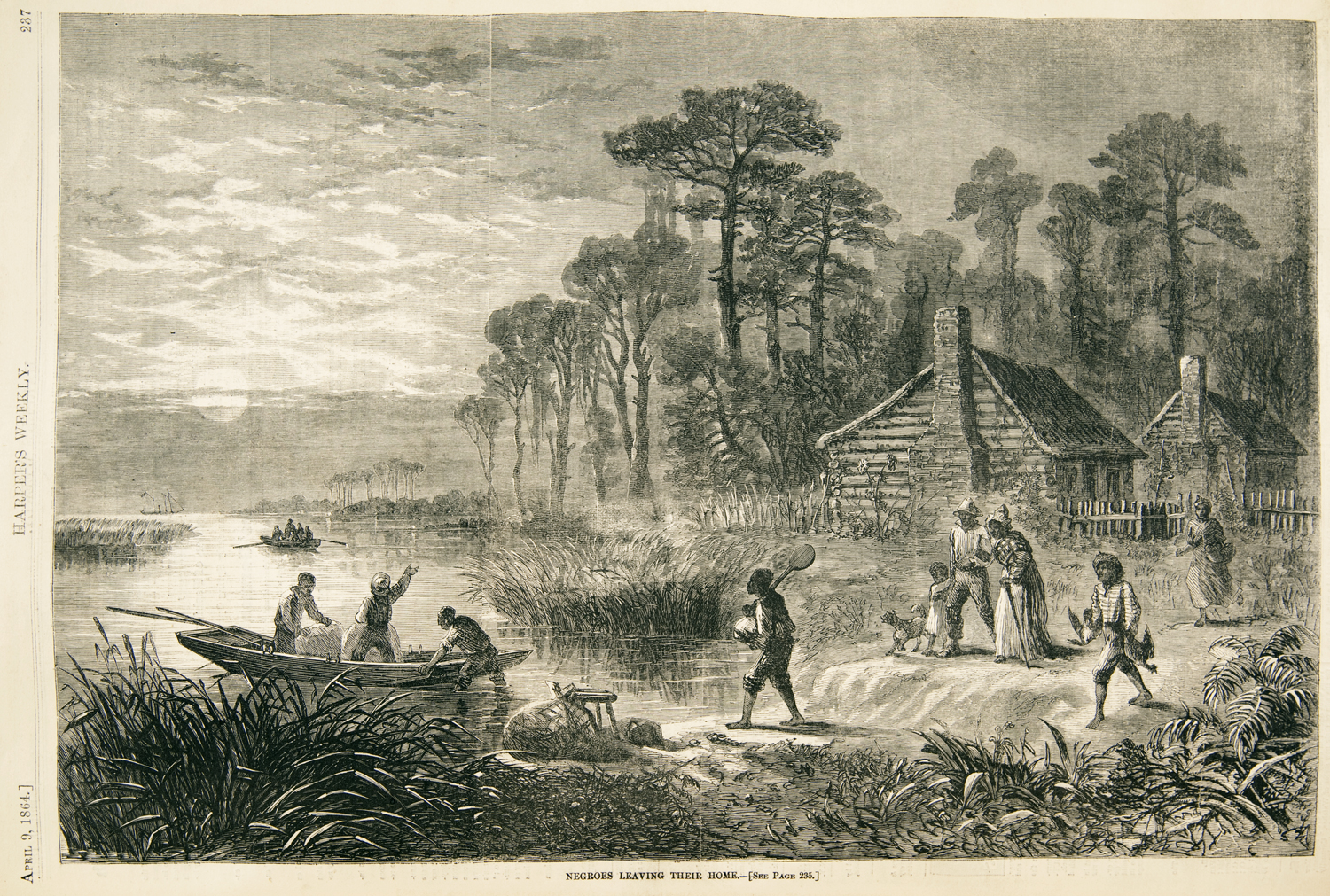

Harriet Tubman, who had emancipated herself in 1849, became the first woman to lead a major military operation in the United States when she led 150 members of the U.S. 2nd South Carolina Volunteers—a Black regiment—in a raid on Combahee Ferry in South Carolina. Tubman and the soldiers rescued at least 700 enslaved Black people on the night of June 1, 1863. Left: “Raid Of Second South Carolina Volunteers (Col. Montgomery) Among The Rice Plantations On The Combahee, S.C.,” Harper’s Weekly, July 4, 1863, p. 429, wood engraving, 27.6 x 39.5 cm (Library of Congress); right: Benjamin F. Powelson, Portrait of Harriet Tubman, c. 1868–69, albumen carte-de-visite, 10 x 6 cm (Library of Congress) In this illustration, an unknown artist has drawn enslaved men, women, and children as they flee their homes by boat under the light of a full moon. "Negroes Leaving Their Home," Harper's Weekly, April 9, 1864, engraving (Newberry Library)

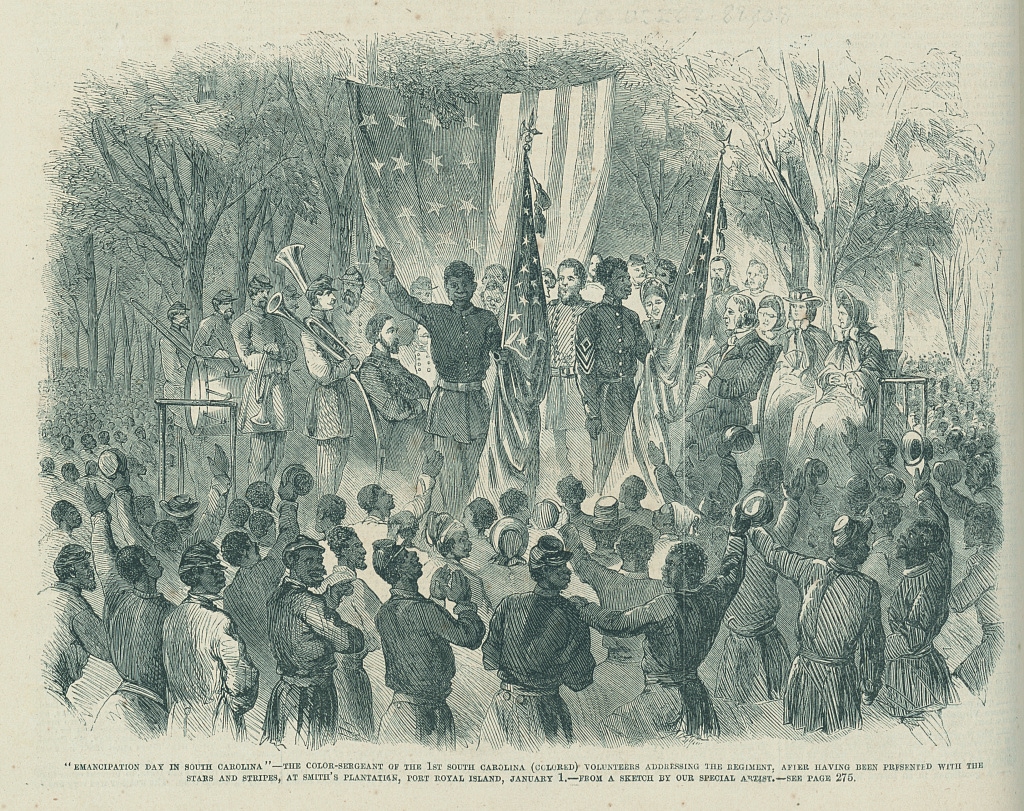

In this illustration, an unknown artist has drawn enslaved men, women, and children as they flee their homes by boat under the light of a full moon. "Negroes Leaving Their Home," Harper's Weekly, April 9, 1864, engraving (Newberry Library) The Lost Cause (a mythology that rewrote the causes of the Civil War to erase the role of slavery) was more than wistful nostalgia. With it came efforts to quash southern Black celebrations of Confederate defeat and the end of slavery, like parades and dances held on the Fourth of July and on Emancipation Day. In this image, the First South Carolina Volunteers’ color guard addresses a joyful crowd of African Americans after the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. “‘Emancipation Day in South Carolina’—the Color-Sergeant of the 1st South Carolina (Colored) Volunteers addressing the regiment, after having been presented with the Stars and Stripes, at Smith’s plantation, Port Royal Island, January 1 / From a sketch by our special artist.,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 24, 1863, wood engraving, 40 x 27 cm (Library of Congress)

The Lost Cause (a mythology that rewrote the causes of the Civil War to erase the role of slavery) was more than wistful nostalgia. With it came efforts to quash southern Black celebrations of Confederate defeat and the end of slavery, like parades and dances held on the Fourth of July and on Emancipation Day. In this image, the First South Carolina Volunteers’ color guard addresses a joyful crowd of African Americans after the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. “‘Emancipation Day in South Carolina’—the Color-Sergeant of the 1st South Carolina (Colored) Volunteers addressing the regiment, after having been presented with the Stars and Stripes, at Smith’s plantation, Port Royal Island, January 1 / From a sketch by our special artist.,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 24, 1863, wood engraving, 40 x 27 cm (Library of Congress)![The Effects of the Proclamation [Freed Negroes Coming into our Lines at Newbern, North Carolina], engraving from Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, vol 9, no.321, February 21, 1863, p. 116 (Newberry Library) The Effects of the Proclamation [Freed Negroes Coming into our Lines at Newbern, North Carolina], engraving from Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, vol 9, no.321, February 21, 1863, p. 116 (Newberry Library)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-Effects-of-the-Proclamation_Emancipation.jpeg) This image shows a large group of recently emancipated men, women, and children marching next to the U.S. Army. The artist, an unnamed solider in the regiment, explained in an accompanying letter that the group "said that it was known far and wide that the President has declared the slaves free,” a reference to the Emancipation Proclamation. "The Effects of the Proclamation—Freed Negroes Coming into our Lines at Newbern, North Carolina," Harper's Weekly, February 21, 1863, p. 116, engraving (Newberry Library)

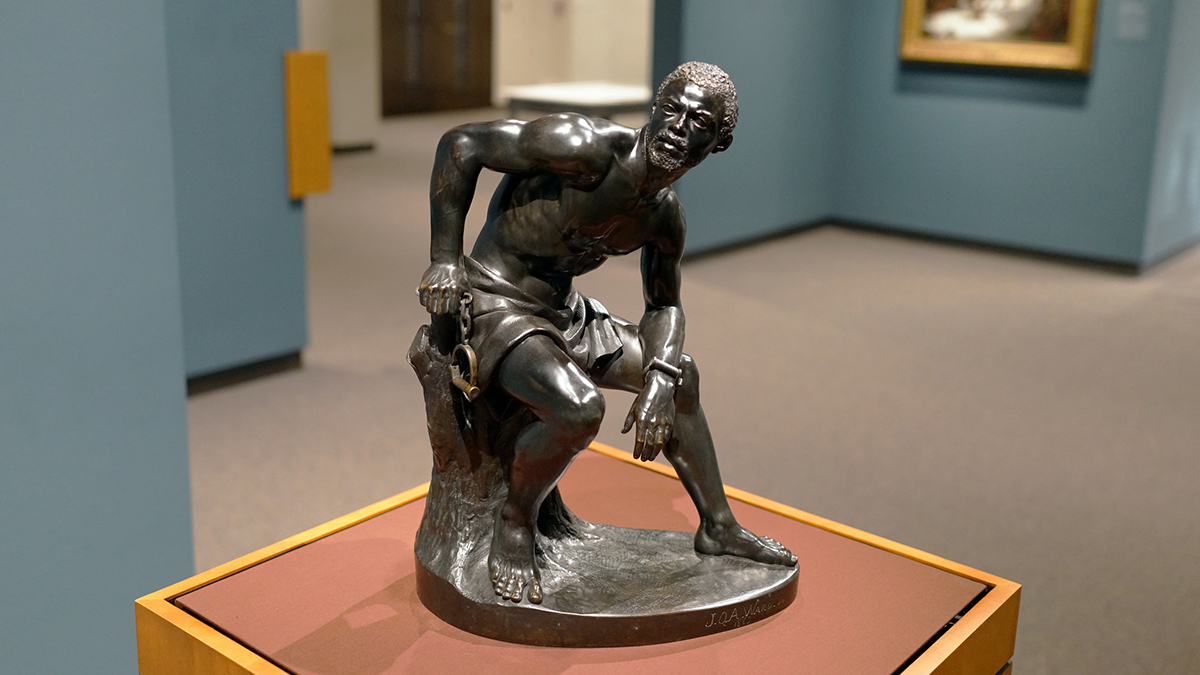

This image shows a large group of recently emancipated men, women, and children marching next to the U.S. Army. The artist, an unnamed solider in the regiment, explained in an accompanying letter that the group "said that it was known far and wide that the President has declared the slaves free,” a reference to the Emancipation Proclamation. "The Effects of the Proclamation—Freed Negroes Coming into our Lines at Newbern, North Carolina," Harper's Weekly, February 21, 1863, p. 116, engraving (Newberry Library) John Quincy Adams Ward's sculpture directly responds to the Emancipation Proclamation. An emancipated Black man is depicted as being in charge of his own freedom; no white man is included as the agent of his liberation. John Quincy Adams Ward, The Freedman, 1863, bronze (Amon Carter Museum of American Art)

John Quincy Adams Ward's sculpture directly responds to the Emancipation Proclamation. An emancipated Black man is depicted as being in charge of his own freedom; no white man is included as the agent of his liberation. John Quincy Adams Ward, The Freedman, 1863, bronze (Amon Carter Museum of American Art) David Gilmour Blythe's painting depicts an emancipated man who flees from a ruined Virginia plantation with bits of chains still dangling from his ankle. In this way, the image signifies the end of slavery’s hold. Blythe does not, however, depict the freed Black man with dignity. His portrayal draws on racist stereotypes, and he appears beaten down, close to giving up. At the time, many northerners, like Blythe, believed that emancipated Black people faced an unknown future as they began their lives of freedom. David Gilmour Blythe, Old Virginia Home, 1864, oil on canvas, 20 3/4 x 28 3/4 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

David Gilmour Blythe's painting depicts an emancipated man who flees from a ruined Virginia plantation with bits of chains still dangling from his ankle. In this way, the image signifies the end of slavery’s hold. Blythe does not, however, depict the freed Black man with dignity. His portrayal draws on racist stereotypes, and he appears beaten down, close to giving up. At the time, many northerners, like Blythe, believed that emancipated Black people faced an unknown future as they began their lives of freedom. David Gilmour Blythe, Old Virginia Home, 1864, oil on canvas, 20 3/4 x 28 3/4 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) In the 1860s, newspapers could not yet reproduce photographs, so “special artists” were sent to travel with armies to sketch the action. These artists mailed their drawings to newspaper offices so engravers could interpret them for mass distribution. Winslow Homer’s sketch of a scene of officers and enlisted men discussing strategy outside a farmhouse near Yorktown was later printed as part of a larger page of scenes illustrating the war. Winslow Homer, Reconnaissance in force by General Gorman before Yorktown, 1862, graphite with brush and gray wash on cream wove paper, 21 x 33.7 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

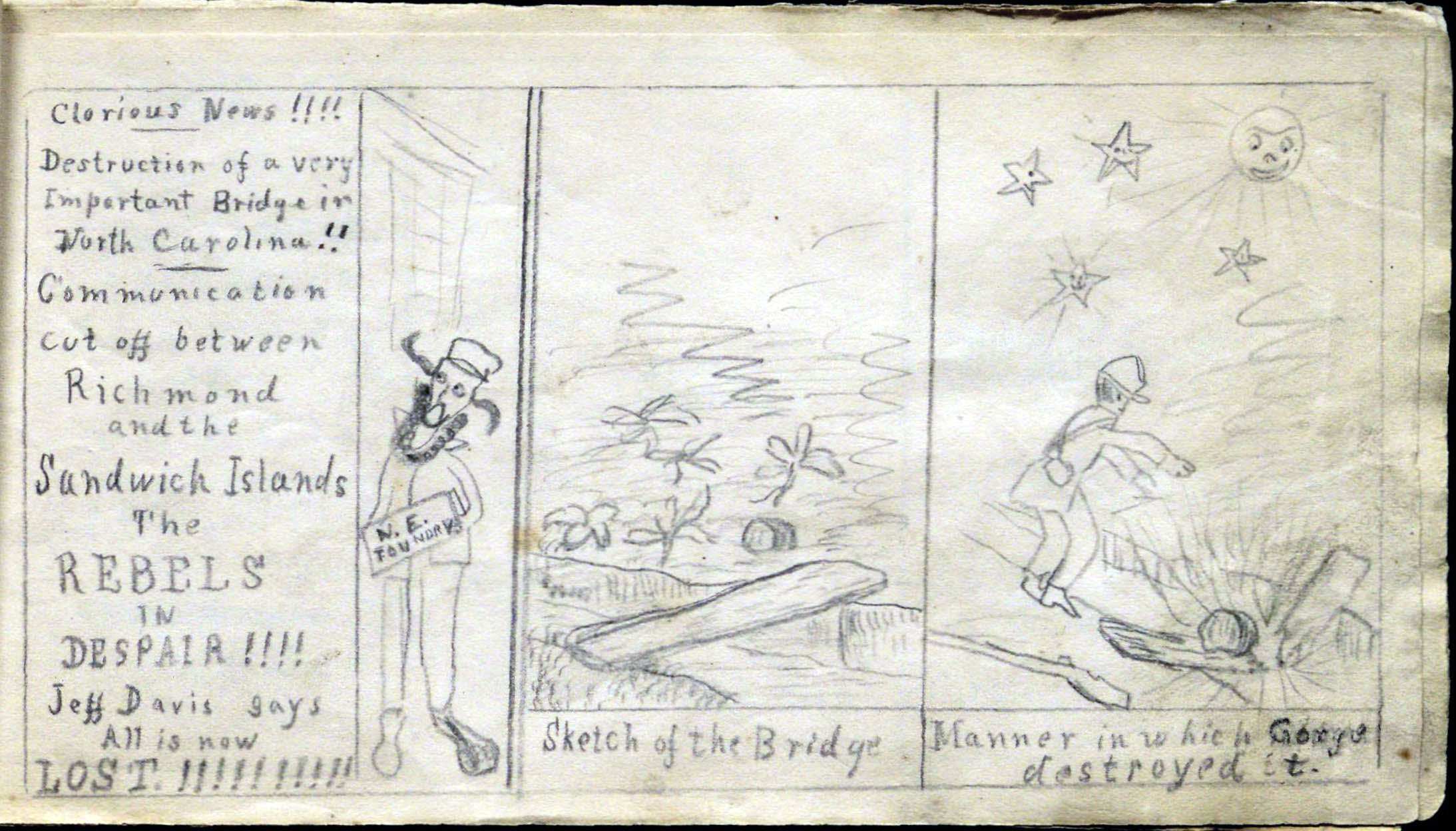

In the 1860s, newspapers could not yet reproduce photographs, so “special artists” were sent to travel with armies to sketch the action. These artists mailed their drawings to newspaper offices so engravers could interpret them for mass distribution. Winslow Homer’s sketch of a scene of officers and enlisted men discussing strategy outside a farmhouse near Yorktown was later printed as part of a larger page of scenes illustrating the war. Winslow Homer, Reconnaissance in force by General Gorman before Yorktown, 1862, graphite with brush and gray wash on cream wove paper, 21 x 33.7 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) Some soldier-artists captured their war experiences in drawings, completed while in camp or years afterward when recalling the scenes of battle. One unknown artist, a soldier in the 44th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry stationed in New Bern, North Carolina, drew a series of cartoons in his diary contrasting the northern press’s breathless coverage of the war with the far less romantic reality. “Glorious News!!!!” in “A Few Scenes in the Life of A ‘SOJER’ in the Mass 44th,” 1863, graphite on paper (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

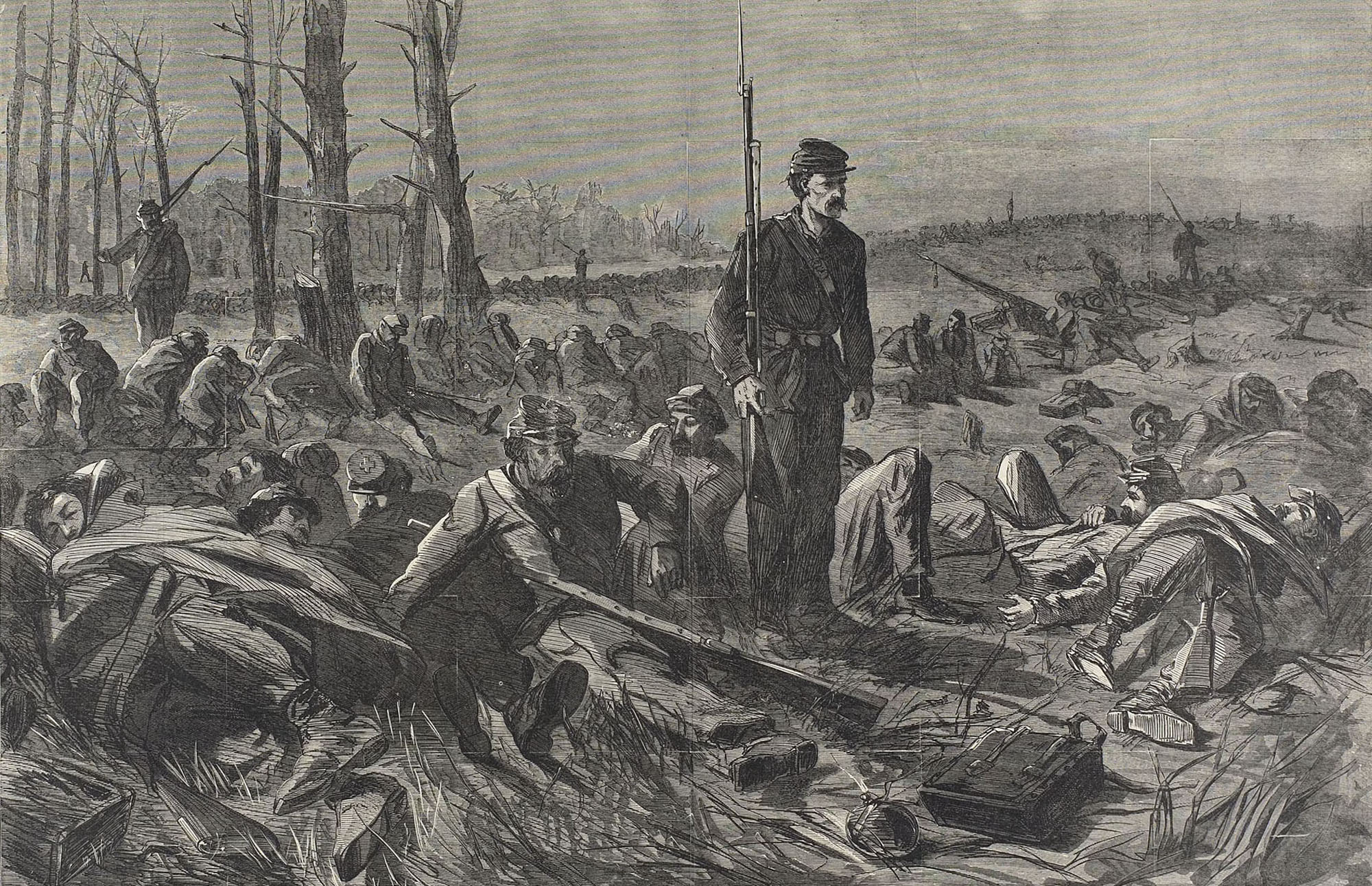

Some soldier-artists captured their war experiences in drawings, completed while in camp or years afterward when recalling the scenes of battle. One unknown artist, a soldier in the 44th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry stationed in New Bern, North Carolina, drew a series of cartoons in his diary contrasting the northern press’s breathless coverage of the war with the far less romantic reality. “Glorious News!!!!” in “A Few Scenes in the Life of A ‘SOJER’ in the Mass 44th,” 1863, graphite on paper (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History) The phrase "sleeping on their arms" refers to the way that men on the march were allowed to sleep briefly but not to set up camp. To be ready to move again shortly, or to defend against sudden attack, they lie down with their arms, or weapons, nearby. Artist Winslow Homer has taken care to show the way the men slept—with coats thrown over their faces as blankets, heads propped on knapsacks or canteens, rifles at hand. He also suggests how dangerous it was to sleep in the open, by showing soldiers assigned as sentries and for picket duty standing guard. Winslow Homer, Army of the Potomac—Sleeping on Their Arms, 1864, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly, May 21, 1864, 13 5/8 x 20 3/4 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

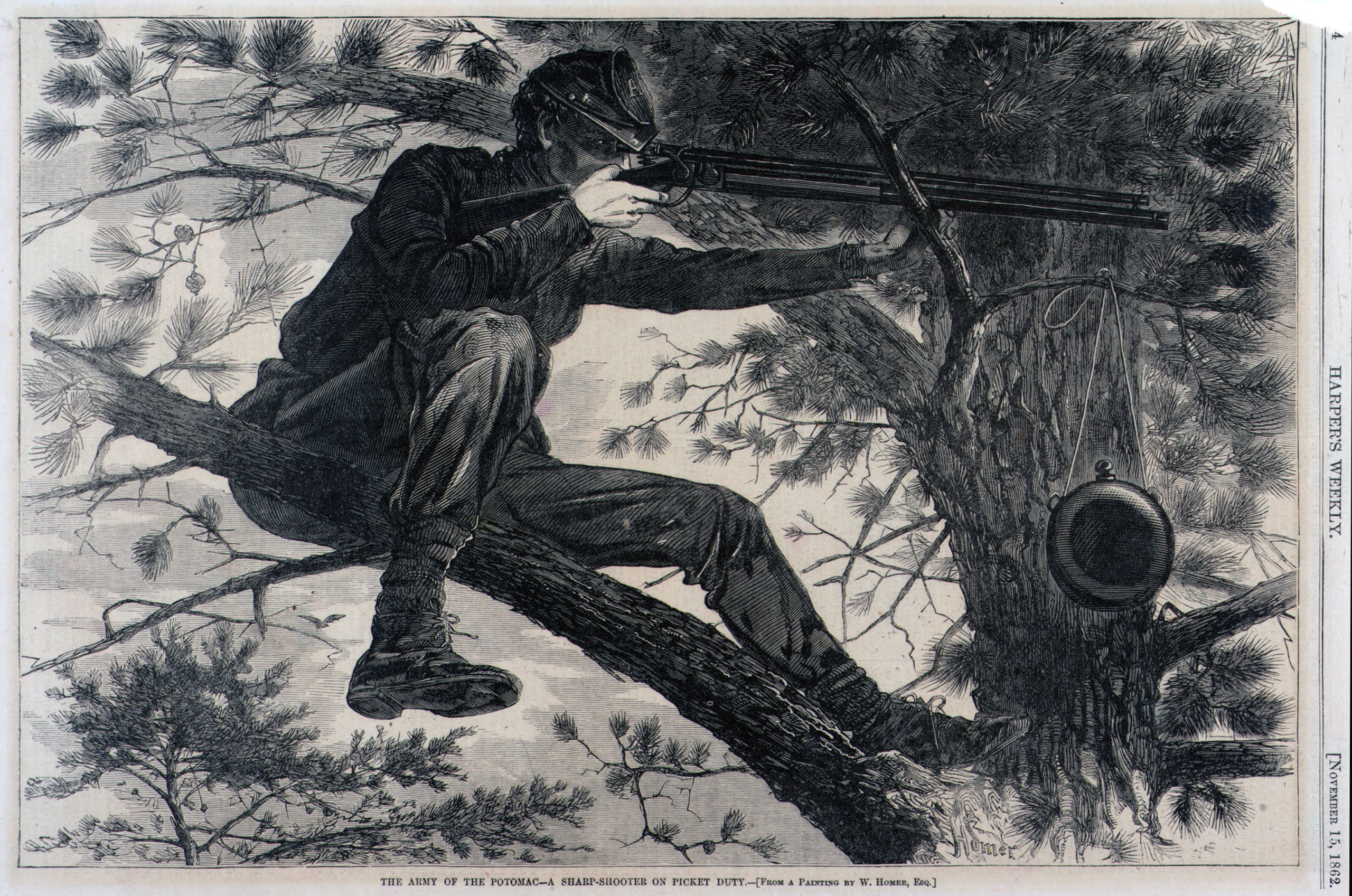

The phrase "sleeping on their arms" refers to the way that men on the march were allowed to sleep briefly but not to set up camp. To be ready to move again shortly, or to defend against sudden attack, they lie down with their arms, or weapons, nearby. Artist Winslow Homer has taken care to show the way the men slept—with coats thrown over their faces as blankets, heads propped on knapsacks or canteens, rifles at hand. He also suggests how dangerous it was to sleep in the open, by showing soldiers assigned as sentries and for picket duty standing guard. Winslow Homer, Army of the Potomac—Sleeping on Their Arms, 1864, wood engraving published by Harper's Weekly, May 21, 1864, 13 5/8 x 20 3/4 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) Winslow Homer was one of a number of artist reporters who worked for Harper’s Weekly Illustrated Magazine during the U.S. Civil War. He sent sketches from the field back to New York to be transferred into engravings included in news of the ongoing conflict. Sharpshooters were a new, elite rank of soldier during the Civil War, both feared and admired for their exceptional skill and unique role in battle. Winslow Homer, "The Army of the Potomac—A Sharpshooter on Picket Duty," Harper’s Weekly, November 15, 1862, wood engraving (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

Winslow Homer was one of a number of artist reporters who worked for Harper’s Weekly Illustrated Magazine during the U.S. Civil War. He sent sketches from the field back to New York to be transferred into engravings included in news of the ongoing conflict. Sharpshooters were a new, elite rank of soldier during the Civil War, both feared and admired for their exceptional skill and unique role in battle. Winslow Homer, "The Army of the Potomac—A Sharpshooter on Picket Duty," Harper’s Weekly, November 15, 1862, wood engraving (Smithsonian American Art Museum) It was difficult, if not impossible, to photograph scenes of battle during the U.S. Civil War. Not only was it dangerous, but the bulky cameras, long exposures, and collodion-on-glass, or wet-plate, technology that photographers were using made the process very challenging. As evidence of this reality, the caption for this photograph states that “This picture was made as the guns were engaging the enemy, the gunners…calling to the photographer to hurry his wagon out of the way, unless he was anxious to figure in the list of casualties.” Timothy O'Sullivan, Incidents of the War: Battery D, 5th U.S. Artillery in Action, 1863, albumen print from collodion wet plate negative, 6 15/16 x 9 1/16 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

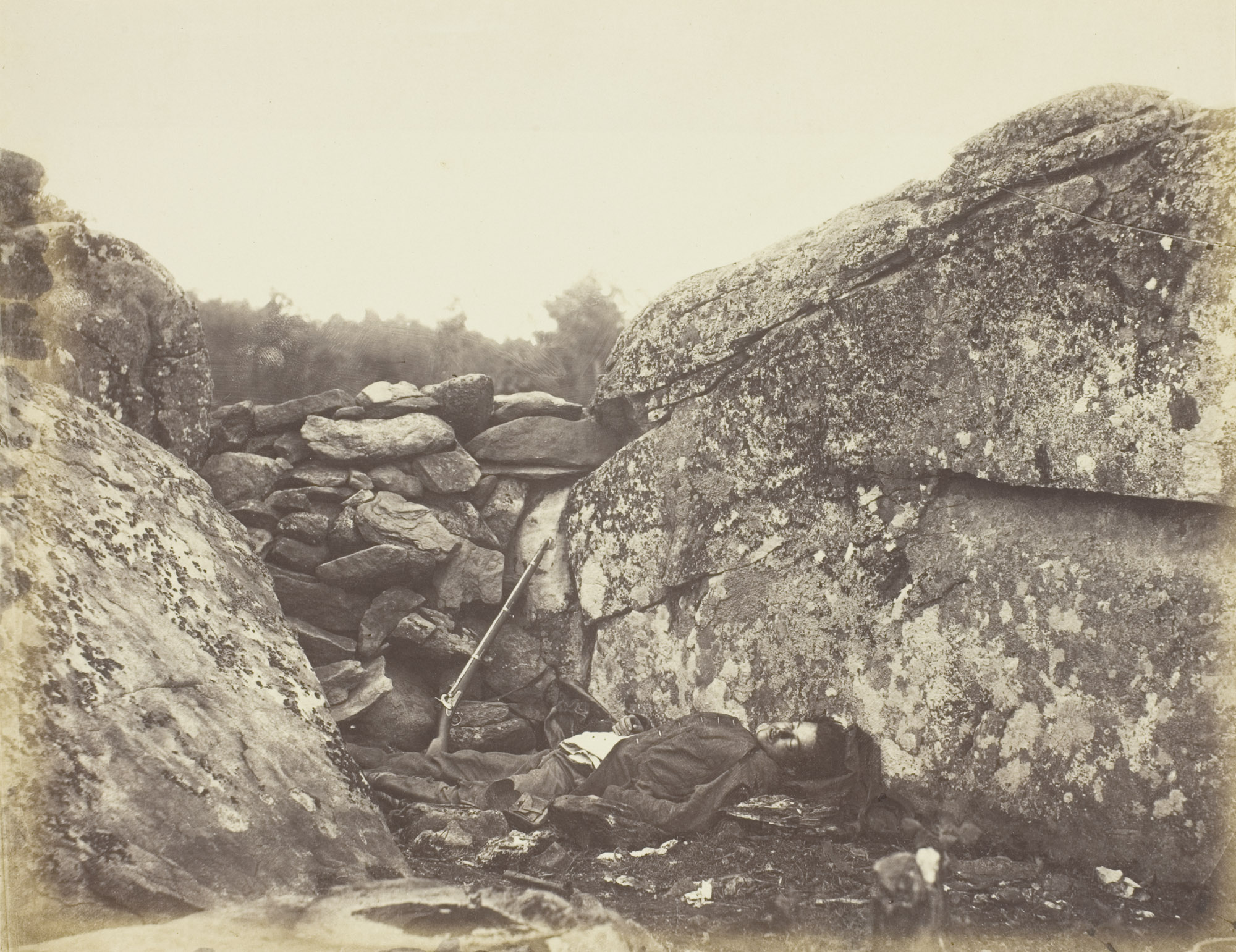

It was difficult, if not impossible, to photograph scenes of battle during the U.S. Civil War. Not only was it dangerous, but the bulky cameras, long exposures, and collodion-on-glass, or wet-plate, technology that photographers were using made the process very challenging. As evidence of this reality, the caption for this photograph states that “This picture was made as the guns were engaging the enemy, the gunners…calling to the photographer to hurry his wagon out of the way, unless he was anxious to figure in the list of casualties.” Timothy O'Sullivan, Incidents of the War: Battery D, 5th U.S. Artillery in Action, 1863, albumen print from collodion wet plate negative, 6 15/16 x 9 1/16 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) While walking the bloody fields of Gettysburg, Alexander Gardner found and photographed this fallen Confederate sharpshooter. Gardner said he took this photograph three days after the battle, noting, “The fields were thickly strewn with Confederate dead and wounded, dismounted guns, wrecked caissons, and the debris of a broken army.” Alexander Gardner, Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, 1863, albumen print from collodion wet plate negative, 6 15/16 x 9 1/16 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago)

While walking the bloody fields of Gettysburg, Alexander Gardner found and photographed this fallen Confederate sharpshooter. Gardner said he took this photograph three days after the battle, noting, “The fields were thickly strewn with Confederate dead and wounded, dismounted guns, wrecked caissons, and the debris of a broken army.” Alexander Gardner, Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, 1863, albumen print from collodion wet plate negative, 6 15/16 x 9 1/16 inches (The Art Institute of Chicago) This scene depicts an important victory for General Grant and the U.S. Army in the early years of the war. After the war, Paul D. Philippoteaux, a French artist, made this painting along with a number of panoramic images of major battles. Here he captures the wintry and desolate surroundings of Fort Donelson and includes such details as wounded men lying near the fire in the foreground and two Black men carrying an injured soldier in the lower right hand corner. Paul D. Philippoteaux, General Grant at Fort Donelson, c. 1870–75, Oil on canvas 18 x 25 inches (Chicago History Museum)

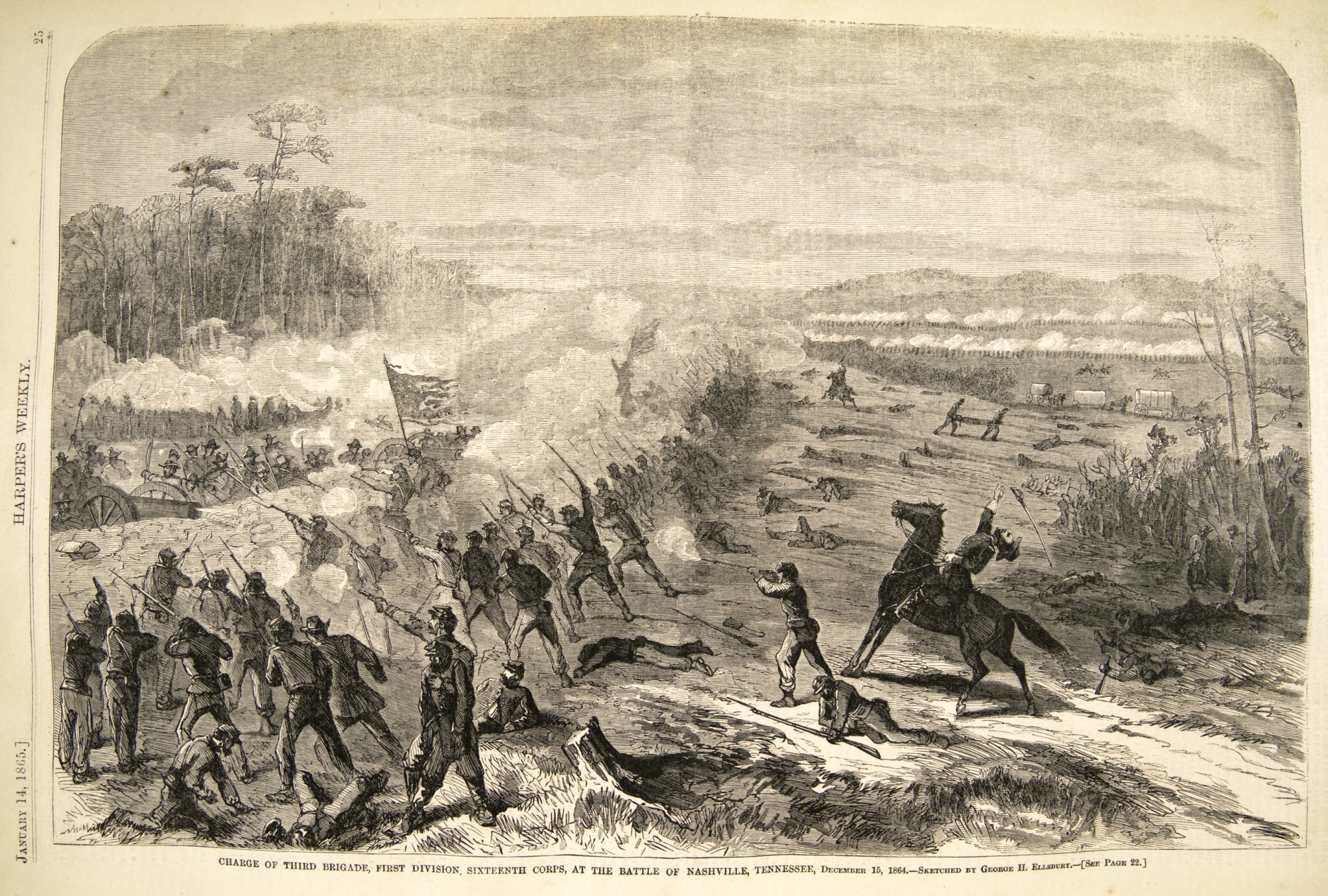

This scene depicts an important victory for General Grant and the U.S. Army in the early years of the war. After the war, Paul D. Philippoteaux, a French artist, made this painting along with a number of panoramic images of major battles. Here he captures the wintry and desolate surroundings of Fort Donelson and includes such details as wounded men lying near the fire in the foreground and two Black men carrying an injured soldier in the lower right hand corner. Paul D. Philippoteaux, General Grant at Fort Donelson, c. 1870–75, Oil on canvas 18 x 25 inches (Chicago History Museum) The Battle of Nashville was fought outside the city on December 15 and 16, 1863, resulting in a massive and decisive U.S. Army victory. Notably, the initial U.S. Army attack (not shown here) was led by two brigades of the 13th U.S. Colored Troops Infantry. The battle effectively destroyed the Confederate Army of Tennessee, its second largest force, and left the South weakened and vulnerable. George H. Ellsbury, Charge of the Third Brigade, First Division, Sixteenth Corps, at the Battle of Nashville, Tennessee, December 15, 1864, from Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, January 14, 1865, p. 25 (Newberry Library)

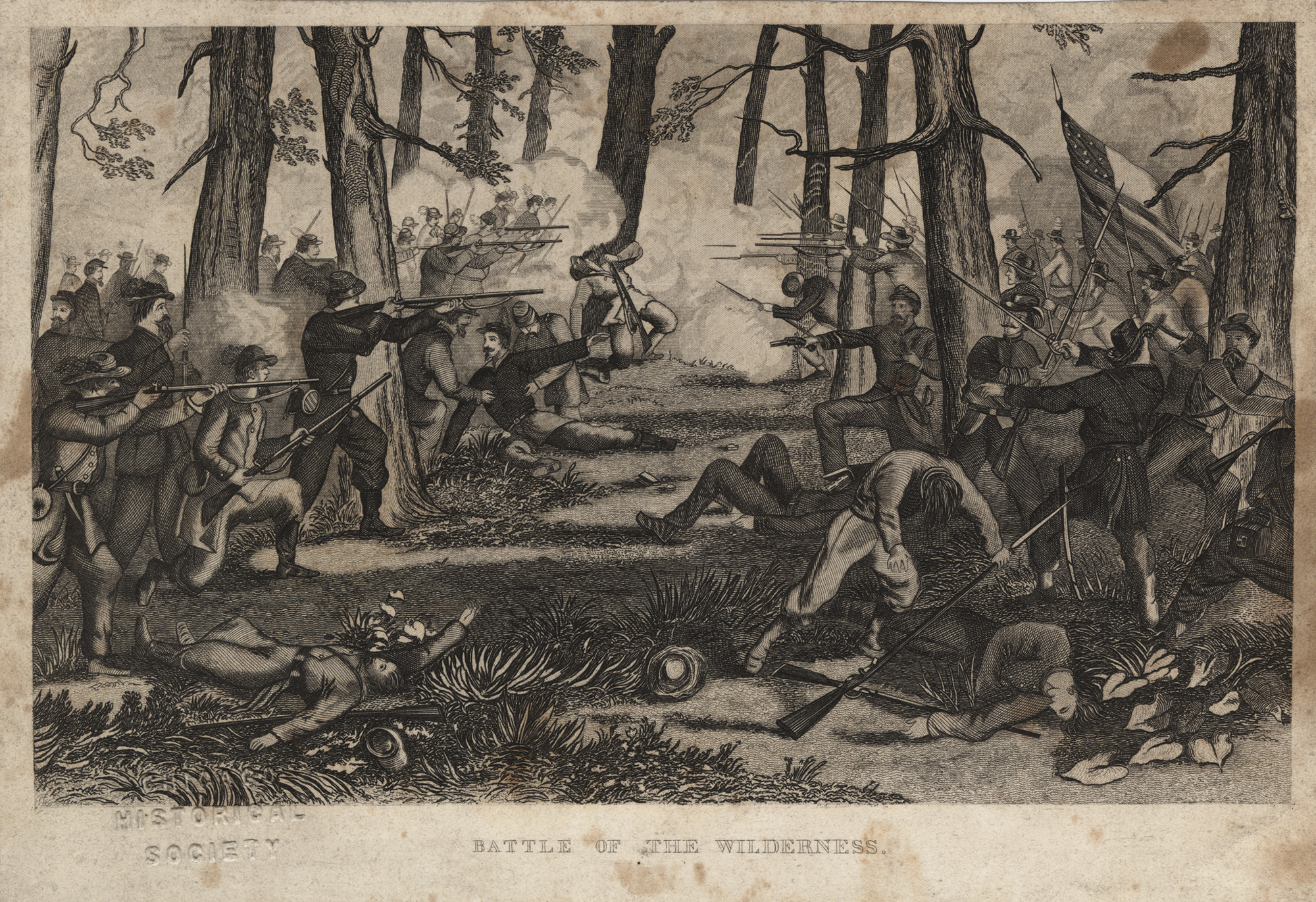

The Battle of Nashville was fought outside the city on December 15 and 16, 1863, resulting in a massive and decisive U.S. Army victory. Notably, the initial U.S. Army attack (not shown here) was led by two brigades of the 13th U.S. Colored Troops Infantry. The battle effectively destroyed the Confederate Army of Tennessee, its second largest force, and left the South weakened and vulnerable. George H. Ellsbury, Charge of the Third Brigade, First Division, Sixteenth Corps, at the Battle of Nashville, Tennessee, December 15, 1864, from Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, January 14, 1865, p. 25 (Newberry Library) The Confederate and U.S. Armies fought against each other for sixteen days in May of 1864 in “the Wilderness,” a thick forest of cedar and pine trees in northeastern Virginia. As depicted in this scene, the armies fought at close range, creating great clouds of smoke, dozens of small forest fires, and terrifying confusion as men struggled for position in the darkening gloom. Battle of the Wilderness, c. 1864, lithograph, 5 x 7 inches (Chicago History Museum)

The Confederate and U.S. Armies fought against each other for sixteen days in May of 1864 in “the Wilderness,” a thick forest of cedar and pine trees in northeastern Virginia. As depicted in this scene, the armies fought at close range, creating great clouds of smoke, dozens of small forest fires, and terrifying confusion as men struggled for position in the darkening gloom. Battle of the Wilderness, c. 1864, lithograph, 5 x 7 inches (Chicago History Museum) On December 13, 1862, the U.S. Army suffered one of its worst defeats at the Battle of Fredericksburg. In this scene, Confederate troops are firing at U.S. Army soldiers on the pontoon bridges over the Rappahannock River. This print, made more than twenty years later by the Chicago lithography company of Kurz & Allison, pays tribute to the brave men of the U.S. Army who fought in this battle. Battle of Fredericksburg, 1888, lithograph, Kurz & Allison, Art Publishers, 22 x 28 inches (Chicago History Museum)

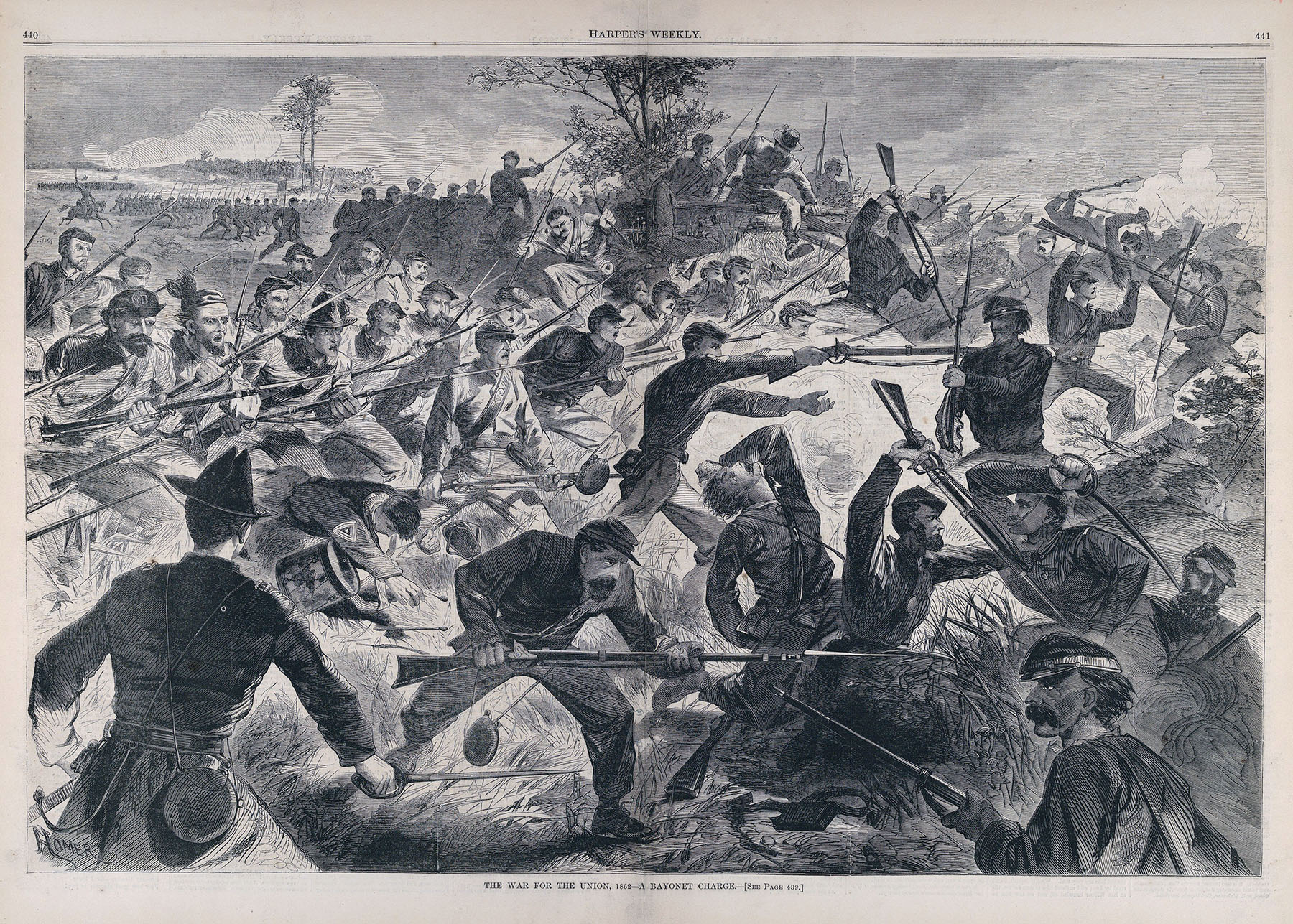

On December 13, 1862, the U.S. Army suffered one of its worst defeats at the Battle of Fredericksburg. In this scene, Confederate troops are firing at U.S. Army soldiers on the pontoon bridges over the Rappahannock River. This print, made more than twenty years later by the Chicago lithography company of Kurz & Allison, pays tribute to the brave men of the U.S. Army who fought in this battle. Battle of Fredericksburg, 1888, lithograph, Kurz & Allison, Art Publishers, 22 x 28 inches (Chicago History Museum) Sketches from special artists like Winslow Homer attempted to capture the violent fray of battle, as in his depiction of a bayonet charge during the Battle of Seven Pines in Virginia on May 31, 1862. It is unlikely that Homer was close enough to see this charge firsthand, relying instead on artistic conventions of portraying combat. After Winslow Homer, The War for the Union, 1862—A Bayonet Charge, wood engraving on paper, Harper's Weekly, July 12, 1862, 40.8 x 57.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Sketches from special artists like Winslow Homer attempted to capture the violent fray of battle, as in his depiction of a bayonet charge during the Battle of Seven Pines in Virginia on May 31, 1862. It is unlikely that Homer was close enough to see this charge firsthand, relying instead on artistic conventions of portraying combat. After Winslow Homer, The War for the Union, 1862—A Bayonet Charge, wood engraving on paper, Harper's Weekly, July 12, 1862, 40.8 x 57.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) There are very few photographs of Civil War battles in progress: camera emulsions were not sensitive enough at that point to capture people and objects in motion. One very rare exception is this photograph, taken by a Confederate named George Smith Cook in 1863, showing U.S. ironclad ships firing on a fort in Charleston Harbor. George Smith Cook, View from a parapet, Charleston Harbor, S.C., 1863, albumen print on card mount (Library of Congress)

There are very few photographs of Civil War battles in progress: camera emulsions were not sensitive enough at that point to capture people and objects in motion. One very rare exception is this photograph, taken by a Confederate named George Smith Cook in 1863, showing U.S. ironclad ships firing on a fort in Charleston Harbor. George Smith Cook, View from a parapet, Charleston Harbor, S.C., 1863, albumen print on card mount (Library of Congress) The U.S. Army’s victory at the Battle of Gettysburg in early July 1863 was a turning point in the Civil War, although it brought the highest death toll of any battle in the four-year conflict. In comparison to precedents of military victory scenes, this photograph unusually focuses on the horrors of death on the battlefield rather than a decisive moment of heroism or triumph. Timothy O’Sullivan, A Harvest of Death, 1863, albumen print, 17.2 × 22.5 cm, illustration in Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War, 1866 (Library of Congress)

The U.S. Army’s victory at the Battle of Gettysburg in early July 1863 was a turning point in the Civil War, although it brought the highest death toll of any battle in the four-year conflict. In comparison to precedents of military victory scenes, this photograph unusually focuses on the horrors of death on the battlefield rather than a decisive moment of heroism or triumph. Timothy O’Sullivan, A Harvest of Death, 1863, albumen print, 17.2 × 22.5 cm, illustration in Alexander Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War, 1866 (Library of Congress) Diné (Navajo) have a long history of weaving, but Diné weavers began producing rugs with the bright colors and patterns seen here in the second half of the 19th century as a result of their treatment—including imprisonment—by the U.S. government during the Civil War. Unknown Diné (Navajo) artist, Eyedazzler Blanket/Rug, c. 1885, wool, 71 x 54 inches (Denver Art Museum)

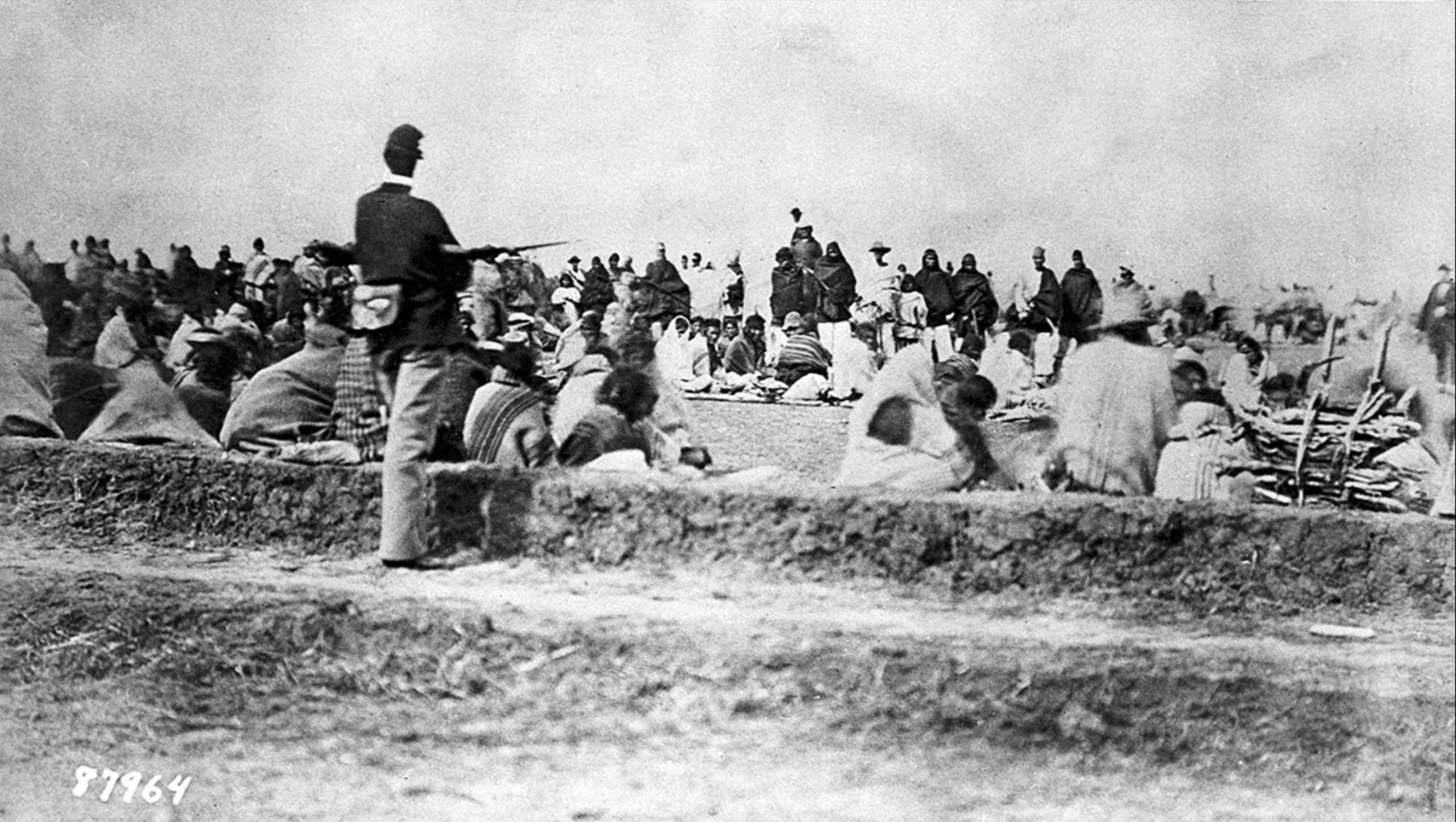

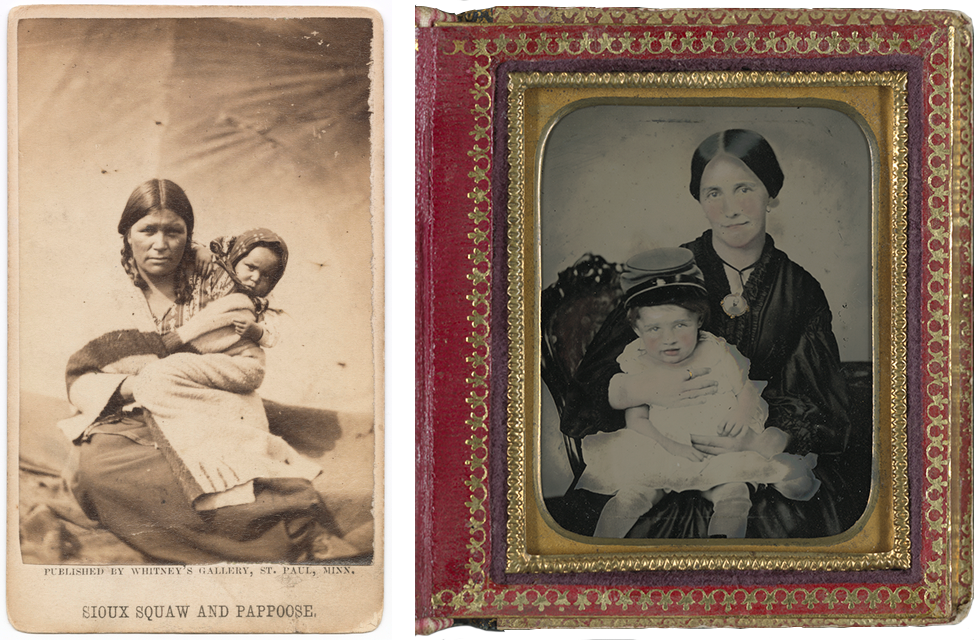

Diné (Navajo) have a long history of weaving, but Diné weavers began producing rugs with the bright colors and patterns seen here in the second half of the 19th century as a result of their treatment—including imprisonment—by the U.S. government during the Civil War. Unknown Diné (Navajo) artist, Eyedazzler Blanket/Rug, c. 1885, wool, 71 x 54 inches (Denver Art Museum) Between 1863 and 1866, the New Mexico Volunteers (temporary regiments of U.S. Army soldiers during the Civil War) forced 9,000 Diné to abandon their home centered around Canyon de Chelly in eastern Arizona and march some 400 miles to a concentration camp in Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. This picture depicts a group of Diné under guard at Fort Sumner, part of the Bosque Redondo reservation. Diné (Navajo) captives under guard, Fort Sumner, New Mexico, c. 1864–68 (New Mexico History Museum, photo: United States Army Signal Corps)

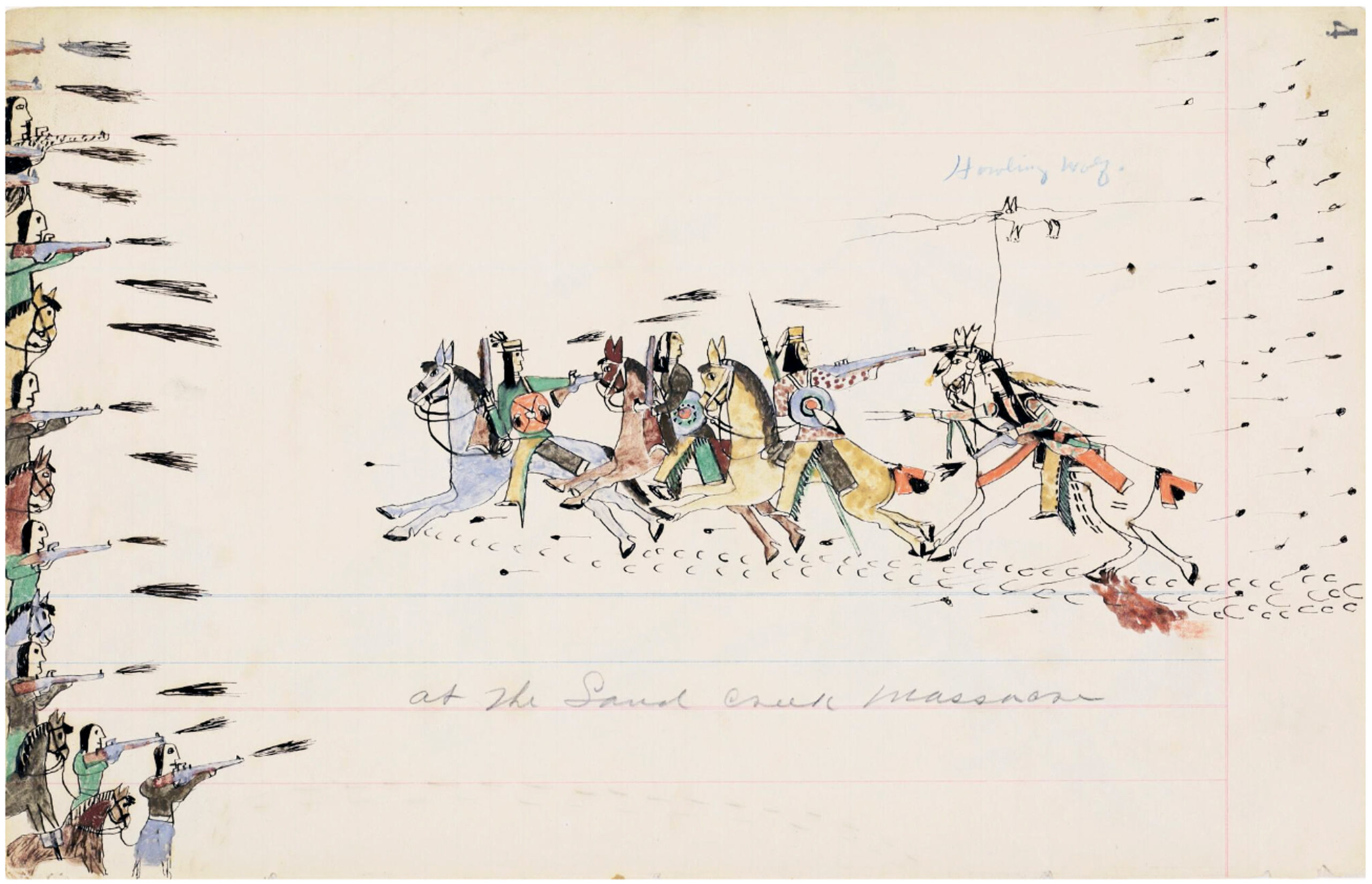

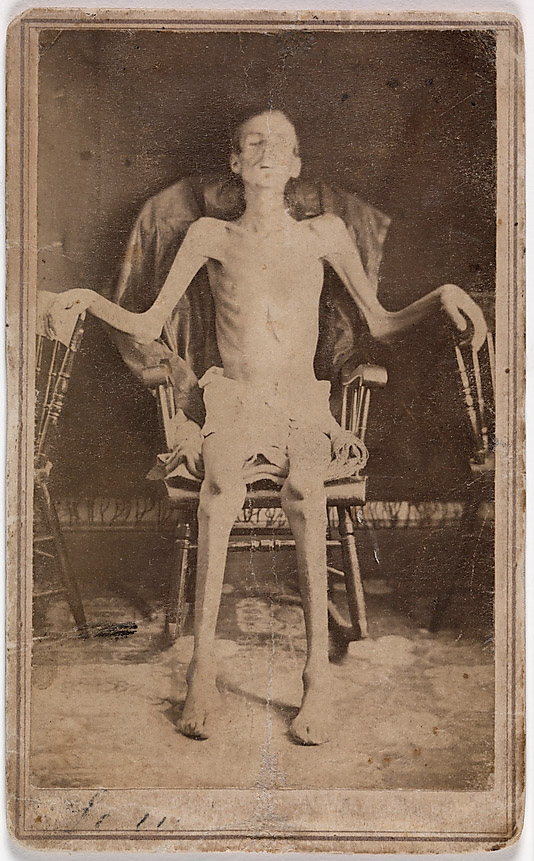

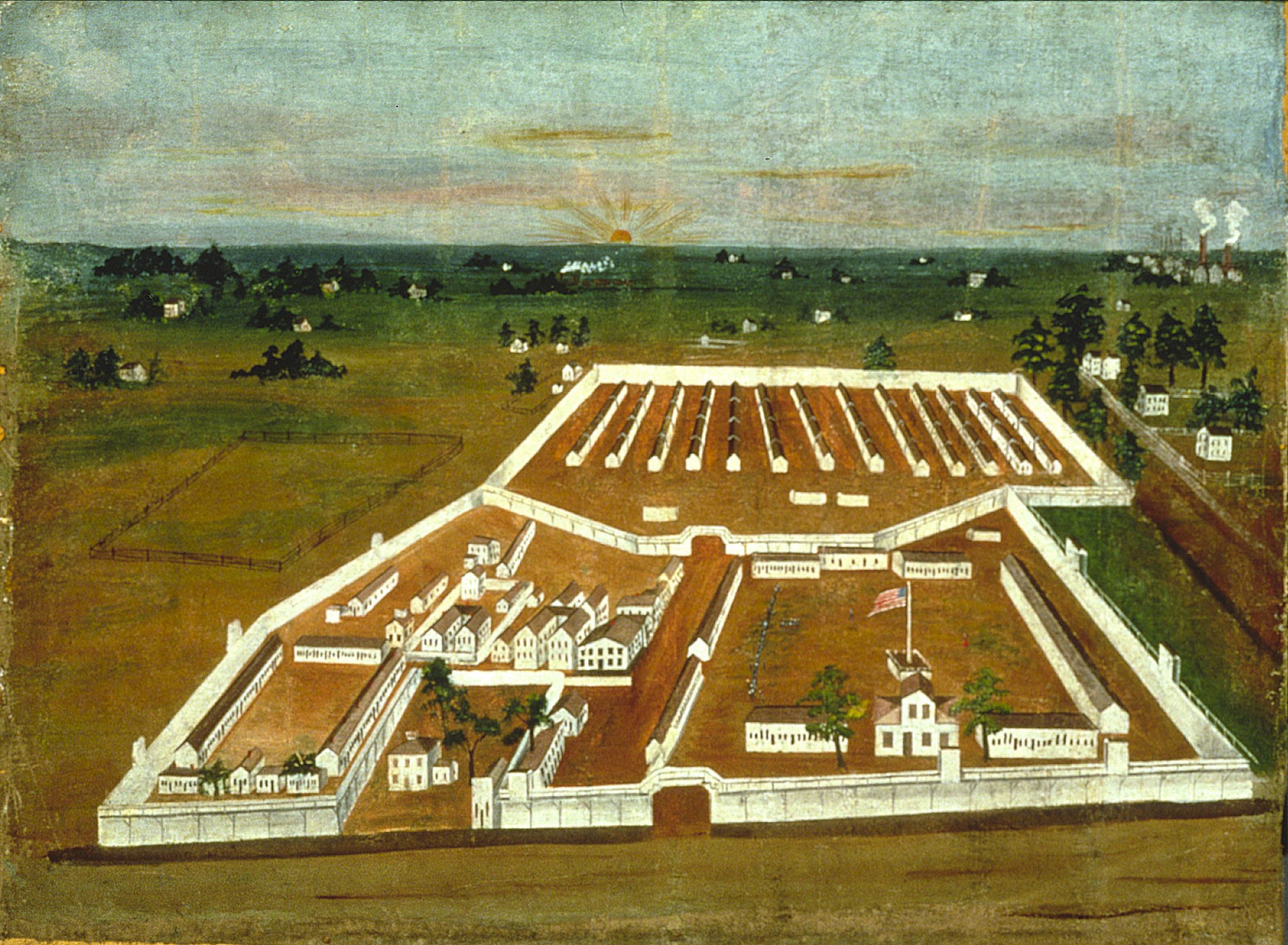

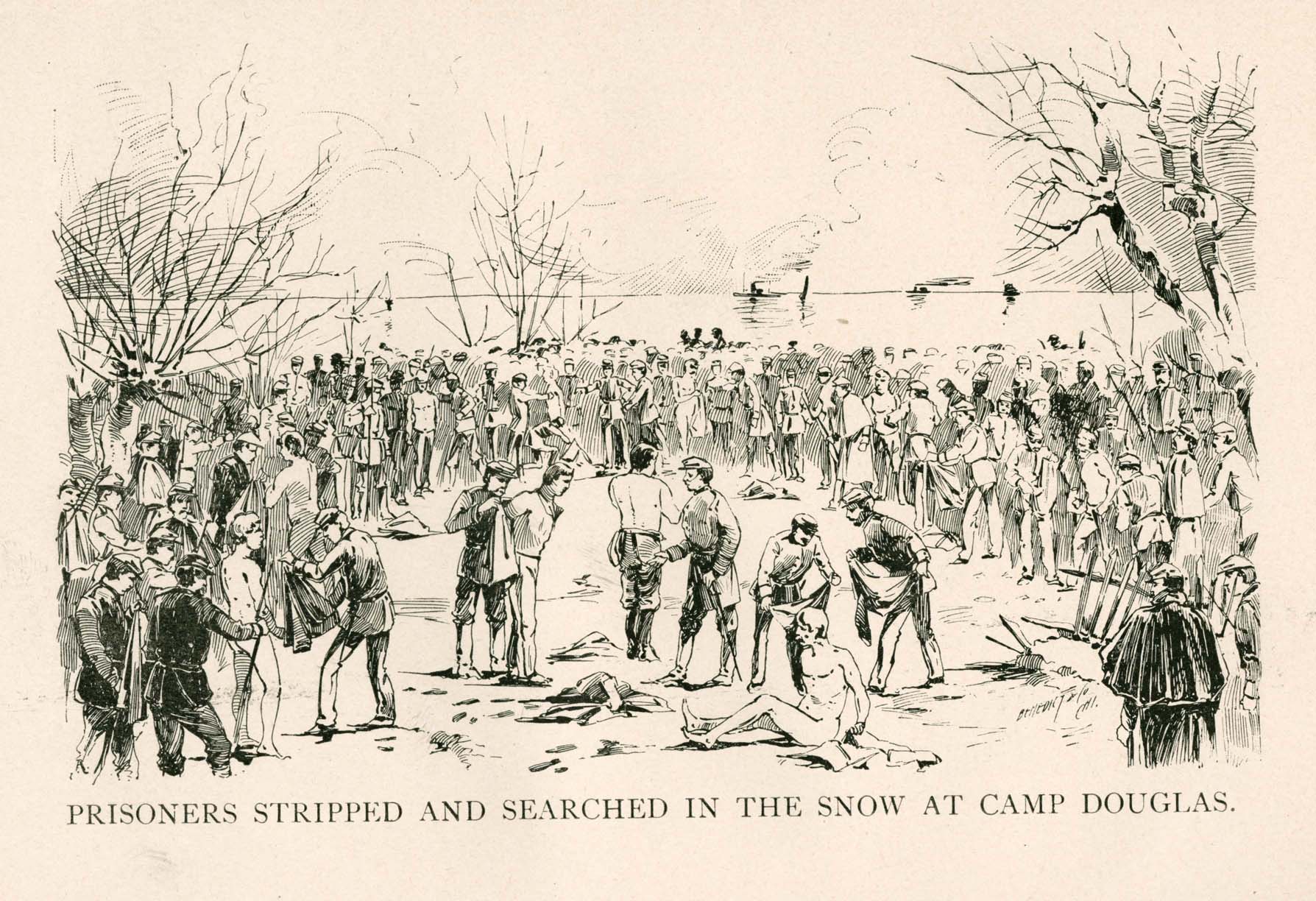

Between 1863 and 1866, the New Mexico Volunteers (temporary regiments of U.S. Army soldiers during the Civil War) forced 9,000 Diné to abandon their home centered around Canyon de Chelly in eastern Arizona and march some 400 miles to a concentration camp in Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. This picture depicts a group of Diné under guard at Fort Sumner, part of the Bosque Redondo reservation. Diné (Navajo) captives under guard, Fort Sumner, New Mexico, c. 1864–68 (New Mexico History Museum, photo: United States Army Signal Corps) The U.S. Civil War presented substantial dangers, including displacement, loss of sovereignty, and the loss of lands for Indigenous peoples in North America, even those who made peace with the U.S. Army. This ledger drawing records the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, when a Colorado militia attacked Cheyennes and Arapahos (who had negotiated peace and were flying an American flag and a white flag of truce above their camp). Ho-na-nist-to (Howling Wolf, Southern Cheyenne), At Sand Creek Massacre, 1874–75, pen, ink, and watercolor on ledger paper, 20 × 31.5 cm (Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College)