Unknown Diné (Navajo) artist, Eyedazzler Blanket/Rug, c. 1885, wool, 71 x 54 inches (Denver Art Museum)

The colors of this rug are striking: bold, saturated reds and deep-navy blues, in repeating patterns of diamonds, crosses, and American flags. It’s easy to see why this was called an “eyedazzler”—but less easy to see the unique circumstances that led Diné (Navajo) weavers to begin producing it in the second half of the 19th century. Diné people have a long history of weaving, using the wool of their Churro sheep. However, during the Civil War, the U.S. government interrupted Diné life and traditions, claiming that the Diné who did not move on to a reservation would be viewed as Confederate allies and therefore enemies.

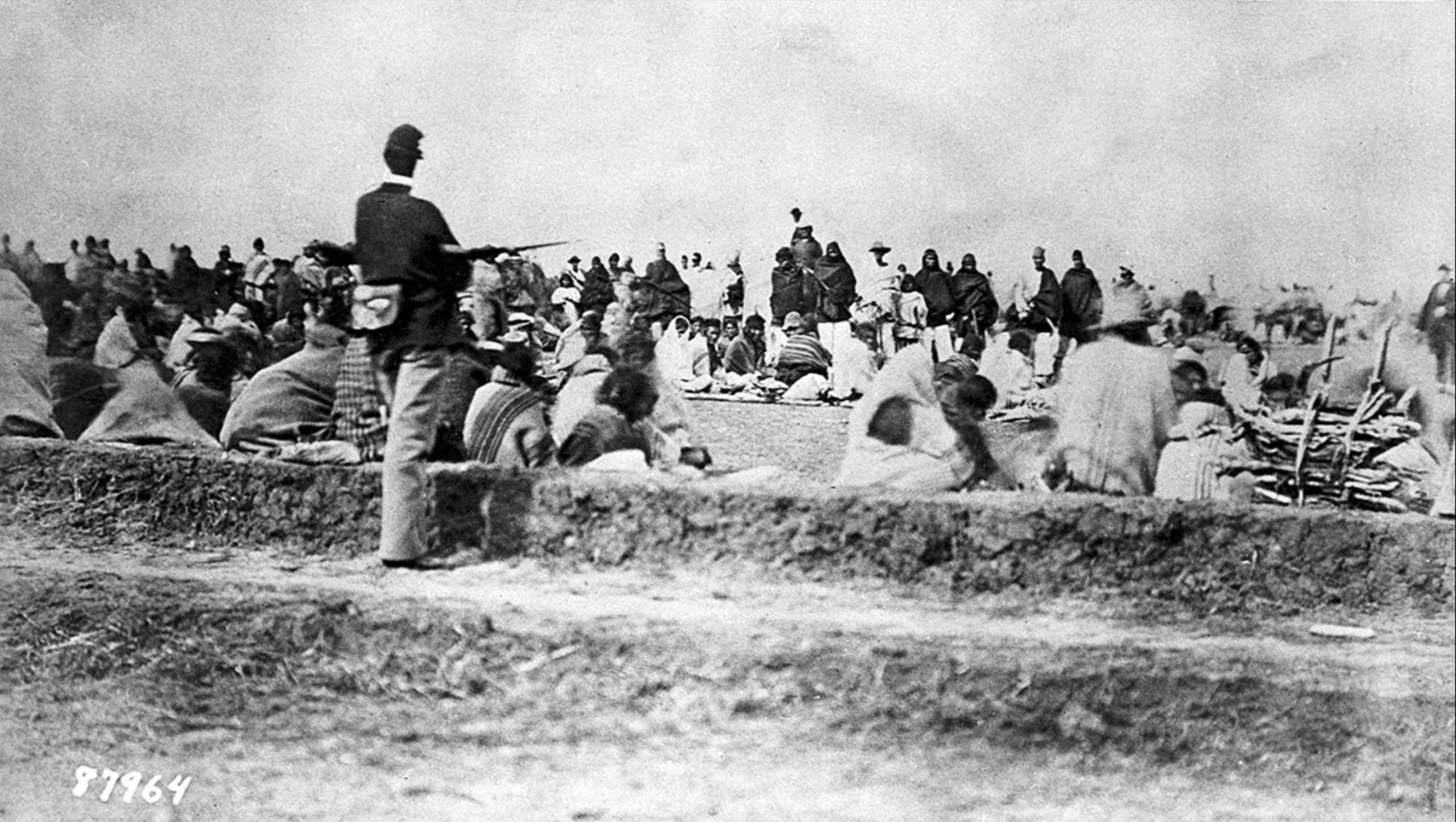

Diné (Navajo) captives under guard, Fort Sumner, New Mexico, c. 1864–68 (New Mexico History Museum, photo: United States Army Signal Corps)

Western states with U.S. Army regiments often employed them to suppress local Indigenous groups that were resisting the growing incursions into their territory (claiming that any resistance was tantamount to allying with the Confederates). Between 1863 and 1866, the New Mexico Volunteers forced 9,000 Diné to abandon their home centered around Canyon de Chelly in eastern Arizona and march some 400 miles to a concentration camp in Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. (More than 400 Mescalero Apaches were also imprisoned there). As many as 3,000 people died from exposure on the “Long Walk” to internment, or from disease at Bosque Redondo. Because the U.S. government had seized Diné land and livestock during the U.S. Civil War, when the Diné returned in 1868 to a reservation carved out of their traditional lands, they no longer had the sheep that had traditionally been their source of meat and wool.

Unknown Diné (Navajo) artist, Eyedazzler Blanket/Rug (detail), c. 1885, wool, 71 x 54 inches (Denver Art Museum)

The patterns and colors of this rug provide a testament to this history: the serrated diamond shapes echo those of Saltillo blankets, which Diné artists became familiar with when the U.S. government issued them during their forced march to and subsequent internment at Bosque Redondo. The eyedazzler’s wool yarn, often called “Germantown” because it was made in Germantown, Pennsylvania, got its bright colors from synthetic dyes, which imparted a broader range of colors than the natural dyes Diné weavers traditionally used. The U.S. government agreed to provide Germantown wool for weaving blankets and rugs as part of the terms of their peace treaty and annual annuity payments, and so Diné weavers began producing these eyedazzlers for sale—including the American flag symbol that might increase their appeal to non-Indigenous buyers. [1] This striking rug is not just a work of art but also a testament to the forced displacement, violence, hardship, resilience, and transformation that the Diné underwent during and after the Civil War.

The Diné were not the only people who experienced profound change due to displacement during the war. Although we often think of the Civil War in terms of soldiers on battlefields and families on the homefront, there were other sites and lived experiences that have not traditionally received as much attention. The Civil War prompted people to migrate, both voluntarily (for example, the enslaved people who emancipated themselves) and involuntarily (like the Diné, Apaches, and other Indigenous groups that U.S. officials interned during the war). Prisoners, refugees, and internees may have been at some distance from the battlefield, but their experiences were central to the war’s core issues: race, citizenship, and the meaning of freedom.

Eastman Johnson, A Ride for Liberty — The Fugitive Slaves, c. 1862, oil on paper board, 55.8 x 66.4 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Contrabands, refugees, and self-emancipation

Displacement had always been part of the experience of slavery: Africans had been kidnapped and forced to cross the ocean in the Atlantic slave trade, and in the 19th century, United States enslavers sold Black men, women, and children whenever it suited their interests, forcing individuals to move to new locations and separating families. Freedom, too, meant movement: enslaved people emancipated themselves by running away to free territory. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, and the U.S. Army began to move through the South, enslaved people quickly realized that “free territory” might be closer than ever before: behind army lines.

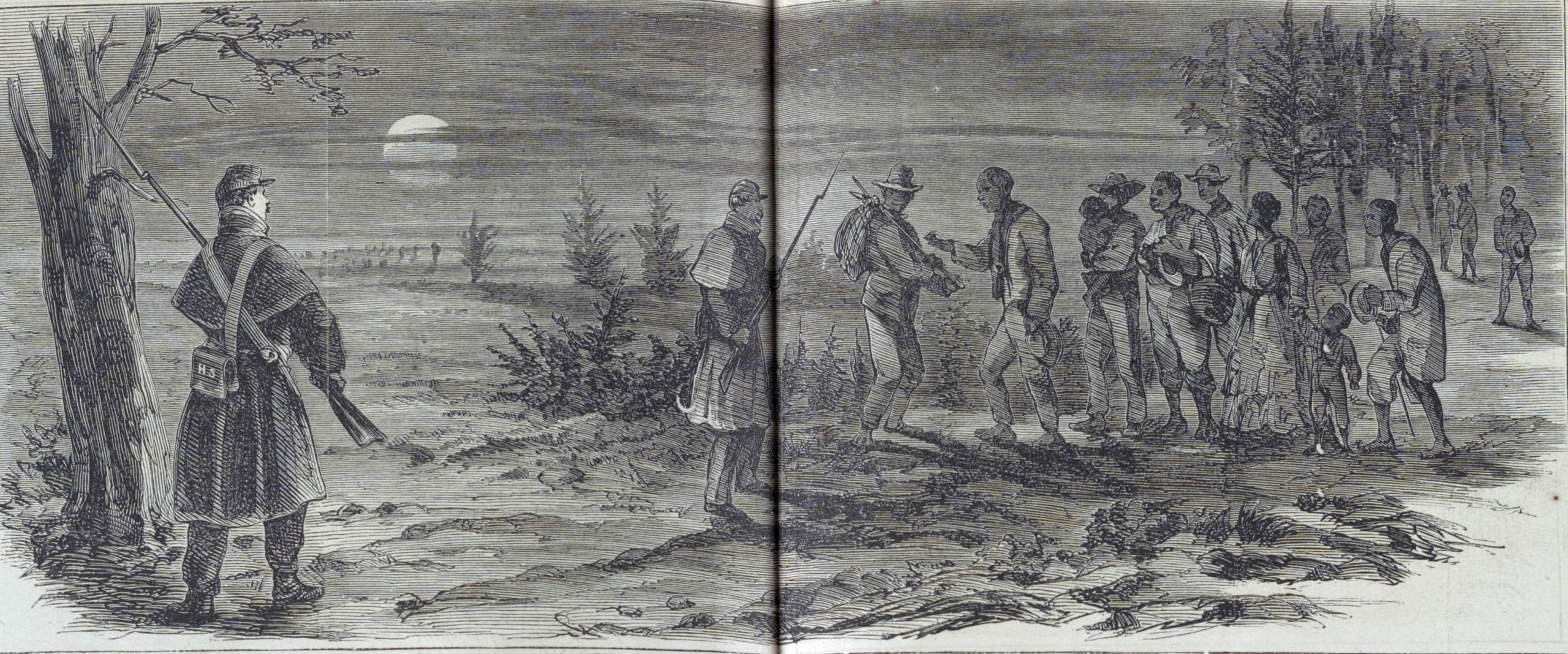

Refugees meeting U.S. Army officers at night and requesting asylum (detail), “Stampede among the Negroes in Virginia—their arrival at Fortress Monroe / from sketches by our Special Artist in Fortress Monroe,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 8, 1861, pp. 56–57, wood engraving, 40.4 x 54.3 cm (Library of Congress)

But escape, as always, was a gamble—especially when the official U.S. government policy was not to interfere with the institution of slavery, to return to their enslavers any self-emancipated Black men or women who arrived at U.S. Army camps. The proximity of the U.S. Army made the journey to freedom shorter, but it also meant that enslavers were close at hand, waiting for an opportunity to reclaim their “property.” Refugees displayed incredible bravery and hope when they arrived at U.S. Army lines with nothing but a willingness to do whatever it took to survive.

Some of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s generals defied the order to return enslaved people, however. U.S. General John C. Frémont declared he would emancipate all enslaved people belonging to rebels in Missouri in August 1861, an edict that Lincoln forced him to rescind in order to pacify enslavers in states that had not seceded from the United States.

That same year at Fort Monroe, Virginia (which U.S. forces managed to retain despite Virginia having voted to secede), U.S. Army General Benjamin Butler refused to return self-emancipated people who arrived at his camp to their enslavers. Instead, he claimed them as “contraband” of war—a designation that allowed his army to retain them (since contraband refers to captured enemy property, Butler turned the enslavers’ own arguments, that the enslaved were property, against them). The term contraband became widely used to refer to people who escaped from slavery, but today scholars use the term refugee, which better describes their journey toward freedom. Enslaved people flocked to Fort Monroe, and although the designation of “contraband” did not guarantee their freedom, it did, in the words of historian Amy Murrell Taylor, “open space for enslaved people inside the Union army’s lines, physical spaces in which to live beyond their owners’ reach and to begin imagining the future.” [2]

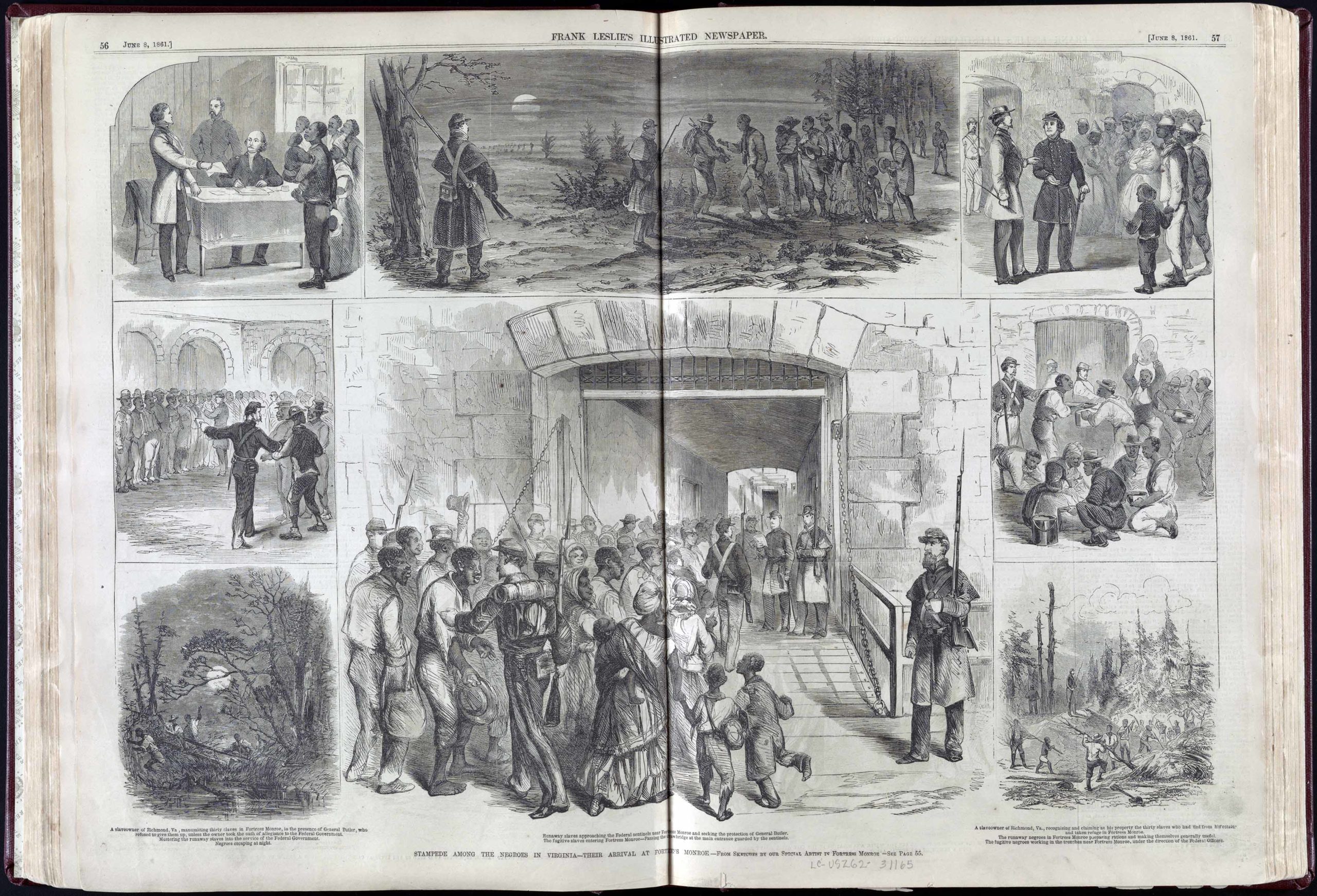

“Stampede among the Negroes in Virginia—their arrival at Fortress Monroe / from sketches by our Special Artist in Fortress Monroe,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 8, 1861, pp. 56–57, wood engraving, 40.4 x 54.3 cm (Library of Congress)

In the first months of the Civil War, opinions in the North were divided as to whether the conflict ought to be a war to liberate enslaved people or remain confined to the more narrow aim of preserving the Union. This two-page spread printed in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in 1861 reflects northern ambiguity toward emancipation. A large central image depicts refugees entering the drawbridge at Fort Monroe in Virginia, surrounded by seven vignettes depicting the journeys of refugees. Said to be based on sketches by the newspaper’s special artist (although it doesn’t seem likely that he would have personally witnessed refugees making a daring nighttime escape) the vignettes show (clockwise from bottom left):

1. refugees crossing a river by moonlight

2. white U.S. Army officers mustering refugees into work detail

3. an enslaver manumitting the refugees he had formerly owned rather than swearing an oath of allegiance to the U.S. government

4. a group of refugees meeting U.S. Army officers at night and requesting asylum

5. a second enslaver identifying refugees who had come to the fort as his property and asking a U.S. officer to remand them

6. a group of refugees preparing and receiving rations from the U.S. Army and

7. refugee men working in the trenches under the direction of white U.S. officers.

The artist alternately depicts refugees as sympathetic (with frightened men, women, and children appealing for protection) and grotesque (with exaggerated, racial stereotypes of Black figures, clearly contrasted against the upright white U.S. soldiers). The title of the image reports that the refugees are on a “stampede,” a term commonly used to describe the movement of animals, which dehumanizes the refugees. Although the overall message seems to praise the U.S. Army for taking in refugees, it also suggests that their value is (as one of the captions suggests) in “making themselves generally useful” to the U.S. Army by doing the bidding of its officers rather than enemy officers. [3]

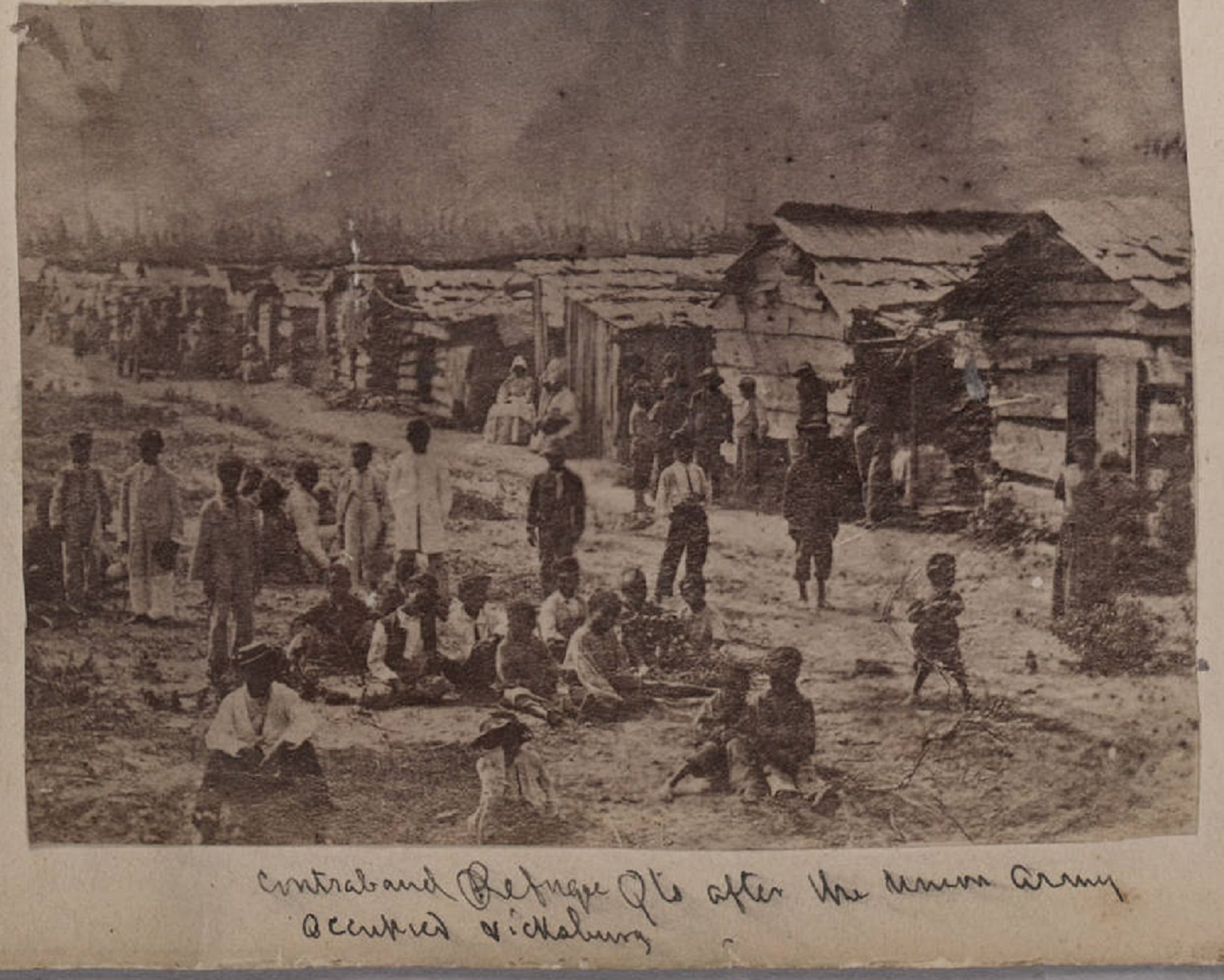

Contraband Refugee Quarters after the Union Army occupied Vicksburg, 1863–65 (Huntington Library)

Whether or not white northerners supported abolition had no bearing on the actions of enslaved people who were determined to self-emancipate. Historians estimate that one million enslaved people freed themselves between 1861 and 1865, and approximately 500,000 lived in refugee camps (constructed by the U.S. Army or by refugees themselves) as they sought a new life. [4]

There were nearly 300 of these settlements, and the U.S. War Department stepped in to manage refugee affairs, a precursor to the Freedman’s Bureau that would assist formerly enslaved people starting in 1865. [5] The photograph above, likely cut from a carte-de-visite, shows refugees in one such camp at Helena, Arkansas. In the foreground, a group of children sits on the ground, looking at the camera, with some more young people standing behind them wearing similar coats (possibly provided by one of the many northern aid societies that sent food, clothing, medicine, doctors, and teachers to the refugee camps). [6] In the middle ground stands a row of shelters, which look to have been built by the refugees themselves with available materials. Adults sit and stand in front of them. The road in front of the houses is muddy, indicating the recent construction and soggy conditions near the Mississippi River, where this camp was located.

Although conditions in the camps were difficult—scant rations, little medical care, and poor sanitation—they served as important hubs for newly free Black people during and after the war. They brought Black people together in a community apart from life on the plantation. Many camps were located near bodies of water to facilitate transportation as refugees searched for the family members whom enslavers had separated from them before the war. Refugee camps were also central points for recruiting men to serve in the U.S. Army.

In 1862, the U.S. government authorized both the deployment of Black laborers and the enlistment of Black soldiers in new federal regiments called the United States Colored Troops, or USCT. Men who self-emancipated (in addition to free Black men from the North) were eager to join these regiments, even though they were segregated from white soldiers, led by white officers, and paid less than white men until nearly the end of the war. Many viewed military service as an opportunity to fight for the enduring freedom of Black Americans and to make a claim to citizenship as men who fought for their country.

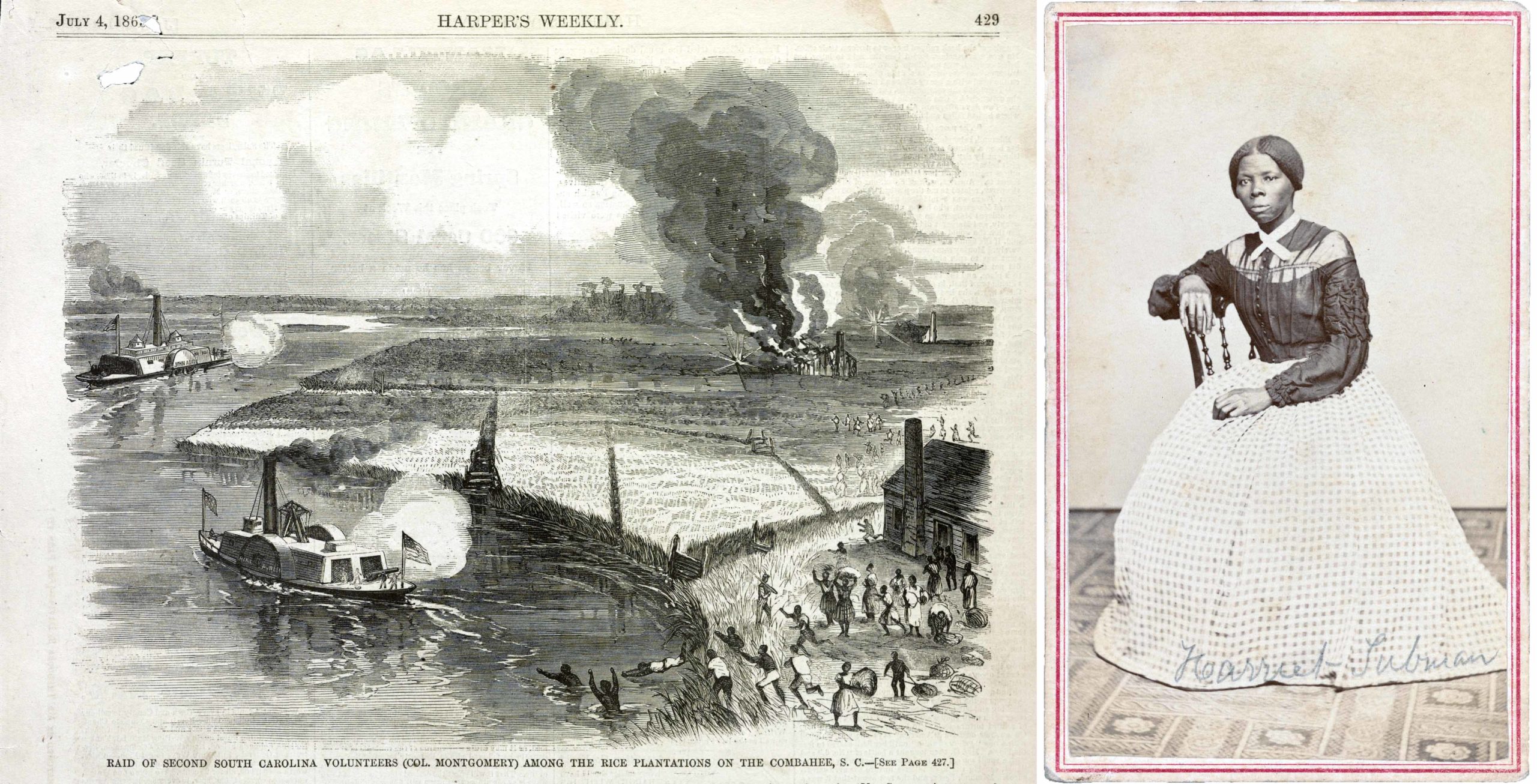

Left: “Raid Of Second South Carolina Volunteers (Col. Montgomery) Among The Rice Plantations On The Combahee, S.C.,” Harper’s Weekly, July 4, 1863, p. 429, wood engraving, 27.6 x 39.5 cm (Library of Congress); right: Benjamin F. Powelson, Portrait of Harriet Tubman, c. 1868–69, albumen carte-de-visite, 10 x 6 cm (Library of Congress)

Women were eager to help the U.S. Army as well. Most often they were referred to as “laundresses,” though we know that many did much more than that. Refugee women also cooked to help sustain U.S. soldiers, and some served as spies. Harriet Tubman, who had emancipated herself in 1849, became the first woman to lead a major military operation in the United States when she led 150 members of the U.S. 2nd South Carolina Volunteers—a Black regiment with many soldiers drawn from the ranks of self-emancipated men—in a raid on Combahee Ferry in South Carolina. Using three U.S. gunboats, Tubman and the soldiers rescued at least 700 enslaved Black people on the night of June 1, 1863.

Samuel Willard Bridgham, Portrait of Susie King Taylor, 1880s, daguerreotype (Stephen Restelli, private collection)

Susie King Taylor, who was born into slavery in Georgia, and self-emancipated in 1862, performed gun maintenance and worked as a nurse and a teacher. [7] She learned how to read and write as a child in clandestine schools thanks to her grandmother (teaching reading or writing to free or enslaved Blacks had been illegal in Georgia since the 1770s). [8] Taylor later published a memoir of her experiences in the war, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp. In the photograph above, Taylor is seated in profile but her head is turned to look at us. She is enveloped in a voluminous skirt and tight-fitting jacket. The formality of the pose contrasts with the lush foliage behind her. The growing presence of women in public life during the Civil War coincided with the rise of relatively inexpensive portrait photography. However, where most photographs of the period depict their subjects in the studio, this one is set, unusually, outdoors.

Prisoners of war

Prisoners of war from both the United States and the Confederacy comprised another large group of displaced persons. Over the course of the conflict, more than 400,000 men were imprisoned, often in horrific conditions. For the first two years of the war, the two armies exchanged prisoners according to a normal parole system. But prisoner exchanges broke down in 1863 after the U.S. Army enlisted Black soldiers; Confederates refused to return any Black soldiers, instead insisting on either enslaving them or executing them immediately. The U.S. government held firm that all soldiers were to be treated the same in prisoner exchanges and that it would not exchange white soldiers while permitting Black soldiers to be killed or enslaved.

Andrew Jackson Riddle, Andersonville Prison, Georgia. South-west view of the stockade Showing the dead line, August 17, 1864, salted paper print, 11 x 14 cm (Library of Congress)

And so from 1863 through early 1865 prisoners of war arrived, and kept arriving, at camps that were not designed for so many men to stay for such a long time. Both U.S. prisons and Confederate prisons were hellish places for soldiers, often lacking adequate food, shelter, and sanitation. Unable to feed and clothe its own soldiers, the Confederacy could hardly spare resources to supply prisoners’ needs. As the photograph of Andersonville Prison taken by Georgia photographer Andrew Jackson Riddle shows, U.S. soldiers who languished in Confederate prisons had to make their own improvised shelters. Starvation and disease ravaged the camp. In the summer of 1864 more than 100 men died per day in Andersonville, and nearly a third of its 45,000 inhabitants perished during the 18 months it operated. [9]

J. W. Jones, Emaciated Union Soldier Liberated from Andersonville Prison, 1860s, 1865, albumen silver print from glass negative, 9 x 5.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The release of U.S. soldiers from Confederate prison camps who were starving and often sick or injured occasioned an outcry among northerners who were shocked by men who had become living skeletons. Photographs of U.S. soldiers released from Belle Isle prison in Richmond were reproduced in illustrated newspapers in 1864 and led to calls for retaliation against the Confederate prisoners then held in U.S. camps. The photograph, taken in 1865, documents the horror wrought by starvation at Andersonville Prison, Georgia. This emaciated former prisoner is starkly contrasted against signifiers of peacetime civilian life. He is seated on a rocking chair with a carpet under his feet. How prisoners were treated in both northern and southern prisons remained a point of contention in U.S. politics and culture after the war. Republicans used these images to wave the bloody shirt in late 19th-century elections, and proponents of the Lost Cause were quick to claim that northern prisons were nearly as bad (but had received less coverage in northern newspapers).

Displacement and internment of Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples in North America did not escape violence of the U.S. Civil War even though much of the Great Plains, Great Basin, and Southwest was still under Indigenous control. Both the United States and the Confederacy recruited Indigenous nations and tribes as allies and Indigenous men as soldiers; about 3,500 Indigenous men served in the U.S. Army, and at least twice that many served in the Confederate army. As in the earlier Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution, Indigenous nations, tribes, and bands split their allegiances for a number of reasons: some practiced slavery, while others despised it; some saw the Confederate government as a welcome alternative to the U.S. government they had myriad reasons to distrust, while others hoped their service might lead the U.S. government to treat them fairly. For Indigenous peoples, participation in the Civil War presented opportunities to win concessions or land guarantees from the dueling governments in the east, and in some cases to use the conflict as a way to gain power within their own governments. But the war also presented substantial dangers, including displacement, loss of sovereignty, and the loss of lands.

The dangers proved to be more numerous than the opportunities. The Civil War intensified population pressures in Indian Territory (where the U.S. government had forced Indigenous peoples from the eastern part of the continent to migrate after U.S. president Andrew Jackson signed the 1830 Indian Removal Act). During the Civil War, Lincoln’s Republican Party made good on many of its campaign promises to white voters about securing the West as a place for “free labor” and “free men” by authorizing the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railway Act, both of which appropriated Indigenous lands and greatly accelerated the migration of non-Indigenous people to the West.

The U.S. Army classified any Indigenous people who did not completely cooperate with its political and military objectives during the Civil War as enemies sympathetic with the Confederacy, and relentlessly pursued the internment or extinction of such groups. Like the Diné and Apaches who were forced into the Bosque Redondo concentration camp, the U.S. Army forced more than 1,700 Santee Sioux to leave their homes in Minnesota after the Dakota War of 1862 and march over 100 miles to be held in a concentration camp. Shortly afterward, the U.S. government seized their historical lands in Minnesota and forced the Santee Sioux to move onto a distant reservation.

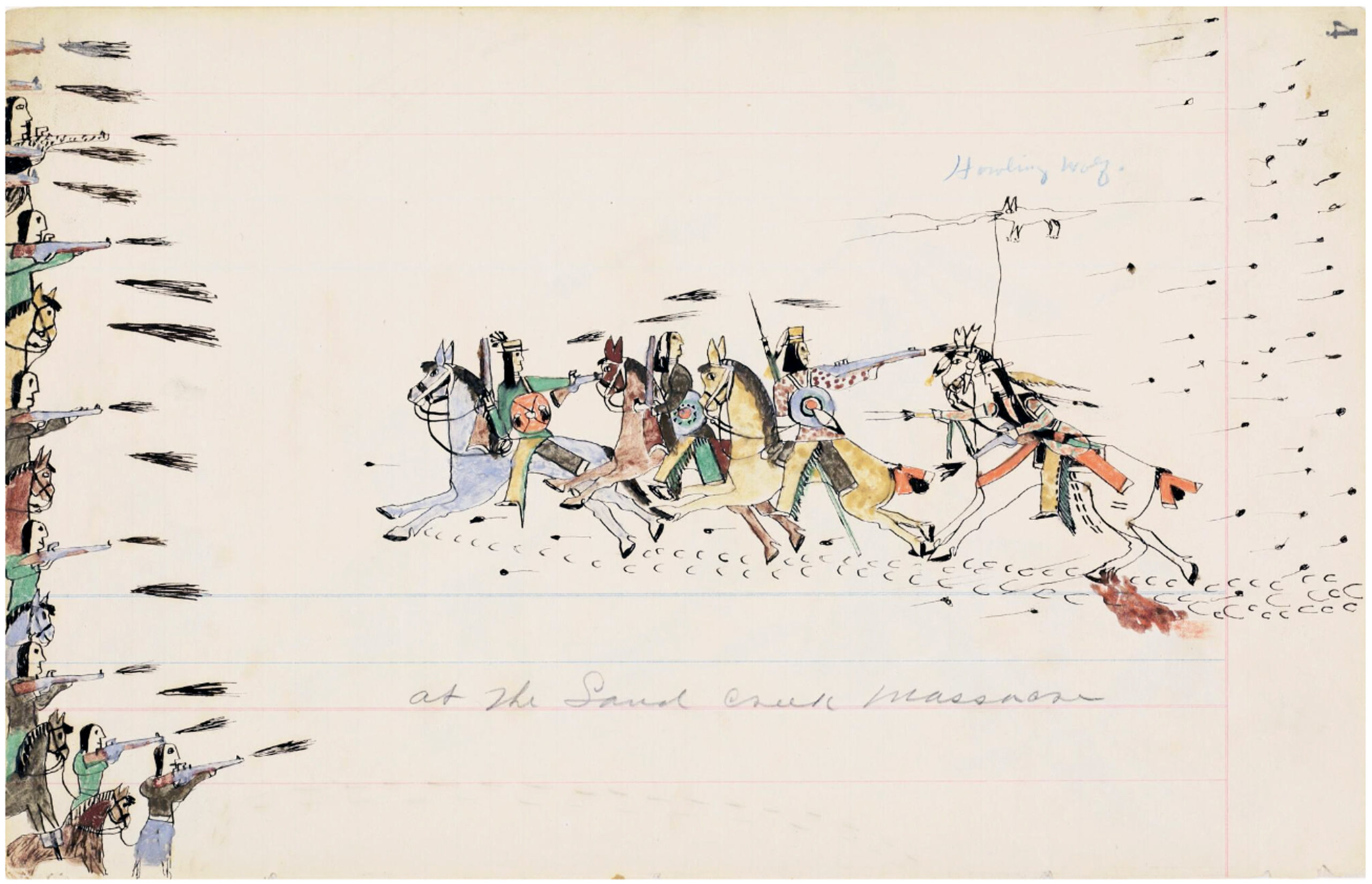

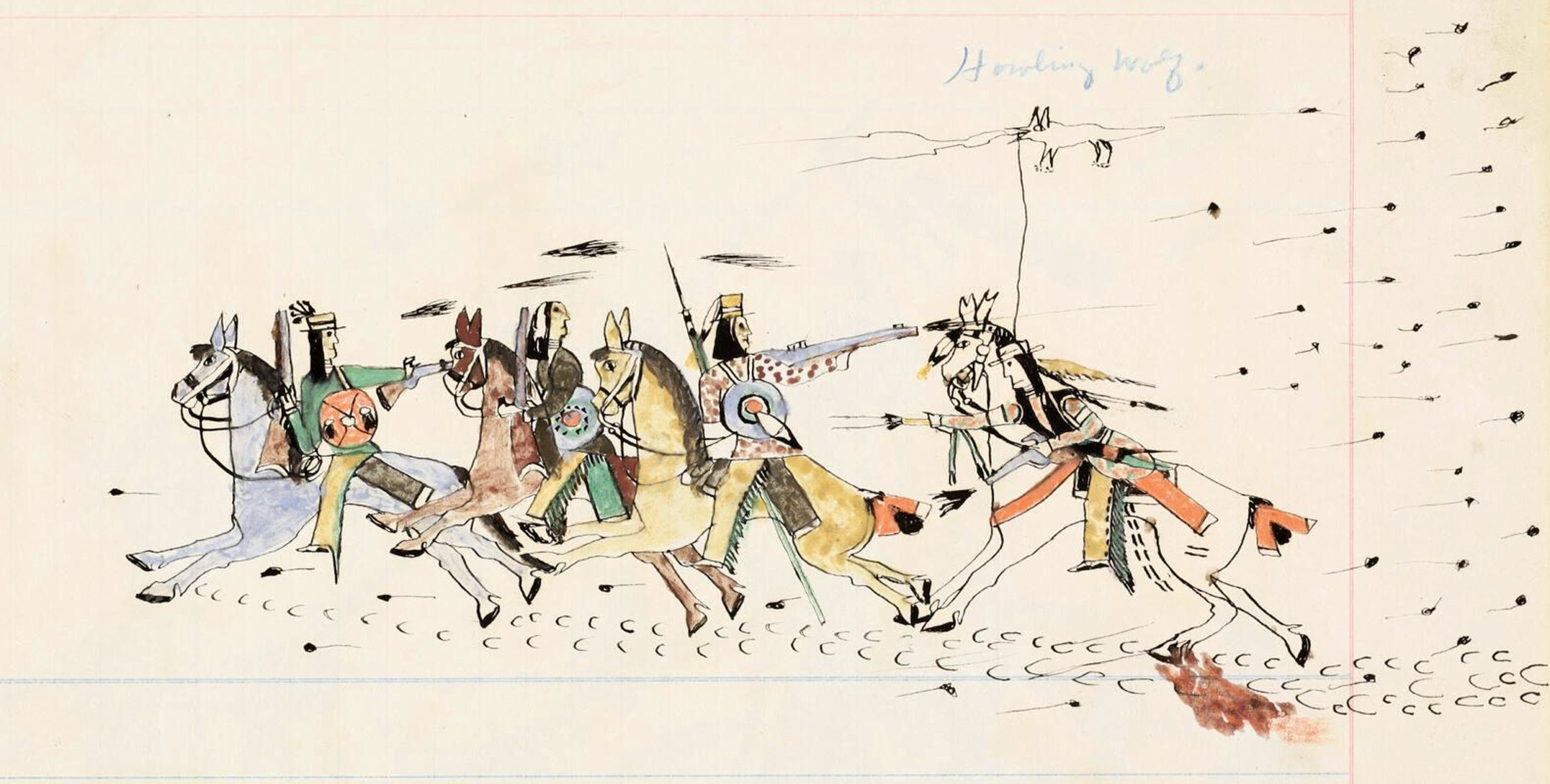

Ho-na-nist-to (Howling Wolf), Southern Tsétsêhéstâhese/Só’taeo’o (Cheyenne), At Sand Creek Massacre (1864), c. 1874–75, pen, ink, and watercolor on ledger paper, 20 x 31.5 cm (Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College)

Even those people who made peace with the U.S. Army were subject to violence. This ledger drawing was created by Ho-na-nist-to (Howling Wolf, Southern Cheyenne), who one historian refers to as “arguably the single most important Plains artist who worked on paper during the late nineteenth century.” [10] It records an event in 1864, when a Colorado militia attacked Cheyennes and Arapahos (who had negotiated peace with the U.S. Army and were flying an American flag and a white flag of truce above their camp). In the drawing, we see the U.S. soldiers and their horses along the left edge firing their weapons as bullets fly past the Cheyenne on horseback who ride toward them. Howling Wolf is the last figure on the right, shown here actively defending his camp (as he actually did during the conflict). Above him is a howling wolf and his name written in blue, important reminders of the power invested in naming. They are also reminders to anyone who might see them of his role in this history. He shoots at the army while his companions look back toward an enemy approaching from the rear. U.S. soldiers killed at least 200 Cheyenne and Arapaho men, women, and children at what became known as the Sand Creek Massacre.

Ho-na-nist-to (Howling Wolf), Southern Tsétsêhéstâhese/Só’taeo’o (Cheyenne), At Sand Creek Massacre (1864) (detail), c. 1874–75, pen, ink, and watercolor on ledger paper, 20 x 31.5 cm (Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College)

Colonel John M. Chivington, who led the attack, was initially hailed as a hero, but members of the U.S. military who had refused to participate in the massacre alerted their superiors, and Congress investigated the incident. Although the U.S. government found Chivington guilty and promised reparations, the Cheyennes and Arapahos were nevertheless driven onto reservations in Oklahoma (and the reparations were never paid). It was only after the Southern Cheyenne surrendered to the U.S. government and Ho-na-nist-to was imprisoned at Fort Marion, Florida, that he recounted his experiences in ledger drawings.

Experiences of displacement and incarceration

The experiences of people on the “margins” of the Civil War—in prison camps, in refugee camps, in concentration camps—can be more difficult to visualize than some Civil War experiences. These were often the people who had the fewest resources and often the least attention from their contemporaries. They rarely had the opportunity to control how they were represented in images. Yet careful attention to the visual and material culture that survives offers access to their wartime experiences as part of the war’s broader struggles: for freedom, recognition, and citizenship beyond the battlefield.

Notes:

[1] See Eyedazzler Blanket/Rug at the Denver Art Museum.

[2] Amy Murrell Taylor, Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018), p. 4.

[3] For an analysis of racial stereotypes of escaped slaves in Harper’s Weekly and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper during the Civil War, see Aston Gonzalez, “Stolen Looks, People Unbound: Picturing Contraband People during the Civil War,” Slavery & Abolition 40, no. 1 (2019): pp. 28–60.

[4] Thavolia Glymph, “Noncombatant Military Laborers in the Civil War,” OAH Magazine of History 26, no. 2 (April 2012): pp. 25–29.

[5] Taylor, Embattled Freedom, p. 6.

[6] Ryan Jordan, “Contraband Camps aka: Slave Refugee Camps,” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, Central Arkansas Library System, 2019.

[7] For more on women’s service see Taylor, Embattled Freedom, pp. 126–30. For more on Susie King Taylor, see this story map from the Library of Congress, and read Reminiscences of My Life in Camp online.

[8] Christopher M. Span, “Learning in Spite of Opposition: African Americans and Their History of Educational Exclusion in Antebellum America,” Counterpoints 131 (2005), p. 27.

[9] Evan A. Kutzler, Living by Inches: The Smells, Sounds, Tastes, and Feeling of Captivity in Civil War Prisons (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

[10] Joyce M. Szabo, “Howling Wolf (1849–1927),” Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, University of Nebraska—Lincoln, 2011.

Additional resources

The Long Walk from the National Museum of the American Indian

Peter John Brownlee et. al., Home Front: Daily Life in the Civil War North (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).

The Contraband Historical Society

Learn more about Bosque Redondo and its historic site

Abigail Cooper, “‘Away I Goin’ to Find My Mamma’: Self-Emancipation, Migration, and Kinship in Refugee Camps in the Civil War Era,” Journal of African American Life and History 102, no. 4 (Fall 2017): pp. 444–467.