Winslow Homer, Rainy Day in Camp, 1871, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 91.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Winslow Homer was 25 years old when he set off from New York City to join the U.S. Army in 1861 at the start of the U.S. Civil War. Like most young men going to war that year, he was eager to see action; unlike most, he was not there to fight but to draw. A special artist correspondent for Harper’s Weekly magazine, Homer sketched what he saw of soldiers’ lives while he was embedded with the army in Virginia: men camping, eating, fighting, ailing, longing for home. He mailed his sketches back to the magazine’s offices in the city, where engravers would quickly transform them into illustrations of the war for circulation among northern audiences.

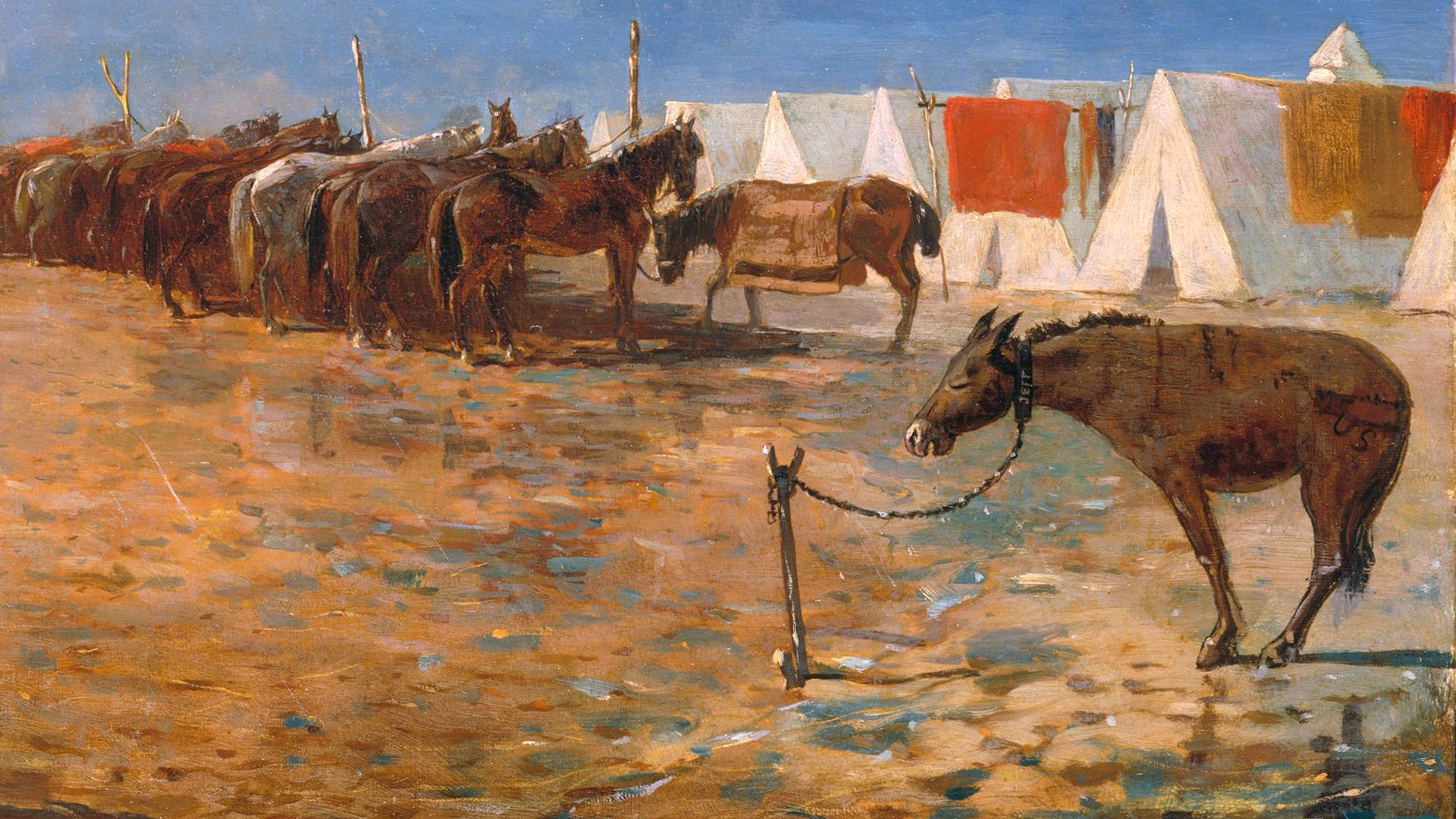

Winslow Homer, Rainy Day in Camp (detail), 1871, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 91.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

During and after the war, Homer also turned his sketches into finished paintings, like Rainy Day in Camp. Here, Homer captures some of the less romantic aspects of a soldier’s life: five white men, pelted by rain and surrounded by mud, crowded around a cookfire in muted misery. Behind them, a line of horses stretches to the horizon, a covered wagon is leaning in worrisome fashion, and a scattering of cross-like stands for tack at the far left reference make-shift camp graveyards.

Winslow Homer, Rainy Day in Camp (detail), 1871, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 91.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

At right, a mule named “Jeff” (his name is scrawled on his collar) pulls peevishly at his restraints; his moniker is a sarcastic insult to the President of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis. But the soldiers at the center of the canvas are just as stuck as Jeff the mule: stuck in the rain, stuck in the mud, and stuck in the army. If any of these men had cherished romantic ideas about a soldier’s life, days like this must have thrown cold water on them.

After all, though many men may have volunteered out of patriotic devotion, fighting in a war was work: marching and drilling, moving war matériel, building earthworks and bridges, digging latrines, and burying the dead. Only a fraction of a man’s time in the army involved shooting or being shot at; though the risk of sudden and violent death was ever present, he was far more likely to die from disease than from an enemy’s bullet.

In this essay, we examine images depicting the experience of everyday life of the soldiers and the civilians who labored for the army during the U.S. Civil War.

Conrad Wise Chapman, The Fifty-Ninth Virginia Infantry—Wise’s Brigade, c. 1867, oil on canvas, 20-1/8 x 33-7/8 inches (Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth)

Everyday life in the army

Military service was a new experience for the vast majority of men who enlisted to fight in the Civil War. American culture idealized the “citizen-soldier” model of military service—ordinary men who temporarily went to war to defend their country and then returned to their peacetime occupations when the danger had passed. The U.S. government employed few professional soldiers, relying on militias or volunteers to fill the army’s ranks in times of need. Consequently, most of the men who volunteered—for both the U.S. Army and the Confederate Army—had never served in any military capacity before war broke out in 1861. States responded to federal requests for soldiers with hurriedly assembled companies of men, many of whom provided their own weapons, horses, and uniforms. Early in the war, there was a dizzying array of colors and styles on the battlefield as militias and volunteer companies arrived to fight in uniforms of their own design. A town might organize a company that included fathers, brothers, cousins, and childhood friends who marched off to war together; while this increased loyalty and civic pride, it also meant that the better part of a community’s able-bodied men might be killed or injured in a single bad day on the battlefield. This intensely local aspect of Civil War military service helps to explain the monuments and memorials dedicated to a town’s soldiers that proliferated across both the North and the South after the war.

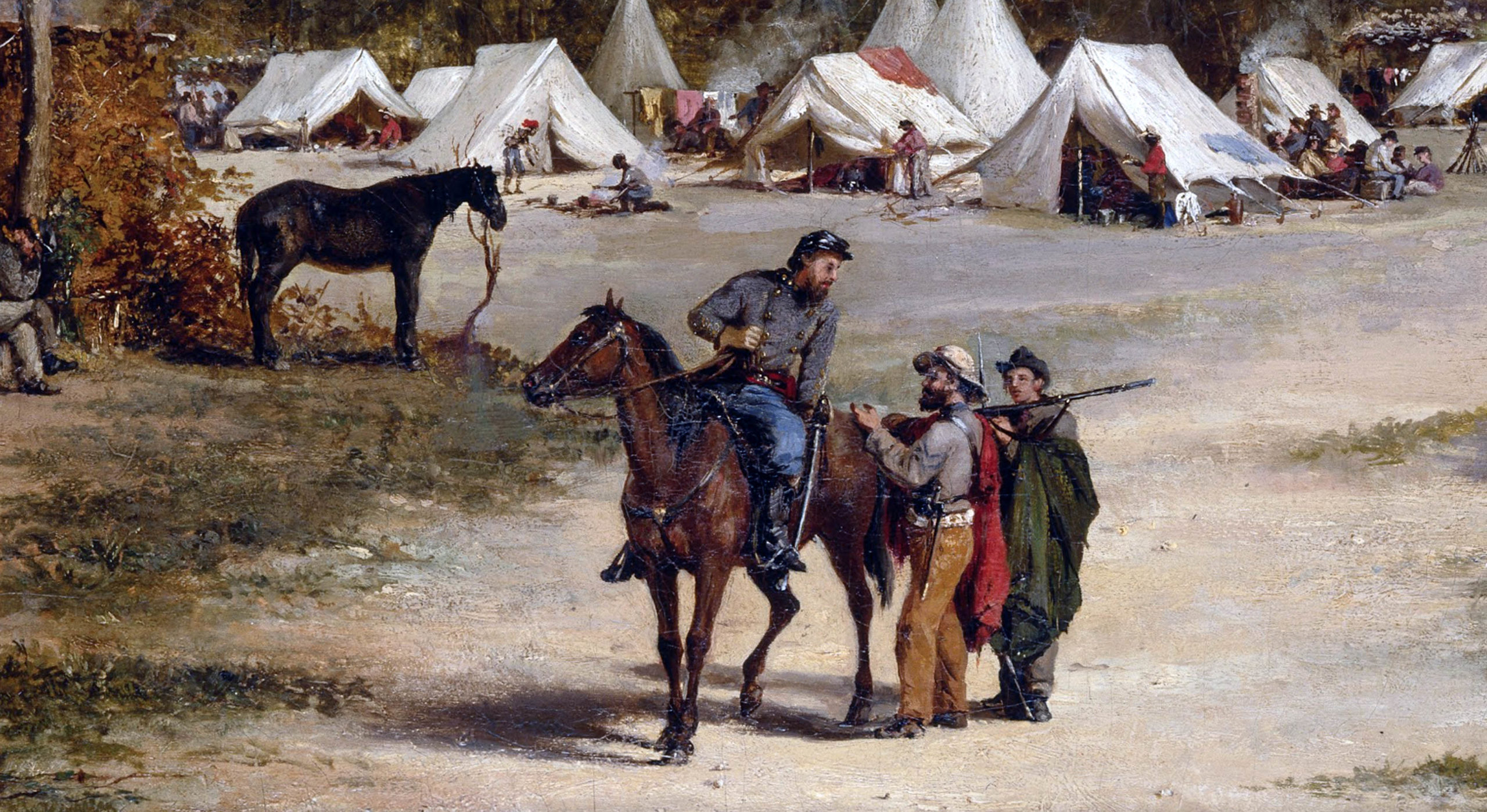

Conrad Wise Chapman, The Fifty-Ninth Virginia Infantry—Wise’s Brigade (detail), c. 1867, oil on canvas, 20-1/8 x 33-7/8 inches (Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth)

Although men enlisted to fight, they spent the vast majority of their time in camp waiting for orders. For every year a man spent in the army he might spend less than two weeks actually engaged in battle. [1] Camp life started as an exciting novelty: pitching tents, learning maneuvers, standing on picket duty (positioned on a defensive line to provide timely warning against an enemy advance), meeting new people, enjoying entertainment, and receiving letters and care packages from home. Conrad Wise Chapman, an artist and Confederate soldier, depicted his experience in camp (using sketches he made on-site) in the painting, The Fifty-Ninth Virginia Infantry—Wise’s Brigade. Mismatched tents and wooden shanties hold up laundry as men chat, play cards, drill, and rest. Trees at left and water and a bridge at right frame the camp and its figures. Chapman uses alternating light and shadow to lead our eye back into space, transforming informal experiences into a formal work of art.

Conrad Wise Chapman, The Fifty-Ninth Virginia Infantry—Wise’s Brigade (detail with Colonel William B. Tabb), c. 1867, oil on canvas, 20-1/8 x 33-7/8 inches (Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth)

Art historian Eleanor Harvey notes that the mounted officer depicted in the center foreground is regiment commander Colonel William B. Tabb, and one of the men conversing with him resembles the artist himself. [2] Closer inspection reveals that there are at least two Black figures in the scene: the man tending the fire just above and to the left of Tabb’s head, and the driver of the wagon near the bridge at right. Both of these men were likely enslaved, brought to the Confederate camp by the white officers who enslaved them. That they are both working in menial tasks—cooking and driving—while the white men find time for leisure activities underscores the white South’s reliance on enslaved labor, even in the midst of war.

Work and family life in camp

The U.S. Army also depended greatly on Black noncombatant military laborers, both men and women, who often performed the most difficult tasks associated with keeping the army running. Early in the conflict, the U.S. government barred Black military labor as well as enlistment, but nonetheless, self-emancipated men and women arrived at army camps looking for work and protection. Although the U.S. government initially instructed military leadership to return these refugees to their enslavers, U.S. Army officers frequently put them to work instead: as personal servants, stevedores, teamsters, and builders. Self-emancipated people deliberately transferred the benefits of their labor, knowledge, and skills from the Confederacy’s enslavers to the U.S. Army, understanding the war’s potential to transform southern society before the U.S. government did. In 1862, Congress authorized federal forces to employ Black laborers, and historians believe that, by the end of the war, a substantial portion of the noncombatant military laborers were self-emancipated people. [3]

Washerwoman for the Union army in Richmond, Virginia, c. 1862–65, hand-colored ambrotype, 9.5 cm x 8.2 cm x 1.6 cm (National Museum of American History)

This rare photograph, believed to depict a Black washerwoman who was with the U.S. Army in Richmond, hints at the investment self-emancipated people felt toward U.S. victory: gazing straight into the camera, the woman wears an American flag on her dress, next to a brass “U.S.” pin. Although her clothing does not appear to be costly, she is posed and attired in a way that would be considered respectable for a 19th-century white woman: hair drawn back from her face, she leans on a draped table, wearing a brooch at her throat. She is self-possessed and resolved, claiming her place as a free woman and an American. [4]

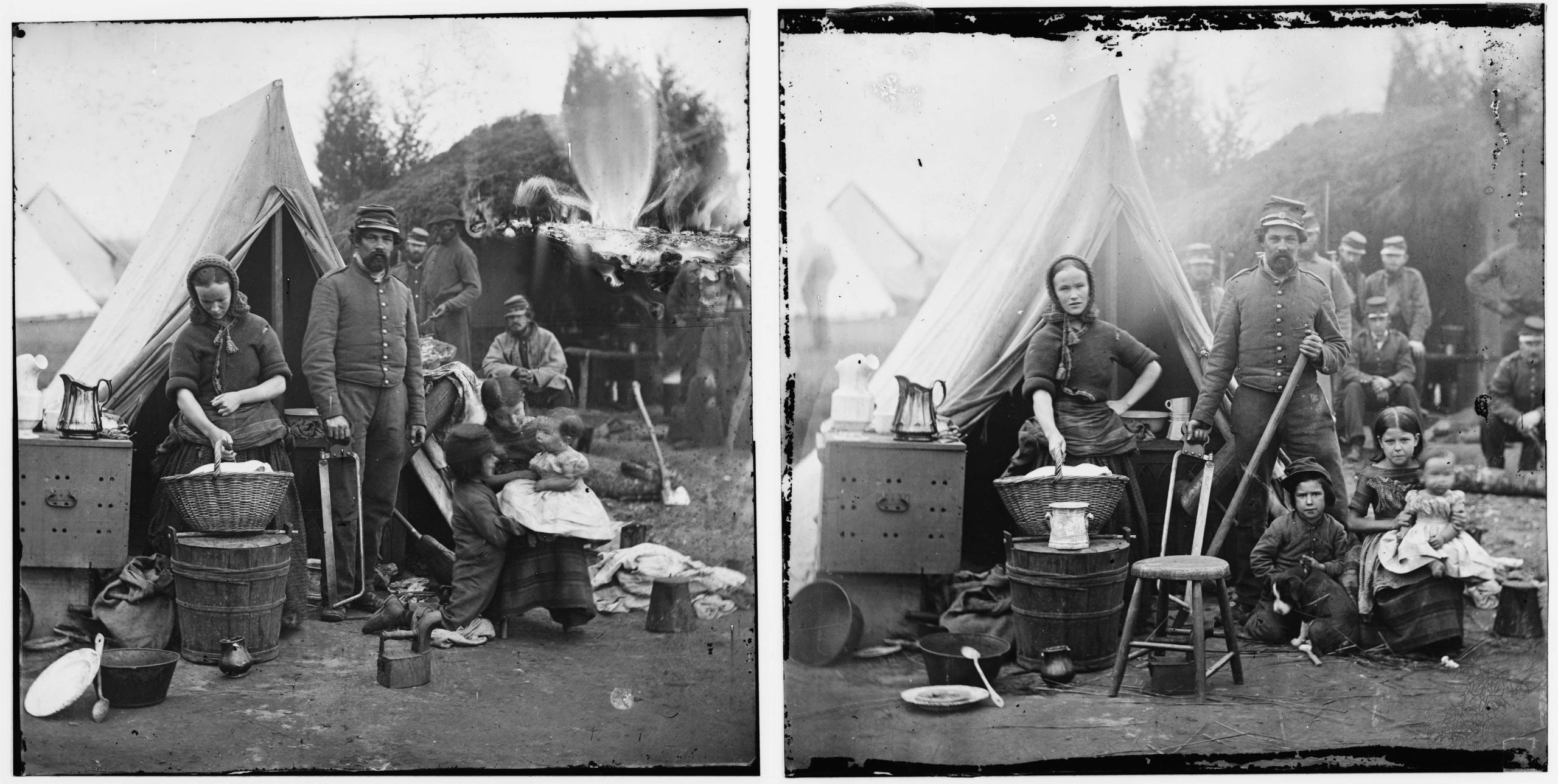

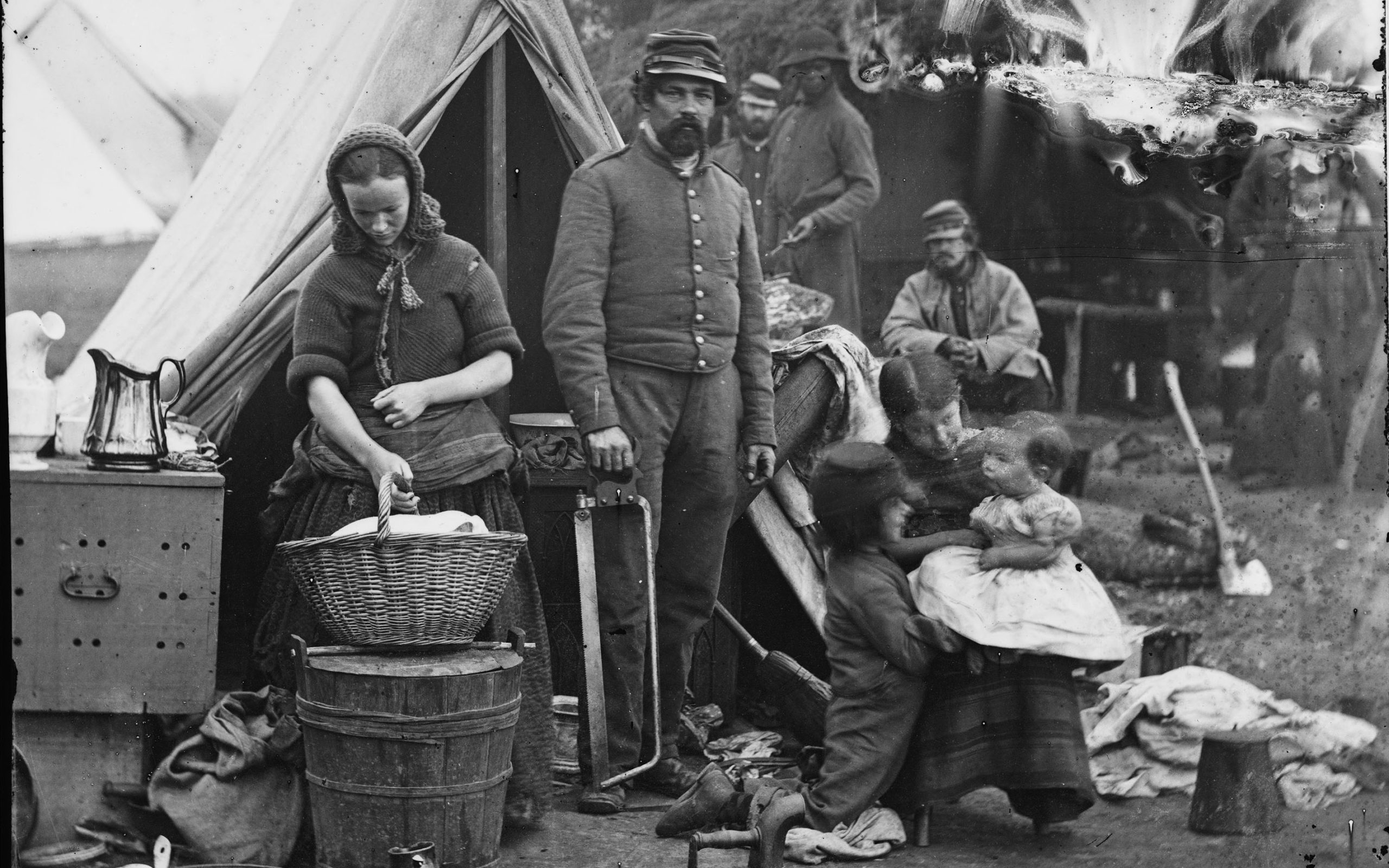

Tent life of the 31st Penn. Inf. (later, 82d Penn. Inf.) at Queen’s farm, vicinity of Fort Slocum, Washington, District of Columbia, 1861, two wet-collodion glass negatives (Library of Congress)

Civil War camps included more women and children than we might imagine today; in some cases entire families—who otherwise might have been destitute—followed their male breadwinner to camp, as in these two 1861 photographs of a Pennsylvania regiment camped outside of Washington, D.C., taken just moments apart. These images tell us a great deal not just about life in camp but also about the nature of photography in the era, allowing us to see more clearly how the photographer composed an image. The cumbersome nature of wet-plate photography, with its large camera, glass plates, and slow exposure time (between 10 and 30 seconds, a long time for a child to sit perfectly still) meant that these images could not be spontaneous. In the image on the right above, which has circulated widely as a depiction of families in camp, the figures look toward the camera with their possessions arranged around them. Two white adults at center hold objects depicting their labors: the woman holds a washtub and basket of laundry, and the man holds a saw and a long-handled wooden implement. Next to them, a little girl balances a baby on her knee, while a little boy, wearing a kepi, holds tight to the collar of his puppy. In the background, there are seven more men looking at the camera, some seated and some standing.

Tent life of the 31st Penn. Inf. (later, 82d Penn. Inf.) at Queen’s farm, vicinity of Fort Slocum, Washington, District of Columbia (detail), 1861, wet collodion glass negative (Library of Congress)

The other photograph, likely taken first, allows us to see how the more famous image was carefully composed through positioning people and objects. There are fewer household goods visible in this version, and fewer figures in the background. The puppy has not yet arrived. Most notably, there is a Black man (wearing a long coat and a round-brimmed hat) near the center of the composition. In the first photograph he is barely recognizable at the far right, half cut out of the image. These images help us see how photographs can both reveal and obscure their subjects, showing us a more complex picture of camp life than we may have imagined and yet one that is not as neutral as it initially appears.

When Congress authorized Black enlistment a year after these photographs were taken, much of the military labor for the U.S. Army would be taken on by Black enlisted men, who often were assigned to labor detail rather than combat. Black men frequently served as teamsters, driving the wagons and caring for the pack animals that furnished the northern supply line. As the U.S. Army was on enemy territory, invading the South to reestablish control, supply lines were critical to keep the soldiers provisioned; historian James McPherson estimates that a campaigning army of 100,000 required 2,500 supply wagons, 35,000 animals, and consumed 600 tons of supplies every day. [5]

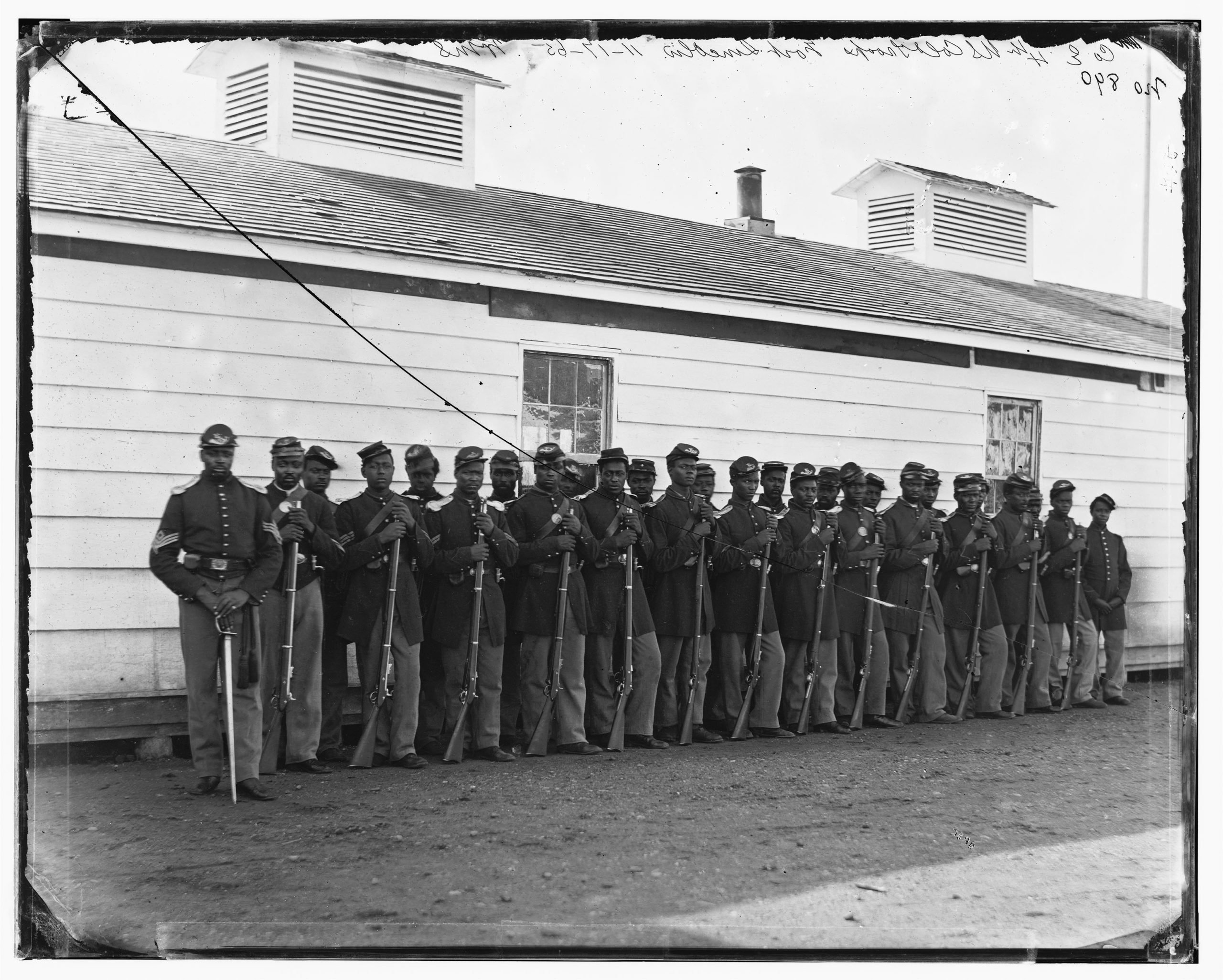

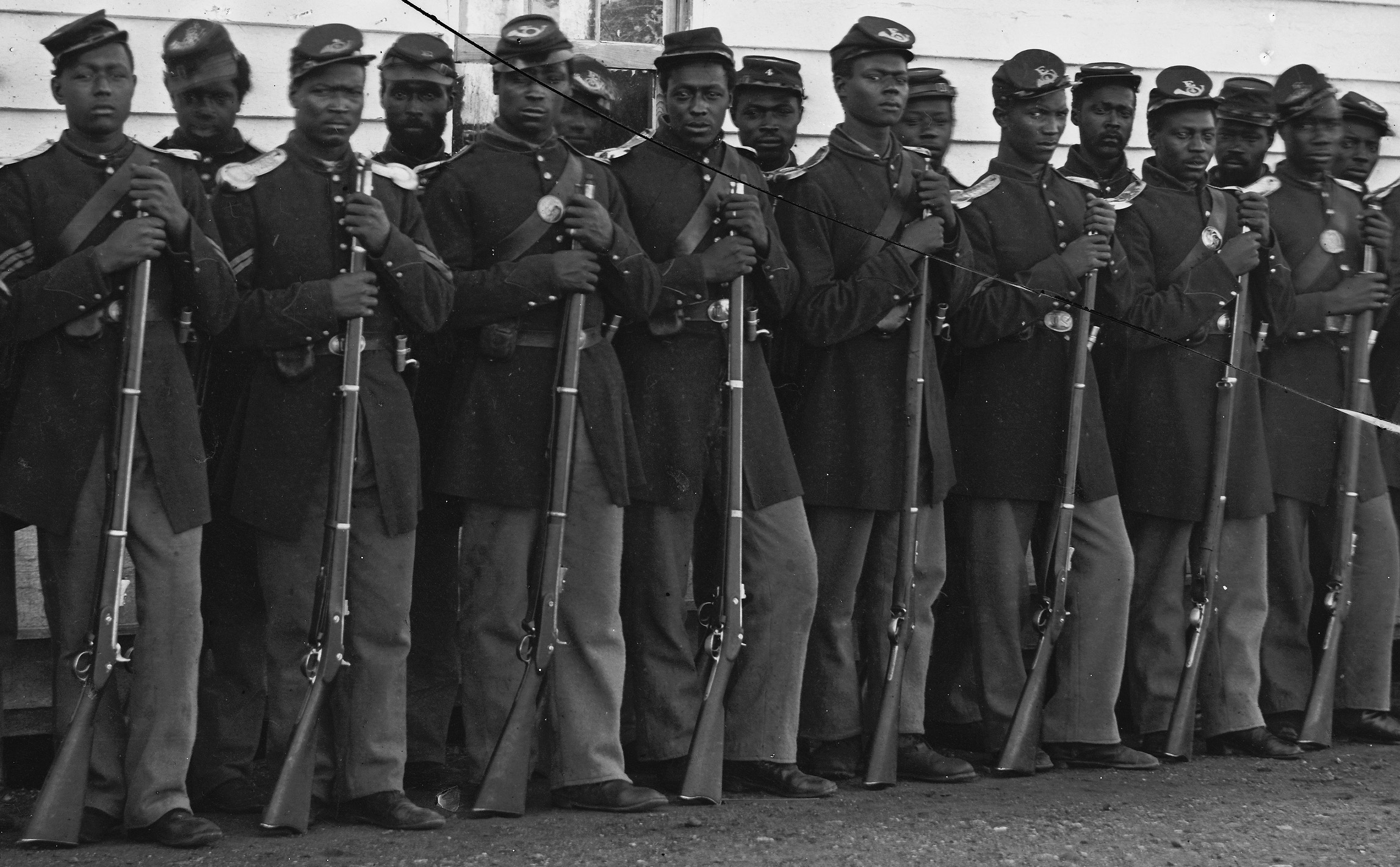

William Morris Smith, Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln, District of Columbia, 1863–66, wet collodion glass negative (Library of Congress)

Valorous military service was a powerful claim to manliness and citizenship, and Black men (both those who were born enslaved and those born free) were eager to wield rifles, not just shovels. The U.S. government’s decision to enlist them in 1863 provided its army with much-needed manpower at a time of falling northern enlistment, and it linked the U.S. war effort inextricably with abolition in the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation. Early fears among white detractors that Black men would not make capable soldiers were put to rest by Black regiments’ achievements at battles at Port Hudson and Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana, and at Fort Wagner, South Carolina.

William Morris Smith, Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, at Fort Lincoln, District of Columbia (detail), 1863–66, wet collodion glass negative (Library of Congress)

Approximately 179,000 Black men served in the U.S. Army and another 18,000 served in the navy over the course of the war. [6] They fought both an external war with the Confederate enemy and an internal one with the U.S. War Department, which resisted their demands for awarding Black soldiers equal pay or permitting Black men to become officers until 1865. Photographs of Black men in U.S. Army uniforms—which signaled their willingness to sacrifice their lives for the nation as well as their intent to submit to the rule of its government—created “the first possibility of imagined national black manhood,” in the words of scholar Maurice O. Wallace. [7] This photograph of Company E of the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, which was assigned to the defense of Washington, D.C., emphasizes the orderliness of Black soldiers. Standing with their rifles upturned in two neat rows outside of a barracks, the men of Company E exemplify the discipline of citizen-soldiers in service to the government.

George Smith Cook, View from a parapet, Charleston Harbor, S.C., 1863, albumen print on card mount (Library of Congress)

Picturing fighting and the battlefield

All of the work to support the army was, of course, undertaken to support its ability to fight. Nevertheless, there are very few photographs of Civil War battles in progress: camera emulsions were not sensitive enough at that point to capture people and objects in motion. One very rare exception is a photograph, taken by a Confederate named George Smith Cook in 1863, showing U.S. ironclad ships firing on a fort in Charleston Harbor. The image is unclear, but the ships in the distance were firing on the fort where the photographer stood. More often, we have photographs of the preparation (earthworks, battlements, men posing in front of tents) and of the aftermath (buildings and bodies in ruins) so we must rely on the human imagination and memory for images of battle itself.

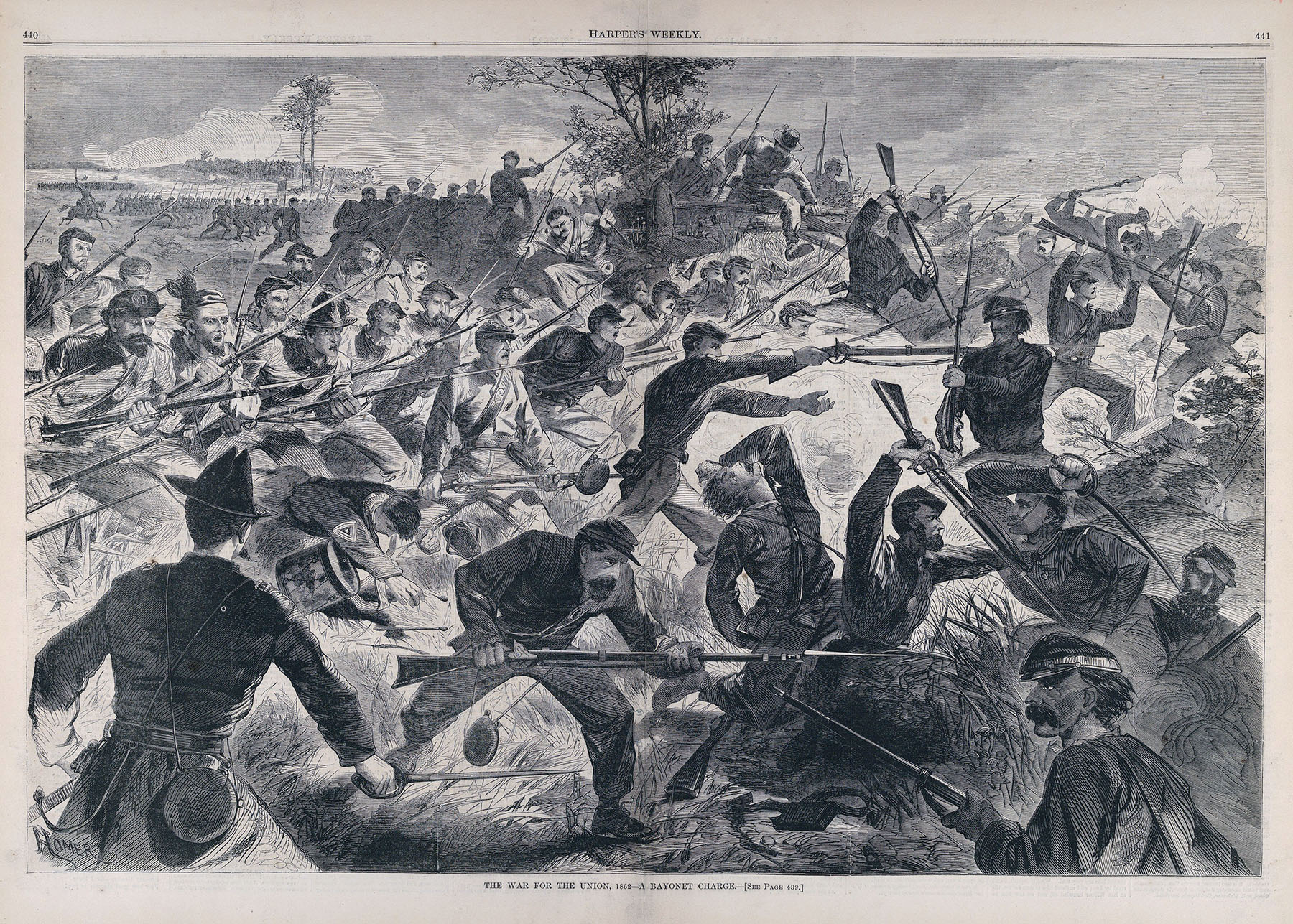

After Winslow Homer, “The War for the Union, 1862—A Bayonet Charge,” Harper’s Weekly, July 12, 1862, wood engraving on paper, 40.8 x 57.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Sketches from special artists like Homer attempted to capture the violent fray, as in his depiction of a bayonet charge during the Battle of Seven Pines in Virginia on May 31, 1862. It is unlikely that Homer was close enough to see this charge firsthand, relying instead on artistic conventions of portraying battle. [8] Nevertheless, Harper’s Weekly described the image as a rare opportunity for civilians to “see” soldiers fighting each other at close range:

[S]oldiers seldom actually cross bayonets with each other in battle. . . . At [Seven Pines] the rebels almost invariably broke and fled before our bayonets reached them. In one or two instances, however, there were hand-to-hand tussles at particular points. One of these is realized in our picture.Harper’s Weekly [9]

In the engraving, men drive from the left meeting their foe in close combat, the terror and anger plain on their faces. The artist has succeeded in conveying the chaos of the battlefield combined with a sense of proximity that makes the viewer feel that they too are in harm’s way. An officer at the bottom left, his sword down, as if he has just given the command to advance, unleashes the assault. Two soldiers appear to be early casualties of the battle: the figure falling to his knees with his bent arm raised in pain and the drummer boy just behind, whose side drum tumbles as he does while his kepi and drumsticks fly forward—perhaps shot by the menacing rifleman at the bottom right. Despite Harper’s claims that the battle (which ended without a clear victor and similar numbers of casualties on both sides) was “realized” in its image, the engraving nonetheless presents a vision of the bayonet charge that its northern audience would approve. As the text claims the Confederate soldiers fled before the U.S. bayonets, so too does the image focus on the heroics of the U.S. Army, with a triangular arrangement of soldiers taking up nearly two thirds of the composition, giving them a sense of triumphant momentum.

The varied work of war

Images show us the lives of soldiers, workers, and their families during the Civil War as they traveled to the battlefield and survived in camp off of it. Though our perception of the soldier’s job may focus on combat, the work of war was much more varied than fighting alone—as were the people who did that work. But even though our attention to the experiences of a diverse and dynamic army can show us a detailed picture of life at war, we must remember that each of these depictions of the work of war was composed for a reason and an audience. After all, art was war work as well.

Notes:

[1] Gary Helm, “Life of the Civil War Soldier in Camp: Disease, Hunger, Death & Boredom,” American Battlefield Trust.

[2] Eleanor Harvey, The Civil War in American Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), p. 132.

[3] Thavolia Glymph, “Noncombatant Military Laborers in the Civil War,” OAH Magazine of History 26, no. 2 (April 2012): pp. 25–29.

[4] Deborah Willis and Barbara Krauthamer, Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012), pp. 71, 118–119.

[5] James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 325.

[6] Ira Berlin, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, Freedom’s Soldiers: The Black Military Experience (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), pp. vii, 11–14.

[7] Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith, eds., Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and the Making of African American Identity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), p. 246.

[8] Lucretia Hoover Giese and Roy Perkinson, “A Newly Discovered Drawing of Sharpshooters by Winslow Homer: Experience, Image, and Memory,” Winterthur Portfolio 45, no. 1 (2011): p. 82.

[9] Harper’s Weekly, July 12, 1862, p. 439.

Additional resources

Learn more about Winslow Homer from the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Educator resources on Black soldiers in the Civil War from the National Archives

Deborah Willis, The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict and Citizenship (New York: New York University Press, 2021).

Thavolia Glymph, The Women’s Fight: The Civil War’s Battles for Home, Freedom, and Nation (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020).