Majority to minority and back again

Essay by Dr. Bryan Zygmont

Power in the United States—and, some might say, most countries—is a matter of politics. Sometimes these politics are rooted in grassroots efforts, and sometimes they are propelled by the power of mass media. Throughout the history of the United States, politics and power have been intertwined and inseparable.

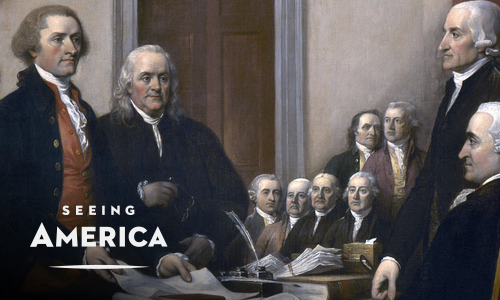

Alexander Hamilton and the two-party system

Few understood this better than Alexander Hamilton, the First Secretary of the Treasury and personal and political confidant to General (and later President) George Washington. Interestingly, although Hamilton was the de facto leader of the Federalist Party—a group unified in part by their Anglophile tendencies—he was never elected to significant political office (although he did serve during the third and tenth Congress of the Confederation during 1782–83 and 1788–89). Yet despite this lack of elected office, Hamilton holds a crucial position in the development of the two-party system in American political history.

As the Federal Period moved onward, the two-party system in the United States developed into the Federalist Party and the Democratic Republican Party. At first, the Federalists led the government under the presidencies of George Washington and John Adams, and they aspired to link the American economic and diplomatic future with Great Britain. Afterwards, with the election of the Francophile Thomas Jefferson in 1801, the Democratic Republicans took control. Generally, Democratic Republicans believed that the revolutionary zeal in France most accurately matched their own. This shift in political leadership during the early nineteenth century from the Federalists to the Democratic Republicans illustrates one of the fundamental elements of a two-party democracy: that is, there is generally a majority and a minority party, and the minority party can become the majority party.

Face-to-face with voters

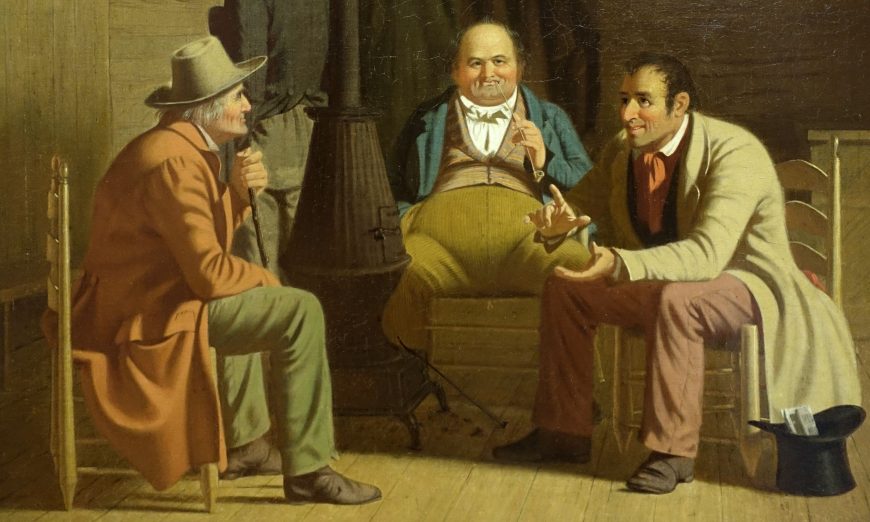

George Caleb Bingham, Country Politician (detail), 1849, oil on canvas, 51.8 x 61cm (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco)

This swapping of political power necessarily involves how political candidates communicate with those who elect them. With this in mind, it is not surprising that artists turned to this subject as a way of commenting on the political process. George Caleb Bingham was one such painter. Although born in Virginia, Bingham’s family moved to Missouri in 1819, two years before it was admitted as a state. The artist later spent time on the east coast—studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia and painting portraits in Washington, D.C.—but we most identify his career today with the Midwest. It was in Missouri where Bingham would later forge successful careers as a painter and as a politician.

Bingham painted Country Politician in 1849, a period in his life when he was serving as a Whig—a kind of neo-Federalist—in the Missouri state legislature. Although at first glance it seems to be a simple composition—three figures are seated around a wood-burning stove while a fourth figure stands in the background looking at a poster and newspaper clippings pasted to the wall—it is, in fact, a complex work of art that eloquently speaks to political process, and to an important debate of the time.

The Wilmot Proviso

The three figures who sit around the stove fit certain types. The affluently dressed man in the middle holds a lit pipe and looks toward the viewer while listening to the gesturing man on the right who is clearly speaking with the elderly man on the left. Given that Bingham painted this scene in Missouri in 1849, it would be unsurprising if the topic the politician discusses were that of the Wilmot Proviso, a contentious bit of legislation intended to ban slavery in states that joined the Union during (and following the conclusion of) the Mexican-American War (1846–48). In the years preceding the Civil War, this act was of paramount importance, for it could have shifted the political balance in the American congress between the so-called Free and Slave States. The Wilmot Proviso twice passed the House of Representatives before failing in the Senate where the southern states had a greater proportion of votes with which to defeat the bill.

If the man speaking is the country politician of the painting’s title, he makes his case for his candidacy. We in the twenty-first century are accustomed to receiving political messages through Twitter or the myriad of cable news networks. In the mid-nineteenth century, however, our country politician uses his own method of communication: speaking face-to-face with the (male) voters who might support him.

Politics through the media

Gary Winogrand, Democratic National Convention, Los Angeles, 1960 (printed c. 1980), gelatin silver print, 45.88 x 30.8 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art, © The Estate of Gary Winogrand).

But as time moved onwards from the nineteenth century, the method of communicating with the electorate clearly changed. This is obvious when looking at Garry Winogrand’s photograph, Democratic National Convention, Los Angeles, 1960. In it, the recently nominated John Fitzgerald Kennedy stands with his back to the viewer, while the bright lights that illuminate his visage for the television cameras create a kind of heavenly halo around his head.

The lineup of partially concealed television cameras situated on tripods in the upper background record his likeness, while the microphones in front of him at the podium record his Bostonian accent. Clearly, candidate Kennedy is not only speaking to the thousands standing at the Biltmore Hotel on 15 July 1960. He is also speaking to the millions of Americans who are seeing his nomination acceptance speech broadcast on network television while seated on the sofas in their living rooms across the nation, an idea reinforced by the television screen—with Kennedy’s face upon it—in the lower part of the photograph.

A variety of opinions

But it is not only politicians who express political views. This is, of course, a right that is protected for everyone in the United States under the First Amendment, and sometimes, those political views make their way into objects that could be considered utilitarian and quotidian objects. The Snake Jug is one such object. Cornwall and Wallace Kirkpatrick created this whiskey jug in 1865 in the small town of Anna, Illinois (a hamlet in the southern tip of the state), and although its decoration to modern eyes may appear enigmatic, an immediately-post-Civil War viewer would have had little difficulty in identifying the political message contained on the vessel.

Anna Pottery, Snake Jug, c. 1865, stoneware with painted decoration, 31.75 x 21.11 x 22.07 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

The most recognizable elements that appear on this earthenware jug are the snakes that encircle its periphery and pierce its center. But these are not just any, garden-variety snakes; their darkened heads identify them as copperheads, snakes that became the symbol of the “Copperheads” (sometimes called the Peace Democrats, so named because they called for a peaceful conclusion to the Civil War). Generally speaking, the Democratic Party during the Civil War was focused in the American South, whereas the Republican Party was strongly anti-slavery and found in the northern part of the country (Abraham Lincoln, for example, was a Republican from Illinois). Thus, although the Copperheads were from Northern states (which were generally pro-Union and anti-slavery), this Party was much more akin to their Confederate brethren in the South with regard to their political and economic leanings.

And this oddity—that pro-slavery sentiments could be found in the North—is an important one. Just as there are a panoply of political views in the United States, so too are there a variety of opinions on any one political (or economic or social) issue in any one given state. Although we currently refer to Red States and Blue States, we are only commenting on a majority leaning and not on a unified view. Part of our democracy dictates that our political views can be expressed regardless of whether or not they are the predominant view on our own street (or neighborhood, city, state, or country). Communities may have leanings or tendencies, but in our democracy, the minority view retains the opportunity to express itself with the hopes of becoming the majority.

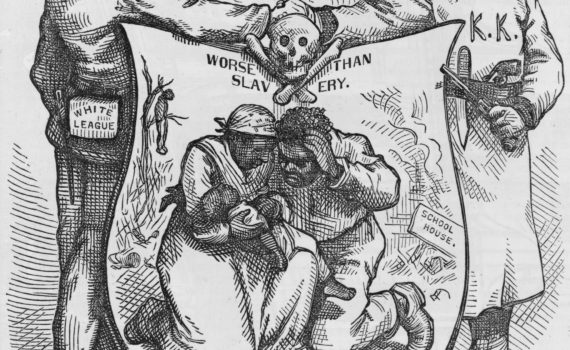

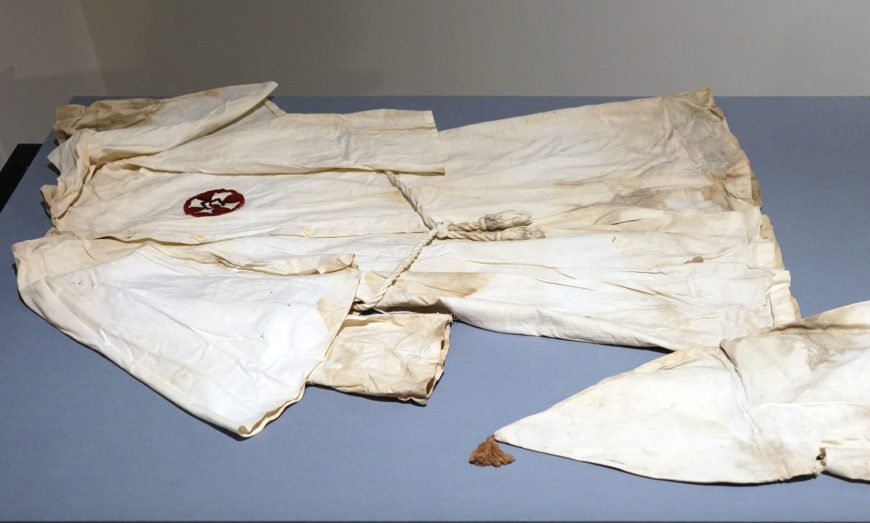

A Ku Klux Klan robe — from Connecticut

Ku Klux Klan robe, c. 1928 (The Amistad Center for Art & Culture at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford)

Nowhere is this more clear than it is in the Ku Klux Klan robe on display in the Amistad Center for Art and Culture at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut. The KKK has gone through several reinventions since it was first founded in Pulaski, Tennessee in the years following the Civil War. The primary goal of the organization was to—through terror and threat of violence—eliminate the rights granted to recently freed slaves through the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution. But five years later, the Civil Rights Act of 1871—sometimes called the Ku Klux Klan Act, effectively ended this first era of Klan history.

The Klan resurfaced in 1915 in Stone Mountain, Georgia. The second era of Klan history was largely inspired by the release of D.W. Griffith’s film Birth of a Nation, a movie that premiered earlier that same year. This second iteration of the Klan had similar goals to the first: to terrorize all those who they thought were non-white (this included, of course, African Americans, but the KKK also considered Catholics, Jews, and those of southern and eastern European descent non-white, too). The garments in the Amistad Center are important for many reasons, but especially because of when they were made and where they were used. There is a myth that suggests that the KKK was a uniquely southern phenomenon, and so too was slavery. But these robes testify to the fact that such sentiments could also be found in the North—in this instance, in Connecticut—during the second quarter of the twentieth century. Although the state of Connecticut was on the Union side during the Civil War, slavery had been legal in Connecticut prior to 1784, and these garments eloquently remind us of the conflicts that underlie these facts.

Few would consider these garments works of art. Someone clearly designed the robes, but they were inexpensive, mass produced, and the major goal, it seems, was to hide the wearer’s face so he could behave in a way contrary to societal norms. Moreover, most viewers do not look for an aesthetic experience in this garment, but are instead filled with a level of disgust because of the hatred that they represent.

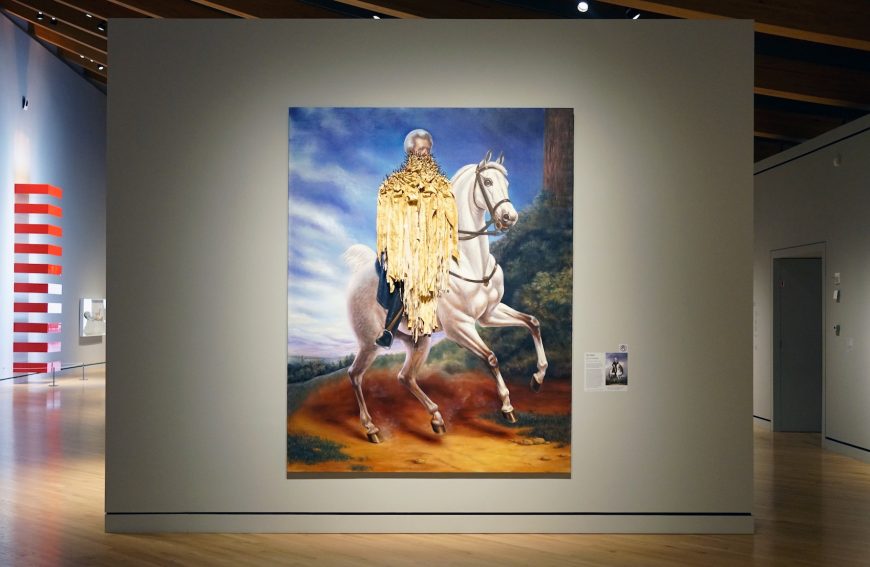

Titus Kaphar, The Cost of Removal, 2017, oil, canvas, and rusted nails on canvas, 274.3 × 213.4 × 3.8 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

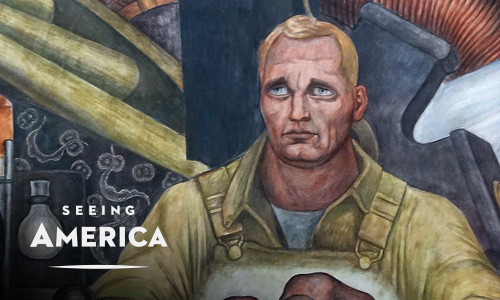

Heartbreaking legacies

The meaning of certain objects may suggest one thing to a viewer around the time of its creation, and whisper another message to the generations that follow later. Artists often aspire to comment on this. Titus Kaphar created the larger-than-life-sized The Cost of Removal in 2017, and the object is, at some level, about the shifting view of the seventh president of the United States, Andrew Jackson. In this twenty-first century work, Kaphar has recreated an approximation of an equestrian portrait of the Hero of New Orleans that Ralph Earl painted in 1833.

Rather than emphasize the politician’s dignity (as portraits often try to do), Kaphar has instead obscured the sitter’s body and head through the use of torn strips of canvas with Jackson’s own writing upon it that are secured to the president’s head with nails. In doing this, the artist comments on one of Jackson’s most enduring legacies: the removal of Native Americans from their southeastern lands by force, following the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The so-called Trail of Tears that followed—the paths of those native peoples to the Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma—resulted in thousands of deaths and generations of continuing heartbreak.

President Donald J. Trump participates in a Christmas Day video teleconference from the Oval Office Tuesday, Dec. 25, 2018, with military service members stationed at remote sites worldwide to thank them for their service to our nation. (Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead)

When Donald Trump began his tenure as the 45th president, he had a Thomas Sully portrait of Andrew Jackson hung in the Oval Office of the White House, an image that might speak different political messages to different political groups. For many, Jackson’s likeness suggests his populist roots, something Trump’s presidential candidacy shared and embraced. For others, Jackson was an unabashed racist who attempted to systemically displace entire groups of people. What we think of Jackson, and what we remember of his military career and his presidency, has shifted over time.

For example, in 1928, Jackson was removed from the $10 bill and “promoted” to the $20 bill (in honor, presumably, of the 100-year anniversary of his presidential election), and the face on the $10 bill was replaced with that of Alexander Hamilton. In June 2015, the Secretary of the Treasury announced that Hamilton’s likeness on the $10 note would be replaced with that of a yet-to-be determined woman. But in the months that followed, the American public rediscovered Hamilton through Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical. And so, in April 2016, it was announced that Hamilton’s head was safe on American currency, and Jackson’s likeness on the $20 bill was to superseded by that of Harriet Tubman, the great conductor of the Underground Railroad who ushered escape slaves northward to freedom.