There are many kinds of Buddhist meditations; here Dr Sarah Shaw describes the ‘middle way’ of the Buddha and explores key aspects of Buddhist meditation and chant, such as the use of Buddha-images and visualisation.

Some key acts of Buddhist practice are meditation and chanting. They are a continuation of the teachings of the Buddha, in that they are both felt to bring peace and fulfilment, and help us to lead happier lives. You might have seen a Buddha image, and noticed the sense of reassurance and stability it offers. These are the qualities meditation can arouse in us. Chant is considered helpful by some to strengthen these qualities too. So what do we know about the Buddha, and the path he taught for others to follow?

What did the Buddha teach about meditation?

The Buddhist eightfold path of practice is a way of living and training the mind, taught by Gotama Buddha in the 5th century BCE. Born to a wealthy family, he wanted to find a way to freedom. Leaving his palace, he practised some austere meditations and, sometimes, self-mortifications. But they did not bring peace or wisdom. One day, however, he remembered a simple meditation called jhāna he had found for himself when left alone as a young man under a rose-apple tree. Jhāna is a completely joyful and peaceful state of unification. He asked himself if this might be the way to freedom. Under a Bodhi tree, he practised this and other meditations, and found ‘the middle way’: a path to free the mind from circles of unhappiness and suffering. Meditation remains a central part of this.

The path he taught after his awakening reflects the sense of balance of the middle way. The first two factors influence how we think and understand events: right view and right intention. Some concern how we behave to ourselves and others: right speech, right action and right livelihood. The last three concern meditation, and the practice the Buddha had found for himself: right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration. The middle way, and balance, can be found in all of these areas of life.

What are samatha and vipassanā?

Two qualities, calm and insight, are said to be needed to be in balance for the Buddhist path. Some meditations stress the insight aspect of their path; seeing unsatisfactoriness, impermanence, and the absence of an abiding self in events that arise in life and in the mind. This is called insight (vipassanā), and links to the first two path factors. Other types of meditation put more emphasis on calm and finding stillness, happiness and unification first – often needed for Westerners. Samatha means calm, and refers to jhāna practice. It emphasises peace and deeper stages of meditation, leading to a serene equanimity and balance. This is linked to the last three path factors.

We need calm and insight for most things in life. We need some happiness and tranquillity in things we do, or else we simply do not enjoy them, and feel unhappy and pressurised. Many young people and Westerners feel then the need for a practice that helps bring calm and peacefulness. But we also need to have a sense of the ‘three signs’: that nothing can be perfect, that things change, and that we change too. In fact this is good news: if a piece of work is not exactly as one wanted it to be – it is unsatisfactory. If one gets up in a bad mood it is helpful to reflect that that is not necessarily an abiding self, but one we happened to find in the morning, and do not have to keep!

How do Buddhists meditate?

Buddhist meditation generally takes a simple object, often the breath, and offer techniques to practise mindfulness and arouse awareness with it. This brings peace and ease with the way the breath rises and falls. If we feel some stillness and happiness in the breath, we can feel peaceful and unified during the day too. The breath arouses calm, as it becomes very unifying and pleasant to be aware of it; the meditator can then develop jhāna. The breath also arouses insight, as the mind feels at ease in its constant ebb and flow, and sees impermanence in the breath’s movement in and out of the body. When both calm and insight are present, the meditation is in balance. The texts describe many such meditations, of different varieties. Loving kindness (mettā-bhāvanā), for instance, is a popular calm practice linked to mindfulness that helps you to feel comfortable with yourself, and others around. In this meditation you wish for your own happiness, and all other beings too. If you are kind to yourself, you are more likely to find it easier to feel kindness for others.

These meditations work with the three ethical factors of speech, action and livelihood. They are said to protect the mind in daily life, and are important as a basis for all meditation.

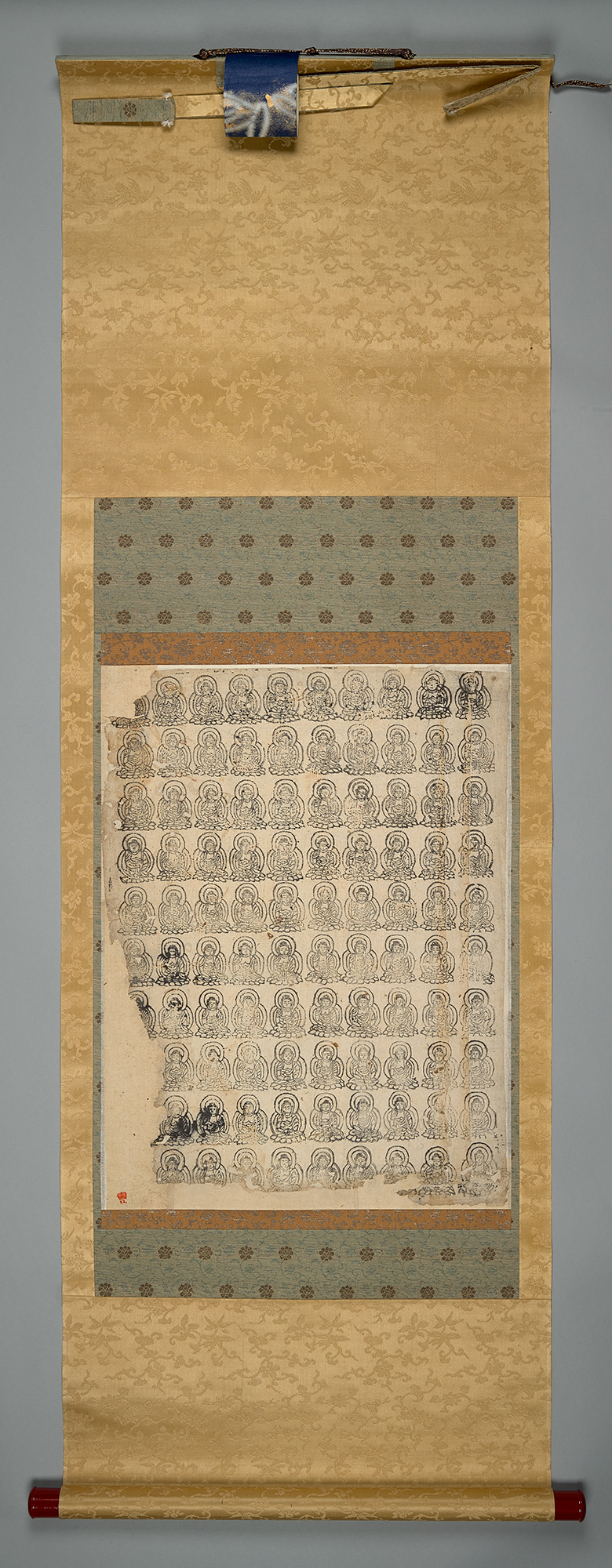

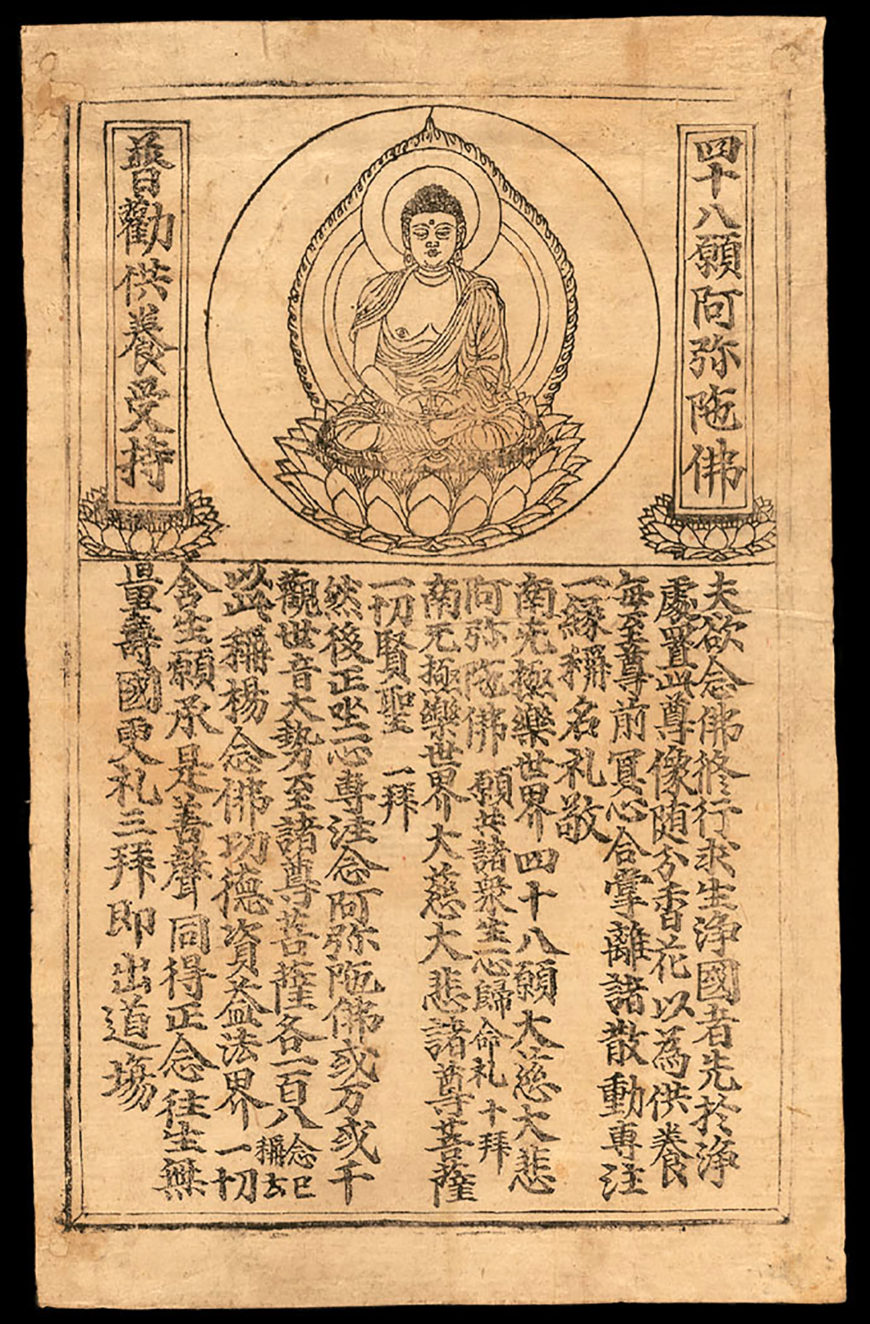

This votive prayer sheet, which was found sealed inside an Amitābha Buddha statue at Jōryuji temple in Japan, depicts one hundred images of Amitābha Buddha printed on paper. Votive objects were frequently sealed in Buddha statues in all Buddhist traditions. One hundred seated images of Amida Nyorai, early 12th century, Japan (The British Library)

What are Buddha images?

Buddha images and pictures are also significant for meditation, for they are visual teachings. Anyone can look at a Buddha and appreciate the peaceful alertness, tranquillity, and sometimes, a smile. Traditionally in non-literate societies they were very important. People would see a Buddha and the smoothly rounded shoulders, the straight but relaxed back, the sense of balance and steadiness would communicate this. Over hundreds of years after the Buddha died, Buddhism travelled from India to Southeast Asia, Indonesia, China, Korea, Japan and Tibet. It is not surprising that Buddha images and pictures start to look like the people that lived in those regions, and they are adorned and depicted in ways that would be natural to that region too. They are often surrounded in pictures by local gods and deities, natural to the area and the culture of the people there. After a hard day at work, people could visit a temple, and could easily ‘read’ a Buddha image, pictures about the Buddha’s life and past lives, and feel their own mind and body restored by them.

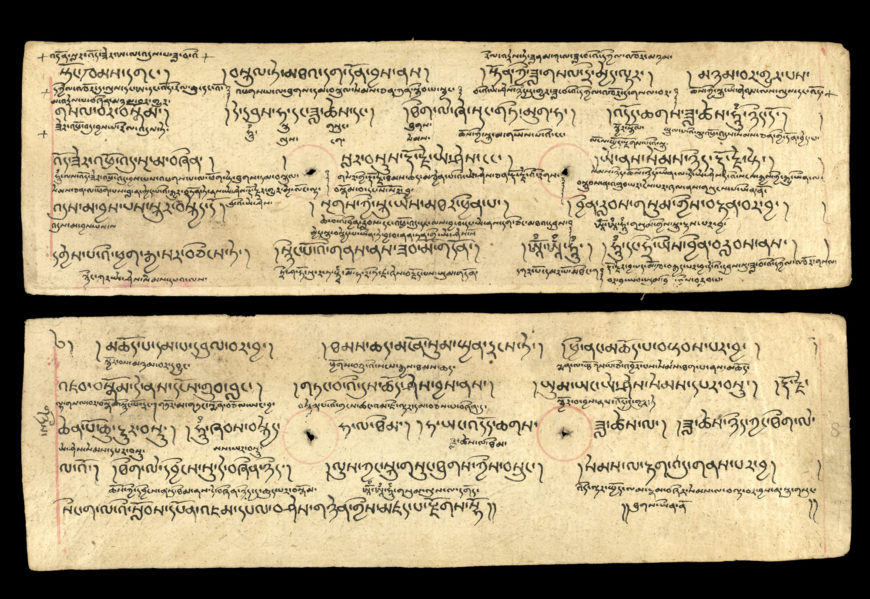

A Tibetan manuscript provides instructions for tantric meditation practice. These practices include visualisation of Buddhist deities and their maṇḍalas, chanting mantras, and forming hand gestures known as mudrā. Three Tibetan Mahāyoga sādhanās, 900–1000 C.E. (The British Library)

What is Buddhist chanting?

Such images were and are used as objects of devotion. The person sitting or kneeling in front of them makes offerings of flowers, lights and incense, and meditates or chants. This is a way of paying homage, honouring, and hoping that the qualities in the image might arise in them too. The Buddha represents the human mind at its full potential, with great understanding, calm and a profound wisdom. Buddhism suggests that this awakened wisdom and peace is possible in all human beings too, but needs to be cultivated, or found. Just by sitting in front of the figure, and paying respects to it, Buddhists, or sometimes those just interested in Buddhism, can also feel intuitively a connection with the Buddhist path and the way to freedom. So some meditations are chants, refuges to the Buddha, to his teaching, and to his followers. There are also longer chants, called ‘recollections’ (anusṃrti/anussati), reflections on the possibilities of an awake mind, the teaching that can bring this, and other beings who have followed and teach the path to freedom.

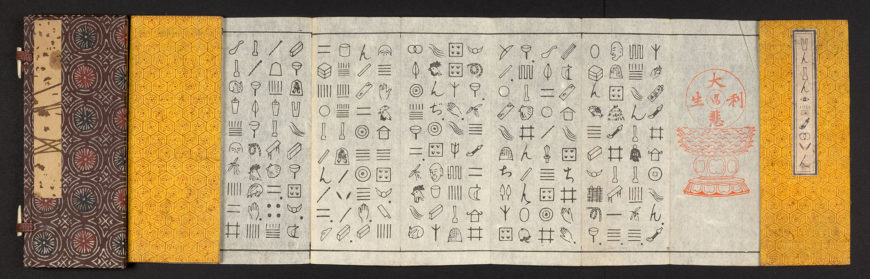

This small, Japanese folding book contains the text of the Heart Sūtra represented in pictures and was intended to allow illiterate people to recite this popular Buddhist sūtra. Sutra for the Illiterate, early 20th century, Japan (The British Library)

The chants introduce meaning and purpose into one’s life, and are often communal. Anyone, anywhere, can sense connectedness with the Buddhist path; chanting settles the mind to enter meditation, or to feel part of a larger group in a temple. Some chants remembering the qualities of the Buddha are used in daily life too, outside the temple. In this way Buddhists can chant a simple recollection of the Buddha, while working, or going about their daily lives. They feel that everything they do is thus changed by this. If the chant becomes natural, they feel they might be reborn in a Pure Land, a heaven realm on the way to liberation. Some practitioners say that such a heaven is the mind itself, when it is free from distractions and problems.

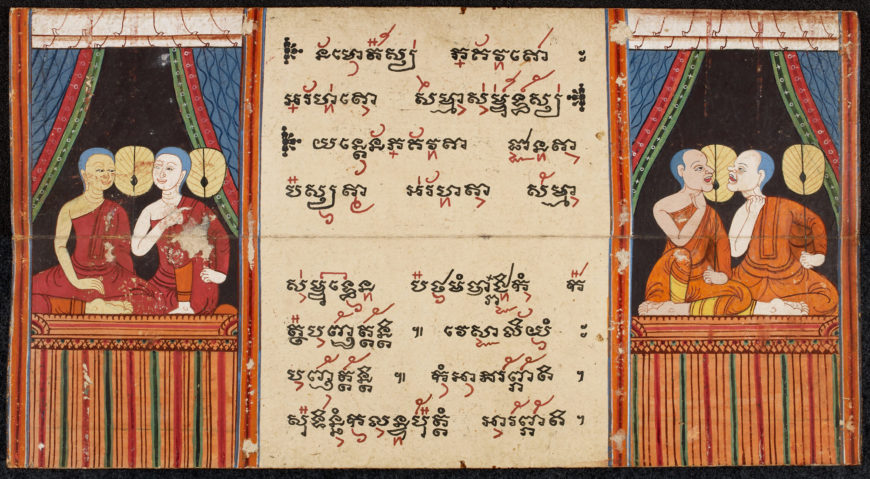

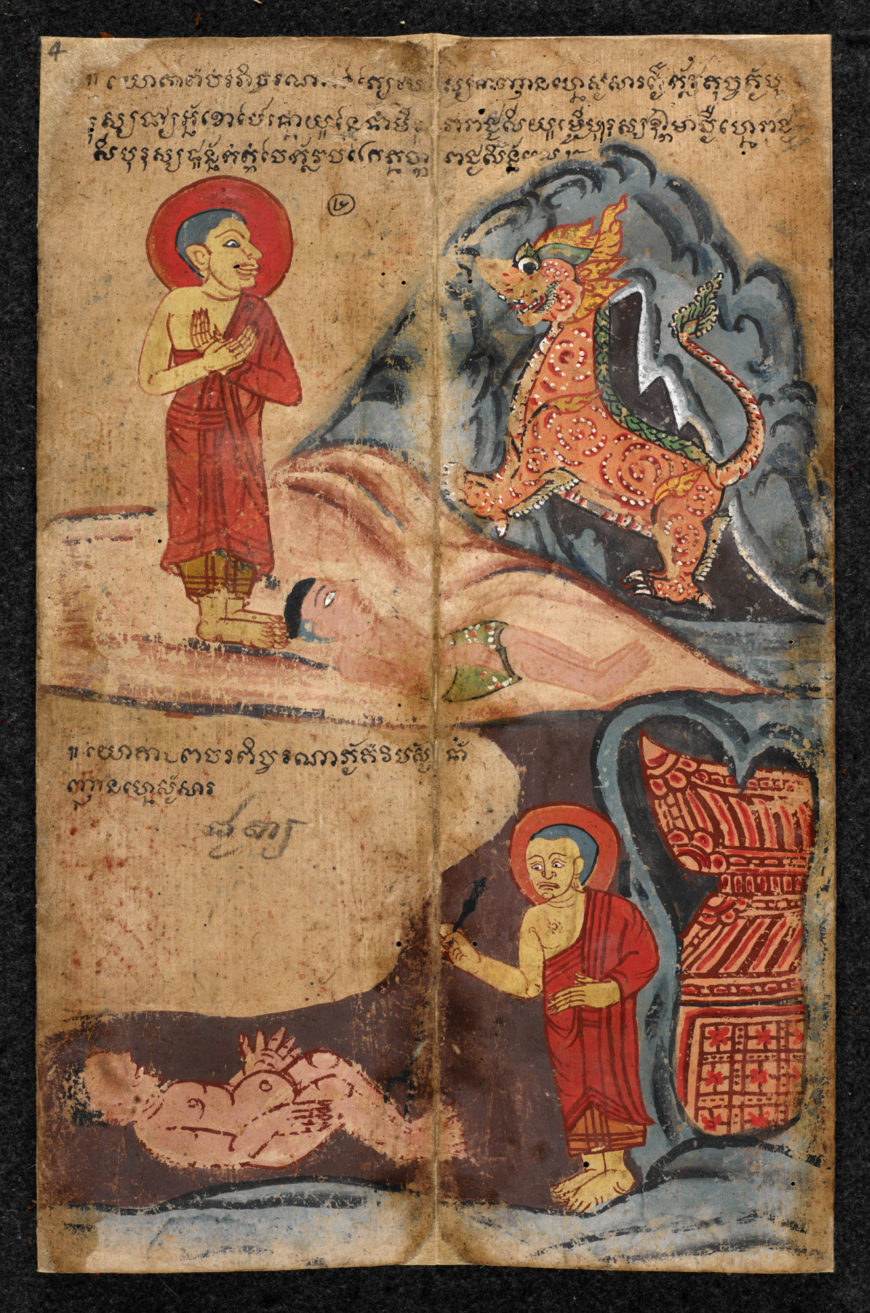

Thai folding book containing extracts from the Abhidhamma Piṭaka and other texts in Khmer script. The text in black ink has red intonation marks as a guidance for correct chanting. Central Thailand, 19th century. Shown here is an image of monks chanting. Thai folding book (samut khoi), 19th century, manuscript (The British Library)

Most Buddhists chant to help their daily life. Many people take the ‘refuges’, the protection of the Buddha, the teaching (dhamma), and the community of followers (sangha). They often commit to the five precepts too: undertakings not to harm others, not to steal, not to use the body for sexual activity that can harm self and others, not to lie, and not to become intoxicated. These support the ethical part of the eightfold path: right speech, action and livelihood. Following the precepts ensures the path is whole; they are seen as protective, so meditation and daily life will be safe and not cause harm or worry. All forms of Buddhism regard them as important.

Fragment of a manual on visualisation meditation practices in the Yōgavacara tradition in Pāli language in Khmer script. Thailand or Cambodia, 18th century (The British Library)

How can visualisation aid meditation?

Some forms of Buddhism, particularly in Tibet, China and Japan, teach visualisation as a means to meditation. The practitioner visualises an image of the Buddha, and feels its qualities arise inside them themselves. The way to do this is always taught by a teacher.

A 10th-century printed prayer sheet with an illustration of Amitābha Buddha. Sheets such as these were popular objects of devotion. Printed Prayer Sheet with an illustration of Amitābha Buddha, c. 10th century, woodblock-printed sheet (The British Library)

Sometimes visualisation practices focus on a figure known as a Bodhisattva, often portrayed as a god or goddess, who has postponed their own enlightenment to help and teach other beings how to be free from suffering. Offerings are made and sacred syllables (mantras) chanted.

Dhāranīs (charms or payers to ward off evil) are often placed in sacred statues or miniature stupas. The wooden miniature pagoda shown here contained four dhāranīs printed on paper. The pagoda has a carved, cylindrical cavity in the centre to hold the scriptures. One Million Pagoda Dharani, 764–770 C.E. (The British Library)

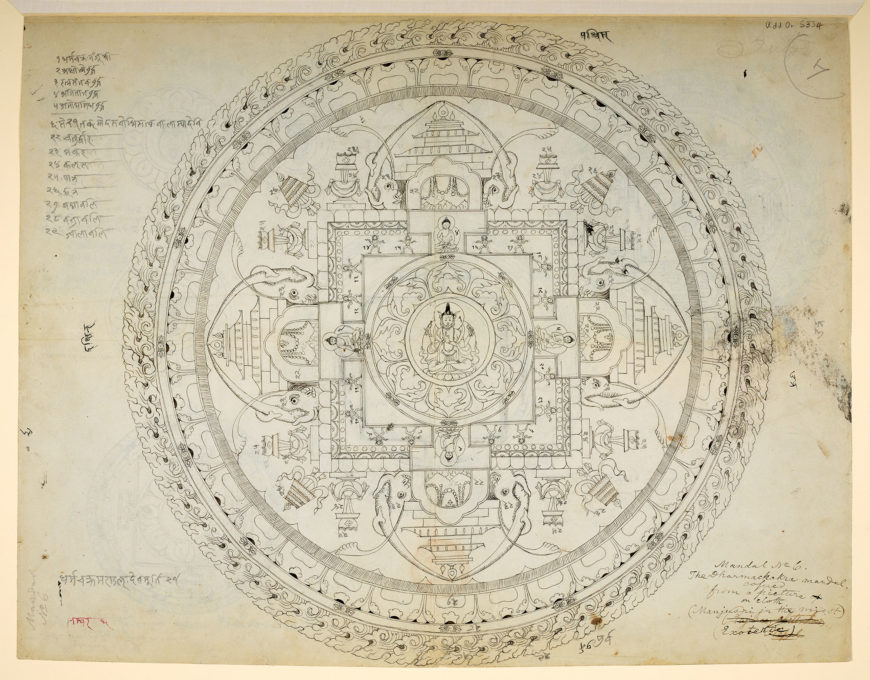

Visualisations often involve other supporting gods and deities, in a mandala (a circular design). The whole picture, with the circle of beings inside it, is protected by guardians of the four directions, who have an overview of the whole, and steadiness. Some say they balance the four elements of earth, water, air and fire within us. The mandala they guard sometimes depicts fierce and powerful deities. They symbolise various energies or aspects of our mind, that can be brought into harmony. In the centre, the Bodhisattva, or the Buddha, represents the possibility of stillness in all worlds. Then, it is important at the end of visualisations to thank the Bodhisattvas, and invite them to go.

Rajir Citrakar, Sheet drawn on both sides illustrating different types of Buddhist mandalas, c. 1820–1844, Nepal, ink on paper (The British Library)

All branches of Buddhism emphasise being ‘present’ in what you are doing at the time, and letting go of what you have just done: after meditation you need to return to normal life.

What is Zazen meditation?

Yet another form of meditation takes everything that is going on, and sits with it, coming to understanding through watching processes in the mind and body, sounds, touches, changing feelings. This kind of meditation is known as Zazen, and is practised by some schools of Buddhism from China, Korea and Japan.

As this summary suggests, there are many kinds of Buddhist meditations. All aim to balance us, and bring calm and insight. In early texts, the Buddha taught those that suited a particular person, and adapted it to their needs. Effective meditation practises do this now, and make sure that the practice suits the person, and that they are ready for each new stage as it comes along. All aspects of the eightfold path are important; all support one another and depend upon one another.

Written by Sarah Shaw

Dr Sarah Shaw teaches Buddhism and researches Buddhist texts and stories. She is a fellow of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, and a member of the Faculty of Oriental Studies and Wolfson College, University of Oxford. She teaches for the online MA in Buddhist Studies at the University of South Wales. She has published a number of books on meditation and Buddhist stories, including The Spirit of Buddhist Meditation, Introduction to Buddhist Meditation and the Penguin Jātakas. Her most recent book, Mindfulness: what it is and where it comes from, was published by Shambhala in August 2019.

The text in this article is available under the Creative Commons License.

Originally published by The British Library.