Latin American art: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 64

Art and Nationalism in 19th-century Latin America

In the early nineteenth century, battle cries for independence spread throughout Latin America (after hundreds of years of European control), including Mexico’s famous Grito de Dolores (September 16, 1810). But freedom came with new challenges. Revolutionaries and ordinary citizens alike asked: Who are we as a nation? What is our national identity? As a result, Latin Americans witnessed tremendous political, cultural, social and artistic transformations.

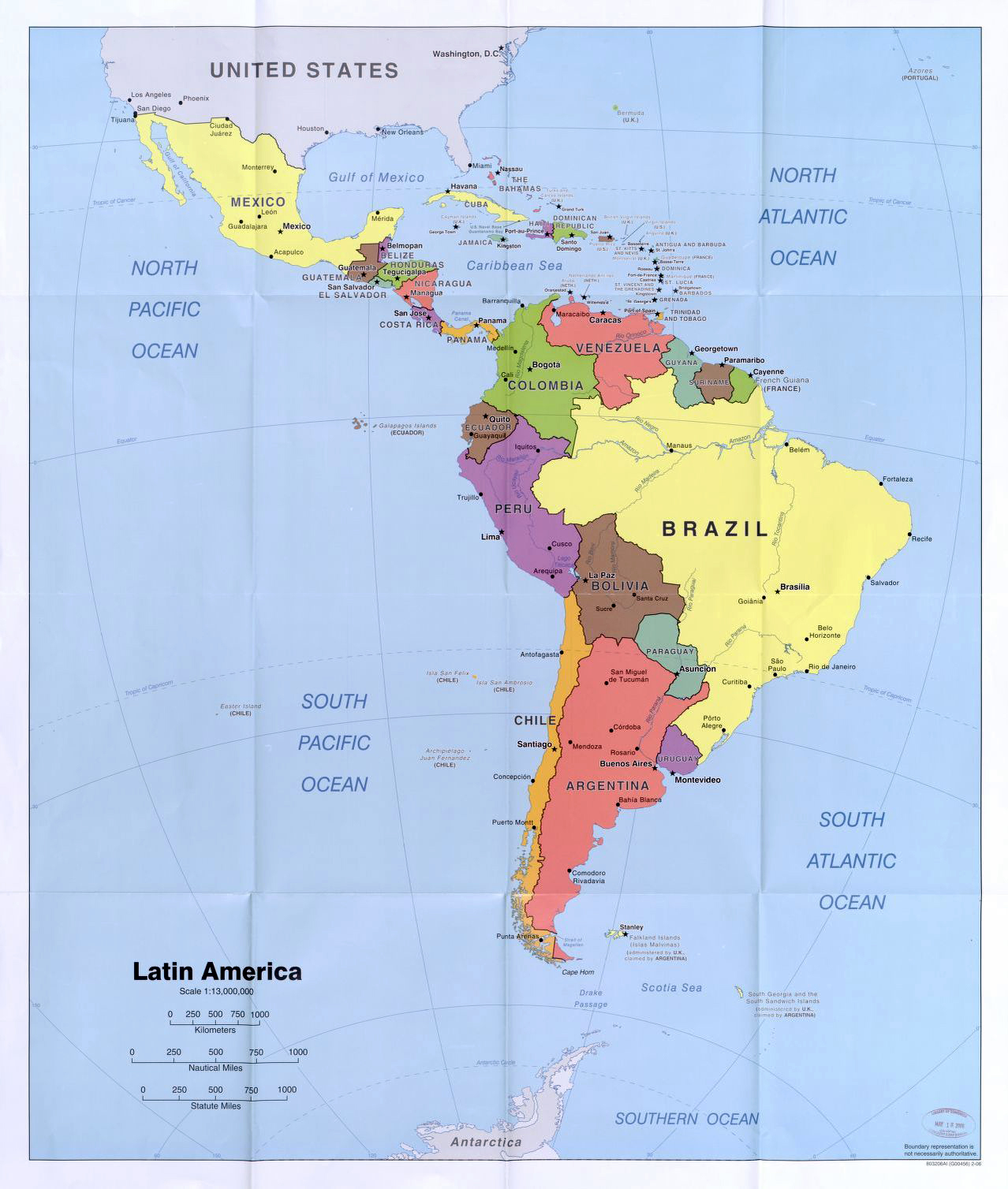

Map of Latin America, published Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency (Library of Congress)

Formerly known as viceroyalties (which were subject to rule by the Spanish Crown), newly independent countries began to emerge, including Mexico, which was liberated in 1821. Many of these countries had been freed by Creoles like Simón Bolívar, who helped secure independence for Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela and José de San Martín, the liberator of Argentina, Chile, and Peru. No longer subject to Spanish rule, these countries were now confronted with the daunting task of articulating a sense of national identity that could make sense of the colonial past and carve an independent path forward. Early expressions of nationalism (loyalty to a nation) focused primarily on creating monuments to revolutionary heroes, though we also see it in the people and narratives depicted in art.

Site of the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City since 1791 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Art schools that had in some cases been established under Spanish rule, helped to articulate a national artistic tradition. These academies were informed by traditional models of art education, and emulated the European art academies. Art academies were also hubs in a global network, since students and professors traveled abroad and schools attracted foreign artists. This in turn fostered artistic traditions that became more varied, and more modern. This chapter explores both these formal institutions and the international transatlantic artists who shaped nationhood in post-independent Latin America.

Read introductory essays about 19th-century Latin America

/3 Completed

Art Academies: A Bastion of Classicism

José María Obregón, The Discovery of Pulque, 1869, oil on canvas, 189 x 230 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, INBA (MUNAL), Mexico City)

At first, official art academies defined the national artistic discourse, replacing colonial modes of artistic education, like guild systems and artist workshops, which had focused primarily on religious subject matter and worked in the service of the church. With political independence came both a stylistic and thematic shift. Artists trained in academies, for example, depicted the heroism and patriotism of their fight for independence by painting portraits of the liberators and martyrs who had become national heroes, and by depicting pivotal battles in the fight for independence.

Manuel Vilar, Tlahuicole, the Tlaxcaltecan General, Fighting in the Gladiatorial Sacrifice, 1851, painted plaster, 216 x 135 x 132 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, INBA (MUNAL), Mexico City, photo: Steven Zucker)

The Academy of San Carlos was the earliest art academy of the Americas. It was established in Mexico City in 1785, thirty-six years before independence. It trained emerging painters, sculptors, and architects in the Greco-Roman classical tradition, where artists were encouraged to study and idealize the human body. It also supported their professional careers, introduced them to exhibition and travel opportunities, and most importantly, served as an example for future art schools in the region, such as the Cuban Academy of San Alejandro founded in 1818.

At the Academy of San Carlos, artists such as Manuel Vilar adapted the heroism and idealization of classical art to fit the Mexican past. This resulted in a depiction of the Tlaxcaltecan warrior as a heroic and idealized figure, a sharp contrast to earlier depictions that often displayed victimized and enslaved Indigenous peoples. Vilar’s sculpture not only “classicized” the Indigenous past (by making an Indigenous Nahua warrior in the style of an ancient Greek or Roman sculpture), but also introduced the subject of the nude to Latin American art. The figure was not simply naked, meaning unclothed, but rather nude, implying that his nakedness was done in the service of art and for greater symbolic meaning.

Felipe Santiago Gutiérrez, The Huntress of the Andes, c. 1891, oil on canvas, 102 x 159 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, INBA)

However, it was not until the late nineteenth century that the practice of painting, drawing, and sculpting from the nude gained currency across Latin America. And even then, the female nude encountered resistance in this deeply conservative Catholic region. Even in the late 19th century, the Latin American art establishments rejected allusions to sexuality, even if the nude was mythological, as in the case of Huntress of the Andes (1891), or biblical, as in the case of Levite Woman from the Ephraim Mountains (1899).

Epifanio Garay, Levite Woman from the Ephraim Mountains, 1899, oil on canvas, 139 x 198.5 cm (National Museum of Colombia, Bogotá)

It was clear to emerging Latin American artists at this time that the academies were conservative and rooted in tradition (as they were in Europe); and so, in order to seek out more modern styles and subjects, as well as art commissions, they would need to travel abroad.

Read essays and watch videos about art academies

The Academy of San Carlos: The earliest art academy in the Americas, founded in 1785 under the leadership of Spanish engraver Jerónimo Antonio Gil.

Read Now >

Manuel Vilar, Tlahuicole: This sculpture was the first at the Academy to explicitly depict the pre-Hispanic past.

Read Now >

The challenge of the nude in 19th-century Latin American painting: Latin American artists who wished to excel in their ability to paint the nude had to seek an artistic education either in Mexico or abroad in cities like Paris or London.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Costumbrismo: In Search of Nationalism

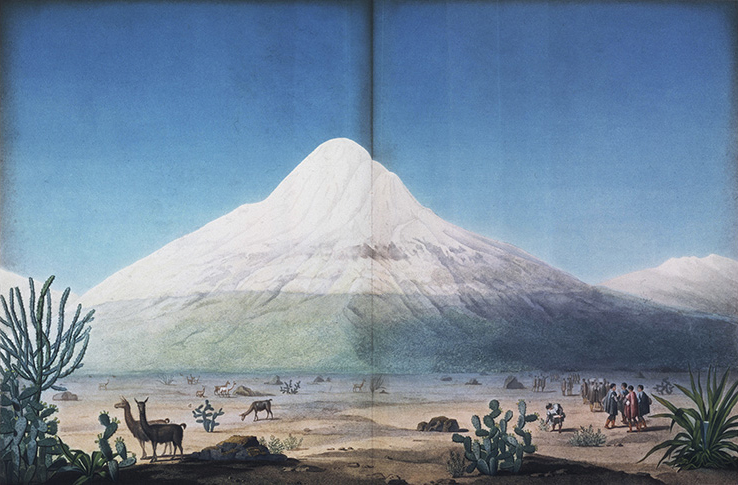

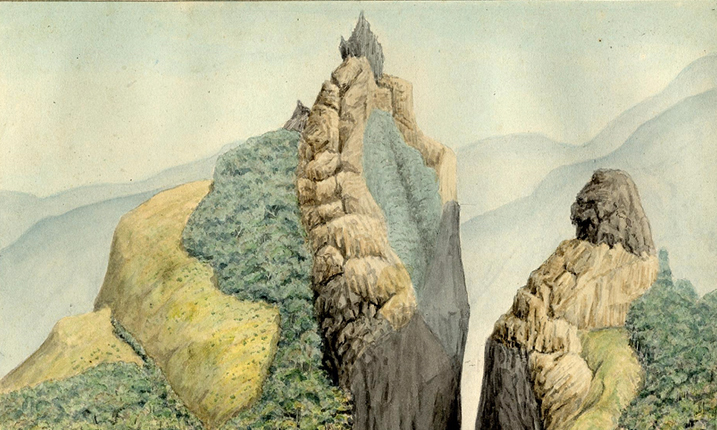

Alexander von Humboldt, “Chimborazo Seen from the Tapia Plateau,” Ecuador, hand-colored engraving, in Vues des Cordillères et monuments des peuples indigènes de l’Amérique, 1810

After independence, and against the backdrop of these official academies, Latin American countries entered another era of global exchange, one that echoed the exchanges of the colonial era, a period characterized by an influx of foreigners and an exodus of locals. Foreign scientists, writers, and artists arrived to explore and document what they saw in Latin America, many following in the footsteps of German scientist Alexander von Humboldt and which included the U.S. painter Frederic Edwin Church. They documented the flora and fauna well as its people, traditions, local folklore, and genre scenes—a practice known as costumbrismo.

Rafael Troya, Cotopaxi, 1874, oil on canvas, 93 x 161 cm (Museo ‘Guillermo Perez Chiriboga’ del Central de Ecuador)

Local artists also surveyed and documented the landscape of these newly liberated countries, like Joaquin Pinto and Rafael Troya, who captured the volcanic peaks of their native Ecuador.

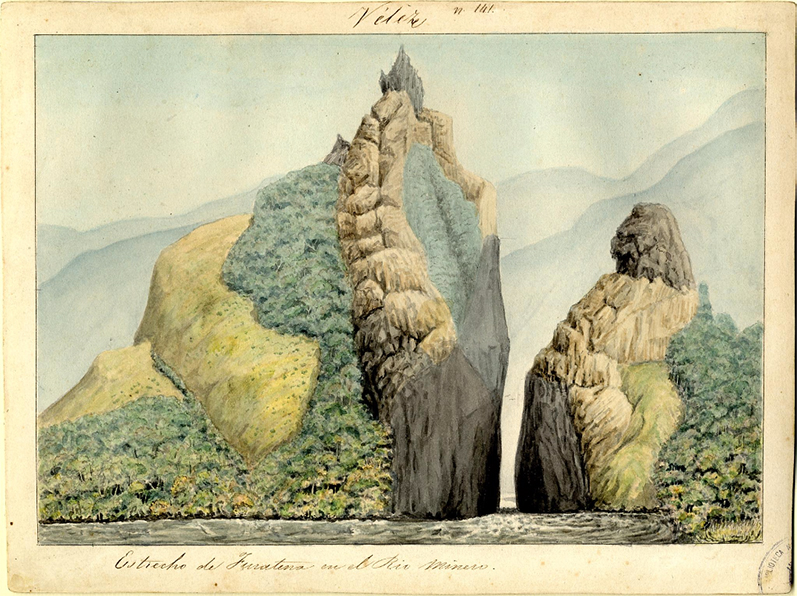

Carmelo Fernández, Province of Vélez, The Strait of Furatena in the Minero River, 1850-51, watercolor on paper (Colombian National Library)

In Colombia, the Comisión Corográfica, which involved artists like Carmelo Fernández, resulted in the creation of some of the first maps and atlases of the region. However, even this scientific enterprise included the depiction of local types and costumes, demonstrating the blurred boundaries between geographical surveys and costumbrismo.

Felipe Santiago Gutiérrez, The Young Indian’s Farewell, 1876, oil on canvas, 82 x 92 cm (Private Collection, Mexico City)

Felipe Santiago Gutiérrez defined nationalism through the people and customs of his native Mexico. In his depiction of everyday subjects, like The Young Indian’s Farewell, Gutiérrez captured the spirit of costumbrismo, as seen in their traditional Mexican attire and racial diversity. However, the crisp style and theatrical composition of this painting reflects Gutiérrez’s training at the academy and abroad, which in turn parallels the narrative itself, the story of a rural Indian boy who leaves for the big city. Indeed, both Gutiérrez and the young Indian speak to the larger trend of cosmopolitanism, the desire of Latin Americans to transcend provincialism and belong to a larger world culture, either by going to Mexico City or Paris.

Read essays and watch videos related to costumbrismo

Early Scientific Exploration in Latin America: European explorers enhanced knowledge of the new world, but their efforts were soured by an air of re-conquest.

Read Now >

Frederick Edwin Church, Cotopaxi: Its detailed style and interest in natural wonders reflects a fascination with the great variety of the environment as well as the emerging understanding of the earth’s geological evolution.

Read Now >

Carmelo Fernández, The Strait of Furatena in the Minero River: Nine years and three different artists later, the Chorographic Commission had produced both an Atlas of Colombia and many watercolor drawings.

Read Now >

Felipe Santiago Gutiérrez, The Young Indian’s Farewell: Gutiérrez wanted to create art that would change the perception and status of the artist in Mexico.

Read Now >

Francisco Oller y Cestero, The Wake: This monumental painting shows a Puerto Rican rural tradition, the sad yet celebratory wake for a small child.

Read Now >/6 Completed

Transatlantic Voyages: Artistic Pilgrimages to Paris

While some Latin American artists traveled across the continent, others traveled abroad to Europe in search of more opportunities, whether at art schools or exhibition venues. The establishment of art academies, together with the movement of ideas and artists across the Atlantic, introduced a sense of internationalism that came to define the cultural and artistic standards of the nineteenth century and early 20th century.

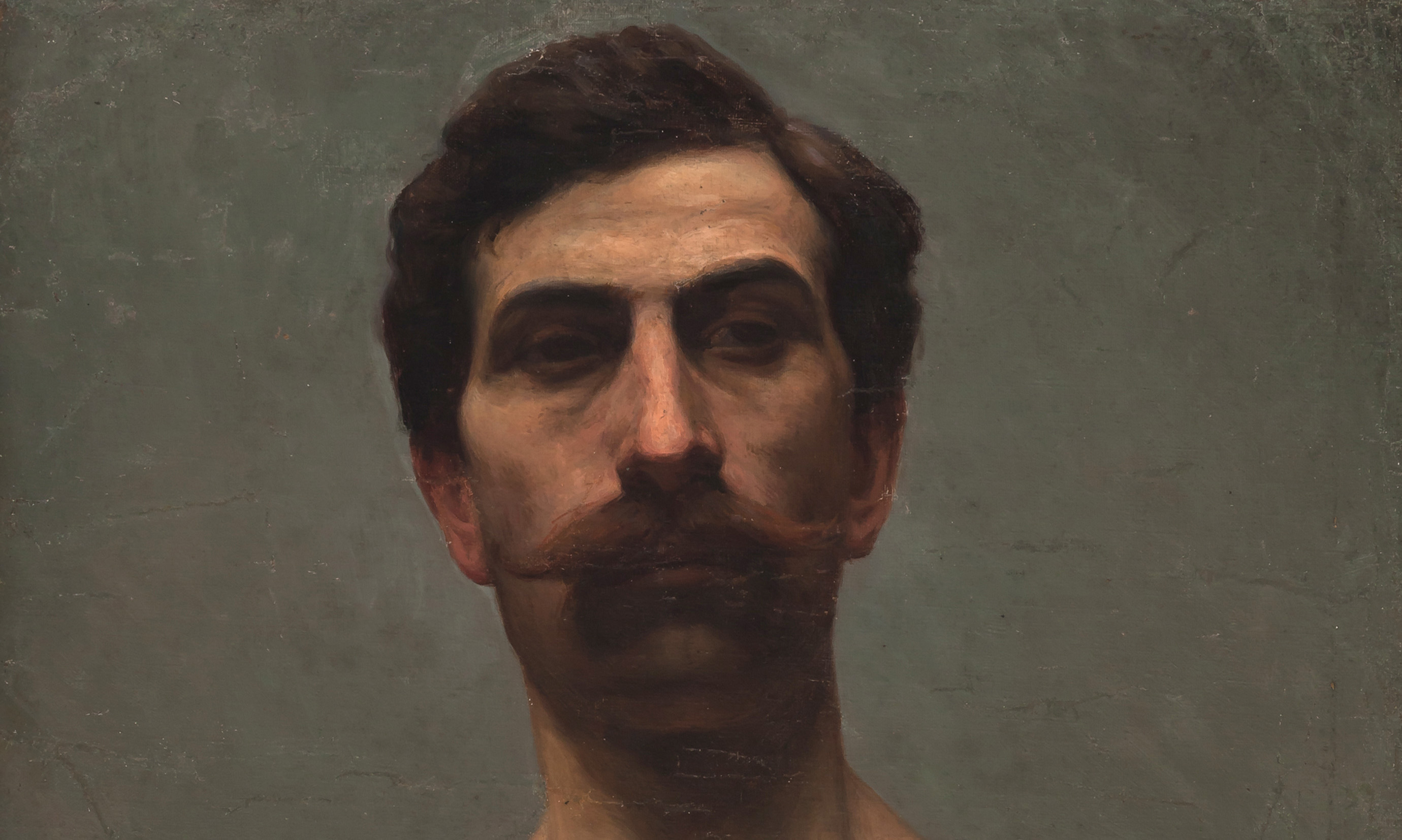

A bust of Epifanio Garay in Bogotá, Colombia (photo: Felipe Restrepo Acosta, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Latin American artists mostly traveled to Paris, where they encountered an art scene unlike the one they had left behind, in that it was full of options, in the form of alternative art studios, supportive art critics, and a diverse artistic community. Latin American artists felt energized by their trips abroad, and upon their return to Latin America, they encountered new professional opportunities at the academy and beyond, but also a more conservative audience.

Francisco Oller, Hacienda La Fortuna, 1885, oil on canvas, 66 x 101.6 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Nevertheless, the lessons learned abroad quickly made their way back to Latin America, with painters like Epifanio Garay (Colombia) and Eduardo Sivori (Argentina) who championed the practice of drawing and painting from the live model and the depiction of the female nude in art. Others, like Francisco Oller (Puerto Rico) and Esteban Chartrand (Cuba) blended the loose brushwork and natural light of French Impressionism with national symbols like the palm tree and sugar plantation. Their landscapes evoked a sense of national identity that was rooted in the rural landscapes of the Caribbean.

Read essays about transatlantic voyages

Latin American artistic pilgrimages to Paris: In the 19th century, Latin American artists eagerly traveled to this artistic capital, in part because of the absence of an official art school, established art market, or proper exhibition venues back home.

Read Now >

Landscape Painting in Nineteenth-Century Latin America: Artists developed interests in painting the local landscape as a way to create a sense of pride in their country’s past, present, and future.

Read Now >

Francisco Oller, Hacienda La Fortuna: Oller produced his painting as Puerto Rico experienced an intense transition at the end of the Spanish-American war.

Read Now >/3 Completed

International Exhibitions and Cosmopolitanism

Crafting a sense of national identity at home was a challenge, however, once abroad, artists sought to represent their national identity through their art for an audience that was largely indifferent and often misinformed about Latin America. Myths of Latin America abounded in Europe, including those of a “primitive” culture stuck in the past, or of an untamed and wild landscape. Artists encountered stereotypes that underestimated their reputations, professionalism, and internationalism (for example, both Francisco Laso (Peru) and José Maria Velasco (Mexico) were world travelers).

Francisco Laso, Inhabitant of the Cordillera of Peru, 1855, oil on canvas, 138 x 88 cm (Museo de Arte de Lima)

World fairs (also known as universal exhibitions), were popular attractions in the nineteenth century, offering countries the opportunity to compete on an international stage while showcasing their talent and ingenuity. At the Universal Exhibition of 1855, held in Paris, Laso proudly exhibited two canvases, one of which, The Inhabitant of the Cordillera of Peru, was met with criticism. French critics renamed the painting, Indian Potter, simplifying the narrative and undermining the painting’s intent, which was to demonstrate the marginalization and struggle of the Indigenous people of Peru. At least overseas, Laso’s dignified depiction of an Amerindian man was not as successful as the more subtle work of Velasco.

José María Velasco, The Valley of Mexico from the Santa Isabel Mountain Range (Valle de México desde el cerro de Santa Isabel), 1875, oil on canvas, 137.5 x 226 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, INBA, Mexico City, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An internationally renowned artist who garnered awards at the universal exhibitions of 1876 (Philadelphia) and 1889 (Paris), Velasco painted multiple landscape views of the iconic and historic Valley of Mexico. In the monumental style of Eugenio Landesio, his teacher at the Academy of San Carlos, Velasco presented expansive, almost panoramic views of this area. Velasco’s The Valley of Mexico from the Santa Isabel Mountain Range (1875), for example, allows one to see both the remains of the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan and the colonial site of the Virgin of Guadalupe’s miraculous apparition. International viewers applauded these monumental and romantic landscapes, in which the land, sky, and botany triumphed over Mexico’s indigenous and colonial history.

For Latin American artists who didn’t bear the brunt of international criticism (such as Laso in Paris), they nevertheless confronted conservative critics back home (such as Garay in Bogotá). The search for national identity played out differently according to artist and country, but they all shared in the experience of giving meaning to their indigenous and colonial past while using the lessons of the academy and abroad to forge a new artistic path forward.

Read an essay about Velasco

José María Velasco, The Valley of Mexico from the Santa Isabel Mountain Range: This painting represents an important period in the development of Mexico’s national identity and an important chapter in the history of Mexican art.

Read Now >/1 Completed

Key questions to guide your reading

What were the most significant changes that came after independence?

How did artists depict their prehispanic and colonial past?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat were the most significant changes that came after independence?

How did artists depict their prehispanic and colonial past?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

academy

cosmopolitanism

costumbrismo

creole

history painting

nationalism

Neoclassicism

World Fair

Learn more

Read about the Spanish viceroyalties in the Americas

Learn about the Virgin of Guadalupe

Learn more about the historical backdrop of the Mexican-American War