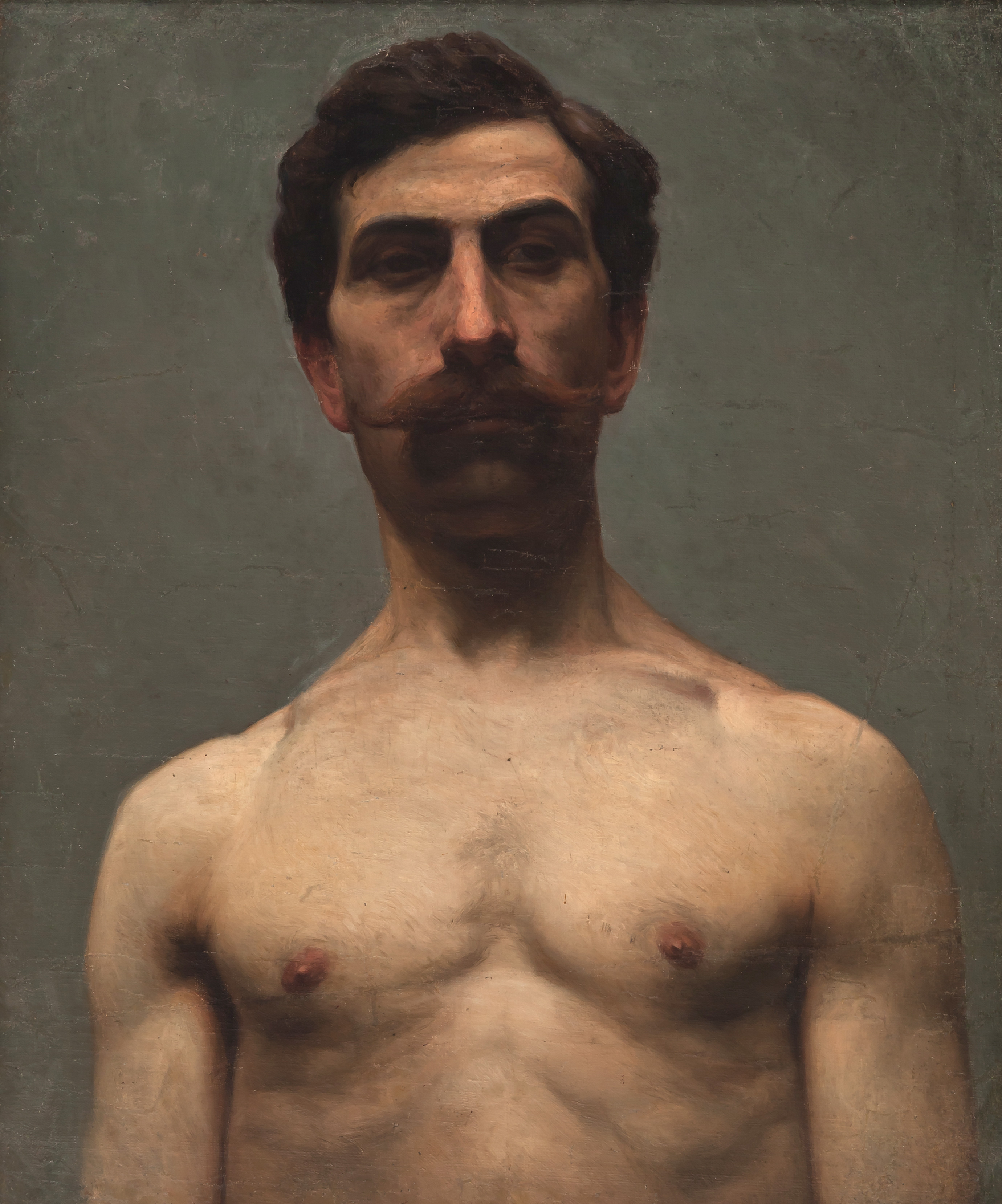

Francisco Antonio Cano, Model of the Académie Julian, c. 1898, oil on canvas, 61 x 51 cm (Colección del Banco de la República, Bogotá, Colombia)

Artists have often studied the nude either by copying it from prints, manuals, illustrations, and sculptures, or directly from a live model. A common practice in European and U.S. art academies of the 19th century, the practice of drawing from life was not accepted in most Latin American art academies (with the exception of the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City) until the early twentieth century. Even then, it was largely restricted to male students. The nude was considered morally offensive among religious and political conservatives throughout much of Latin America, and even in the United States, and so it became a sensitive subject for artists to depict. [1] For this reason, Latin American artists who wished to excel in their ability to paint the nude had to seek an artistic education either in Mexico or abroad in cities like Paris or London.

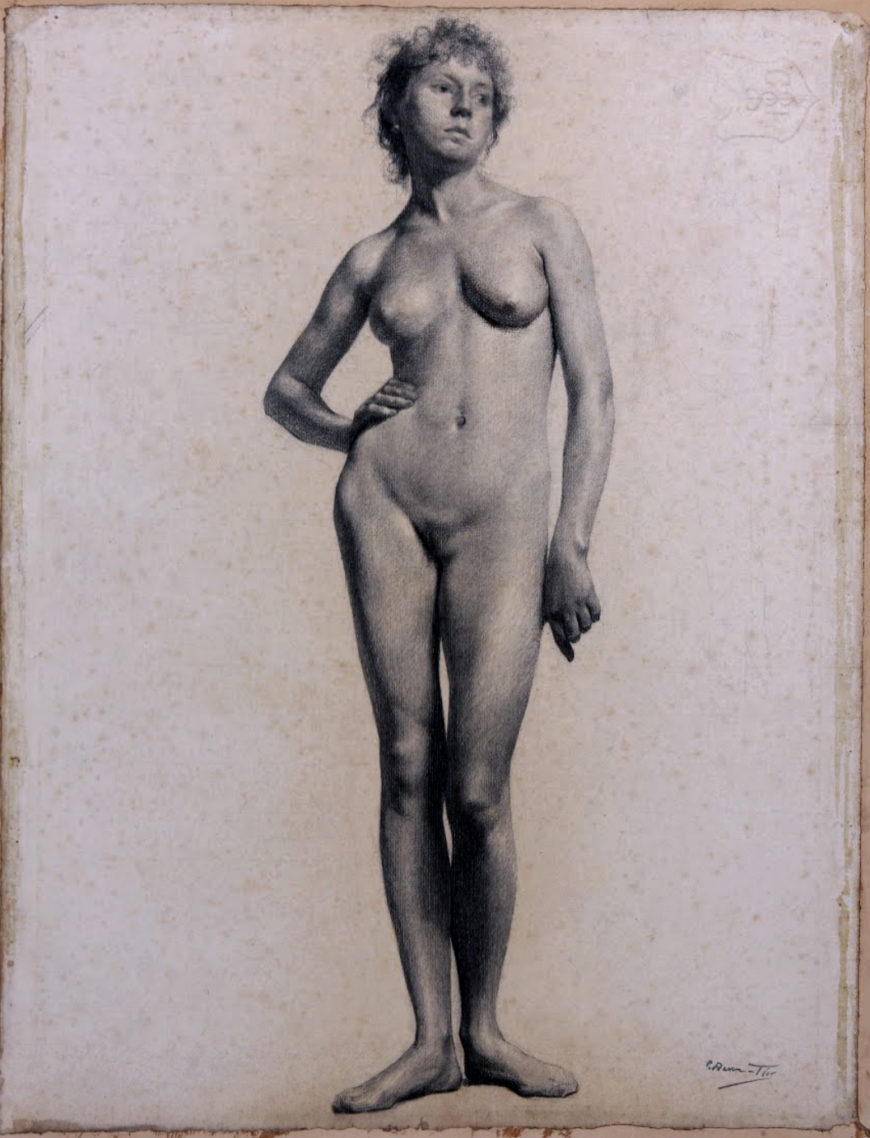

Carlos Baca-Flor, Female Academy, c. 1893-95, charcoal on paper, 48 x 62.5 cm (MALI, Museo de Arte de Lima)

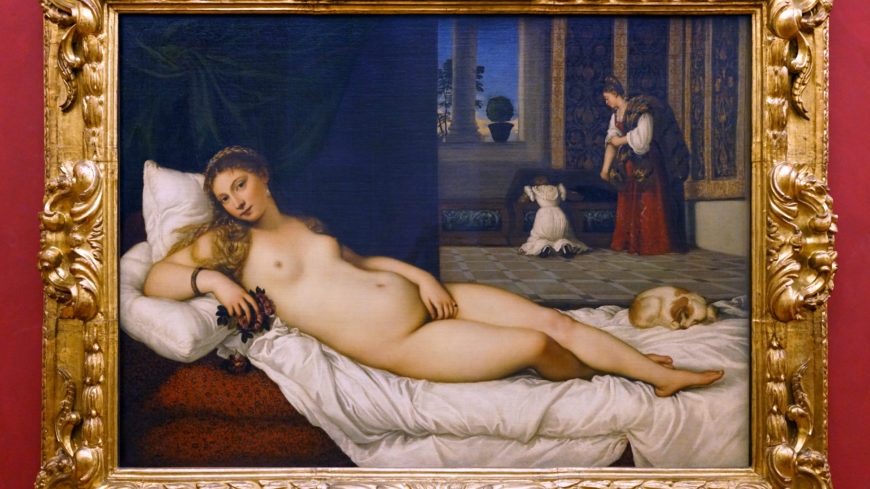

At the Académie Julian in Paris, the practice of life drawing was considered integral to an artistic education. It was at this art school that Peruvian Carlos Baca Flor excelled in the study of the nude model and Colombian artist Francisco A. Cano was first exposed to it. Cano painted numerous nude studies, formally known as académies, and among them Model of the Académie Julian. In this painting, we see a bust-length, nude man, who looks directly towards viewer. Presented against a stark background and illuminated by natural light, Cano captures the subtle curves of the human body through careful chiaroscuro (shading). While Cano’s nude studies reflected a considerable part of his artistic education abroad, back home these works were never exhibited, though there were sometimes private commissions. [2]

Felipe Santiago Gutiérrez, The Huntress of the Andes, c. 1891, oil on canvas, 102 x 159 cm (Colección Andres Blaisten)

The mythological nude

On the few occasions that nude paintings were publicly shown, the subject was almost always represented in the context of mythology. Mexican artist Felipe Santiago Gutiérrez’s Huntress of the Andes and Chilean Valenzuela Puelma’s Nymph of Cherries are two examples. Gutiérrez’s painting alludes to Diana, the Goddess of the hunt, who is set against the backdrop of the Andes Mountains. While Gutierrez situates her in the Andean landscape, with snow covered peaks in the background, it is the female nude that dominates the picture plane. Diana is not presented in the act of hunting, but rather at rest, her body stretched diagonally across the animal pelt and her hand placed over her bow and arrow.

Alfredo Valenzuela Puelma, Nymph of Cherries, c. 1889, oil on canvas (Pinacoteca de la Universidad de Concepción, Chile)

Puelma, who had trained in the studio of French painter Jean Paul Laurens, depicts a nymph, a mythological spirit of nature usually depicted in a female guise. Here, the nymph is also depicted in a reclining position, as was common with female nudes painted by male artists, from as early as the Italian Renaissance (by artists like Titian) and throughout the nineteenth century (as in the case of Manet). The nymph provocatively looks out towards the viewer, her mouth partly open and her hand gesturing to the scattered cherries in the foreground. Her seductive pose and the tantalizing nature of the sweet cherries transform this female nude from a mythological subject, into an eroticized one. It was not enough to simply shroud the female nude in Classical mythology (or in some cases Biblical narratives, as in the case of Colombian Epifanio Garay), male artists were also expected to minimize her eroticism, demonstrating how the female nude, whether mythological or not, relied on a different set of viewing standards that sought to transcended physical desire and linked the ideal nude to spiritual beauty. [3]

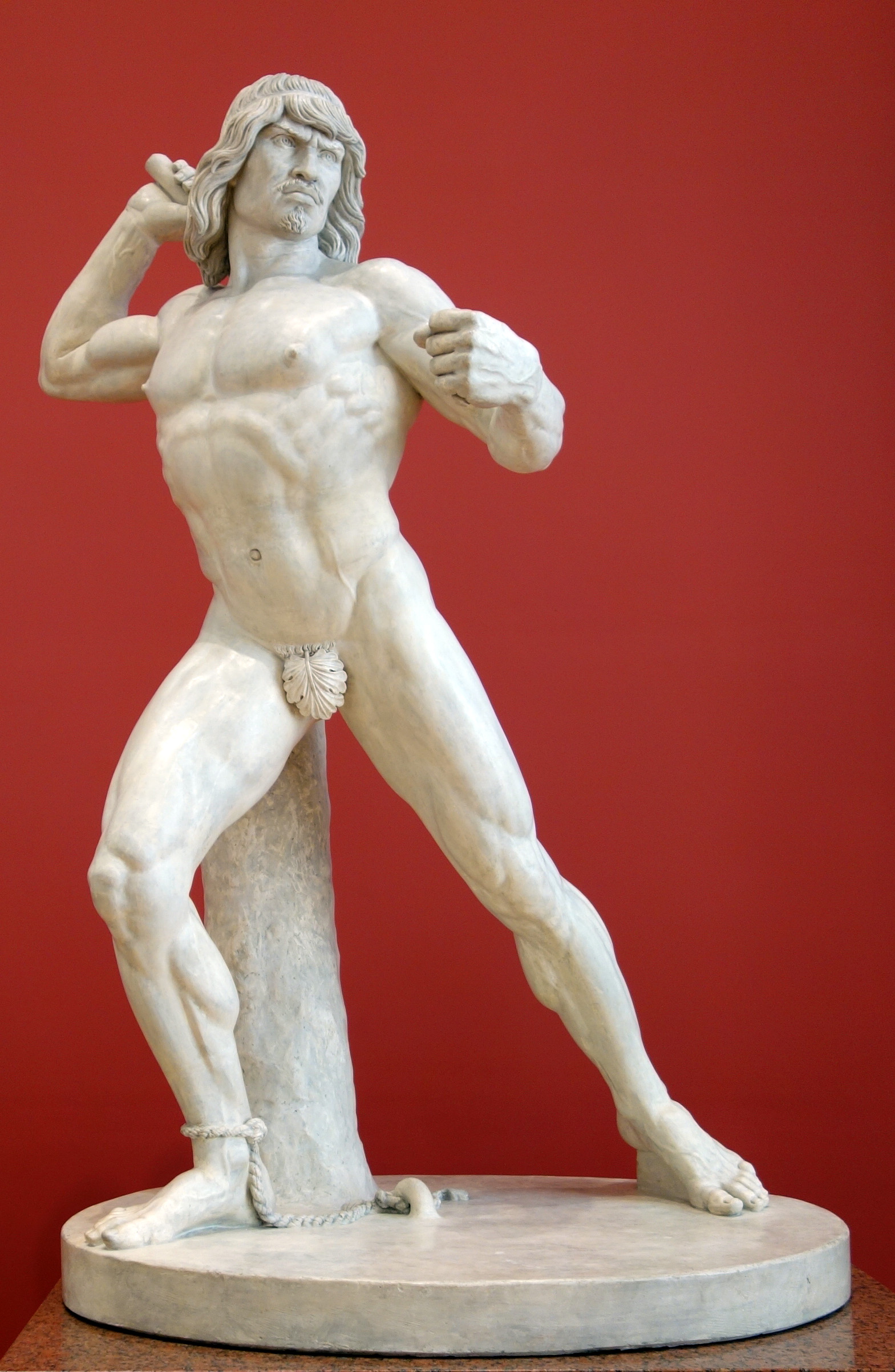

Manuel Vilar, Tlahuicole, the Tlaxcaltecan General, Fighting in the Gladiatorial Sacrifice, 1851, painted plaster, 216 x 135 x 132 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City)

Differing standards

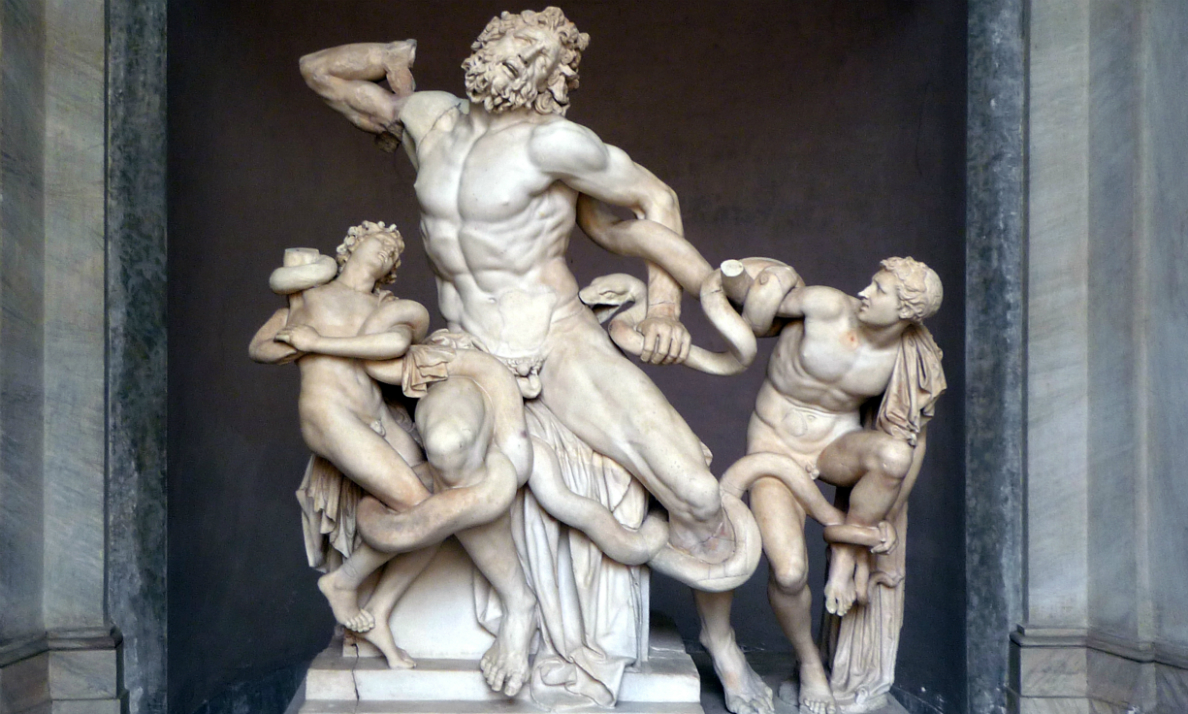

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums)

Not only the gender of the artist, but also that of the model played an important role in the reception of many of these artworks. The male nude was not met with as much concern as the female nude. Spanish artist Manuel Vilar’s The Tlaxcalan General Tlahuicole Doing Battle on the Gladiator’s Stone of Sacrifice and even Cano’s Model of the Académie Julian do not show explicit nudity, but they nevertheless feature bare chested men. Vilar’s Tlaxcalan general relies heavily on exposed and indeed exaggerated musculature, a reference to the Aztec warrior’s heroic death as a martyr. Vilar based Tlahuicole on the ancient Greek statue of Laocoön and his Sons, demonstrating the strong influence of Graeco-Roman Classicism on the subject of the nude. Despite its subject matter and artistic influence, Vilar covers the figure’s genitalia with a leaf— an overt reference to the controversial nature of the nude.

A path towards modernism

Argentine Eduardo Sívori, who also trained under Jean Paul Laurens, pushed his luck even further, when he exhibited The Maid’s Wakeup in 1887 in Buenos Aires. Devoid of any historical or mythological narrative, Sívori depicted a naked, rather than nude woman, and a working woman, rather than an idealized one. The casual, unheroic nature of her nakedness, and the humility of her bedroom differed greatly from the classicizing nudes of other Latin American artists. In portraying a common woman, rather than an ideal one, and in not providing any legitimate reason for her nakedness, Sívori pushed the limits of acceptability. After exhibiting The Maid’s Wakeup to positive acclaim in Paris, at the Salon des Artistes Français of 1887, he encountered an entirely different response in Buenos Aires. One critic from the conservative newspaper, El Censor, protested not only the woman’s nudity, but also the fact that she was a simple maid, rather than a goddess. [4] Despite these criticisms, Sívori and others established a precedent of challenging moral conventions, ultimately paving a path towards modernism in Latin America. [5]

Notes:

[1] In the United States, the practice of live modeling was controversial at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and especially under the instruction of Thomas Eakins. See Amy Werbel, Thomas Eakins: Art, Medicine and Sexuality in Nineteenth Century Philadelphia (Yale University Press, 2008).

[2] For more information, see Juan Camilo Escobar Villegas, Francisco Antonio Cano: 1865-1935 (Museo de Antioquia, 2003): 114-129.

[3] Maya Jiménez. “A Cosmopolitan Ambition: La Regeneración and the French Academic Nude in 19th-Century Colombia”. H-ART. Revista de historia, teoría y crítica de arte, no. 7 (2020): 159-176. https://doi.org/10.25025/hart07.2020.09

[4] Laura Malosetti, Los primeros modernos: Arte y Sociedad en Buenos Aires a fines del siglo XIX (El Fondo de Cultura Económica de México, 2001): 77.

[5] Maya Jiménez, “Modernism and the Nude in Colombian Art,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring13/jimenez-modernism-and-the-nude-in-colombian-art (accessed August 16, 2021).

Additional resources:

Read about the history of the nude in Western art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art