Virgin of Guadalupe, late 17th century, 190 cm high, oil paint, gilding, and mother of pearl on panel (Franz Mayer Museum, Mexico City)

Loving mother. Devoted wife. Ideal woman. Queen of Heaven.

Who could ever be this perfect? For Christians, the Virgin Mary carries all these titles, and she is often celebrated in art as a mother, wife, and queen. With Spanish colonization of the Americas, devotion to the Virgin Mary crossed the Atlantic.

Virgin of Guadalupe, 16th century, oil and possibly tempera on maguey cactus cloth and cotton (Basilica of Guadalupe, Mexico City; photo: Fr Lawrence Lew, O.P., CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The conquistador Hernán Cortés even carried a small statue of the Madonna with him as he searched for gold and encountered the Indigenous peoples of Mexico. After the defeat of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1521 and the establishment of the Spanish Viceroyalty of New Spain (Spanish rule in Mexico, Central America, and part of the U.S., 1521–1821), the Virgin Mary became one of the most popular themes for artists. One Marian cult image eventually became more popular than any other however: the Virgin of Guadalupe, also known as La Guadalupana. Her image is found everywhere throughout Mexico today, gracing churches, chapels, homes, restaurants, vehicles, and even bicycles.

Imagery from the Book of Revelation and the Song of Songs

Virgin of Guadalupe, 16th century, oil and possibly tempera on maguey cactus cloth and cotton (Basilica of Guadalupe, Mexico City; photo: Ari Helminen, CC BY 2.0)

Many people consider the original image of Guadalupe to be an acheiropoieta, or a work not made by human hands, and so divinely created. Some consider the image the product of an Indigenous artist named Marcos Cipac (de Aquino), working in the 1550s. In the original image, still enshrined in the basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City today, Guadalupe averts her gaze and clasps her hands together in piety. She stands on a crescent moon, and is partially supported by a seraph (holy winged-being) below. She wears Mary’s traditional colors, including a brilliant blue cloak over her dress. Embroidered roses decorate her rose-colored dress. Golden stars adorn her cloak and a mandorla of light surrounds her.

The image of Guadalupe relates to Immaculate Conception imagery, which drew aspects of its symbolism from the Book of Revelation and the Song of Songs. For instance, the Book of Revelation describes the Woman of the Apocalypse as “clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head.” In the Guadalupe image, twelve golden rays frame her face and head, a direct reference to the crown of stars.

Ashen skin

Guadalupe’s ashen skin is the subject of some discussion. It is possible that she represents an Indigenous Madonna. However, the Virgin of Guadalupe in Extremadura, Spain, after whom Mexico’s Guadalupe is named, is a black-skinned Madonna—a direct reference to Mary’s beauty based on a passage from the Song of Songs: “I am black but beautiful.” Black Madonnas were popular long before Guadalupe’s appearance in Mexico, and so it is possible that her ashen skin situates her within this pre-existing tradition.

Virgin of Guadalupe, 16th century, oil and possibly tempera on maguey cactus cloth and cotton (Basilica of Guadalupe, Mexico City; photo: Fr Lawrence Lew, O.P., CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Seeing her today

Today, millions travel annually to her basilica to glimpse the original image, which visitors see while zooming beneath it on a conveyor belt. The original shrine devoted to Guadalupe, on a hill above the basilica, marks the site of her initial miraculous appearance.

Her miraculous revelation to Juan Diego

The story associated with her miraculous revelation varies depending on the author, but the general story goes something like this: In December 1531, a converted Nahua man named Juan Diego was on his way to mass. As he walked on the hill of Tepeyac(ac), formerly the site of a shrine to the Aztec mother goddess Tonantzin, Guadalupe appeared to him as an apparition, calling him by name in Nahuatl, the language of the Nahua. According to one textual account written in Nahuatl, Juan Diego described her as dark-skinned, with “Garments as brilliant as the sun.” She requested that Juan Diego ask the bishop, Juan de Zumárraga, to construct a shrine in her honor on the hill. After recounting the story, the bishop did not believe Juan Diego and requested proof of this miraculous appearance. After speaking again with Guadalupe on two other occasions, she informed Juan Diego to gather Castilian roses—growing on the hillside out of season—inside his tilma, or native cloak made of maguey fibers, and bring them to the bishop. When Juan Diego opened his tilma before Bishop Zumárraga the roses spilled out and a miraculous imprint of Guadalupe appeared on it. Immediately, Bishop Zumárraga began construction of a shrine on the hill.

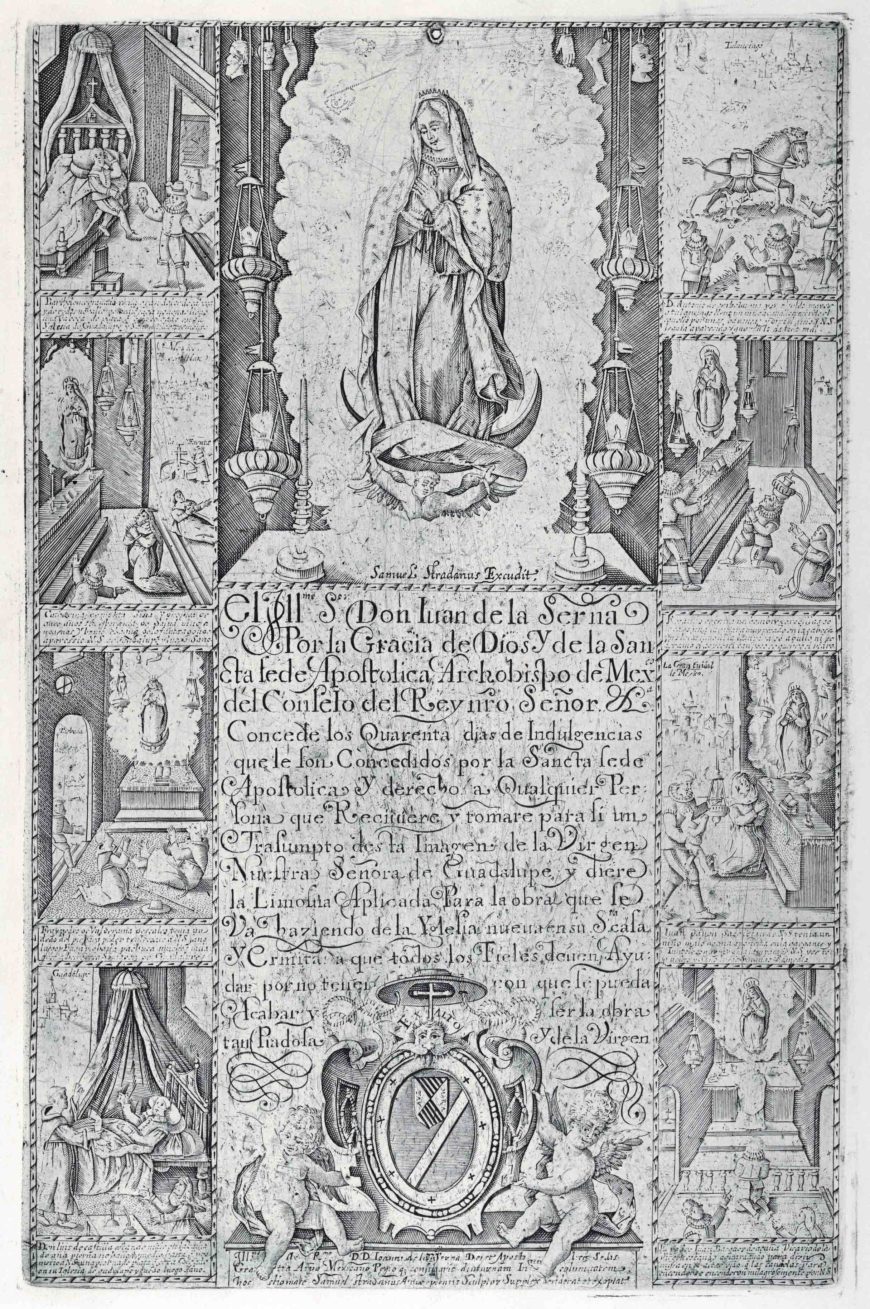

This engraving depicts the Virgin of Guadalupe at the top of the page. The borders of the print incorporate small scenes narrating miracles of the Virgin. Samuel Stradanus, Indulgence for donation of alms towards the building of a Church to the Virgin of Guadalupe (modern facsimile impression), 1608 (facsimile 1930–40), engraving, 43 x 28 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Devotion to Guadalupe

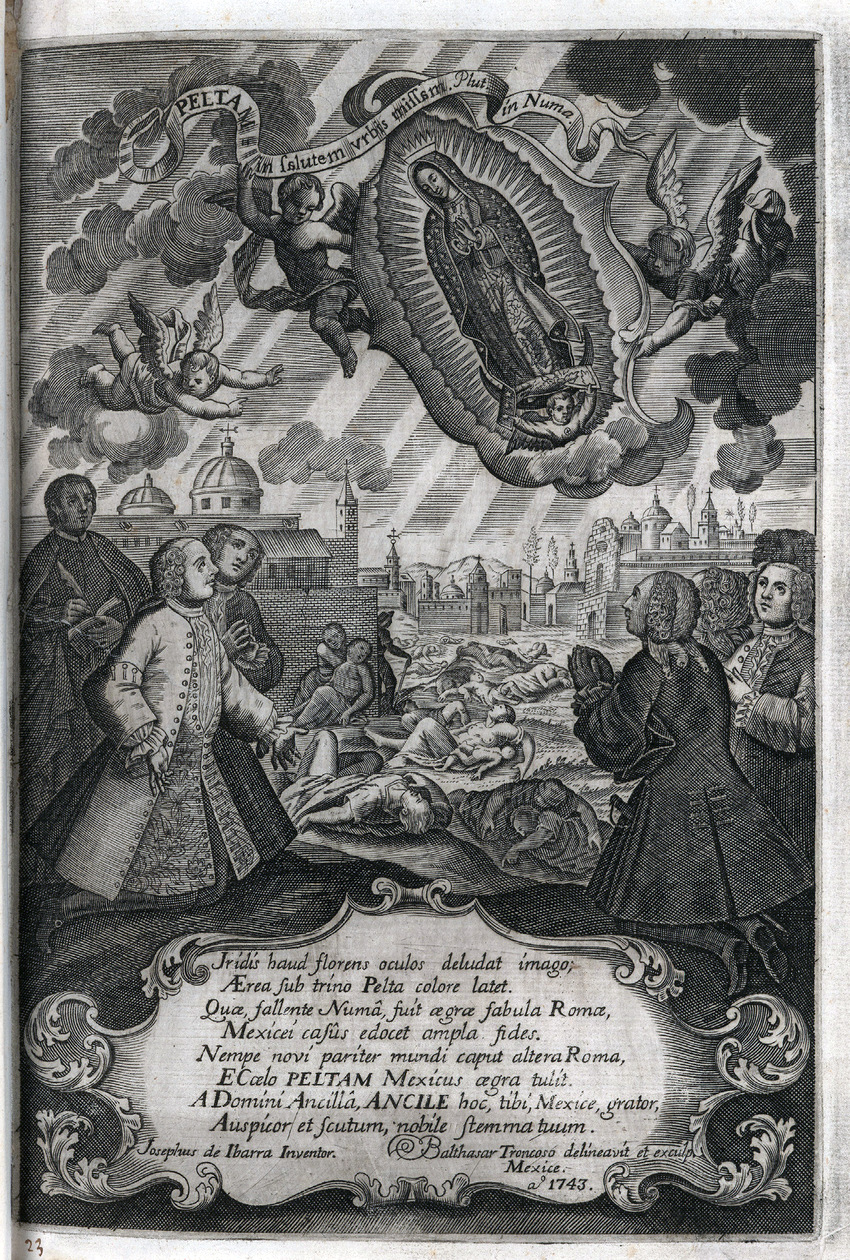

Initially, devotion to Guadalupe was primarily local. Yet veneration of Guadalupe increased, especially because people attributed her with miraculously interceding on their behalf during calamitous events. For instance, she was thought to assist in ending a flood in Mexico City in 1629 and an epidemic that ravaged the population of the capital between 1736–37. After the 1737 epidemic subsided, Mexico City declared her patron of the city. In 1746, Guadalupe was even declared the co-patroness of New Spain along with St. Joseph, and Pope Benedict XIV granted a feast day and mass in her honor for December 12 in the year 1754.

This engraving shows the Virgin of Guadalupe coming to the aid of Mexico City during the 1736–37 epidemic. Importantly, the artist has shown criollos (kneeling in the foreground) as those explicitly receiving her protection. Frontispiece by Baltasar Troncoso y Sotomayor, in Cayetano de Cabrera y Quintero, Escudo de armas de México (Mexico City, 1746). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

She was so revered that people of different social and ethnic backgrounds paid her reverence. In particular, criollos (or creoles, pure-blooded Spaniards born in the Americas) promoted her devotional cult. They wrote some of the earliest texts recounting her miraculous appearance on Novohispanic soil, a fact they advertised as proof that God blessed the Americas and approved of a new nation. To support this notion, artists often included the motto “Non fecit taliter omni nationi” (Psalm 147:20—He has not dealt thus with any other nation) into their artworks.

Miguel González, The Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe), c. 1698, oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl (enconchado), canvas: 99.06 × 69.85 cm / frame: 124.46 × 95.25 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

True copies

Images depicting Guadalupe proliferated in the seventeenth century as devotion to her increased. Prints, paintings, and enconchados (oil painting and shell-inlay) replicate the original tilma image. Sometimes artists included inscriptions that mention the representation is a true copy of the tilma image.

Manuel de Arellano, Virgin of Guadalupe, 1691, oil on canvas, 181.45 x 123.38 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

For example, Manuel de Arellano writes “After the original” (Tocada el original) on his 1691 version of Guadalupe. This statement suggests that artists based their work on the original image and some of the power of the original image transferred to the replication. Besides replicating the tilma image, artists often included the narrative of the miracle in the four corners of the composition, as Arellano’s and Isidro Escamilla’s version from 1824 demonstrate. Frequently flowers frame the mandorla surrounding Guadalupe, a direct reference to the Castilian roses in Juan Diego’s tilma.

To prove further that New Spain was equal to Europe, some of the most famous artists of the eighteenth century, such as Miguel Cabrera and Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, were invited by the clergymen of the Basilica of Guadalupe to inspect the image on April 30, 1751 to authenticate that the image was indeed miraculous. In 1756, Cabrera published the result of this inspection as Maravilla Americana (American Marvel) in which he declared that the tilma image was indeed an acheiropoieta.

Guadalupe and national identity

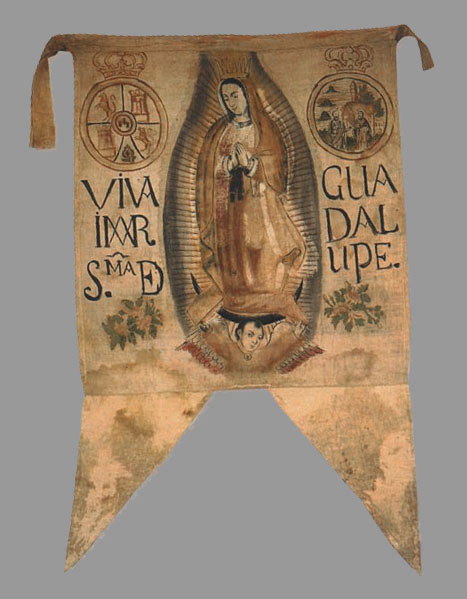

Standard of the Virgin of Guadalupe carried by Miguel Hidalgo during the start of Mexico’s War of Independence in 1810. (photo: Marcuse, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Other visual motifs further communicate the political connotations with which Guadalupe increasingly became linked. For instance, some artists placed an eagle perched on a cactus below Guadalupe (such as in the enconchado above), which had long functioned as a sign for the establishment of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan that became Mexico City after the Conquest. Guadalupe’s connection to creole identity and the creole desire for Mexican independence was solidified after father Miguel Hidalgo raised a liturgical banner of Guadalupe during his cry for independence in 1810.

Additional resources:

Read about Miguel González’s enconchado version on Smarthistory

Manuel de Arellano’s Virgin of Guadalupe at LACMA

Isidro Escamilla’s Virgin of Guadalupe in the Brooklyn Museum

Shrine of Guadalupe in the Catholic Encyclopedia

Director’s Journal: The Virgin of Guadalupe (video from the Indianapolis Museum of Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”guadalupe,”]

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:04] We’re in the Franz Meyer Museum in Mexico City, and we’re looking at an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe. This is a replica of the original miraculous image, which is in the Basilica of Guadalupe here in Mexico City.

Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:17] This particular image is not solely a painting. It’s actually what’s called “enconchado,” or mother-of-pearl shell inlaid, in this case into wood.

Dr. Harris: [0:27] That mother-of-pearl creates a reflective, iridescent surface that flickers and changes as your eyes move across it, that certainly suggests the heavenly and the divine.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:38] She’s shrouded in sunlight, she has stars on her cloak. This is imagery that comes from the Book of Revelation, talking about the Woman of the Apocalypse, who was similarly shrouded in the sun and had stars around her head, which have here been placed onto her cloak.

Dr. Harris: [0:55] And that she was standing on the moon, which we also see below her, supported by the figure of an angel. The Virgin of Guadalupe miraculously appeared to an Indigenous man named Juan Diego. This is only 10 years after Spain defeats the Aztecs.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:11] When she appears to Juan Diego on top of the Hill of Tepeyac, which you can still go to today, which is where the basilica is located, she speaks in his language, which was Nahuatl. She tells him to go to the bishop and to put a shrine in her honor at this hill.

Dr. Harris: [1:29] This is a moment in time when the Spanish are intensely converting the Indigenous peoples. This miraculous vision to an Indigenous person confirmed the correctness of replacing religions that were here with Christianity.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:47] In fact, the hill had been a location for an Earth Mother deity, where there had been a temple. After Juan Diego goes to the bishop, the bishop does not believe him. This happens several more times before the Virgin tells Juan Diego to gather up Castilian roses in his tilmar, his cloak, and to bring them to the bishop as a sign that she is actually appearing to Juan Diego.

[2:09] When he opens his tilmar, this cloak, before the bishop, not only do the roses fall out, but the miraculous image of Guadalupe is imprinted on it.

Dr. Harris: [2:19] That’s the image that’s in the Basilica of Guadalupe today.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:23] And we’re seeing the replica of here. She has this ashen skin, where she is known as the Dark Virgin, which has several layers of meaning. For one, it relates to the Old Testament “Song of Songs,” where the beloved says, “I am black but beautiful.” This woman in the Song of Songs is then read by Christians as an analog for the Virgin Mary.

Dr. Harris: [2:46] It’s also significant here in Mexico.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:50] Because there is the darker skin, she’s become this Indigenous avocation of the Virgin Mary.

Dr. Harris: [2:55] She’s so popular here in Mexico. She’s the patron saint of Mexico City. She was thought to have performed many, many miracles, even after the initial miracles with Juan Diego.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:07] She becomes the co-patroness of New Spain in 1737, after she intervenes in horrible epidemics that were killing lots of people. She really has become this major symbol, not only of Mexico but Mexican identity.

[3:21] I think what’s important here is this enconchado is helping to create an even more sacred image of Guadalupe.

[3:28] [music]