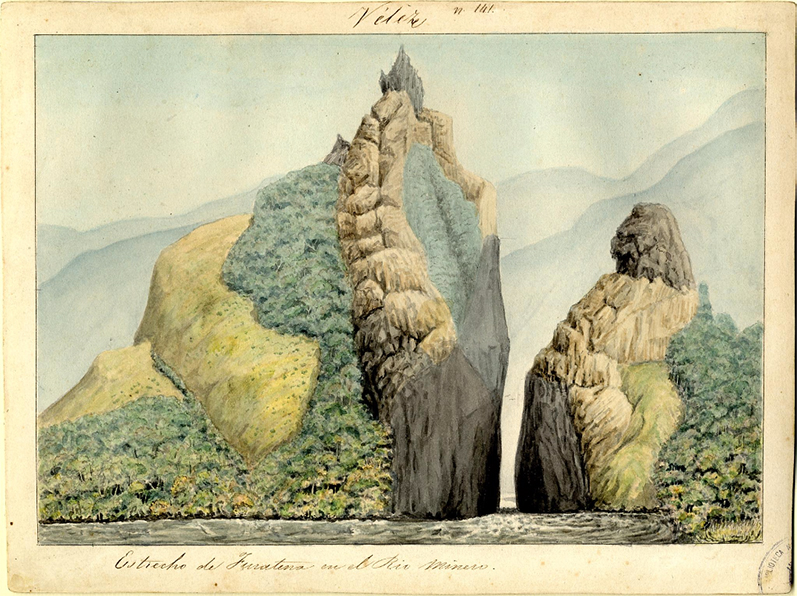

Carmelo Fernández, The Strait of Furatena in the Minero River, Province of Vélez, 1850-51, watercolor on paper (Colombian National Library)

Imagine floating down this river in a small rocking canoe that is being pulled by the current. How would you feel if you were about to pass through the narrow strait, not knowing if you would come out of the other end alive? Now, transport yourself to 1850, the moment when the Colombian government developed a project called the Colombian Chorographic Commission to survey the landscape of this newly formed nation (Colombia gained independence from Spain in 1819 under the leadership of Simón Bolívar, who died in 1830). The artists on the Commission portrayed natural features like this one through a Romantic lens that stemmed from European and North American traditions. These images in turn became important in the construction of Colombian national identity, even as the young nation was struggling with internal political stresses.

The Colombian Chorographic Commission

Scientists, writers, and artists were invited to join the Italian Colonel, geographer, and cartographer Agustin Codazzi, (who had previously worked on the Atlas of Venezuela in the 1830s) for this national geographic endeavor. The main goal of the project was to map the country, but it became much more than that. Nine years and three different artists later, the Chorographic Commission had produced both an Atlas of Colombia and many watercolor drawings that portrayed not only the physical landscape, but also social, economic, and agricultural aspects of the country, including its people, transportation, crops, and trades.

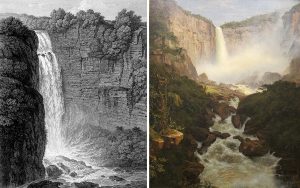

Two previous expeditions in Colombia had used art in the service of scientific documentation: the Botanical Expedition, directed by the Spanish doctor and botanist José Celestino Mutis, which lasted from 1763 to 1816; and Alexander von Humboldt’s voyage through Colombian territory in 1801. The North American landscape artist Frederic Edwin Church‘s stay in Colombia in 1853 also coincided with the first year of the Commission. Through these ventures, images became the means to portray new discoveries in the largely unexplored territory of Colombia. Mutis’s botanical drawings were a key part of the creation of a school of botanical studies. Humboldt, though not an artist himself, created drawings that were later made into prints that appealed to a public fascinated with travel, adventure, and the exotic, among them Church, whose painting Tequendama Falls near Bogotá echoes Humboldt’s drawing of the same place.

Left: Alexander von Humboldt, Tequendama Falls, 1810, lithograph, from Vues des cordillères (Paris: F. Schoell, 1810); right: Frederic Edwin Church, Tequendama Falls, near Bogotá, 1854, oil on canvas, 153.5 x 122 cm (Cincinnati Art Museum)

The Colombian Chorographic Commission was a state enterprise, originally developed and financed by the liberal governments of Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera and José Hilario López. The term “chorographic” comes from Ptolemy’s teachings, where “geographic” meant studying the entire world, and “chorographic” meant studying its smaller parts: basically, describing individual regions and their components. An 1839 law allowed the government of Colombia to hire engineers and geographers to chart the territory, but it took eleven years for this idea to be put into action due to political instability. A later law stated that a comprehensive description of the country, including its products and resources, should also be completed. Unfortunately, due to civil war, the Commission was cut short.

The Commission was composed of four parts: the mapping of the physical geography and the chorographic aspects of each province was led by Agustín Codazzi. There was also a literary aspect, entrusted to journalist Manuel Ancízar, who described the customs, people, and curiosities encountered by the expedition as entries in Bogotá’s Neogranadino newspaper (these were later edited into the book Pilgrimage of Alpha). The project’s graphic documentation was originally assigned to Carmelo Fernández, whose role was to create images of the landscapes, as well as images of people and genre scenes (this responsibility was later entrusted to Henry Price and then to Manuel María Paz). The botanical arm of the project was directed by Doctor José Geronimo Triana.

Carmelo Fernández, A Muleteer and a Weaver from Vélez, 1850-51, watercolor on paper (Colombian National Library)

Carmelo Fernández

Carmelo Fernández, the first painter in charge of the visual portion of the project, was born in Venezuela, the nephew of Venezuela’s President José Antonio Páez. A draftsman, painter, printer and engineer, Fernández was also in the army (where he met Simón Bolívar) and travelled extensively through Colombian territory during various independence military campaigns. He is best known for his portrait of Bolívar, which now decorates Colombian coins. Fernández arrived in Colombia in 1849 and signed a contract with the Commission in 1850. He is the author of the images that correspond to the Commission’s first and second expeditions, of which only 29 watercolors remain and which are now at the National Library Archives in Bogotá. These include landscapes, natural phenomena, places and objects of historical and archeological value, and images of people and customs (above). Fernández travelled to the northeastern region of the country known today as the territories of Boyacá, Santander, and Northern Santander.

Carmelo Fernández, Province of Vélez, The Strait of Furatena in the Minero River, 1850-51, watercolor on paper (Colombian National Library)

The Strait of Furatena in the Minero River

The Strait of Furatena in the Minero River exemplifies Fernández’s watercolors. The image is presented with a border around it because the drawings were usually turned into lithographic prints and the name of the province depicted was almost always printed on the top center of the border while a short title or description of the location was included at the bottom. Some illustrations of this type included measurements or other data that was recorded while on site.

The strait of Furatena was described by Manuel Ancízar in his book Pilgrimage of Alpha. He explained that to get there, the travelers of the Commission, including himself, Codazzi and Fernández, had to cut a path through the humid forest carrying pikes and machetes. He embellishes his description with measurements: for example, Fura (the peak shown on the left of Fernández’s image) measures approximately 2000 feet from the river to its top. He also includes observations such as the poor vegetation, except for some shrubs, on the mountain slopes.

Fernández endows his image with a certain sense of the romantic, showing the immensity and strangeness of the mountain cut by the narrow river that runs through it. The greater part of the mountain on the left (Fura), nearly touches the top of the frame with its peak, a detail that makes the landscape compositionally striking as it fills the frame. Tena, the smaller peak flanking the strait, occupies the tight space at the bottom right hand corner, next to the river, and then rises up to open the space towards the middle ground which has been carefully painted through subtle atmospheric perspective so as to show the more distant mountains behind, highlighting Colombia’s rocky terrain.

In addition to these topographical details, Fernández plays with tonal contrasts that guide the viewer’s eye both downward and up, from the dark passage between the strait to the illuminated peaks at top. By dramatizing the narrow passage in the foreground and the dramatic slope above, Fernández emphasizes the unusual and the monumental aspects of the Colombian landscape. A combination of scientific reportage and romantic vistas, the Colombian Chorographic Commission is a key event in mid-nineteenth century Colombian geography, politics, and art history.

Additional resources:

Frederic Edwin Church’s Tequendama Falls, near Bogota at the Cincinnati Art Museum

Carmelo Fernández’s A Muleteer and a Weaver from Velez at the World Digital Library