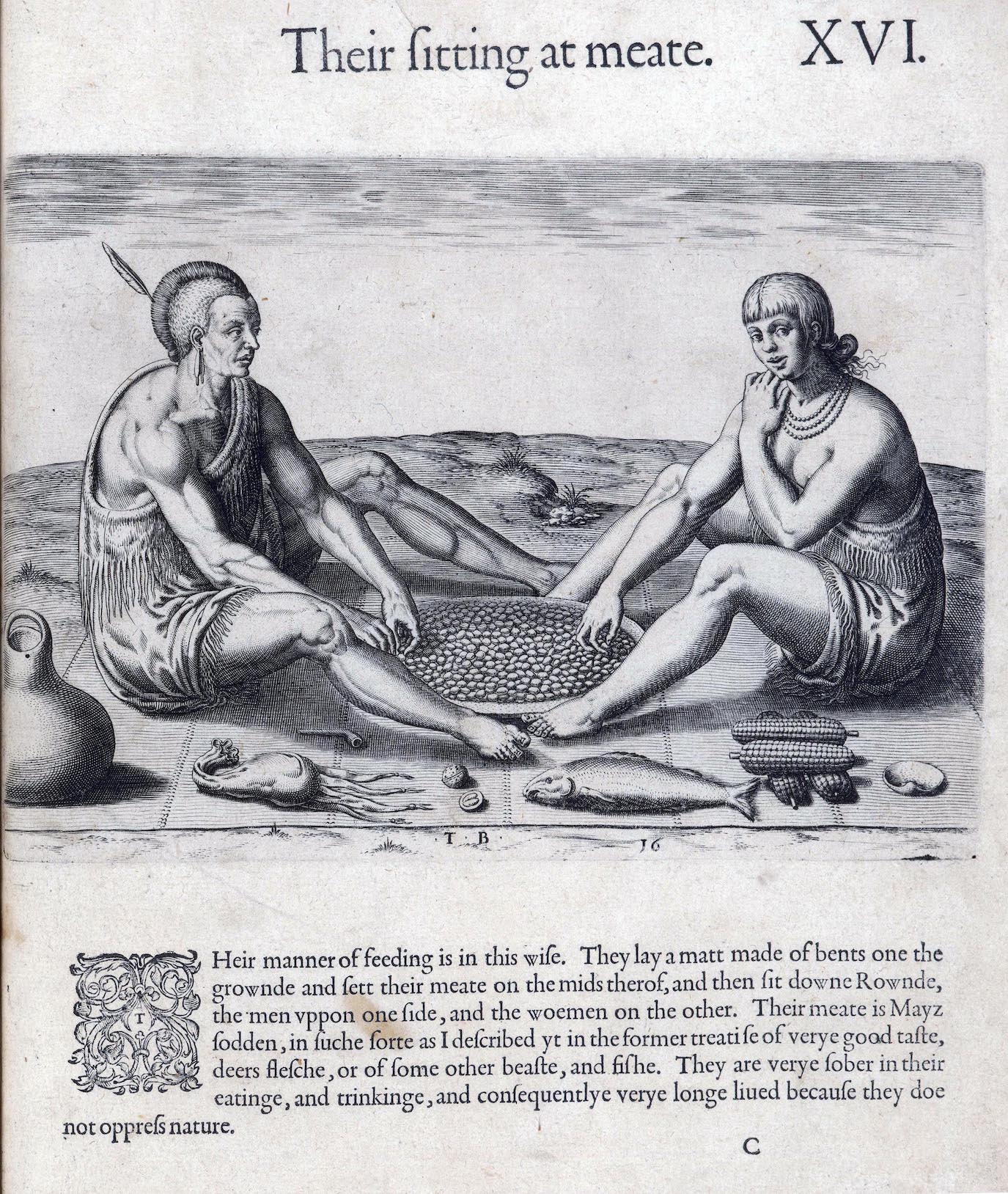

Inventing “America” for Europe: Theodore de Bry’s engravings of the Americas affirm and assert a sense of European superiority.

Read Now >Chapter 59

Art in American Colonies and the United States, c. 1600–1860

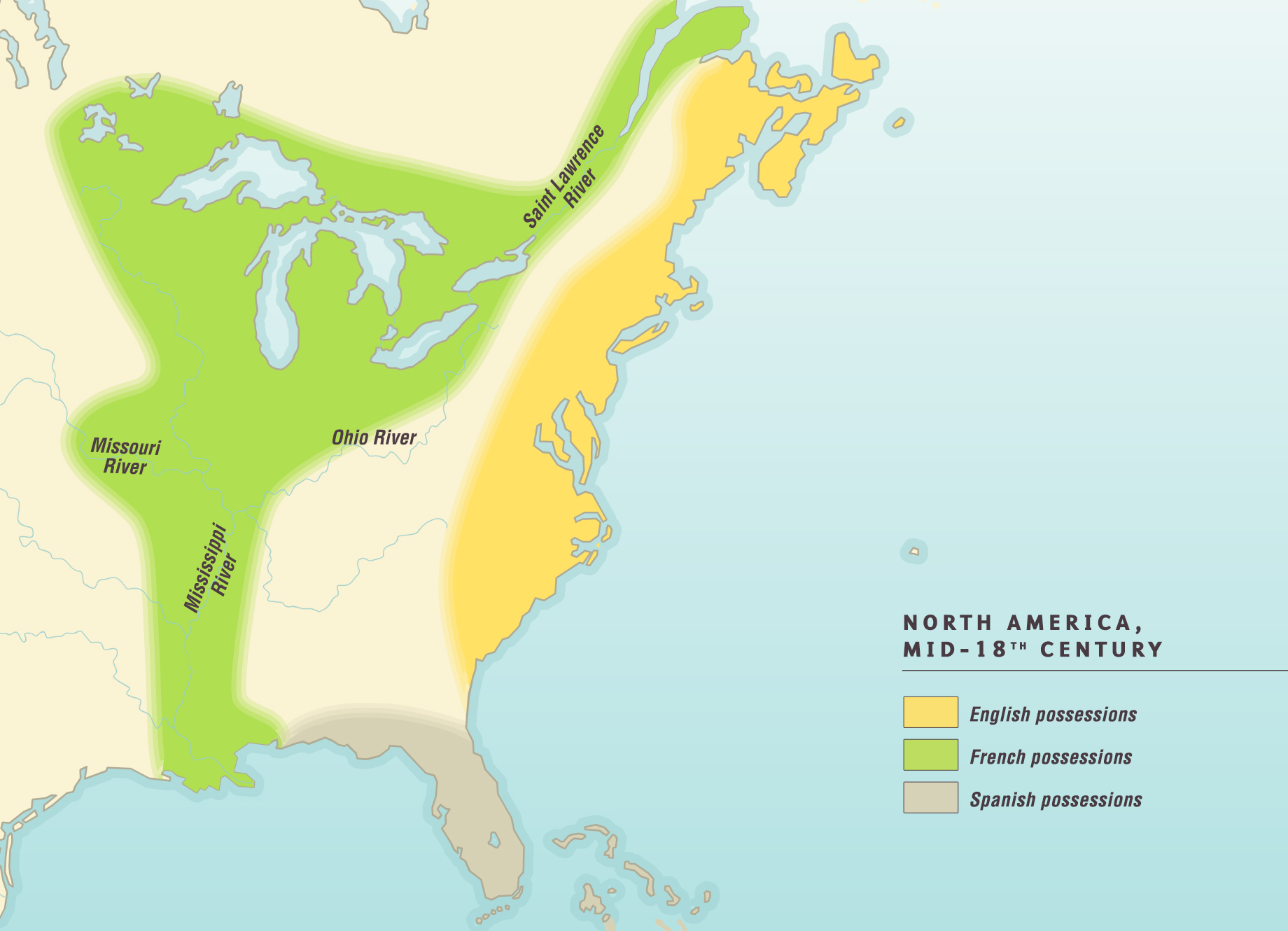

Map of part of North America in the mid-18th century showing English, French, and Spanish possessions (courtesy The Map as History)

Although this chapter covers only about 250 years (c. 1700–1865), the changes that took place on the continent of North America (and in this context, we will consider the parts of North America that are now Canada and the United States) during that time period were dramatic and far reaching. The European colonization of what is today the United States began in the sixteenth century when Spaniards founded Saint Augustine in Florida in 1565 and not long after colonized what is today New Mexico in 1598. The French colonization of Canada began in 1603, with the founding of New France on the coast of the Saint Lawrence River.

Theodor de Bry, Map showing the coast of Virginia with many islands just off the mainland, two Native territories, Secotan and Weapemeoc, and the Native community of Roanoak on an island at the mouth of a river, 1590, engraving based on the watercolor of John White, illustration in Wunderbarliche, doch warhafftige Erklärung, von der Gelegenheit vnd Sitten der Wilden in Virginia . . ., 1590, plate 2 (Library of Congress)

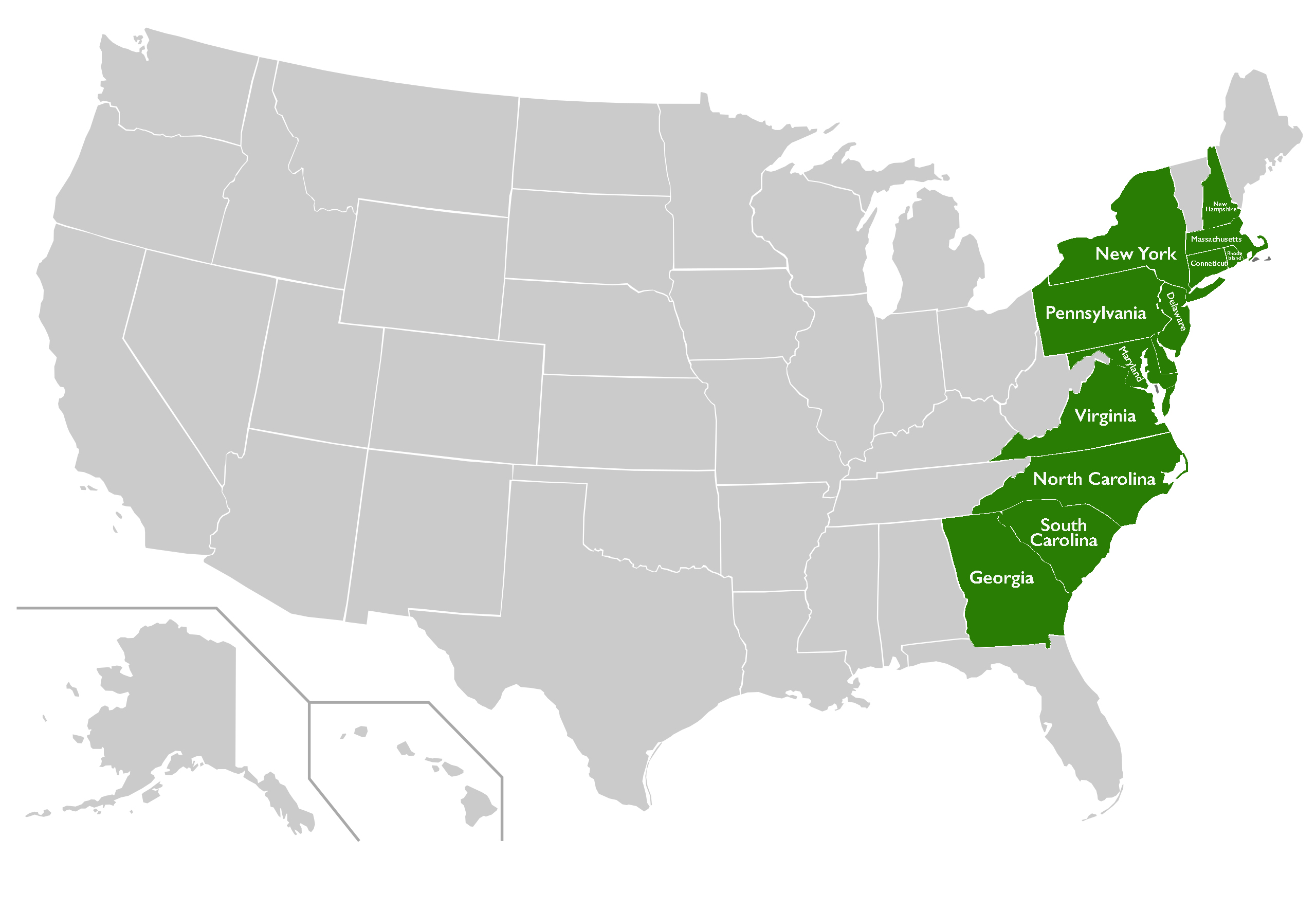

It was only in 1605 the the British founded Roanoke Colony in what would later be named North Carolina. Although Roanoke Colony failed while still in its infancy, two years later the British colony of Jamestown—founded in 1607—managed, despite starvation and disease, to survive. It is estimated that the combined European population of North America in 1610 was approximately 350. In contrast to this, a recent study has suggested that the population of Indigenous peoples in what is now the United States and Canada approached 7 million—a number that was greatly reduced in the decades following the arrival of Europeans due to genocide and the introduction of pathogens from Europe, Asia, and Africa to which the Indigenous peoples of the Americas had no protection.

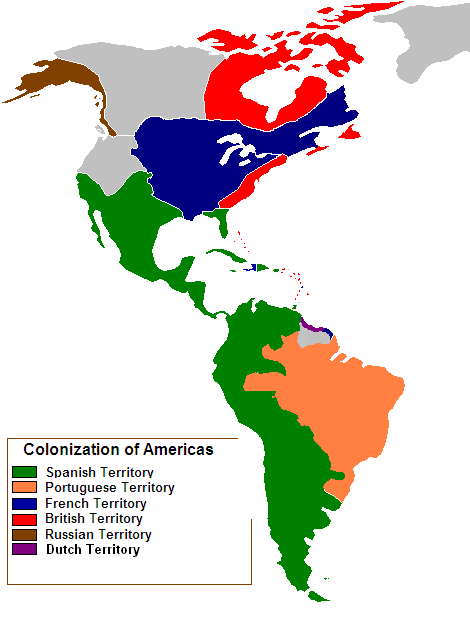

European-colonized lands in the Americas c. 1750

Yet big things can have small beginnings, and this is the case of the European settlement of the eastern seaboard of North America. By c. 1700, the population of these European colonies had swelled to more than 250,000 and extended from what is the Caribbean to Newfoundland. When speaking of the lands that would become the United States, historians have referred to this region as Colonial America, scholars now generally prefer to use the phrase American Colonies. Although this may at first seem to be a subtle—and some might suggest, an unneeded—differentiation, it is crucial. Whereas the phrase Colonial America suggests something that is singular, American Colonies reinforces the diversity of these groups of settlers. By the end of the seventeenth century, France, England, Holland, and Spain had all founded settlements in North America, and the reasons for the arrival of those colonists could be as varied as the point of their embarkation. Be it for religious liberty or for the dreams of prosperity and riches, the colonists were varied and diverse groups. Over this expanse of time, the art of North America likewise went through dramatic shifts and changes, and these changes also reflect the cultural fluidity in the colonies (and later, the United States), as well.

Map of the 13 American Colonies (map adapted from Connormah, CC BY-SA 3.0)

“American” and “America” are complicated words—they are typically used in relation to the United States of America, but there are many kinds of Americans and Americas, and people from the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central and South America consider themselves American, too. The earliest art made by settlers in what is now the United States and Canada during the end of the sixteenth century, shows the profound influence of European artistic precedents. This is not surprising, given that art was made by European artists for European audiences. But as the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries progressed, not only did the audience change, so too did the art makers, transitioning from artists born and trained in European to those who were born in the Americas.

Importantly, the subject of art likewise went through a shift. If the artists and architects in the decades prior to 1820 focused on portraiture, historical paintings, and classical inspired architecture, the art made during the later decades preceding the American Civil War focused on something uniquely American: the land.

In fact, the first centuries of “American” pivot around several key themes.

- The intent for artists to introduce a European audience to the recently discovered lands and people of the Americas.

- Colonial (and the slightly early Federal period) artists were strongly influenced by European precedents, both in style and genre.

- As the nineteenth century progressed, artists shifted their focus from portraits to landscapes, giving this genre a heightened pathos by combining landscapes with the moralizing messages of history paintings.

Early Beginnings and Colonial Maturation

It was only during the final decades of the sixteenth century that European-trained artists began arriving in bigger numbers in the Americas. The purpose of their arrival in North America was to depict the land, the people, and the customs of North American peoples, and—in no small part—to assert European superiority over them to an audience in Europe.

John White, “Their sitting at meate,” 1577–90, watercolor, 20.9 x 21.4 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

John White was born in London around the year 1540 and came to Roanoke Island in 1585 as an artist and mapmaker. The watercolors he completed during his stay in what is now North Carolina constitutes the oldest surviving visual record by a European artist of Native Americans in what is now the United States.

Theodor de Bry, “Their sitting at meate,” engraving, 15.2 x 21.2 cm (The John Carter Brown Library), after a watercolor of John White, 1577–90, from A brief and true report of the new found land of Virginia, 1590

These watercolors became the basis for a series of mass-produced prints by the Flemish printmaker, Theodre de Bry. As a result, White—through de Bry—was able to profoundly influence the European idea of what a Native American person looked like, where they lived, and what they ate. In doing so, de Bry was also contributing to a kind of homogenization of Indigenous cultures. During the sixteenth century, there were dozens of Indigenous groups living along the eastern seaboard, all with distinct cultures, dress, and traditions. But through the lens of European artists, these numerous groups were collapsed into a singular group of Native Americans.

Freake painter, Elizabeth Clarke Freake (Mrs. John Freake) and Baby Mary, c. 1671 and 1674, oil on canvas, 42 1/2 x 36 3/4″ / 108 x 93.3 cm (Worcester Art Museum)

If the end of the sixteenth century was a kind of birth of American art, then it was in the next 150 years or so that American art reached a kind of infancy. Artists of varying levels of skill, ability, and training arrived in the American colonies during the seventeenth century. Most of these painters—such as the anonymous painter who completed the portraits of the prosperous Puritan Freake family—were relatively untrained portraitists (limners, in the parlance of the day) who would have been a second- (or third-) rate artist in most hamlets in England.

Gerardus Duyckinck I (attributed), six portraits of the Levy-Franks family (Franks Children with Bird, Franks Children with Lamb, Jacob Franks, Moses Levy, Mrs. Jacob Franks (Abigaill Levy), and Ricka Franks), c. 1735, oil on canvas (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art)

Other artists—such as Gerardus Duyckinck—were born in the American colonies to artistically inclined families. It was not until 1729 with the arrival in Boston of John Smibert from London when North America had its first supremely talented European-trained painter. Smibert not only painted portraits of the Boston elite, he also opened what was in essence the first art gallery in the Americans and displayed his own copies of European paintings.

Watch videos and read essays about early beginnings and colonial maturation

Portraits of John and Elizabeth Freake (and their baby): These pendant portraits eloquently speak as to what it meant to be part of the upper-middle-class elite in Colonial New England during the final decades of the seventeenth century.

Read Now >

Gerardus Duyckinck I (attributed), Six portraits of the Levy-Franks family: A Jewish family in early New York.

Read Now >

John Smibert, The Bermuda Group: Although this image was never intended to remain in Boston, it stayed in the artist’s Boston studio and served as the cornerstone for what many consider to be that city’s first museum.

Read Now >/4 Completed

John Smibert, The Bermuda Group, 1728, reworked 1739, oil on canvas, 69 1/2 x 93″ / 176.5 x 236.2 cm (Yale University Art Gallery)

Maturations of the 18th century

Some of the greatest colonial-born artists who followed Smibert—Robert Feke, John Singleton Copley, John Trumbull, and Gilbert Stuart among others—acquired some of their earliest art education by seeing the paintings in Smibert’s art gallery.

John Singleton Copley, Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Mifflin (Sarah Morris), 1773, oil on ticking, 156.5 × 121.9 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Some eighteenth-century portraits painted in the colonies—from those of the Freake family to those Copley painted such as the dual portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Mifflin—all speak to a kind of dialogue between European artistic precedents and the interests of a North American audience.

Covered sugar bowl, c. 1745, silver, 11.5 x 9.1 cm (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

But it is not just in painted portraits in which this conversation happens, for that same silent transcultural discussion happens between more everyday kinds of objects. For example, a silver bowl is not just a silver bowl. It is an object that speaks to wealth, power, and servitude when we consider the value of the materials, the privilege of its sweet contents, and the fact that the forced labor that created the sugar would never enjoy it.

Anishinaabe outfit, c. 1790, collected by Lieutenant Andrew Foster, Fort Michilimackinac (British), Michigan, Birchbark, cotton, linen, wool, feathers, silk, silver brooches, porcupine quills, horsehair, hide, sinew; the moccasins were likely made by the Huron–Wendat people (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution)

Likewise, an extravagant Anishinaabe military uniform made for Lieutenant Andrew Foster’s is about more than commerce and exchange, it is also about diplomacy and cooperation. The cotton of the uniform was exported from India and then later milled in Britain. The extravagant decoration on the cotton garment contains Italian glass beads and Native American embellishments.

While the cotton in Andrew Foster’s uniform was grown in India, cotton became one of the most important crops in the American colonies and later in the United States. Cotton is a laborious crop to harvest, and the lucrative nature of cotton was made possible through the utilization of slave labor. There is a misperception that slavery existed only in the southern colonies and states, places such as Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama. In fact, in 1817 New York became the first state to formally outlaw slavery, setting 4 July 1827 as the date of total emancipation of all enslaved peoples.

Rodney Leon, African Burial Ground National Monument, 2006, New York City

To put this in perspective, the Dutch founded New York—then New Amsterdam—in 1624, and the first enslaved peoples arrived in 1626, only two years later. This means that New York City has a longer history of being a slaveholding city (as of 2022, 203 years) than it does of being a city of emancipation (195 years). To acknowledge this fact, Rodney Leon designed the African Burial Ground in lower Manhattan. Using an Old Kingdom Egypt burial structure and West African iconography, the memorial brings important attention to the presence of slavery in the north while remembering the thousands who lived in bondage there.

Watch more videos and read more essays about colonial maturation

John Singleton Copley, Portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Mifflin (Sarah Morris): On the eve of the American Revolution, a glimpse of politics in portraiture.

Read Now >

A covered sugar bowl: The triangle trade and the colonial table, sugar, tea, and slavery.

Read Now >

/4 Completed

Neoclassical Influences and the Construction of National Identity

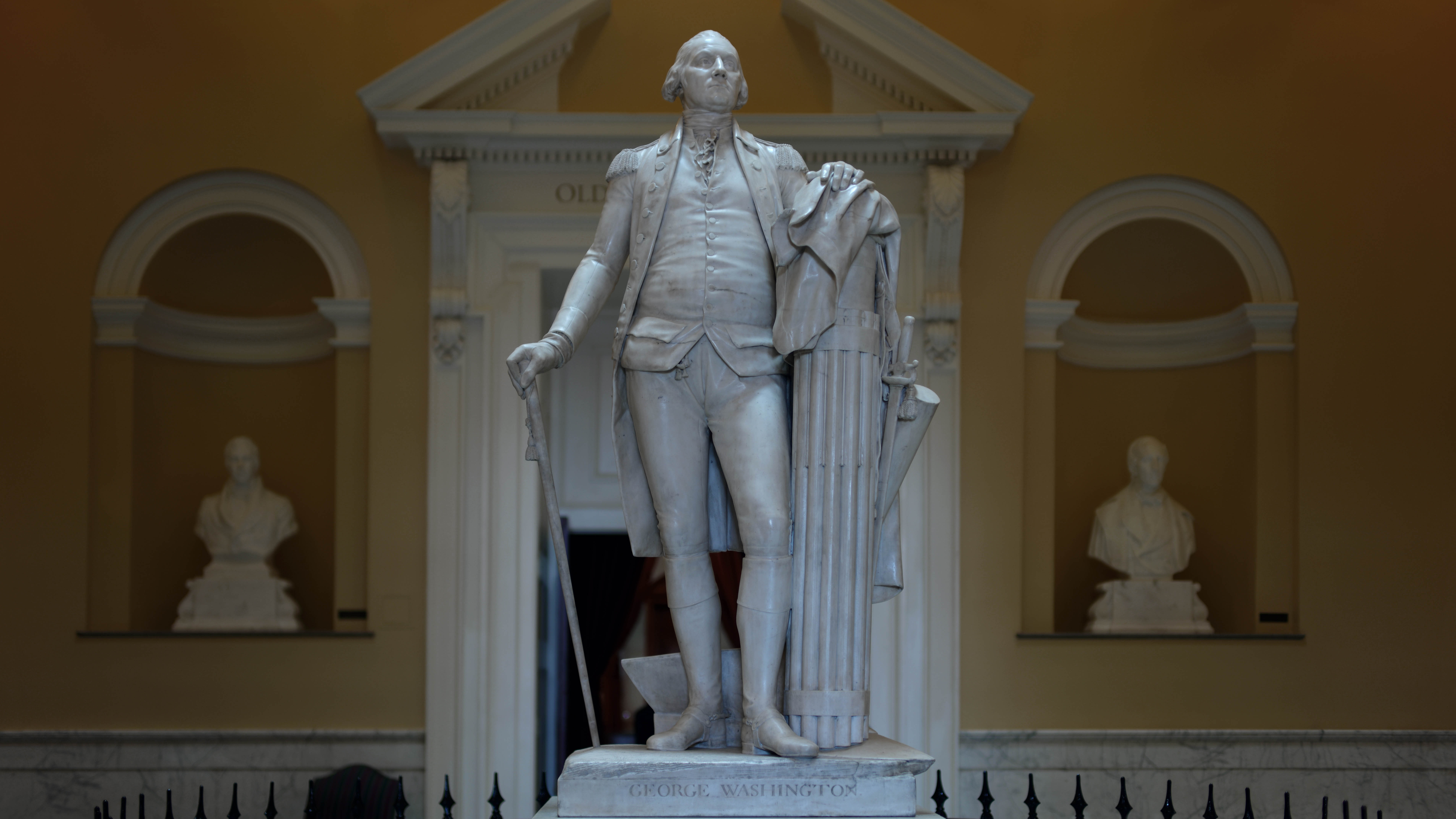

Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington, 1788–92, marble, 6′ 2″ high (State Capitol, Richmond, Virginia)

The Battle of Yorktown on 19 October 1781 brought the fighting of the American War of Independence to an end, and with the Treaty of Paris—signed on 3 September 1783—Great Britain formally acknowledged the United States as a sovereign nation. In the years that followed, American artists—and the federal and state governments—sought ways to both commemorate this victory and to construct a national identity in art and architecture. Jean-Antoine Houdon—a French neoclassical sculptor—carved a monumental statue of George Washington in his military uniform.

John Trumbull, The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, 17 June, 1775, after 1815-before 1831, oil on canvas, 50.16 x 75.56 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

And the painter we most identify with this goal during the early Federal period is the former Revolutionary War officer John Trumbull who is most well-known today for his large-scale history paintings that chronicled this conflict with Great Britain.

Thomas Jefferson, Rotunda, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1819–26

One of the architects we most identify with the early Federal period developed his architectural aesthetic while living in France. His name was Thomas Jefferson, and in addition to designing his ancestral home and the Rotunda at the University of Virginia—the university he himself founded—he also had a small side hustle in politics, eventually serving as the third president of the United States.

Primary source excerpt

From 1809 to 1819, when Thomas Jefferson was developing his vision for a new form of public higher education in Virginia, he and the other men he worked with to bring the vision to reality did so in the single largest slaveholding state in the United States. All of the men involved were large slaveholders. Thomas Jefferson owned 607 people over the course of his life.

Slavery and the University, The University of Virginia (2018), p. 15

Jefferson’s architectural vision is classified as neoclassical, a style that was developed in France in the period leading up to the French Revolution, when the French people attempted to place restrictions on the power of their king. It is a style that looks back to ancient Greek and Roman architecture and is meant to signal ideals of freedom and liberty. For many years art history largely ignored the irony of Jefferson’s ideals and his reality as an enslaver. We can also consider the fact that an enslaved person named Lewis Commodore was purchased and owned by the University of Virginia directly (others who worked there were rented or borrowed), and worked to clean the rooms of the beautiful Rotunda that Jefferson designed (and he even lived there for a period).

Portraiture and history painting in the 18th century

The dominant form of art during the eighteenth century was portraiture. Indeed, if an affluent patron wanted to pay for a work of art, they generally wanted a likeness of themselves or a member of their family. But in the closing triad of this century, artists born in the American colonies began to seek out artistic instruction in Europe, and in doing so were introduced to European art first-hand.

When they arrived in Europe, American artists learned that the various art academies throughout Europe—the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture in France amongst others—had established an unofficial hierarchy of the subjects of art. This hierarchy suggested that the most skilled, able, and intellectually engaged artists worked in the realm of large-scale “Grand Manner” history paintings (subjects from history, mythology, or the Bible). In picking such a topic, the artist was often allowed the opportunity to visually depict a written source and this provided artists the chance to engage their intellect in the purpose of providing moral or intellectual instruction to the viewer.

If history paintings were at the apex of this hierarchy, portraiture and genre paintings (small compositions depicting everyday life) were near the bottom. In both instances, artists were again allowed the opportunity to compositionally arrange a painting, but without—perhaps—the opportunity to morally instruct the viewer. The genre of landscapes was also at the lower end of the hierarchy since it was deemed less prestigious since it was understood as only a mechanical recreation of what the Great Artist—God—had already made.

John Vanderlyn, Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos, 1809–14, oil on canvas, 174 x 221 cm (The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)

Many artists who had journeyed to Europe returned to the United States with goals of creating large scale Grand Manner history paintings in the vein of the French painter Jacques-Louis David. For some—such as John Trumbull—this meant completing works that celebrated the colonial victory over Great Britain. For John Vanderlyn, the first American-born artist to enroll at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, this meant large-scale history paintings that often depicted stories from the classical (Greco-Roman) past.

Thomas Jefferson and Charles-Louis Clérisseau, Virginia State Capitol, completed 1792

But Vanderlyn was not the only American artist to be inspired by the French neoclassicism en vogue in Paris during the decades around the turn of the nineteenth century. So too was Thomas Jefferson, who, although never formally trained as an architect, brought a keen understanding of the ways in which architecture could forge a national identity. He chose classical (ancient Greek and Roman) precedents for the buildings he designed—the Rotunda at the University of Virginia harkens back to the Pantheon in Rome, and his Virginia State Capitol is similar to the Maison Carrée in Nîmes.

Born and trained in Ireland, architect James Hoban emigrated to Philadelphia in 1785 and won the design competition for the White House in 1792. It has housed every American president except George Washington. James Hoban, The White House (photo: Cezary Piwowarczyk, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The same connection can be made in regards to James Hoban’s White House and Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s Capitol Building—both of which have strong classical precedents. In making this connection between the United States and the classical world, Jefferson (and others!) aspired to connect what they saw as the longevity and benevolence of the classical governments with what they were building in the United States.

Read essays and watch videos about neoclassical influences and the construction of national identity

John Trumbull, The Declaration of Independence: Trumbull traveled up and down the Eastern Seaboard to paint the members of the Continental Congress from life.

Read Now >

John Vanderlyn, Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos: Unusually early for an American artist, Vanderlyn trained in France.

Read Now >

Jean-Antoine Houdon, George Washington: Lack of an American sculptural tradition compelled Jefferson to look to France for this portrait of Washington.

Read Now >

Thomas Jefferson, Monticello: Jefferson was a supporter and practitioner of classical architecture.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Shift towards Romanticism, the land, and a new National Identity

Washington Allston, Elijah in the Desert, 1818, oil on canvas, 125.09 x 184.78 cm / 49 1/4 x 72 3/4 inches (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Europe had history and portrait paintings during the eighteenth century. But there were some things Europe simply did not have during this period, and one of those things was, at least from a non-Indigenous perspective, the untamed and expansive landscape of North America. And it is through this lens—that there is something here that is different (even better!) than over there—that American art of the nineteenth century can be considered. During the early nineteenth century, artists—be they born in America or imported from abroad—began to shift their focus away from the subjects that had hitherto been deemed appropriate (portraits, history paintings) towards others that had been largely ignored. One such genre was that of the landscape.

Thomas Moran, The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1872, oil on canvas mounted on aluminum, 213 x 266.3 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Lent by the Department of the Interior Museum)

With the rising influence of Romanticism towards the end of the eighteenth and into the first quarter of the nineteenth century, the prominence of the European hierarchy of subjects (which placed history paintings at the apex) began to steadily decrease. Nowhere was this truer than in the United States, a place where portraiture had reigned supreme since colonial times. But beginning in the nineteenth century, landscapes became increasingly more popular, for America—more populated along the seaboard—was imagined as a New Eden, a kind of uncivilized wilderness, inhabited by only Indigenous cultures who, so the thinking went, could be easily displaced—and likewise disregarded the populations of areas once controlled by the Spanish Crown and which were now independent or formed part of independent Mexico. As such, American landscape artists felt they had something unique to contribute to the art world. But it was not just the land that was new; artists began to incorporate historical or allegorical elements into their landscapes, creating works of art that had both a depiction of the land and a morally instructive message.

Thomas Cole, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow, 1836, oil on canvas, 130.8 x 193 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Thomas Cole’s 1836 masterpiece The Oxbow is but one clear example. At first view, this painting might seem to be only a composition that visually chronicles a lovely bend in the Connecticut River near Northampton, Massachusetts. But on more thorough examination, this painting has interesting and insightful things to say about a variety of historical and political happenings that were occurring in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century. This painting is not only about the land, it speaks to the idea of Manifest Destiny (the political ideology that justified westward expansion and thus the violence against Native Americans and their removal from their lands). Thus, what Cole—and many other artists—managed to do was to create a kind of historical landscape painting, a composition that did the intellectual work of history painting but used the (American) landscape to fulfill those cerebral ends.

Catlin painted this portrait of The White Cloud around 1844, twenty years after the Iowa tribes were forced by the U.S. government to move from Iowa to small reservations in Kansas and Nebraska. The displacement from their ancestral and spiritual homeland left the dwindling Iowa people in a fragile state. George Catlin, The White Cloud, Head Chief of the Iowas, 1844–45, oil on canvas, 71 x 58 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Although the phrase Manifest Destiny was first coined in 1845, it only put into words an idea that had very much been a part of the ideology of the United States during the entirely of the nineteenth century: that the entire continent was available to those of European descent who inhabited the eastern seaboard, and that it was almost a divine mandate to move westward to occupy the continent. But Manifest Destiny is a complicated historical theme, and this westward expansion caused the forced displacement of numerous Indigenous peoples, and in many instances, exposed these groups to white explorers and settlers who introduced deadly pathogens to which Native populations had no immunity. These epidemics had disastrous effects upon Native groups, reducing hitherto immense populations to the brink of extinction.

Quilled war shirt (front), c. 1800–20, Native tanned hide, porcupine quills, red trade cloth, dyes, and sinew, 34 x 43 inches (Denver Art Museum)

For example, two smallpox epidemics reduced the Great Plains Mandan Nation from a population of 15,000 to less than 200 in the span of 56 years. What Manifest Destiny helped achieve for the Mandan Nation was tragic death, terrible sorrow, and a more than 98% reduction in population—and resulted in the near elimination of Mandan visual culture. The Quilted War Shirt in the Denver Art Museum is important not only for the important narrative it suggests in its decoration, but by its very production (and survival).

Watch videos and read essays about Romanticism, the land, and a new National Identity

Washington Allston, Elijah in the Desert: Allston is considered America’s first Romantic painter.

Read Now >

Thomas Cole, The Oxbow: Not content to merely paint the land, Cole elevated the landscape to approach the status of historical painting.

Read Now >

Imagining the West, territorial expansion, and the politics of slavery: Americans’ stance on slavery colored their visions of the West.

Read Now >

Albert Bierstadt, Hetch Hetchy Valley, California: Captured here in paint, this grand Californian landscape would soon disappear under water.

Read Now >

George Catlin, The White Cloud, Head Chief of the Iowas: This dignified portrait of a Native leader belies the cruel treatment he endured at the time of its painting.

Read Now >

War Shirt (Upper Missouri River): A rare early Plains war shirt and cultural resilience in the face of disease.

Read Now >/6 Completed

The American colonies—and later the United States—were constantly changing during the centuries prior to the U.S. Civil War, and this dynamism can be seen in the artistic record. Some of the earliest efforts attempted to visually chronicle Native Americans. Successive generations of artists built upon European artistic precedents for a colonial (and later, a United States) audience. As the nineteenth century progressed, artists such as Thomas Cole focused their artistic energies on the American landscape, creating allegorical works that frequently commented on westward expansion of the continent, a process that had disastrous repercussions to the Native Americans who already occupied these lands.

Martin Johnson Heade, Approaching Thunder Storm, 1859, will on canvas, 71.1 x 111.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Landscape paintings could serve many purposes. Many artists (along with just about everyone else) saw the U.S. Civil War looming on the horizon and responded, though in ways that may not always be apparent to us in the 21st century. Art historian Eleanor Harvey has described how landscape paintings were put to use by artists to express the national frame of mind during this period. For example, Martin Johnson Heade’s 1859 painting Approaching Thunderstorm, which might look like a straightforward landscape painting of a man and his dog sitting at the edge of a bay with a storm in the distance, referred to the looming crisis over slavery that would lead to the U.S. Civil War. Harvey points out that those who advocated for the abolition of slavery used the idea of a coming storm that would not be stopped by human agency to describe the impending war.

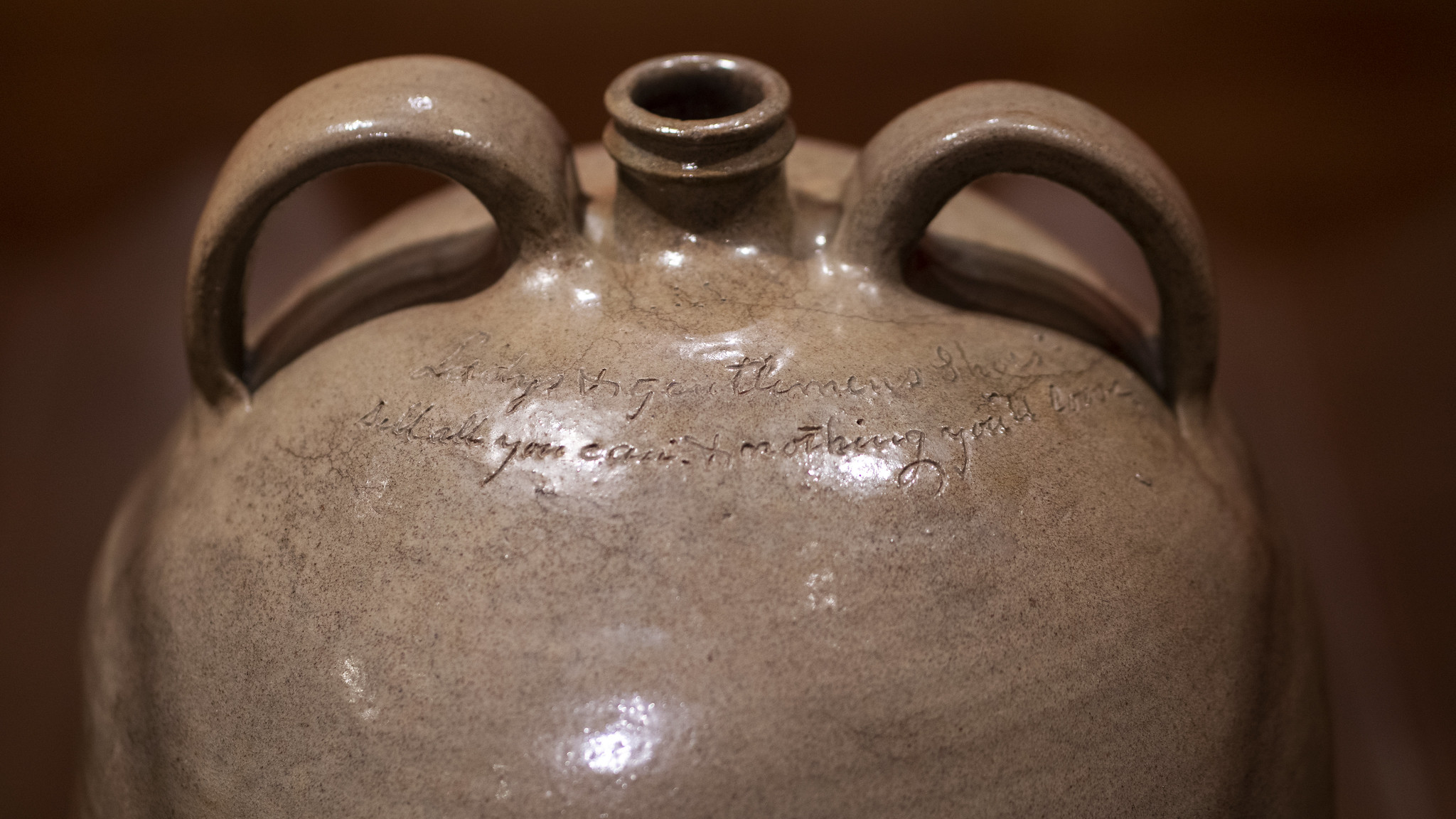

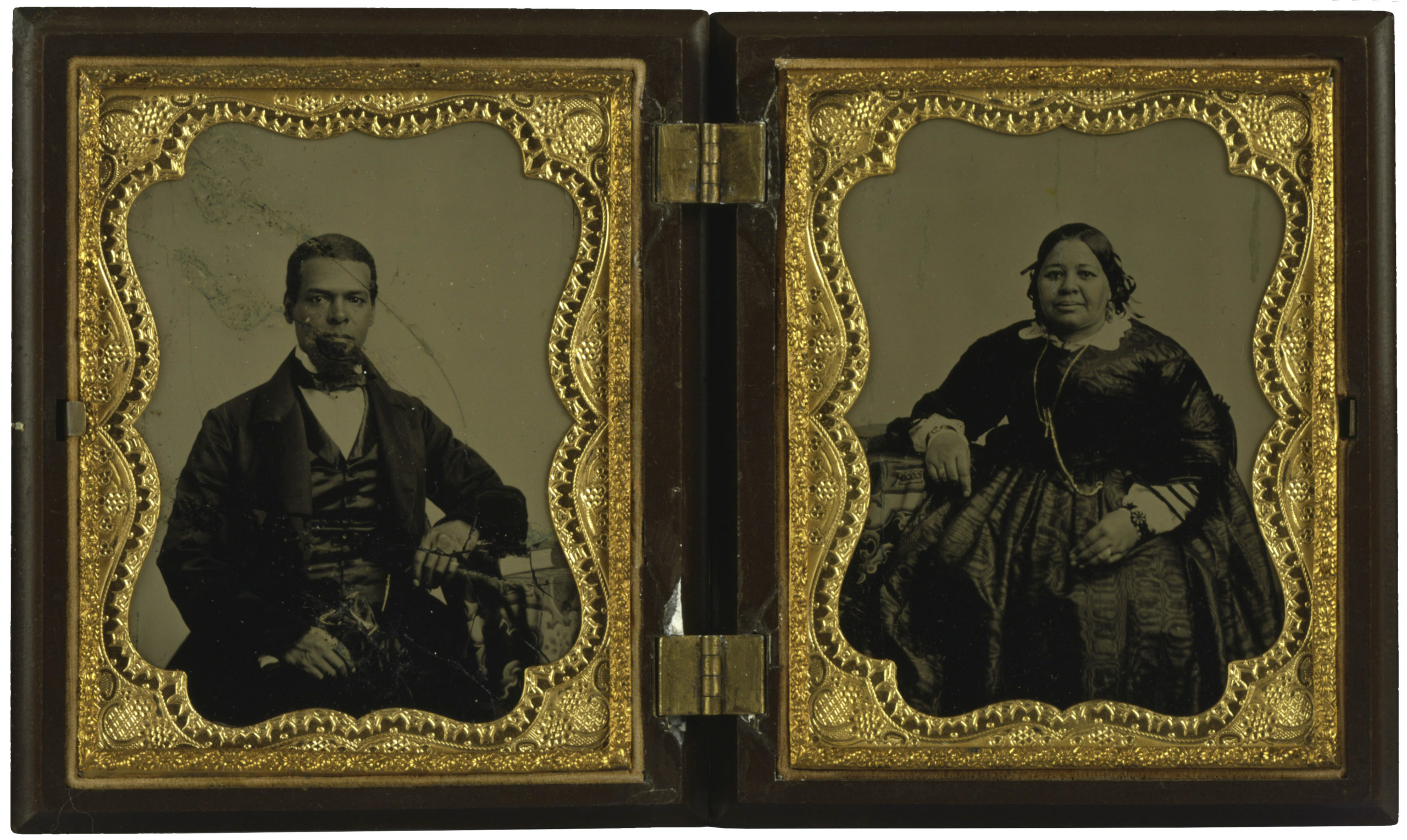

It is important to remember too that the artists who created images responding to the events leading up to the war were white and mostly lived in the northern United States. Not surprisingly, few, if any, images survive that were made or commissioned by enslaved people that address their lived experience. We are fortunate to have the beautiful pottery made by an enslaved man named David Drake. Even more remarkable, Drake signed and often inscribed his pots at a time when literacy among the enslaved (and often the broader Black population) was illegal.

Learn more about the art that was made just before the U.S. Civil War

The problem of Picturing Slavery: Not surprisingly, few, if any, images made or commissioned by enslaved people that address their lived experience survive.

Read Now >

David Drake, Double-handled jug: Enslaved artist David Drake inscribed a poem onto this jug at a time when literacy among enslaved people was outlawed.

Read Now >

Seneca Village: The creation of a beloved landmark in New York City destroyed a thriving community of African Americans and Irish immigrants.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Key questions to guide your reading

How did artists introduce European audiences to the recently colonized people and land of the Americas?

What European precedents influenced colonial and early Federal period artists?

Why did artists shift their focus to creating landscape paintings over the course of the 19th century?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did artists introduce European audiences to the recently colonized people and land of the Americas?

What European precedents influenced colonial and early Federal period artists?

Why did artists shift their focus to creating landscape paintings over the course of the 19th century?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

America, American

American Colonies

Classical

Federal period

History painting

Landscape painting

Manifest Destiny

Neoclassical

Romanticism