John Vanderlyn, Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos, 1809–14, oil on canvas, 174 x 221 cm (The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Unusual training for an American

John Vanderlyn is different from most of his American-art peers.

For more than forty years, nearly every American who aspired to be an artist sailed eastward across the Atlantic Ocean to study in the London studio of the Pennsylvania-born painter Benjamin West. Indeed, the artists whom West either taught or professionally advised comprises a ‘who’s who’ of colonial and early Federal art, and include famous names such as John Singleton Copley, Charles Willson Peale, Gilbert Stuart, John Trumbull, and Thomas Sully. The reason for this need for transatlantic travel was simple; whereas London had the Royal Academy of Art and Paris had the École des Beaux-Arts, North America had little other than a few undistinguished art academies and even fewer public collections of art. Aspiring artists had to go where the art and artists were. For those from North America, that had meant London.

But Vanderlyn did not go to London to search out West’s advice or instruction. While a teenager, Vanderlyn moved from his home in Kingston, New York to New York City, and then later studied with Gilbert Stuart, the portraitist, who had recently returned to American shores after 18 years in London and Dublin. Stuart provided art lessons and allowed his pupil to copy portraits.

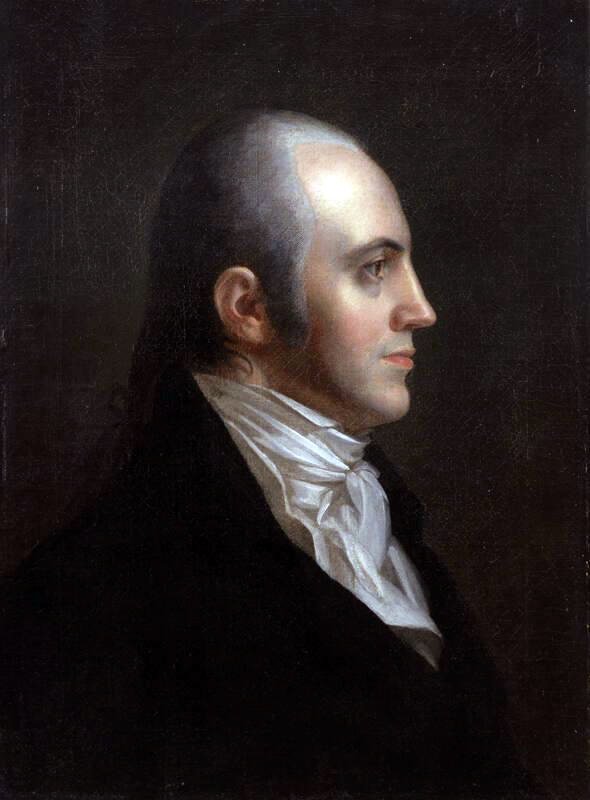

John Vanderlyn, Aaron Burr, 1802, oil on canvas, 56.5 x 41.9 cm (New York Historical Society)

One such image Vanderlyn copied was Stuart’s portrait of Aaron Burr, New York’s Democratic-Republican senator (and later vice president under Thomas Jefferson). This brought the younger artist to the attention of the ambitious politician, and Vanderlyn became a kind of protégé to Burr, living for a spell of time in his residence just outside New York City, Richmond Hill. There can be no doubt that Stuart would have encouraged Vanderlyn to study with his former teacher, Benjamin West. When considering Burr’s strong anti-English and Francophile sentiments, however, Burr instead paid for Vanderlyn to study and train in Paris, thus breaking West’s near monopoly in the instruction of American artists.

François-André Vincent, Germanicus Calms Sedition in his Camp, 1768, oil on canvas, 119.5 x 145 cm (Beaux-Arts de Paris, France)

Paris and Neoclassicism

When in Paris, Vanderlyn was the first American to study at the Académie de Peinture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and studied with François-André Vincent, a winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome and somewhat of an artistic rival to the more famous Jacques-Louis David. In doing so and over time, Vanderlyn fully embraced and absorbed the Neoclassical style that was then flourishing on the continent.

No painting better demonstrates Vanderlyn’s commitment to French Neolassicism in regards to form and content better than his masterwork Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos.

John Vanderlyn, Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos, 1809–14, oil on canvas, 174 x 221 cm (The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Ariadne abandoned

Painted in Paris and shown at the 1812 annual Salon (the name of the official exhibitions), Vanderlyn depicts a narrative from the classical past. Princess Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos of Crete, assisted Theseus in slaying the Minotaur that lived under the palace. As a reward for his victory, Ariadne and Theseus eloped and sailed for Athens, Theseus’s home. After a sexual encounter on the island of Naxos, Theseus abandoned his new bride. Lest we feel sorry for her, she is later rescued by Dionysus who marries her and places her crown in the heavens as the constellation Corona Borealis.

The moment Vanderlyn depicted in his monumental canvas was the point when Theseus was reaching his boat to make his getaway. Ariadne, nude, and in what appears to be a post-coital slumber, lies upon a red drapery, her arms raised to her head. In a painting largely filled with muted earth tones, this red blanket gathers the visual attention of the viewer. A white sheet wraps around upper thigh. It both conceals and at the same time brings attention to her nudity. Her body—which Vanderlyn has painted a pale milky-white value—contrasts with the North American-like landscape in which she reclines. In the right middle ground one can see the minutely painted boat Theseus boards in order to abandon Ariadne.

Neoclassicism

Certainly, this image depicts a narrative taken from the classical past, and as such, it fits well under the broad umbrella of Neoclassicism in regards to subject. However, it is also Neoclassical in form when compared to the romantic works painted at about the same time.

Francisco Goya, The Third of May, 1808 in Madrid, 1814–15, oil on canvas, 268 x 347 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

Indeed, one need only compare Ariadne with, for example, Goya’s The Third of May, 1808, painted just two years later, to appreciate the differences between these two different styles. Whereas Vanderlyn’s composition is linear, concise, and has a somewhat muted palette, Goya’s painting is painterly, loosely composed, with an energetic use of color.

Vanderlyn’s composition was favorably received when he exhibited it in Paris. This can be partially explained by the still popular Neoclassical style and the ways in which it referenced back to the great reclining nudes of the Renaissance—Titian’s famous Venus of Urbino is but one example. Moreover, Vanderlyn’s painting also anticipates many famous examples that would come later in the nineteenth century.

Alexandre Cabanel, Birth of Venus, 1863, oil on canvas, 130 x 225 cm (Musée d’Orsay, Paris)

Indeed, one can see echoes of Vanderlyn’s Ariadne in many paintings to follow. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Grande Odalisque, Édouard Manet’s Olympia, and Alexandre Cabanel’s Birth of Venus are but three well-known examples. Clearly, Europe had an appetite for paintings of the reclining female nude.

An unpopular image at home

But the audience in Europe was very different from the one Vanderlyn found when he returned to New York to exhibit Ariadne in the United States. Although he had found encouragement in Paris, the more puritanical mindset of his home country combined with the lack of tradition of the female nude in American art made this an unpopular image. Vanderlyn had hoped to return to the United States and paint large-scale Neoclassical history paintings. Instead, he placed his Neoclassical efforts into portrait painting, a genre he had hoped to avoid (in the hierarchy of subject matter determined by the academies, portrait painting ranked lower than history paintings). He died at the age of 76 in near poverty. It was not until after his death that his French training or his Neoclassical style were recognized as being key contributions to the very beginnings of art in the United States.