Quilled war shirt (front), c. 1800–1820. Native tanned hide, porcupine and possibly bird quills, plant material, red trade cloth, dyes, and sinew. 34 x 43 inches (Denver Art Museum)

Studying art during a pandemic

As many of us find ourselves working and studying from home while social distancing during the world-wide spread of COVID-19, let us think about the impact other pandemics and epidemics have had on world populations and their arts. Visual records open a window into such events, as we see in depictions of leprosy in European medieval illuminated manuscripts or in pictographic accounts of smallpox epidemics that spread across the Great Plains of North America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[1] Northern plains groups experienced 36 epidemics between 1714 and 1919, which were documented in chronological order in winter counts.[2] A winter count depicted the most important events that occurred in any given year. Community elders would meet each year to discuss what had occurred since winter started (denoted by the first snowfall), and would select the most important event to name the year, after which a symbol (or pictograph) would be created and added to a hide painting.

One example is the 1837–38 smallpox epidemic which was catastrophic for the Mandan Nation.[3] According to historian Clay Jenkinson “In two waves of smallpox on the Upper Missouri, separated by 56 years, the Mandan had been reduced from a proud nation of more than 15,000 individuals to a pathetic remnant of 145.”[4] With so much loss we must consider the dramatic impact such events had on the transmission of Indigenous knowledge, but also celebrate these communities’ perseverance, and ability to adapt. Today the population of the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara) have again risen to around 15,000 citizens who live on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota.[5]

Understanding this history of pandemic and loss provides us with a lens through which to see artworks from the upper Missouri River region. The scarcity of existing objects, and as a result, limited visual references create significant challenges in making specific attributions and comparisons from this region and period of time.

Still, some of the defining features of northern plains groups (at the time of contact) formed as a response to disease and the resulting loss of life. One scholar notes that “The social fluidity whereby tribes or divisions of tribes split apart and regrouped may have developed as a means of coping with catastrophic population loss.”[6] Epidemics affected all aspects of life for plains groups. For example, warriors could not train and military technology could not be developed if the group was sick and dying.[7]

Assiniboine artist, Shirt, c. 1830. Leather, beads, quills, paint, human hair, and horse hair, 60 x 75 in. (Denver Art Museum)

Museum collections and the paintings of Catlin and Bodmer

We see evidence of the enormous population loss in men’s shirts from this time period. In this context, men’s shirts refer to a shirt worn by a warrior into battle or during festivals (so not daily use), and which are decorated with hair fringes (human and horse), ermine tails, quillwork, and beadwork. While we may know they were made by artists from this region, assigning an attribution to a particular community is difficult for several reasons. Few pre-1850 arts by Indigenous artists from any region exist in U.S. museums, although some can be found in international museums (including in the Paul Kane collection in the Manitoba Museum in Winnipeg and the collections of Prince Maximiliam of Wied in museums located in Berne, Berlin, and Stuttgart). Some collections exist from Lewis and Clark’s expedition from 1804–1806, but William Clark’s personal collection, once housed in his home in St. Louis until his death in 1838, went missing around this time and its whereabouts remains unknown to this day.[8] The total number of works of American Indian arts from the Plains before 1850 remains quite small.

When you narrow down these early nineteenth-century arts to shirts, and those exclusively from the upper Missouri River region, there are few examples with which to compare, and even fewer with documentation. Of the 40 shirts in the collection of the Denver Art Museum from the Plains and Plateau regions, only two date to around 1830 or before. One is attributed to an Assiniboine artist and the other is dated to 1800–1820, and is the focus of this discussion.

Left: George Catlin, Stu-mick-o-súcks, Buffalo Bull’s Back Fat, the Head Chief of the Blood Tribe (Blackfoot), 1832, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 60.9 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum); right: George Catlin, Peh-tó-pe-kiss, Eagle’s Ribs (Blackfoot), 1832, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 60.9 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

With limited examples, great losses in the continuity of Indigenous knowledge, and works that predate photography by decades, the main way to identify these shirts is through the written reports of fur traders and explorers, as well as the paintings of George Catlin and Karl Bodmer who traveled in the region in the 1830s.

Two Assiniboine men. Left: Karl Bodmer, partially completed portrait of Noapeh (Troop of Soldiers), 1833, watercolor; right: Karl Bodmer, an unidentified Assiniboine man, 1833, watercolor

Interpreting what the shirt says about the man who wore it

In December of 2019 the Denver Art Museum received two shirts from the Upper Missouri region of the Plains as gifts from a private collector: one dating to around 1800–1820 and the other to around 1855. The earlier of these two shirts is without question the single most significant work to come into DAM’s Native arts collection in decades.

Quilled war shirt (front), c. 1800-1820. Native tanned hide, porcupine and possibly bird quills, plant material, red trade cloth, dyes, and sinew. 34 x 43 inches (Denver Art Museum)

It is exceedingly rare and among the earliest shirts from the Upper Missouri River region in existence. The shirt’s lack of beadwork, minimal use of Bayetta trade wool, and quilled design elements point to its early creation date and connection to this region.

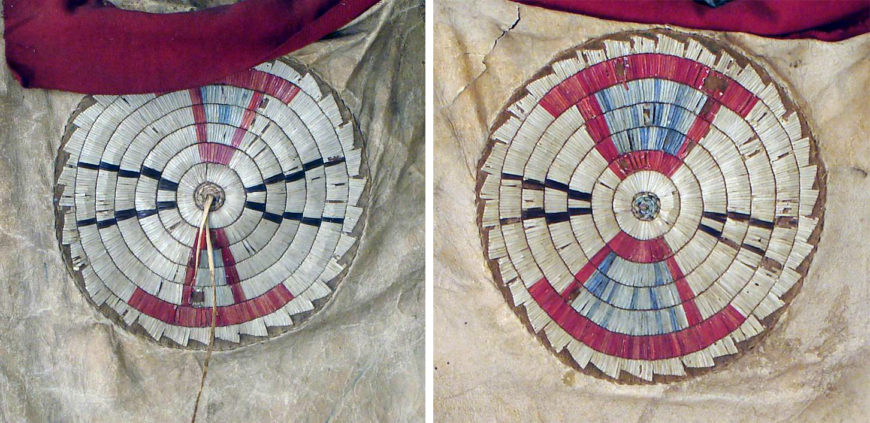

Detail of the front and back rosettes, quilled war shirt (front), c. 1800-1820. Native tanned hide, porcupine and possibly bird quills, plant material, red trade cloth, dyes, and sinew. 34 x 43 inches (Denver Art Museum)

This fringed “poncho” style shirt with red trade wool rectangular “bibs” was made using Native tanned mountain sheep hides and sewn using sinew (animal tendons or ligaments used as thread). On both the front and back of the shirt are saw-tooth edged medallions (rosettes) and over each shoulder and along each sleeve are three quilled lanes with geometric patterning.

Detail of a sleeve, quilled war shirt, c. 1800–1820. Native tanned hide, porcupine and possibly bird quills, plant material, red trade cloth, dyes, and sinew. 34 x 43 inches (Denver Art Museum)

While little was recorded about the meanings of such elements, the medallions are commonly considered representations of forces of nature, such as the sun or powerful winds. It has also been suggested that the designs on medallions, such as those seen on this shirt and many others from this region, may represent the wings of a Thunderbird, a sacred being for many Plains tribes.

The central medallions are made from porcupine quills, likely plant material, and possibly also bird quills. Porcupine quillwork is a technique Indigenous to North America and was prevalent prior to the trade of European manufactured glass trade beads. Today this technique is experiencing a resurgence among many Native artists. The materials used on this shirt (as well as materials not used, such as glass beads) suggest it was made just as trade between fur trappers and Native people began in the central part of North America.

Detail of faces, coup sticks, and bear claws, quilled war shirt (back), c. 1800–1820. Native tanned hide, porcupine and possibly bird quills, plant material, red trade cloth, dyes, and sinew. 34 x 43 inches (Denver Art Museum)

What is among the most exciting elements of this shirt are a series of pictographic and geometric drawings found on either side. If you look closely you will see faint indigo drawings of six heads, above which are floating lines. Below the heads is a row of four bear paws, and to the right are three pipes. The exact meaning of these elements was not recorded; however, based on Indigenous knowledge and with the help of Dr. Timothy McCleary, a colleague from Little Bighorn Tribal College at Crow Agency in Montana, we believe we know what they mean.

The heads with floating lines likely refer to counting coup, or striking an enemy with a stick. When a warrior touched his enemy with his coup stick, it was regarded as an act of extreme bravery because he had to get close to his opponent. The pipes may suggest how many times the shirt’s owner led successful war parties. The bear paws show how many Plains grizzlies the owner of the shirt had killed. Drawings and explanations in American ethnologist Garrick Mallery’s 1889 publication Picture Writing of the American Indians demonstrates how widespread such imagery was among Plains artists in the late nineteenth century. Mallery’s text reproduces a drawing and accompanying explanation by an Oglala Lakota man that explains the meaning of pipes depicted similarly to what we see in the shirt, as well as other design elements recorded on it.

Detail of quilled war shirt (front), c. 1800–1820. Native tanned hide, porcupine and possibly bird quills, plant material, red trade cloth, dyes, and sinew. 34 x 43 inches (Denver Art Museum)

The designs on the front of the shirt tell even more specific stories about the owner. Here, we find drawings of five X-like forms arranged below the medallion. These are war honor marks. From left to right, we can read these to recount the original owner’s achievements in war. The first shows that the warrior was the third person to touch a live enemy in battle (counting coup). The next shows that after he had dismounted an enemy, the owner of the shirt captured the enemy’s horse. The next two Xs show he was the fourth person to count coup on an enemy during battle. Then the last shows that he was again the third to count coup on an enemy. Mallery recorded variations of these designs and meanings as told to him by Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara consultants.

These marks were common ways to record war deeds among the Native people of the Upper Missouri River region and are found on clothing, tipis, and in rock art. The Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, and Crow people are well known for their use of this X to represent an enemy. While a few other tribes also used this imagery, this form with the associated hash marks (denoting the number of coups) and horse hoof prints are all from one of the Upper Missouri River tribes.

Ongoing challenges

Indigenous people have faced countless challenges to their ways of life since the arrival of settler-colonial people. Sickness and disease took its toll, but so did forced relocation, land allotment that broke up clan and society structures, prohibitions against ceremonies and religions, traumatic boarding school experiences, broken treaties, and institutional and structural racism, to name a few. Each of these created seemingly insurmountable hurdles for Indigenous people to overcome.

Many of these challenges still exist. The Navajo Nation has been hit hard by COVID-19. Two Lakota reservations are under attack from the governor of South Dakota for the medical checkpoints they put up on their own roads to protect their citizens from the spread of this disease. Generational trauma from past experiences warns them to protect themselves. Elders are the keepers of knowledge and they are most at risk. The transmission of intergenerational knowledge of all forms, visual arts included, is difficult during such times. But this knowledge still exists in communities. These art forms are still being created by brilliant and innovative Indigenous youth. And this should give us hope for the future.

Notes:

[1] Linea Sundstrom, “Smallpox Used Them up: References to Epidemic Disease in Northern Plains Winter Counts, 1714–1920,” Ethnohistory 44, no. 2 (Spring, 1997), pp. 305–343

[2] Sundstrom, “Smallpox Used Them up,” p. 308

[3] It has been suggested that the Mandans, Arikaras, and Hidatsas from the upper Missouri River region lost a combined 70% of their populations. Donald J. Lehmer, “Epidemics among the Indians of the Upper Missouri,” in Selected Writings of Donald J. Lehmer, ed. W. Raymond Wood, Reprints in Anthropology no. 8 (I977), pp. 105–11

[4] Clay Jenkinson, “Smallpox and Indians: When Pandemic Warnings Go Unheeded,” in Governing, April 22, 2020, https://www.governing.com/context/Smallpox-and-Indians-When-Pandemic-Warnings-Go-Unheeded.html

[5] Jenkinson, “Smallpox and Indians”

[6] Sundstrom, “Smallpox Used Them up,” p. 325

[7] Sundstrom, “Smallpox Used Them up,” p. 325.

[8] Norman Feder, American Indian Art Before 1850, Denver Art Museum Summer Quarterly (1965), p. 5; National Park Service, Department of the Interior, “William Clark’s Indian Museum: A Tradition Continued,” in The Museum Gazette (October 1997), p. 5

Additional resources

Learn more about the Denver Art Museum’s collection of Indigenous Arts of North America

Learn about Lakota Winter Counts in this Smithsonian video

Learn more about narrative art of the Plains from the National Museum of the American Indian

Colin Taylor, “Analysis and Classification of the Plains Indian Ceremonial Shirt: John C. Ewers Influence on a Plains Material Culture Project,” in Fifth Annual Plains Indian Seminar in Honor of Dr. John C. Ewers, ed. George P. Horse Capture and Gene Ball (Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, 1980)

David W. Penney, Art of the American Frontier: The Chandler-Pohrt Collection (Detroit Institute of Arts, 1992)

George Horse Capture and Joseph D. Horse Capture, Beauty, Honor and Tradition: The Legacy of Plains Indian Shirts (University of Minnesota Press, 2001)

Colin F. Taylor, Buckskin & Buffalo: The Artistry of the Plains Indians (New York: Rizzoli, 1998)

George Catlin and His Indian Gallery (Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2002)

David C. Hunt and Marsha V. Gallagher, Karl Bodmer’s America (Joslyn Art Museum, 1984)

Emma I. Hansen, Memory and Vision: Arts, Cultures and Lives of Plains Indian Peoples (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2007)

Garrick Mallery, Picture Writing of the American Indians, Volume I (New York: Dover Publications, 1972). A reprint of the paper “Picture Writing of the American Indians,” in the Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1888-89, by J. W. Powell, Director, published by the Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. in 1893

Norman Feder, “Plains Pictographic Painting and Quilled Rosettes,” in American Indian Art Magazine, Vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 54–62

Colin F. Taylor, Saam: The Symbolic Content of Early Northern Plains Ceremonial Regalia, (Verlag Fur Amerikanistik, 1993)

Norman Feder, Two Hundred Years of North American Indian Art (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1971)

John F. Taylor , I977, “Sociocultural Effects of Epidemics on the Northern Plains: 1734–1850,” Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology 7 (4): pp. 55–81