Arts of the Islamic world, the early period: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 28

Continuity and Innovation: Early Islamic art and architecture of the Umayyads and Abbasids

Great Mosque of Kairouan prayer hall façade (photo: Damian Entwistle, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Artworks and buildings have been produced by and for Muslims across the world from the 7th century to the present, and it would take many books to do justice to their full range. This chapter looks at some of the art produced immediately before and during the first few centuries of Islam, in West Asia and North Africa. It focuses on the cultures of the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties, which were the first two major caliphates.

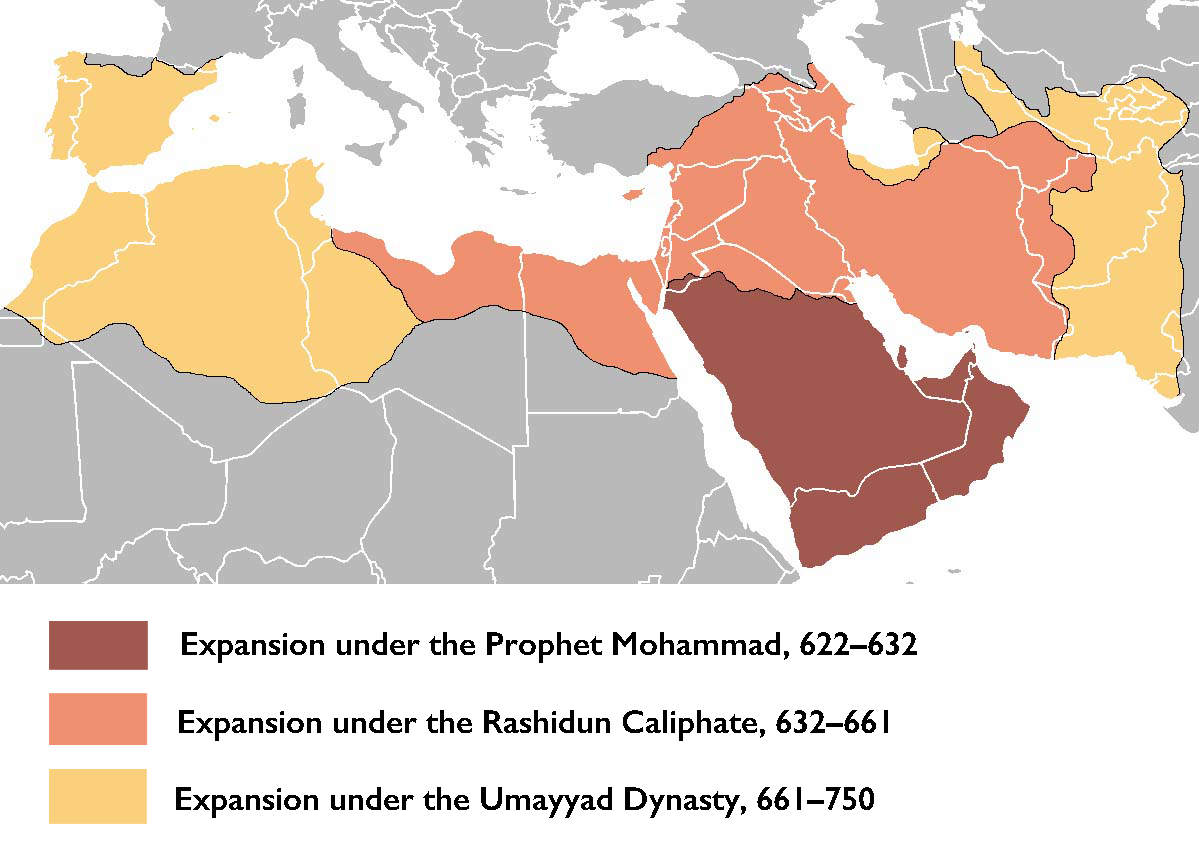

Map indicating the phases of expansion under the Prophet Mohammad, the Rashidun caliphate, and the Umayyad Dynasty

Map of the Mediterranean and west Asia in the 9th century

The art produced in these early centuries is wonderfully varied, and different Islamic lands had their own artistic traditions. Techniques or materials could be associated with specific cities, for example Nishapur in Iran was famous for producing colorful glazed ceramics. Such local identities could be important to craftspeople, who sometimes recorded their hometowns in inscriptions on artworks.

There were also long-distance connections, within and beyond the Islamic world. People and goods moved overland from one part of the caliphate to another, sometimes using the roads and hostels maintained for the barid (the official postal system). Longer journeys usually took place by ship. Although the level of trade across the Mediterranean Sea had dropped after the fragmentation of the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries, it never stopped completely, and ships also carried merchandise back and forth between the West Asia, India, Indonesia, and China.

Despite regional differences, broad similarities can be found—in the architecture of mosques, the decoration of textiles, or the marking of verses in Qur’ans—which tell us that some cultural conventions were shared across large areas. The Great Mosques of Kairouan and Aleppo are separated by 200 years and 1,500 miles, but both have large courtyards surrounded by porticos, and arched entrances to the prayer-halls (the latter shown towards the right of both images below).

The Great Mosques of Kairouan, Tunisia, 9th century (left), and Aleppo, Syria, 11th–14th century (right) (photos: Sean Leatherbury and Ross Burns/Manar al-Athar)

There was also a balance in the early Islamic period between continuity and innovation. On the one hand, some objects and compositions are almost indistinguishable from Sasanian or Byzantine designs of previous generations, and this is not surprising given that many of the artists would have been trained in these traditions. For instance there are similarities in the designs of the two silver dishes shown below, in the overhanging grape vine and the central image of a figure holding a drinking bowl, although one is early Islamic in date and one is several centuries earlier.

Left: Gilded silver dishes from the Sasanian Empire, 2nd–3rd century; right: from the early Islamic period of rule in the same region, 7th–8th century (photos: © Trustees of the British Museum)

On the other hand, there were inventions. There were new kinds of visual display, such as the decorative use of Arabic script, and technological changes, such as the new recipes developed by ceramicists and glassmakers at the Abbasid courts.

Left: Fragment of statue from Umayyad palace of Mshatta; right: detail of bronze brazier with Dionysiac imagery from Umayyad palace of al-Fudayn, both from Jordan, first half of the 8th century (Jordan Archaeological Museum, Amman; photos: Beatrice Leal)

The 8th and 9th centuries also saw the reinvention of some ancient Greek and Roman cultural traditions, such as the use of figural sculpture and an engagement with classical mythological subjects. Both objects above were commissioned for Umayyad palaces and both use imagery from the classical tradition; the woman carrying a piece of fruit may represent one of the seasons, and the man on the brazier is likely to be the god of wine Dionysus, or one of his followers.

The mix of tradition, innovation, and reinvention depended on the function of the artwork, the interests of the patron, the presence of artists trained in a particular way, and the availability of materials for them to work with, among other things. Iconography also varied according to setting—some types of images were seen as appropriate for houses or palaces but not for mosques, for instance.

Patrons, makers, and materials

In addition to describing the main trends of development in early Islamic culture, each section of this chapter will present an artwork in relation to three questions. These are broad questions that can be asked of any object or building, from any time or place, so they can help to highlight comparisons and contrasts. Firstly, who commissioned objects and buildings? Secondly, what do we know about the people who did the work? And thirdly, what were the social, technological, or symbolic considerations behind the choice of one material over another?

Read an introductory essay

/1 Completed

Before Islam

This section looks in more detail at the pre-Islamic period, to set the political and cultural scene into which Islam emerged in 7th-century Arabia. Arabia has not always been given much importance in the story of Islamic art; previous generations of scholars described its visual culture as weak and unimpressive. [1] This picture has been modified partly by archaeological discoveries and partly by changes in attitude. Some aspects of Arabian art and architecture were distinctive to the region, from massive rock-cut shrines to delicate painted ceramics. Other art forms, such as stuccowork, were inspired by neighboring cultures but adapted to local settings.

Stucco panel from church at al-Qusur, Kuwait, 8th century (photo: © Mission archéologique franco-koweïtienne de Faïlaka/Hélène David-Cuny)

An 8th-century stucco panel from the church of al-Qusur hints at the diverse visual culture of pre- and early Islamic Arabia. The patrons belonged to one of the Christian communities living along the coast of the Persian Gulf, and like congregations elsewhere they invested in the decoration of their churches, possibly as a collective enterprise. All the surviving archaeological evidence for churches in the region dates to the early Islamic period (as this panel does), but according to written sources Christian communities existed from the 4th century C.E., and it is probable that earlier churches were similarly decorated. The makers may have been local to Arabia, but they probably also had links to workshops in what is now Iran, as the material and motifs of the molded plaster were common in the Sasanian world. Stucco paneling of this kind was equally widely used in Umayyad and Abbasid palaces.

In late antiquity large powers surrounded Arabia—the Sasanian Empire to the east and the Byzantine Empire to the west—and as the decorated plasterwork shows, this had an artistic impact. In the 7th century, Muslim forces conquered the entire Sasanian territory and large parts of Byzantium. Early Islamic art incorporated many elements from both traditions.

Byzantine and Sasanian visual cultures didn’t exist in isolation; some motifs and techniques were popular in both regions, and even further afield. The combination of styles in many early Islamic monuments was a continuation of this artistic mixing.

Read essays about art before Islam

Pre-Islamic Arabia: The pre-Islamic Arabian Peninsula had a complex artistic and religious history.

Read Now >

Sasanian art: Many of the elite artforms in the Sasanian Empire continued to be valued in the early Islamic period.

Read Now >

Byzantine art: The Byzantine empire and the caliphates were political rivals, but each had an influence on the art and architecture of the other.

Read Now >

Cross-cultural artistic interaction in the Middle Byzantine period: Some early Islamic art was inspired by Byzantine examples, which in turn used conventions shared with other cultures.

Read Now >/4 Completed

The beginnings of Islam

The Prophet Muhammad started preaching during the 610s in Mecca in western Arabia, and established the first Muslim community in Medina in 622. Over the next few decades, Muslim armies conquered a territory stretching over 3,000 miles. Some new military towns were founded, such as Basra and Kufa in what is now Iraq. The administration of existing cities continued—with some minor changes, such as new issues of coins.

Silver dirham minted at Bishapur, Iran, mid-7th century (Classical Numismatic Group, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The patron of the mid-7th century silver dirham shown here was a Muslim governor of Fars province (in modern-day Iran), during the reign of one of the early caliphs, but the portrait on the coin is not of either of them. Instead the figure is the pre-Islamic ruler, the Shahan Shah, and the reverse of the coin shows a Zoroastrian fire altar. The makers had probably worked in the mint of Bishapur before the conquest, and may have reused the same dies as before. There was a subtle addition to the design, however; the Arabic inscription beside the portrait reads bismillah, “in the name of God.” There was an increase in precious metal mining in the early Islamic period, and silver coins gradually circulated throughout the caliphate, whereas previously they were rare outside Iran.

As this coin shows, Muslim administrators commissioned objects and images for the business of government. But the first wave of expansion of Islam was not marked by grand artistic or architectural projects; in the new settlements the first mosques were simply open spaces for prayer. There were exceptions, however, including two essential elements of Islamic material culture: the Kaaba and the Qur’an.

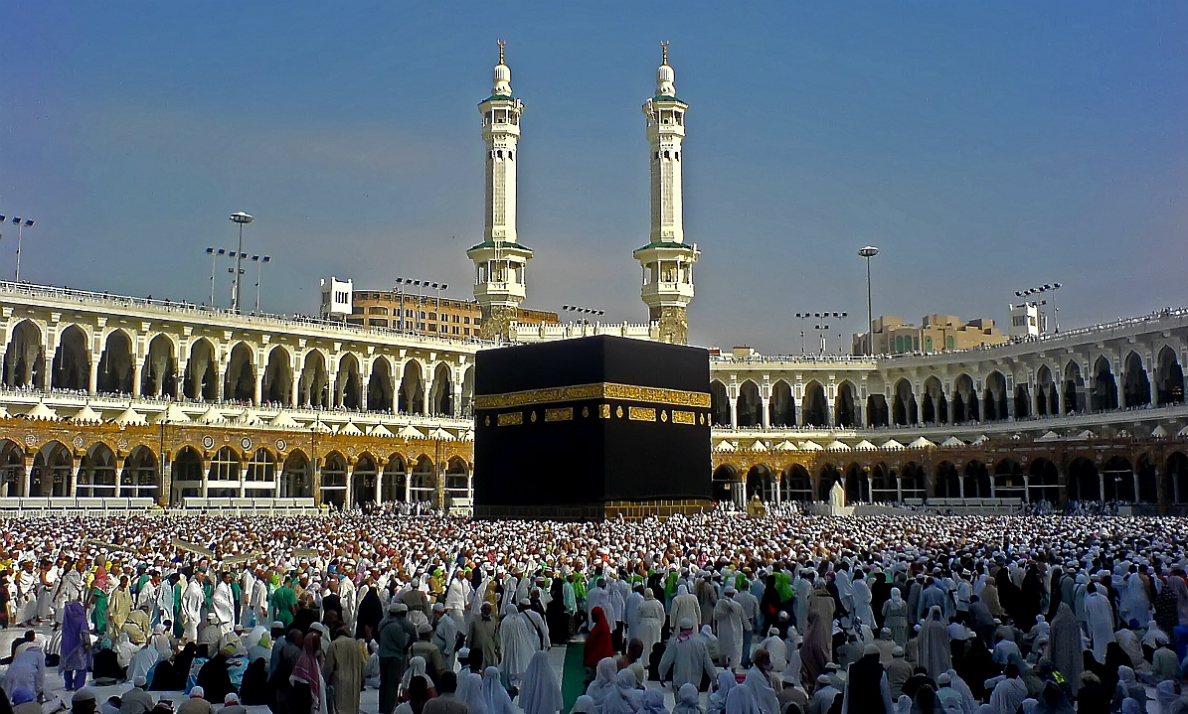

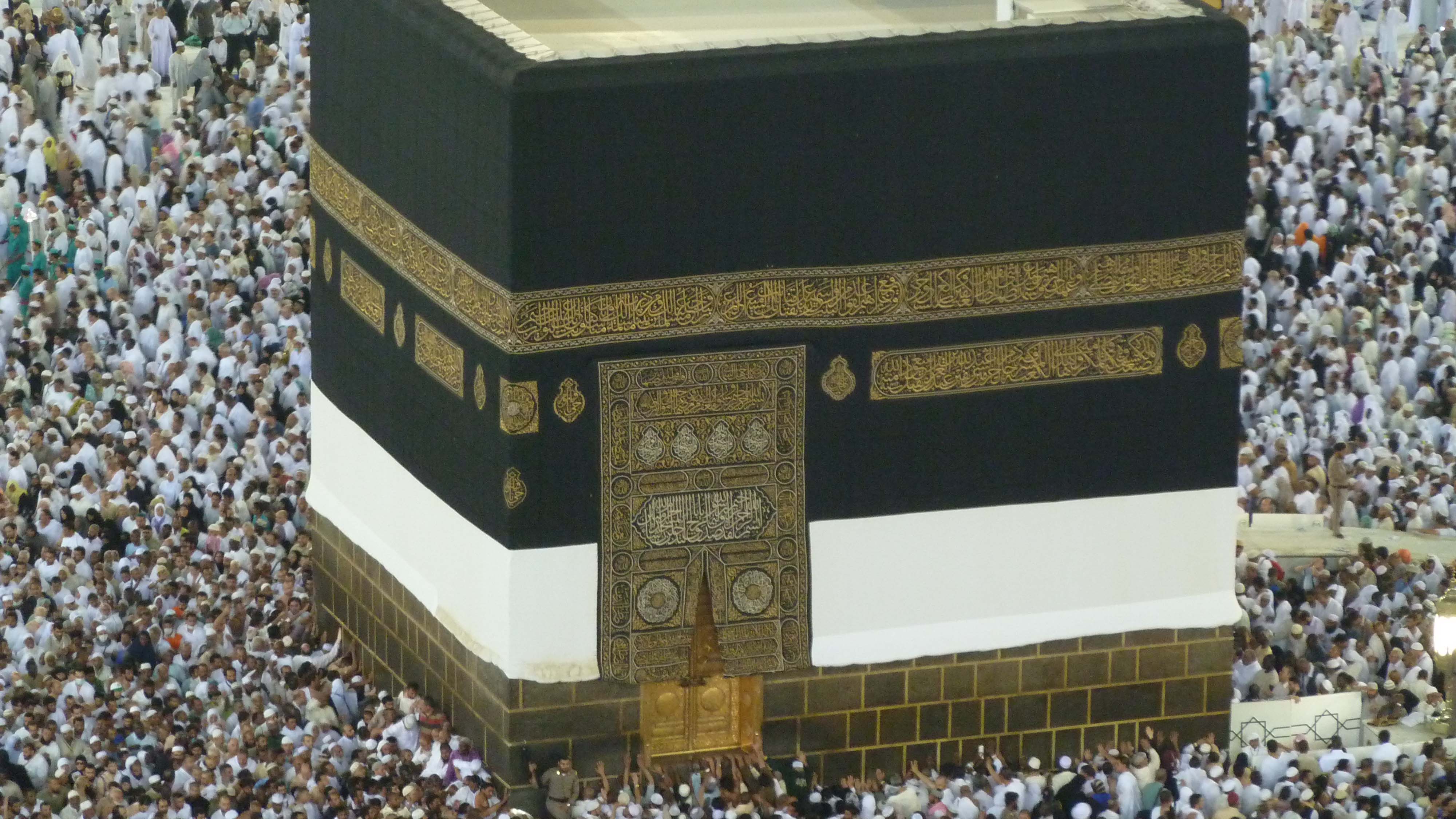

The Kaaba, granite masonry, covered with silk curtain and calligraphy in gold and silver-wrapped thread, pre-Islamic monument, rededicated by Muhammad in 631–32 C.E., multiple renovations, Mecca, Saudi Arabia

The Kaaba was modified several times in the 7th century, by different and sometimes rival patrons, as the needs of the expanding pilgrimage center were set against a desire to replicate the original (but by then already long-lost) form of the shrine. During the reign of Uthman (644–56) the Qur’an began to be written down in codices, rather than being transmitted only in spoken form. The process of writing contributed to the standardization of the text. Qur’anic manuscripts from this period survive, a few with chapters separated by simple decorations, perhaps to aid memorization of the text.

Read essays about the beginnings of Islam

Introduction to Islam: Some aspects of Islamic material culture began during the lifetimes of Muhammad and his initial successors.

Read Now >

Introduction to mosque architecture: The first mosque was the Prophet’s house in Medina; more ornate architectural settings for prayer were developed later.

Read Now >

The Kaaba: The Kaaba is the central shrine of Islam, and has been rebuilt many times over the centuries.

Read Now >

The Qur’an: The prophetic revelation was initially spread in spoken form, and was recorded in a book format after Muhammad’s death.

Read Now >/4 Completed

The Umayyad caliphate (661–750)

If the conquest period didn’t produce much elaborate art and architecture, the following century made up for it—many of the most impressive early Islamic monuments date to the Umayyad era. Even relatively modest Umayyad buildings might be given a touch of grandeur by the use of expensive materials, such as glass mosaic.

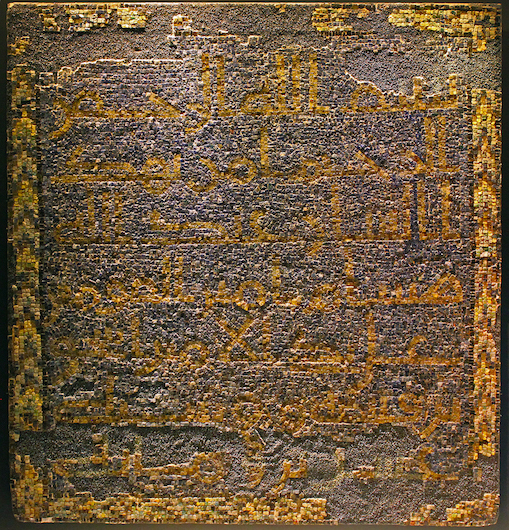

Dedicatory inscription of market in Beth Shean, 737–38, Israel Museum, Jerusalem (photo: Sean Leatherbury/Manar al-Athar)

An eighth-century mosaic inscription from Beth Shean (in present-day Israel) illustrates several characteristics of Umayyad art. It commemorates the building of a marketplace under the patronage of the governor Ishaq bin Qabisa and caliph Hisham. Many of the early caliphs invested in projects like roads, canals and markets; these were ideological acts as well as practical ones, demonstrating the resources of the regime. As with the silver coin discussed above, the makers were probably non-Muslim; most local mosaicists would have been Christian or Jewish. The inscription is written in Arabic, however, perhaps indicating the involvement of Muslim artisans, as well as the increasing use of the language for official purposes. The medium of glass mosaic had a long tradition in the Levant, and was adopted for many of the most prestigious Umayyad buildings, such as the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosque of Damascus.

Mosaic arches with acanthus motif, Great Mosque of Damascus, Syria (photo: Judith McKenzie/Manar al-Athar, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

While Umayyad religious buildings—like the two mentioned above—were the most visible artistic interventions of their time, it is important to remember that these are only one aspect of Islamic material culture. There were also distinctive forms of secular buildings, like palaces and bathhouses, as well as objects from curtains to tableware. Wool textiles like the one shown here would have been valuable possessions but were nonetheless fairly widespread, and unglazed jugs painted with simple designs might be owed by almost any household.

Left: fragment of tiraz, 7th–8th century, silk, from a cemetery at Akhmim (Egypt), 21.5 x 15.2 cm (The V&A); right: painted jug, late 7th or 8th century, found at Jerash, Jordan (photo: Beatrice Leal)

Read essays about art made under the Umayyads

The Umayyads, an introduction: Umayyad rulers sponsored art forms ranging from new designs of coins to large congregational mosques, creating a coherent dynastic image.

Read Now >

The Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra): This was one of the first explicitly Islamic monuments, built in Jerusalem during the reign of ‘Abd al-Malik.

Read Now >

The Great Mosque of Damascus: Caliph al-Walid I, ‘Abd al-Malik’s son, made an equally striking architectural statement with a huge mosque in the center of Damascus.

Read Now >

The Great Mosque of Córdoba: After the Abbasids defeated the Umayyads in Syria, some of the dynasty reestablished themselves as rulers in Spain.

Read Now >/4 Completed

The Abbasid caliphate (750–13th century)

In 750 the Umayyad dynasty was replaced by the Abbasids. The new rulers founded cities, notably Baghdad and Samarra in Iraq, and the artisans who gathered there developed characteristic styles of working.

Great Mosque of Samarra, Iraq (photo: Taisir Mahdi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Investment in older sites also continued, for example many Abbasid caliphs restored buildings in the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, and artists sometimes traveled across hundreds of miles to take part in these projects. The caliphs were not the only patrons; as before, regional governors and wealthy individuals also sponsored works of art. Another Umayyad site which continued to attract sponsorship was the Great Mosque of Damascus.

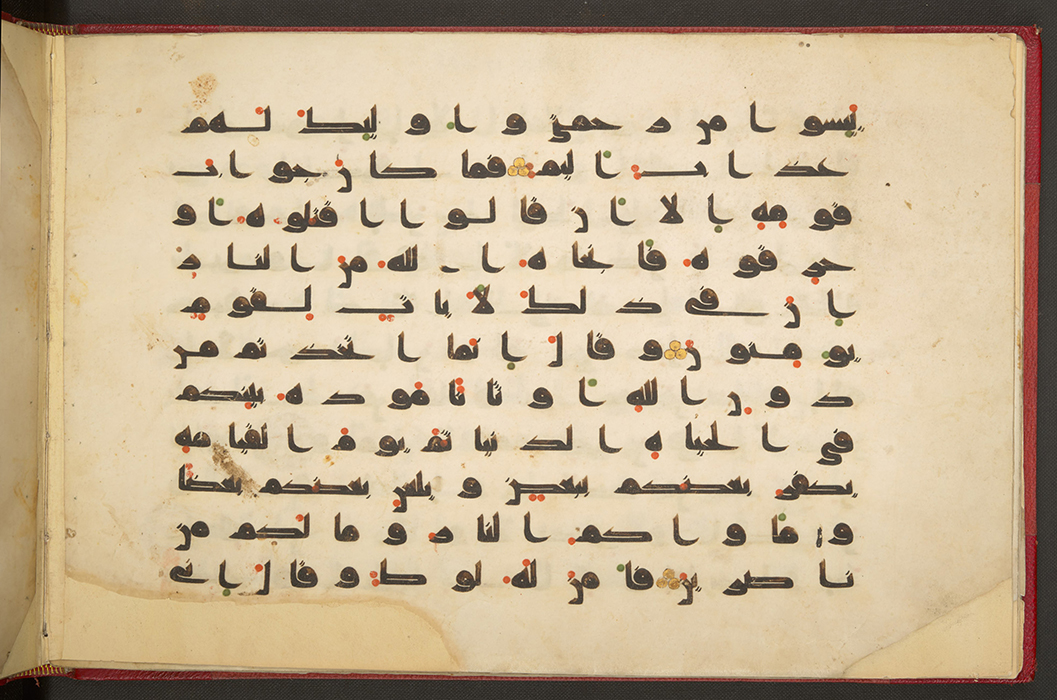

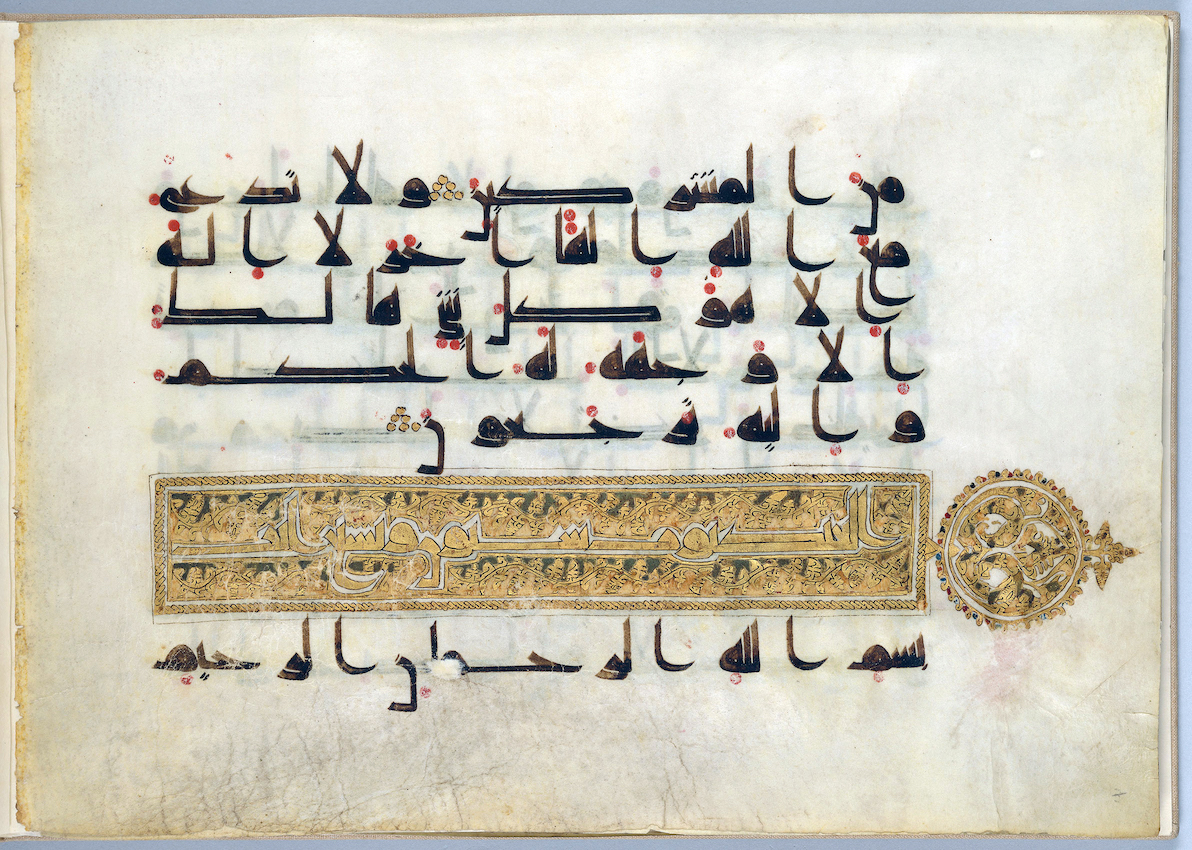

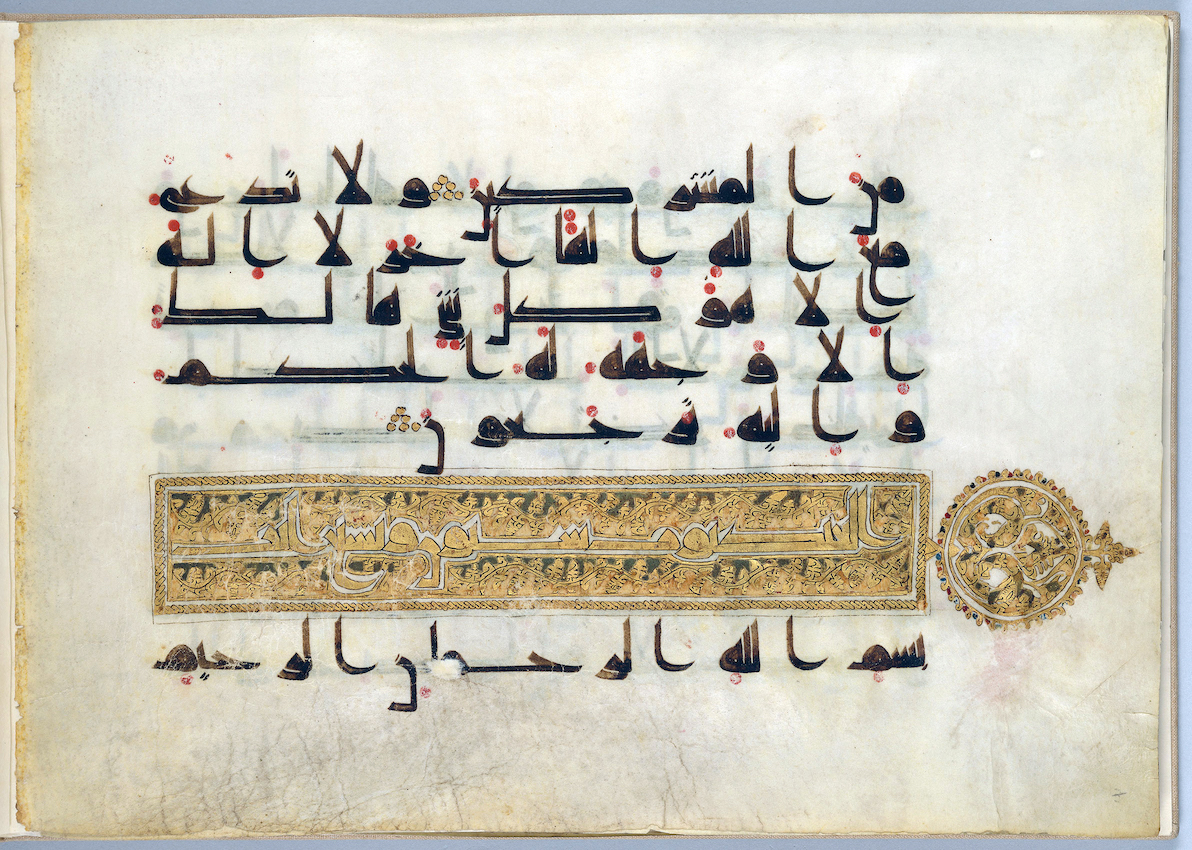

Folio from Qur’an, before 911, possibly made in Iraq (The Morgan Library and Museum, New York, MS M.712, fol. 19v)

In 911 a Qur’an was donated to the Great Mosque of Damascus. The patron, ‘Abd al-Mun’im, may have been a local aristocrat, or maybe an official who had traveled to Damascus. The scribes were highly trained calligraphers, probably working in one of the new Abbasid cities in Iraq. The book was in the latest style, with long horizontal pages, and like many top-end Abbasid Qur’ans it was decorated with gold. The use of precious metals was rare in 8th-century Qur’ans, but increasingly common in the 9th and 10th centuries, partly to enhance the sacred text but also as a display of wealth.

From the 10th century, the Abbasid caliphate was surrounded by other Islamic states, sometimes in conflict with them and sometimes with more diplomatic relations. The last two essays in this section highlight artworks from the courts of two of these powers, one from al-Andalus in the far west of the Islamic world, and one from the east, in the Ghaznavid empire centered in modern Afghanistan.

Read essays about art under the Abbasids and other powerful courts

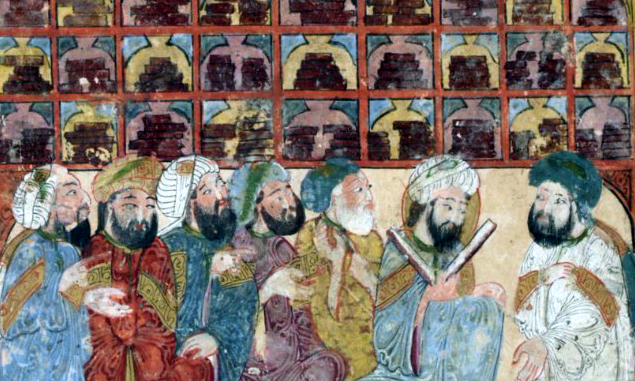

Arts of the Abbasid Caliphate: The Abbasid courts attracted scholars and artists from across the Islamic world.

Read Now >

Samarra: the Abbasid caliphs spared no expense to build a palatial city of grand buildings and sprawling residential complexes.

Read Now >

Folio from a Qur’an: Abd al-Mun’in ibn Ahmad donated this Qur’an to the Great Mosque of Damascus.

Read Now >

Dado Panel, Courtyard of the Royal Palace of Mas’ud III: This marble panel was part of the 12th-century Ghaznavid palace near Kabul.

Read Now >/5 Completed

As the rival caliphates and sultanates multiplied during the so-called Middle Ages, the diversity of styles and techniques of Islamic arts did too. Nonetheless, the achievements of the Umayyad and Abbasid periods continued to inspire artists for centuries to come.

Notes:

[1] The art historian Oleg Grabar wrote that “the living architecture of Central Arabia was not an impressive one” and referred to the “visual weakness of [Islam’s] Arabian past”: The Formation of Islamic Art, 1973 (revised 1987), New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 75, 94.

Key questions to guide your reading

What are the factors that might encourage artistic innovation on the one hand, or sticking to traditional conventions on the other?

What does it mean to say that an artwork or an artistic tradition is influenced by another one?

What can the choice of materials tell us about what an object or building was used for, and who it was for?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat are the factors that might encourage artistic innovation on the one hand, or sticking to traditional conventions on the other?

What does it mean to say that an artwork or an artistic tradition is influenced by another one?

What can the choice of materials tell us about what an object or building was used for, and who it was for?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

caliph

Islam

Kaaba

mihrab

minaret

minbar

mosaic

mosque

qibla

Qur'an (also spelled Koran)

Learn more

Learn about gold in the Qur’an

The vibrant visual cultures of the Islamic West, an introduction

Agnieszka Lic, ‘Why Study Stucco? The Importance of Stucco Decorations for Christian Communities of the Gulf in the Early Islamic Period’, Le carnet de la MAFKF. Recherches archéologiques franco-koweïtiennes de l’île de Faïlaka (Koweït), (2016).