The Abbasid period started with a revolution. Caliphs of the earlier Umayyad dynasty had ruled for almost a hundred years after they assumed power in 661 (after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 C.E.), and over this time discontent gradually built up against them, both from rival elites and from large sections of the general population. After three years of open fighting the last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II, was assassinated in 750. This is when the Abbasid caliphate began.

The end of the Abbasid era is harder to define. Though territory and power were lost to various competing dynasties from the late 10th century, there were still rulers calling themselves Abbasid caliphs in the 1200s. This essay will focus on the high point of their power—the late 8th to 10th centuries—and will look at three aspects: cities, technologies, and books.

A map of the Abbasid Caliphate around 850 C.E., with cities circled in red that are discussed in this essay (map: Cattette, CC BY 4.0)

Cities

After the revolt in 750, the Abbasids moved the capital from Damascus in Syria, where the Umayyads had been based, to Kufa in Iraq. Then, in 762 the caliph al-Mansur founded a new imperial city on the banks of the Tigris—Madinat al-Salam or the City of Peace, also known as Baghdad.

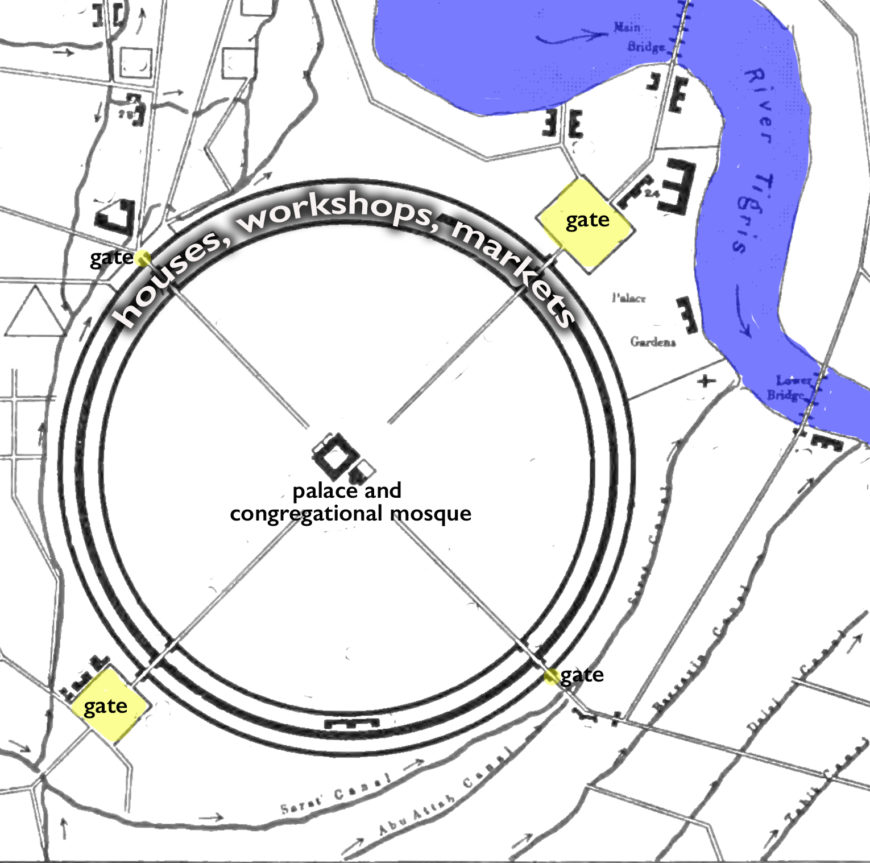

Round City of Baghdad in the time of Mansur, Abbasid caliphate, adapted from Guy Le Strange, Baghdad During the Abbasid Caliphate from Contemporary Arabic and Persian Sources. Oxford: Clarendon Press, Map II (1900; public domain)

The city was carefully planned to express perfection and order, as a display of the qualities of the new regime; it was circular in plan, with four main gates, one at each compass point, similar to the 3rd-century Sasanian city of Gur, whose outlines can still be seen in the fields around Firuzabad in Iran. The center of Baghdad was left largely open around the palace and congregational mosque, while the houses, workshops, and markets were arranged in a ring inside the walls.

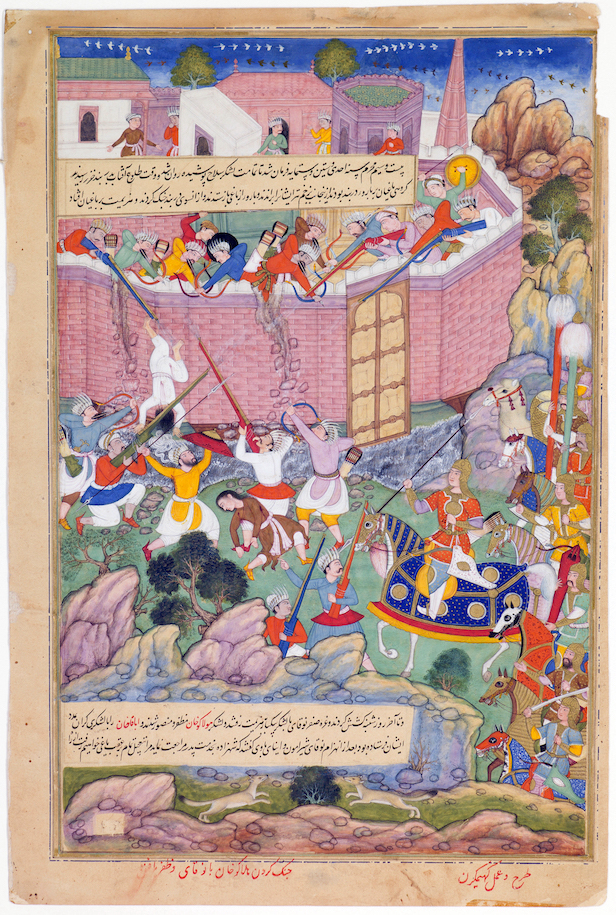

Khem Karan, view of the Siege of Baghdad in 1258, folio from an illuminated manuscript of the History of Genghis Khan, 1596, ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, Lahore, Punjab province, Pakistan, Asia, 34.9 x 22.5 cm (Saint Louis Art Museum)

No remains of the round city have survived, partly due to the siege and assault on the city by the Ilkhanid Mongol army in 1258, and partly due to the construction of the modern city on top of the older structures, but we know something of its appearance from medieval descriptions. Some were written by authors born in Baghdad, such as al-Ya’qubi and al-Katib al-Baghdadi, and some by those who had moved there, attracted by the facilities for scholars, such as al-Jahiz, who reported that:

I have seen the great cities . . . in the districts of Syria, in Bilad al-Rum and in other provinces, but I have never seen a city of greater height, more perfect circularity, more endowed with superior merits or possessing more spacious gates or more perfect defenses than the [Baghdad] . . . of Abu Jafar al-Mansur. Description by al-Jahiz, reported in the Ta’rikh Baghdad (History of Baghdad) by al-Khatib al-Baghdadi [1]

Among the treasures in the palace was an automata in the shape of a tree made of gold and silver, whose branches would move as if swaying in the wind, while the model birds sitting on them would sing. [2] One of the aims of such luxury was to advertise the wealth and strength of the Abbasid caliphate to rival powers, such as the Byzantine Empire based in Constantinople—and in this the patrons were successful. After hearing an ambassador’s report of the palace and its furnishings, the mid-9th-century, Byzantine emperor Theophilus was so impressed that he commissioned one intended to imitate it, although the site is not known with certainty today.

Another early Abbasid project was the twin city of Raqqa-Rafiqa in Syria. Raqqa had existed for centuries, and in 770 al-Mansur ordered the construction of a new and more defensible settlement, Rafiqa, less than half a mile away, as part of a larger project of creating fortified sites near the border with Byzantium. The new part of the town, Rafiqa (Raqqa and Rafiqa eventually merged as one urban center) was given a substantial wall of brick, nearly three miles long, with monumental entrance gates.

In the 780s caliph Harun al-Rashid chose Raqqa-Rafiqa as his capital, and the architecture of the twinned towns took on a more elegant aspect, with enhanced decorative as well as defensive features. Archaeologists have discovered more than twenty palaces, mostly outside the walled enclosure, dating to the reigns of Harun and his son al-Mu’tasim.

Capital with Leaves, late 8th century, alabaster, gypsum; carved in relief, made in Syria, probably Raqqa, 28.6 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The capital shown here comes from one of these palaces. It has a stylized version of an acanthus-leaf design that had been popular throughout late antiquity; in this reimagined form, the leaves also form abstract patterns. Other pieces of carved stone and molded stucco were found with similar designs, showing that the decor of the late 8th-century palaces was carefully coordinated by skilled artisans.

Samarra, founded by the caliph al-Mu’tasim in 836, was different from either of the earlier sites. Although it was the size of a city, covering more than twenty square miles, it was devoted to the Abbasid court, with palaces, pavilions, mosques, monumental avenues, barracks, gardens, pools, and three horse-racing tracks. There were also areas of more modest housing, but the heart of Samarra was ceremonial. Despite the huge outlay of resources, the site was fully occupied for less than sixty years. The 860s saw significant political instability at Samarra caused by competing military factions in the caliphal guard, and at the death of caliph al-Mu’tamid in 892, the court moved back to Baghdad.

Wall painting, detail of two heads, 9th century, Abbasid caliphate, plaster and pigment, Dar al-Khilafa, Samarra, Iraq (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The fragments of painting shown above come from the Dar al-Khilafa, the largest of the palaces. Its walls were covered with a mixture of figural frescos, stucco reliefs, ceramic tiles, and marble panels, and some of the floors were tiled with glass. These buildings were showcases of all the precious materials that the patrons possessed (some local, others acquired from afar), and all the arts of the skilled workers they could command.

Tile fragments, 9th century, Abbasid caliphate, Millefiori glass, excavated in Samarra, Iraq (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Technologies

The grandeur of Samarra drew on the expertise of craftspeople from across the Islamic world, who had been invited or conscripted to the caliphal workshops. Raqqa-Rafiqa also had industrial areas, especially for the production of glass and ceramics. Artisans around the Abbasid courts developed new methods of production, for instance inventing recipes for glass which used plant-ash instead of natron salt, so that production was no longer restricted to areas with natural deposits of the salt.

Bowl, 9th–10th century, Abbasid caliphate, tin-glazed earthenware with designs painted in cobalt blue, Iraq, 21.5 cm diameter (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Potters experimented with glazes, some of them trying to imitate the precious porcelain vessels from China, which were imported to the caliphate in increasing quantities from the early 9th century, along sea trade routes via Indonesia and India. The Abbasid potters did not have the materials needed to produce porcelain, but succeeded in inventing a white tin-based glaze, as on the bowl shown here. They also developed iridescent luster glazes, a technique that would go on to change ceramic production not only in the Middle East but also in medieval Europe. Although they would have been valued, lusterware plates and bowls were probably not restricted to the very rich, and were made in large quantities for sale in urban markets.

Panel in the “Beveled Style,” 9th–10th centuries, stucco, Samarra, Iraq (Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin; photo: Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Artisans working in various materials in this period developed a new aesthetic of swirling patterns, known today as the beveled style. It was first used in the palaces of Samarra, particularly for stucco wall coverings, and it was also often used for carved wood and stone.

Bowl Decorated in the ‘Beveled Style’, 10th century, earthenware; white slip with polychrome slip decoration under transparent glaze, made in present-day Uzbekistan, Samarqand, 26.7 cm diameter (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The bowl shown above is painted with a two-dimensional variant. It was made in the 10th century in Samarkand, modern Uzbekistan, which was part of the Abbasid caliphate at that time. Samarkand was also the site of the first Islamic mill for paper-making, another technology which (like porcelain) originated in China, and which changed the face of book production as paper replaced parchment and papyrus over the following centuries.

Books

Before the Islamic conquests, large parts of the caliphate belonged to the Byzantine Empire, where Greek was the dominant language, and although the language of government was changed to Arabic in the early 8th century, Greek continued to be widely spoken and written. Many Muslim patrons took an interest in classical literature—continuing a long history of interaction between Arabic and Greco-Roman cultures—and if not bilingual themselves, they commissioned translations. The trend started in the Umayyad period, for example caliph Hisham is said to have enjoyed Arabic translations of tales of Alexander the Great. Under the Abbasids there was an even greater interest in the classics, and works of philosophy, mythology, astronomy, medicine, and others were translated.

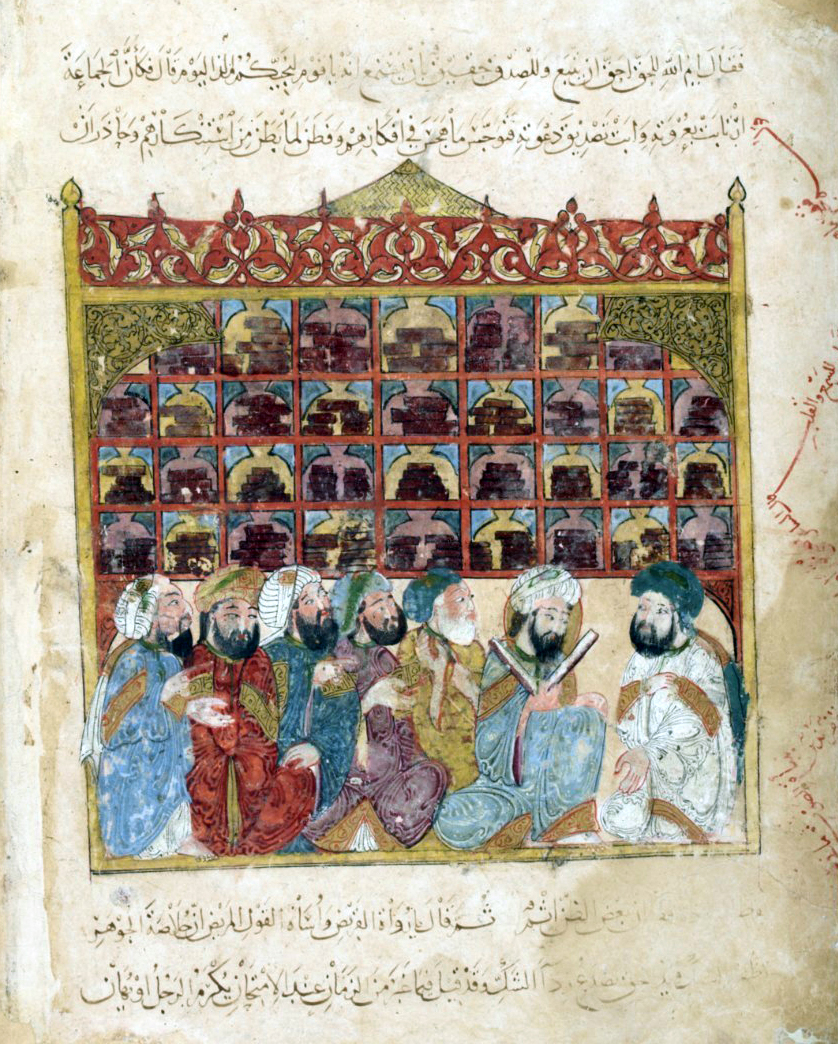

Yahya ibn Mahmoud al-Wasiti, “Scholars in library of the House of Wisdom,” Al-Makamat lil-Hariri, 1237 C.E.(Codex Parisinus Arabus 5847, fol. 5v; Bibliothequè nationale de France)

The library known as the House of Wisdom in Baghdad (bayt al-hikmah, destroyed during the Mongol siege in 1258) was a major center for this project, and there scholars from a range of cultural and religious backgrounds produced Arabic editions of Syriac, Aramiac, Hebrew, Pahlavi, and Sanskrit texts. The image above shows an idealized version of the library, with scholars engaged in debate below—their hand gestures show that it is a lively discussion—and the collected works of the institution piled up above them.

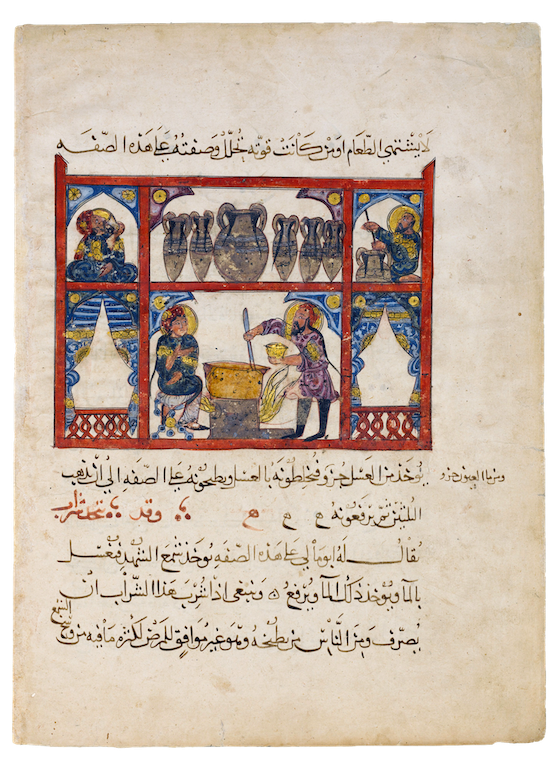

The illustration shows a doctor making a medicine from honey, with a patient drinking the result at top-left. “Preparing Medicine from Honey”, from a Dispersed Manuscript of an Arabic Translation of De Materia Medica of Dioscorides, dated A.H. 621/1224 C.E., ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 31.4 x 22.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The image here comes from one of the many works translated in medieval Baghdad. It is an Arabic version of a 1st-century C.E. Greek medical work by Dioscorides, now generally known by its Latin name, De Materia Medica. The translation was first made in the 9th century by two Christian scholars, Stephanos ibn Basilos and Hunayn ibn Ishaq, and this specific manuscript was made in the 13th century, also in Baghdad. The illustration above shows a doctor making a medicine from honey, with a patient drinking the resulting medicine at top-left.

Abbasid scholarship was not limited to copying earlier works; for instance astronomers working for caliph al-Ma’mun in the 830s calculated the circumference of the earth, improving on ancient measurements, and established accurate figures for the phenomenon known as the precession of the equinoxes.

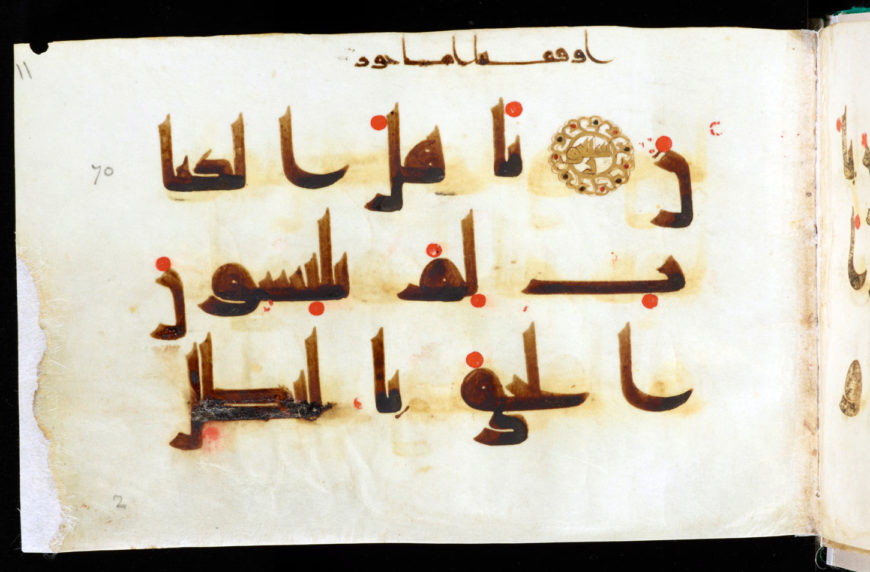

Amajur Qur’an, before 9th century C.E. (264 AH), pigment and ink on parchment, 12.3 x 18.9 cm (MS Add.1116, Cambridge University Library)

There were also developments in the format of Qur’anic manuscripts. Great emphasis was placed on the beautiful proportions of calligraphy, and a new form of script became popular; it is sometimes called Kufic, after the city of Kufa, but it was widely used across the Abbasid caliphate. Symbols for marking verses or groups of verses became more common during the 9th and 10th centuries, usually circular designs ornamented with loops, swirls or petals, and in more expensive manuscripts they were illuminated in gold, as above.

The Qur’an shown above was made for Amajur, Abbasid governor of Damascus in the 870s, and he donated it to a mosque in the city of Tyre in Lebanon. The script does not include all the diacritical marks used in written Arabic today, and along with the elegantly stylized letter shapes and the gilded verse marker, the effect is to make this a work of visual art just as much as a piece of text.

Artistic legacies

The artistic legacies of the Abbasid caliphate are varied. Some of the monuments described in this essay were short lived; impressive as they were, the palaces of Samarra barely lasted for two generations. But many visual and technological innovations of the period, from lusterware ceramics to “Kufic” script to the engagement with classical scientific literature, continued to be significant components of Islamic culture—and influences on surrounding cultures—for centuries to come.