Related works of art

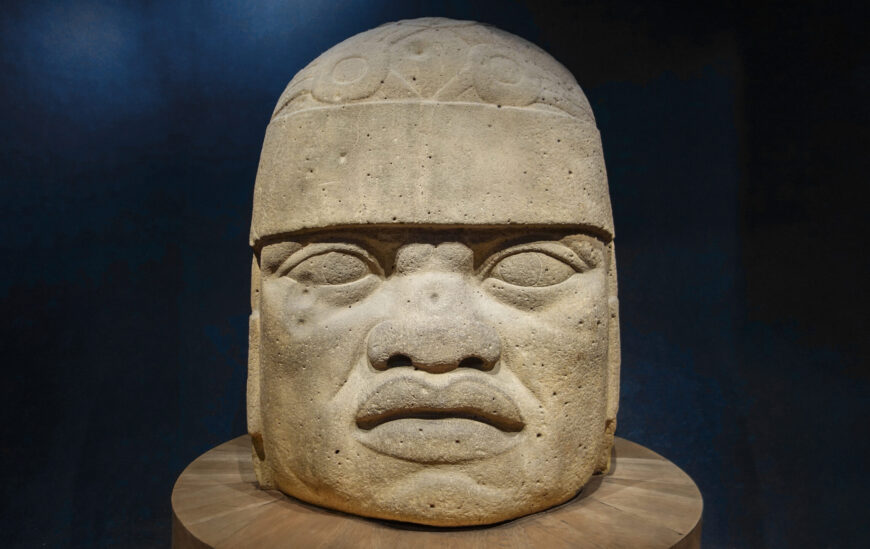

In the Ancient Mediterranean

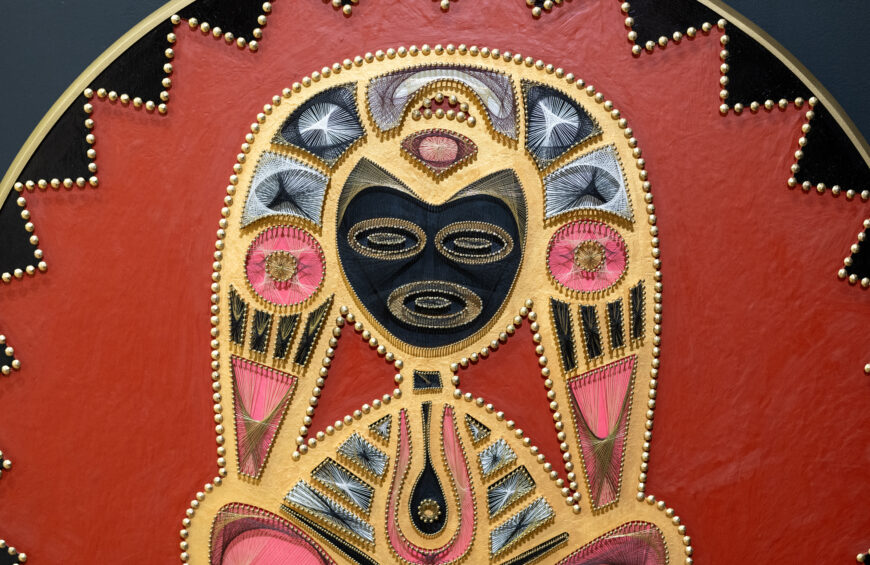

Masks

Active in c. 5000 B.C.E.–350 C.E. around the World

In North Africa

Isamu Noguchi, Gregory (Effigy)

originally designed in slate in 1945, cast in bronze in 1964

United States

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!