From the earliest of history to the modern period, works of art and architecture have been designed to convey the power of rulers. While the following examples will often rely on a shared visual vocabulary to suggest power — including expensive materials, large size, and hieratic scale — each example draws on its own culture for the most basic idea of what it means to be powerful, and each will express these ideas in its own fashion. In one culture, violence might be the hallmark of power, whereas in another support from the masses might be more important.

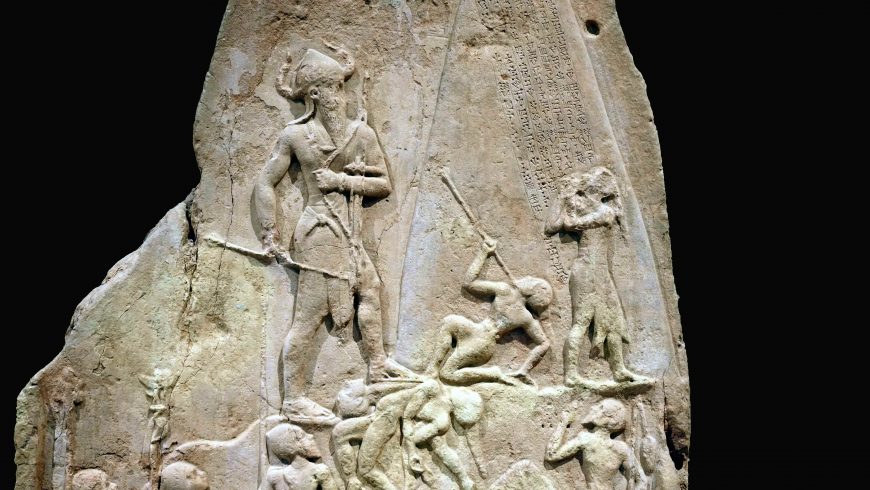

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, 2254-2218 B.C.E., pink limestone, Akkadian (Musée du Louvre, Paris) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Naram-Sin guided to victory by the gods

The earliest written records to survive come from the Ancient Near East — from a series of civilizations that flourished in what are now Iran and Iraq. One of the period’s earliest empires — the Akkadian empire — was established by Naram-Sin, who inherited the throne and ruled until 2218 B.C.E.

Naram-Sin’s grandfather, Sargon I, was purportedly the illegitimate son of a high priestess and sent down the Euphrates river in a basket (much like Moses — this is a common trope in ancient myth) before being rescued and raised by a gardener. He founded a city and established dominance in the region through military success. Naram-Sin continued in his grandfather’s path, gaining power through force, and extending Akkad’s range of control and influence. In order to maintain this control, though, Naram-Sin had to frequently crush rebellions.

The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin commemorates his defeat of the Lullubi. The stele — an upright stone marker — makes a strong visual statement about the power of Naram-Sin. The composition is arranged in loose registers, angling up from the lower left to the upper right. The main figure is easy to spot, here: Naram-Sin is represented in hieratic scale, so that he towers over all the figures around him. He is the highest figure on this large stele (which is over six and a half feet tall). He is also surrounded by more negative space than the other figures, who in contrast are crowded together in a jumble.

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin, 2254-2218 B.C.E., pink limestone, Akkadian (Musée du Louvre, Paris) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The space around the king is empty, so that he stands out clearly. This, though, merely draws our attention to him. His power is shown through his actions and the symbols on and around him.

Just in front of him, a figure clutches a spear that Naram-Sin has thrust through his neck. The king carries other spears, a bow and arrows, and a battle-axe, as if a one-man army. Unlike Qin Shi Huangdi, who demonstrated his military power through images of his thousands of soldiers, Naram-Sin had himself presented as the most powerful member of his army, displaying a god-like ability to slaughter his enemies.

In addition to the dying figure bending backward before him, there are two more corpses splayed out in a heap beneath his left foot. Another falls vertically down the stele, breaking through the registers. Additional figures raise their hands to plead for their lives even as they flee — note how the torso and face of the pleading figure in front of Naram-Sin is facing the conquering king, while his feet clearly point in the opposite direction.

The massive and aggressive figure of Naram-Sin is capped with a horned helmet, an attribute that prior to this image was only depicted on gods and that therefore suggests that he has been deified (considered as a god). Inscriptions tell us that he was known by the title “god of Akkad,”[1] and here the power of this mighty god-king seems infinite. As he ascends the mountain, he moves closer to the three suns (one now mostly lost) at the apex of the image. These are symbols of the gods of the Akkadians, guiding Naram-Sin to victory and suggesting his own divinity.

Great Pyramids of Giza

Representations of power in the ancient world, though, reached their peak with the art and architecture of the Egyptian kings, or pharaohs, particularly in the Great Pyramids of Giza. Built by the pharaohs Menkaure, Khafre and Khufu, they remain the most monumental works of architecture in the world — no more massive buildings have ever been built. These are the only surviving works of the so-called Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, a group of marvels described in Ancient Greece to acknowledge what were considered to be the most remarkable works of art and architecture known at the time, and their survival is due to their massive style of construction.

Great Pyramids of Giza,: Khufu (c.2600-2550 B.C.E.), Khafre ( c.2575-2525 B.C.E.) and Menkaure (c.2525-2475 B.CE.) (photo: Tim Kelley, CC BY-ND 2.0)

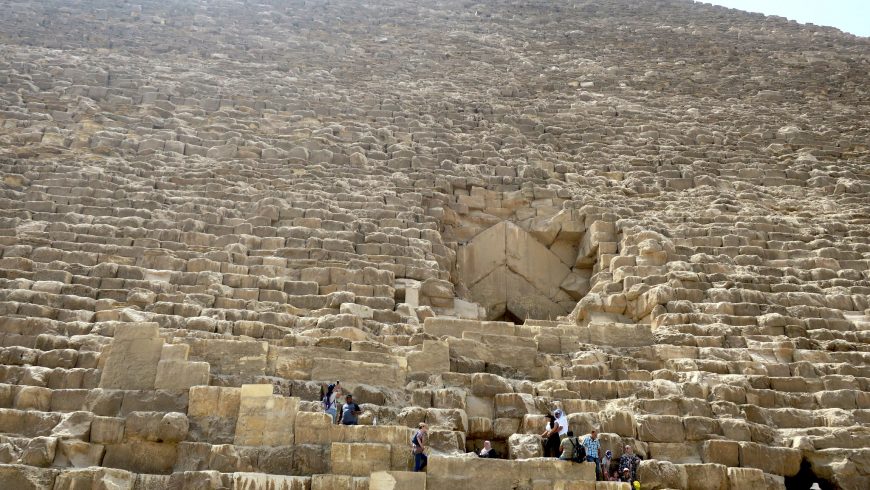

As the focal points within a necropolis they dominate the landscape. The Pyramid of Khufu is the oldest and largest. It was originally nearly 500 feet tall at the apex, and the base is approximately 750 feet long on each side, covering thirteen acres. These numbers are so large that they are hard to grasp, but a detail photograph showing the size of the individual blocks helps convey the pyramid’s size.

Entrance to the Pyramid of Khufu, Giza (photo: Terrazzo, CC BY 2.0)

The size of the pyramids is not all that conveys the power of their patrons; the style also impacts this impression. They are not only large, and radially symmetrical, but also almost completely unadorned. Originally, the surfaces were covered with smooth blocks that would have given them perfectly straight sides, rather than the stepped sides they now have. They would therefore have presented the viewer with a structure so unified that each might even seem to be a single object on the grandest possible scale. While Qin Shi Huangdi was also buried beneath a mound, his low hill was carefully concealed from view beneath grass and trees. In strong contrast, these works are literally man-made mountains, rising over the flat planes of Giza, dominating the landscape and dwarfing all surrounding structures. As such, they were very clear statements of the power of the god-kings buried within them.

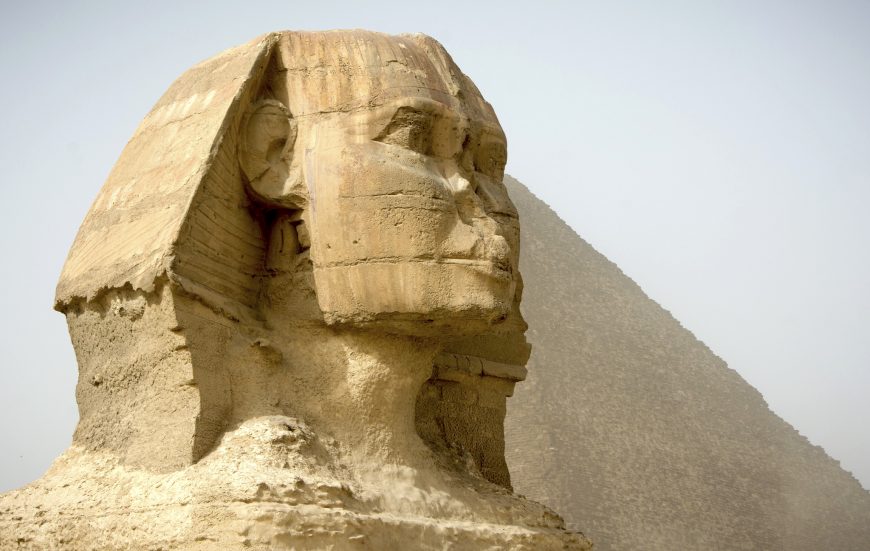

Great Sphinx, Giza, Egypt, c. 2520 – 2494 B.C.E. (photo: Alexander C. Kafka, CC BY-ND 2.0)

The Great Sphinx

The pharaohs commissioned numerous images of themselves, many of which were created for spaces inside and around the pyramids. Perhaps most well-known of these is the Great Sphinx, guarding the entrance to the Pyramid of Khafre. It sits at the entrance to the long causeway that leads to a funerary temple and then to the pyramid. This figure, 65 feet tall and almost 190 feet in length, has the body of a lion but is capped by an image of the head of the pharaoh, wearing the royal cobra headdress.

The Sphinx sits upright and alert, in formal symmetry. The figure was not assembled out of blocks, as the pyramids were, but rather, was carved out of “living rock” — stone still connected to the earth — though there are some additions to this. The image suggests the pharaoh’s tremendous power, since it is not only colossal but also merges him with the most respected predator of Africa: the lion. The Sphinx has unusually large eyes, and this emphasis serves to suggest that this powerful creature is a most watchful guardian. Qin Shi Huangdi entrusted his protection in the afterlife to his vigilant soldiers. Khafre, on the other hand, seems to guard himself.

Great Sphinx, Giza, Egypt, c. 2520 – 2494 B.C.E. (photo: Morgan Schmorgan, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Rattle Staff: Oba Akenzua I Standing on an Elephant (Ukhurhe),1725–50, Edo, Nigeria, bronze, copper and iron, 161.3 x 4.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A staff for a Benin king

These large, watchful eyes can be found in thousands of images of gods and rulers, giving the viewer the sense that these absent individuals are nonetheless scrutinizing us. The portrait style common in the art of the Benin kingdom of the eighteenth century is highly abstract, with features of importance enlarged for emphasis. In this way, proportion is manipulated to draw the viewer’s attention to key elements, like the eyes.

Here, we see a rattle staff, called an ukhurhe, made for a powerful oba, or king. Oba Akenzua I ruled Benin in the early eighteenth century. The oba’s staff is capped with an image of himself, holding a simpler ukhurhe. This staff was probably used as a public political statement of power, unlike more traditional ukhurhe, which were carved in wood.

Akenzua’s great, wide-set eyes would have been directed both at his ancestors — the source of his power and authority — and at his subjects. The staff, over five feet tall, has a hollow segment near the top, with narrow slits along its length, which rattles when shaken during prayers. This example is brass, which means it was a high-status item. As with Qin Shi Huangdi, there is a balance in this work between worldly and spiritual power. The oba is shown dressed for a ceremony in elaborate royal garb, much of which would be made of valuable materials. As shown on the image on the ukhurhe, his headdress, the rings around his neck, and the panels on his chest would be made of coral and his armbands would be of ivory. This costly costume would declare to the viewer that the figure is no ordinary man. In a photograph of his descendant, Akenzua II (who ruled from 1933-1978), we can see an oba in a similar costume, giving a sense of how Akenzua I would have appeared in life.

The figure’s importance is declared by his placement at the top of this luxury item, and his symmetry gives him a stable, solid, dignified appearance. His enlarged eyes declare his watchful nature. While the image of Akenzua itself is small — only about six inches in height — hieratic scale is used to demonstrate his importance: he stands on the back of an elephant, an animal associated with rulership, and is more than twice its height. The elephant’s trunk ends in a human hand. This may be a reference to Iyase n’Ode, believed to be able to transform into an elephant, who led a rebellion against Akenzua.

Placing Akenzua atop the elephant makes a strong statement about Iyase n’Ode’s defeat and the oba’s triumph. The elephant is also hemmed in on both sides by leopards, symbols of the oba’s power.[2] The elaborate nature of the depiction of the oba is the result of the centrality of the king to the art of Benin.

Detail, Rattle Staff: Oba Akenzua I Standing on an Elephant (Ukhurhe),1725–50, Edo, Nigeria, bronze, copper and iron, 161.3 x 4.8 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The oba was both the main subject of the art, and also its most important patron. This forceful depiction of Akenzua’s power is fitting, as he was the ruler of a kingdom that had ruled the region since the fifteenth century. In this case, therefore, the iconography — the series of signs and symbols in the art of a culture — works with the principles of composition to create a strong statement of the oba’s authority.

Napoleon on his throne

We again confront the direct gaze of the ruler when we stand before Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres’s large oil painting Napoleon on his Imperial Throne. This is a work that tries very hard to capture some of the majesty of earlier images of rulers through composition, technique and symbolism.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Napoleon on his Imperial Throne, 1806, oil on canvas, 260 x 163 cm (Musée de l’Armée, Paris)

The recently crowned emperor is shown centered in a highly symmetrical composition, seated on a gilded throne that frames his head like a halo, suggesting his divinity. The semi-circle of the white ermine fur cape draped over his shoulders visually completes the semi-circle of the back of the throne. The circles are carefully aligned to seem to be continuations of one another, thereby doubly framing Napoleon’s head.

Staff with an image of Charlemagne (detail), Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Napoleon on his Imperial Throne, 1806, oil on canvas, 260 x 163 cm (Musée de l’Armée, Paris)

Napoleon’s clothing and accessories could not be more sumptuous: fur, velvet in red — the color that has symbolized imperial power since Ancient Rome — and gold. The staff he holds in his right hand is topped with an image of Charlemagne, the revered medieval French king who was the first to be crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. This great predecessor (Charlemagne is French for “Charles the Great”) is posed quite similarly to Napoleon, suggesting a strong connection between these two French rulers, each of whom was the first in his era to be declared emperor.

Like the image of Akenzua on his ukhurhe, holding an ukhurhe, here the small image of Charlemagne atop Napoleon’s staff also holds in his right hand a staff — this one capped with the fleur-de-lis (the symbol of the French monarchy).

The staff in Napoleon’s left hand was believed at the time to have belonged to Charlemagne, and the sword he bears is that of his precursor, as well. As Qin Shi Huangdi used ancient burial practices to connect himself to the tradition of his ancestors, Napoleon used these medieval treasures to connect himself with the past of France. He also bears the golden laurel wreath crown of the Roman emperors, and the arms of his golden throne and the carpet at his feet both contain the image of the Roman eagle.

Ingres paints all of these elements with extreme precision, so that we can see each gem and jewel, and with such attention to the texture of the materials that is seems almost as if we could feel them beneath our fingers, as we look at the image. This lavish portrait was an attempt by Napoleon to demonstrate his great power, and also to argue that, although he had created a new empire, he was continuing the tradition of Charlemagne, and of the great Roman emperors of antiquity.

A Joseon throne

Throne Hall, Gyeongbokgung Palace, main royal palace of Joseon dynasty, in Seoul, South Korea, 1395 (photo: Terry Feuerborn, CC BY-NC 2.0)

In the portrait of Napoleon, we see a representation of a fairly lavish throne, but it pales in comparison to the actual Throne Room of Gyeongbokgung Palace in Seoul, South Korea. This was the primary palace of the Joseon Dynasty, originally completed in 1395 CE, but burned down in 1592 during the Japanese invasion of Korea, and largely rebuilt in the mid-nineteenth century.

Unlike roughly contemporary cities in China and Japan, Korean cities and palace compounds were not traditionally symmetrically organized. Instead, they followed natural features in an effort to achieve pungsu (feng shui). This makes the layout of the building and throne, itself, all the more striking. Geunjeongjeon Hall (“Hall of Diligent Rule”[3]) is a large, rigidly symmetrical structure, based on Chinese models, with two tiers of roofs that curve gently upward at the corners. It is set at the top of a platform with three tiers, requiring that the visitor climb more than a dozen steps before entering the hall.

Throne Hall, Gyeongbokgung Palace, main royal palace of Joseon dynasty, in Seoul, South Korea, 1395 (photo: Blmtduddl, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The building contains a single cavernous room, centered on the throne, which sits again atop a platform, elevating the king within this elevated palace. Behind the throne are wooden screens, and then a painted backdrop with five mountains, the sun, and moon, all exclusive symbols of the king. A canopy hangs over the throne, with two dragons, also symbols of the king, on its inside, only visible to the king himself, while he is seated on his throne. The king, seated on a throne on a platform, in a palace on a platform, would appear superior to all those beneath him.

Ironically, the Joseon Dynasty, following neo-Confucian ideas (based on the Confucian writings banned and burned by Qin Shi Huangdi), believed that the king’s power and authority came from his fairness, and so, compared to other royal palaces of the region, Gyeongbokgung is relatively simple. Still, it is clear that despite rhetoric about equality, the king was no ordinary citizen. Like Napoleon on his throne, Khafre in his pyramid and as the giant sphinx, Naram-Sin atop his mountain, and Qin Shi Huangdi in his tomb, the Joseon king relied on art and architecture to convey his great power and to elevate him, quite literally, above his people.

It is important to note that the use of art to convey the power of rulers is not an ancient phenomenon. It continues in the modern world, though often on a more modest scale than in Ancient Egypt and China.

Appropriating symbols of power

U.S. soldiers cover the face of a statue of Saddam Hussein with an American flag before toppling the statue in downtown in Baghdad, Iraq. (LAURENT REBOURS/AP)

For a more recent example, we turn to a statue of Saddam Hussein, former dictator of Iraq, which once stood in Firdos Square, Baghdad. This statue was one of thousands of images of Hussein, and was produced (as many of the images in this chapter were), at the orders of a powerful patron. It was a monumental bronze sculpture, set on a tall pedestal. Hussein appeared in a business suit, with a hand raised as if he were greeting a large crowd of supporters.

This image became famous throughout the world just a month after the United States-led invasion of Iraq began, and serves as a reminder that symbols of power can be used against those they are created to glorify. On April 9, 2003, a battalion of US marines secured central Baghdad and arrived in Firdos Square, in front of the Palestine Hotel, where over two hundred reporters were staying. The presence of so many reporters meant that, as the Marines assisted a group of Iraqis in toppling the statue, the event was broadcast live throughout the world.

The statue celebrated and declared Hussein’s power, but in the aftermath of the invasion, its toppling became a more complicated symbol of his fall from power. According to the most detailed account available, a US marine instigated the small crowd of Iraqis, and provided them a sledgehammer and rope.[4] When it was clear this was not sufficient to pull down the statue, the marines sought and received authorization to use a large tow truck to topple it. While a corporal was hooking up a chain to the statue’s head, he was handed a U.S. flag, which the wind then whipped across the face of the image of Hussein. He spread it more fully across the face and, seconds later, took it down.

This brief moment was photographed, filmed, and broadcast, becoming a central image of the invasion. Had the Iraqis pulled down the statue without the help of the truck, images would have appeared to show a spontaneous act by a joyously liberated populace (though this would have been false). Had the statue been toppled without the flag, the images would appear to show cooperation between the Iraqi people and the US military. The ultimate image (though it was not really such) looked like a deliberate statement by a conquering occupier. In this way, a work of propaganda for a powerful, autocratic ruler became a symbol of his defeat at the hands of an invading military.

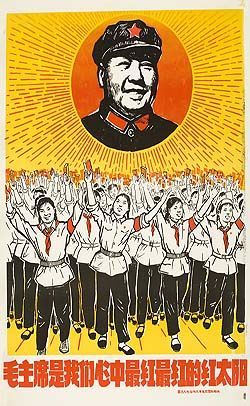

Lu Xun Art College Artists, Chairman Mao is the reddest red sun in our hearts, 1967 poster (Westminster Chinese Poster Collection)

Art for the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

In 1966, the Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong began the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. The movement was intended to address growing class inequality. When the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, one of its founders’ goals was to decrease the economic divide between the rich and poor, but in the following decades, as Mao saw it, the government had moved away from this principle.

In the propaganda poster Chairman Mao is the reddest red sun in our hearts, we see Chairman Mao in the center of the red sun, smiling and radiant. Beneath him is an army of loyal supporters. These figures stand in for the 20 million youths who joined the Red Guard in order to root out “class enemies.”[5] They hold aloft copies of Mao’s Little Red Book, which contains a list of sayings to encourage the masses to fight against class oppression. For example:

In class society, everyone lives as a member of a particular class, and every kind of thinking, without exception, is stamped with the brand of a class. It is up to us to organize the people. As for the reactionaries in China, it is up to us to organize the people to overthrow them. Everything reactionary is the same; if you do not hit it, it will not fall. This is also like sweeping the floor; as a rule, where the broom does not reach, the dust will not vanish of itself.Mao Zedong, LITTLE RED BOOK, 1964

Like most propaganda, it is not intended to be subtle; it is supposed to make a clear and dramatic point. The placement of Mao, centered at the top of the image, declares his importance, which is reinforced by the seemingly infinite crowd beneath him. Like the soldiers of Qin Shi Huangdi, they are nearly identical in dress, conveying their common purpose, but are slightly differentiated to give a sense of the individuality of the volunteers, united behind Mao.

The horizon line is located behind the figures, approximately at the eye-level of the young women in the front row. This effectively places the viewer within the crowd, as if we are marching along with them. It also has the effect, as the figures recede into the distance, of dissolving the crowd into a sea of hands, all holding up the Little Red Book toward the giant image of Mao. As the raised hands of the figures recede into the distance, the amount of detail diminishes, so the books they hold lose their black outlines. The effect of this is to make them seem as if they are being formed out of the rays that emanate from the red circle around Mao. Like a sun god, Mao shines his message down onto his followers, who receive it with great joy.

The woodcut technique used here — in which a series of blocks is carved to create the image, covered with ink, and then pressed to the page — has become a staple of political imagery since the 1960s. Is it an inexpensive way of producing a large number of images. Unlike the impressive and expensive works discussed above, this poster achieved its effect through large-scale distribution. The high contrast and large, flat panels of color common in woodcuts make this technique well suited to carrying clear messages to the masses.

The following section will consider works that resist the sorts of power dynamics presented by the works discussed so far, many of which rely on similar visual techniques, but were created by artists working to achieve a greater measure of equality. Mao is an interesting figure with which to make the transition, since he was both a revolutionary leader of a populist movement and, later, an autocratic and repressive ruler. In this image, he is shown fighting against entrenched powers, but also as a clear source of power as well.