Orientalism: What is it, and how has it affected our understanding of Islamic art?

Read Now >Chapter 27

Framing Islamic art

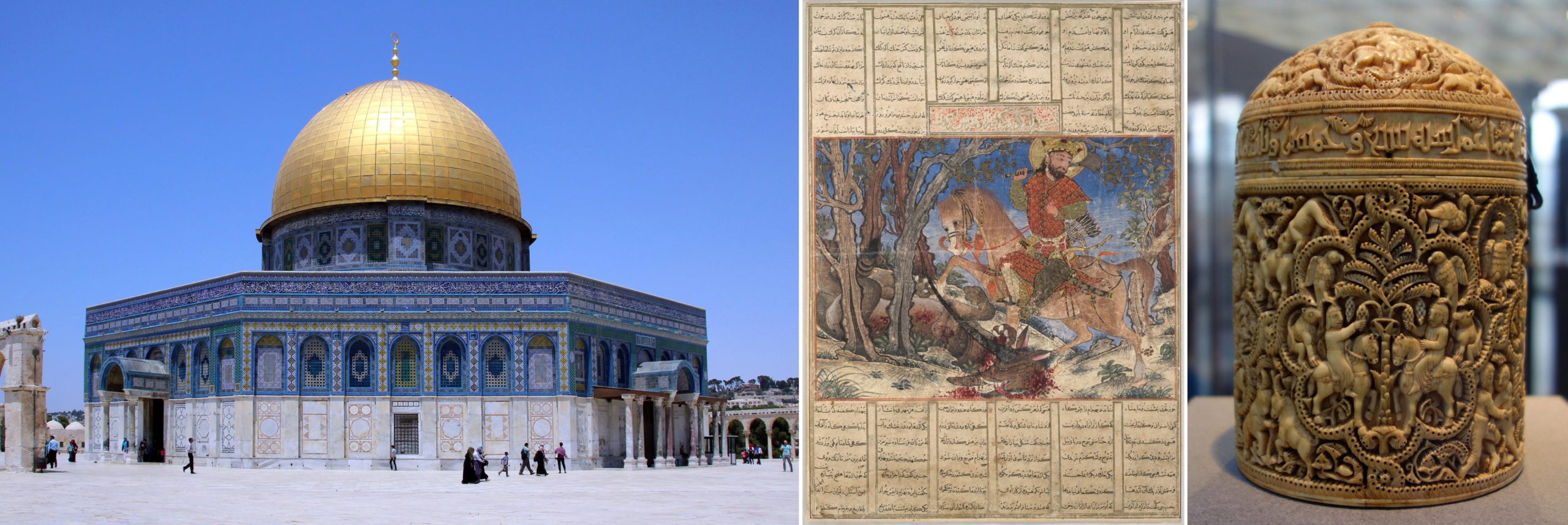

Left: The Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Sakhra), Umayyad, stone masonry, wooden roof, decorated with glazed ceramic tile, mosaics, and gilt aluminum and bronze dome, 691–92, with multiple renovations, patron the Caliph Abd al-Malik, Jerusalem (photo: Gary Lee Todd, CC0 1.0); center: Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf), from the Great Mongol Shahnama, c. 1330–40, Iran, ink, colors, gold, and silver on paper, folio 41.5 x 30 cm (Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum); right: Pyxis of al-Mughira, possibly from Madinat al-Zahra, AH 357/ 968 C.E., carved ivory with traces of jade, 16 x 11.8 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Flipping through the Islamic art chapters in most global art history survey textbooks, you’ll immediately see a selection of monumental architecture, colorful miniature paintings, and ornamented portable objects. Parts of West Asia, North Africa, South Asia, and Iberia (today, Spain and Portugal) will be well represented. But if you take a small step back, you may also notice how nearly 1500 years of artistic production is squeezed into less than a tenth of the book!

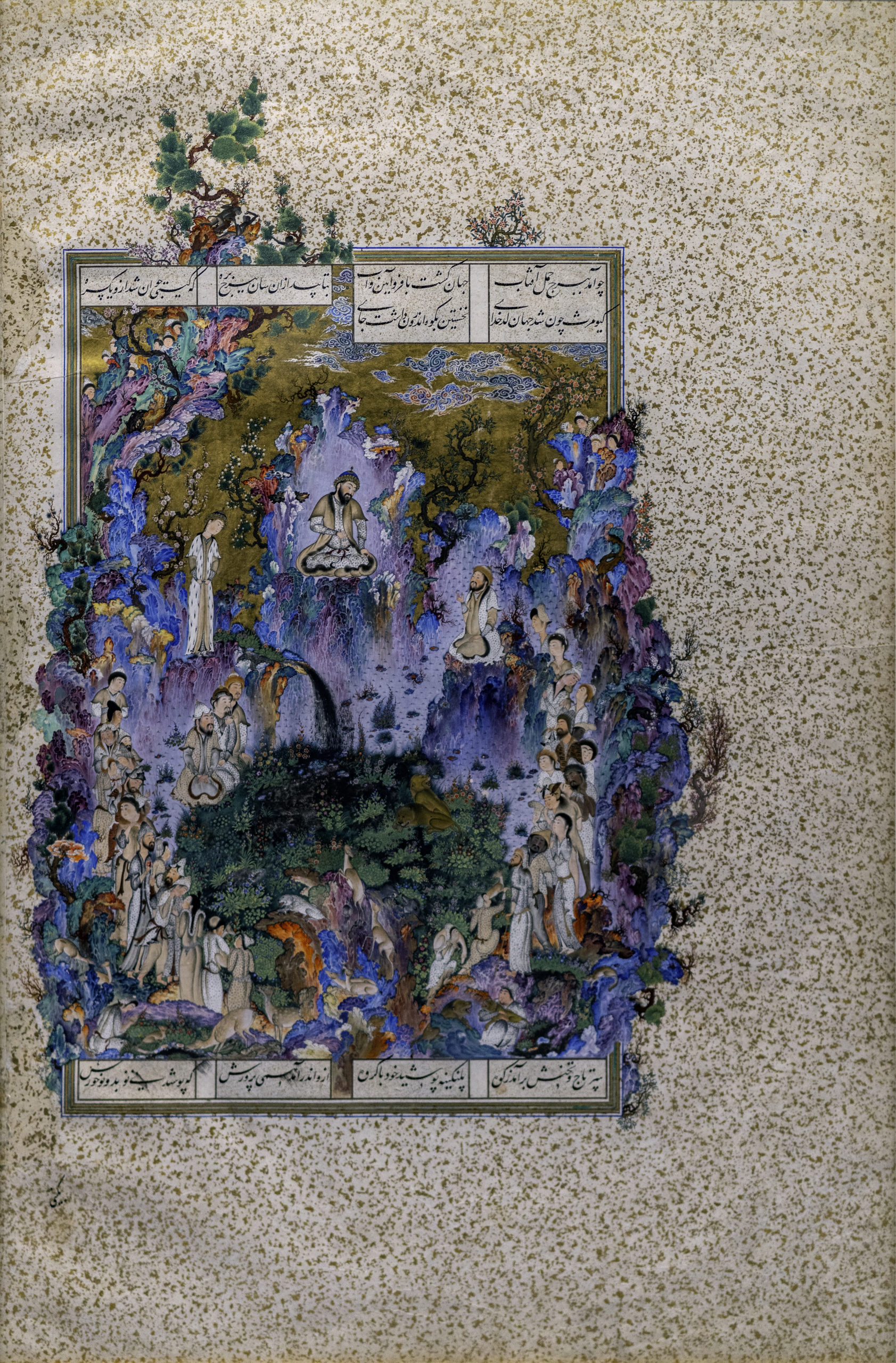

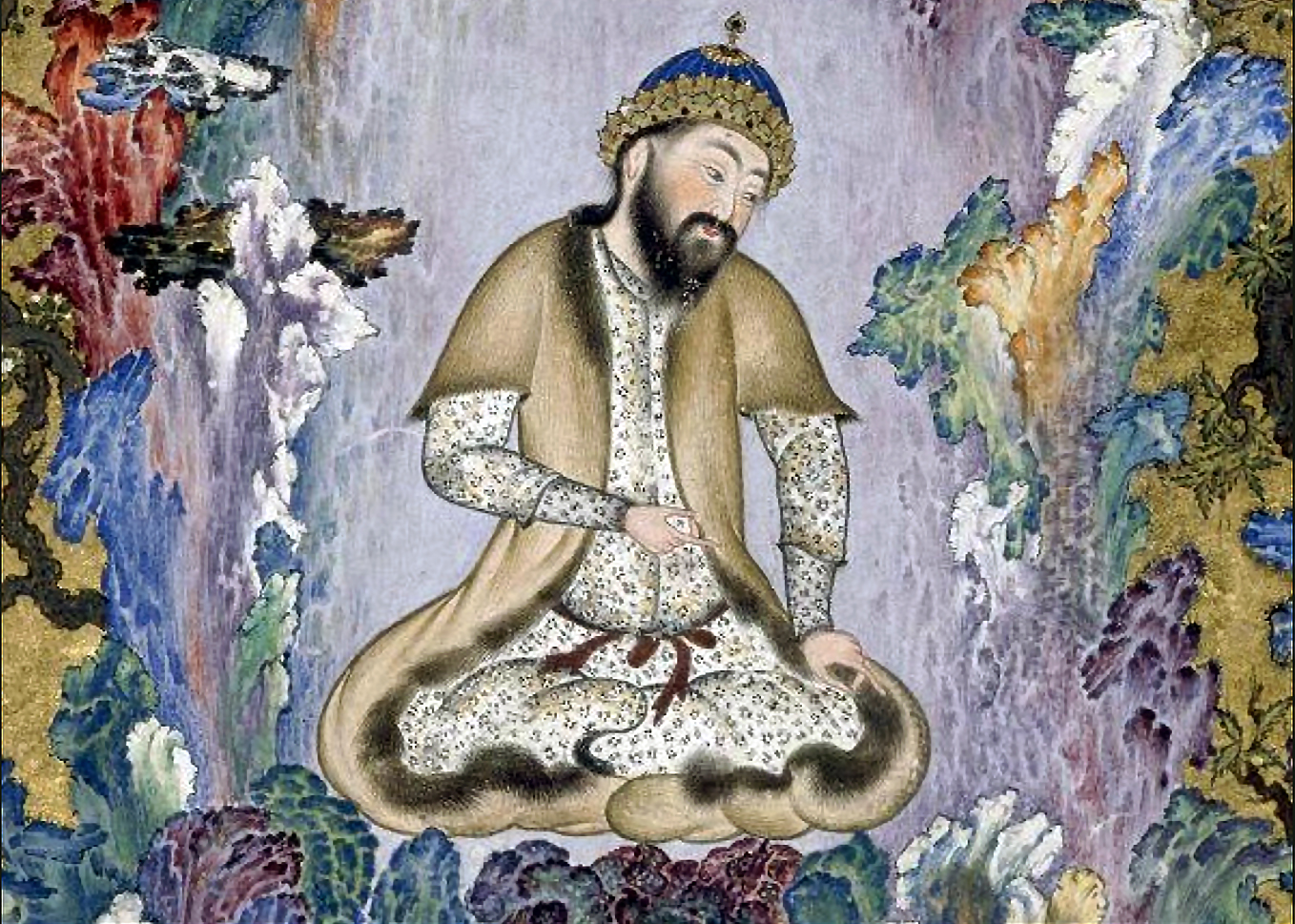

Sultan Muhammad, “The Lord of the World” shown as part of “The Court of Gayumars,” 47 x 32 cm, opaque watercolor, ink, gold, silver on paper, folio 20v, Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp I (Safavid), Tabriz, Iran (Aga Khan Museum, Toronto; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Slenderly sandwiched somewhere between the late antique and medieval periods, Islamic art is frequently presented as a tangential aside in the otherwise relatively seamless development of Western visual traditions. Even in Islamic art survey texts, the story usually comes to a screeching halt around 1700 C.E., with any creations after included almost as an addendum, misleadingly signaling a rift rather than continued evolution. [1] This chapter will steer you through a slightly different journey by intertwining a thematic look at Islamic art while engaging with the field’s own history and idiosyncrasies.

Though a relatively young discipline, the origins of Islamic art history are intimately entangled with the blossoming of art history itself in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Most early scholars arrived from disparate fields such as Classical archaeology, Byzantine numismatics, Arabic or Persian philology, and others. Embedded within Orientalism interests and colonial pursuits at first, the discipline of Islamic art history emerged as a separate area of inquiry from the intellectual networks of Europe, West Asia, North Africa, and North America during the late 19th to mid-20th centuries. Through these networks, scholars laid the foundations for what has now become a thriving, ever-expanding, and inherently interdisciplinary field of knowledge.

Floor painting (fresco) of Ge or Gaia, from Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi, Syria, now in the National Museum in Damascus, 727 (photo: Daniel Waugh)

You may wonder why this background matters. For one, it helps us understand the tendencies of early scholarship to define and circumscribe Islamic visual culture along the lines of Western art, with beginning and ending points often bound by the collapse of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance awakening of Europe. While such pioneering studies remain valuable pillars of the discipline, they inadvertently pigeonhole Islamic visual production as a stunning feature of the Middle Ages, and when viewed from a purely Western vantage point, as a tradition lagging behind North Atlantic cultures.

The Great Mosque of Central Java (Masjid Agung Jawa Tengah), 2002–06, Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia (photo: Christ Woodrich, CC BY-SA 3.0)

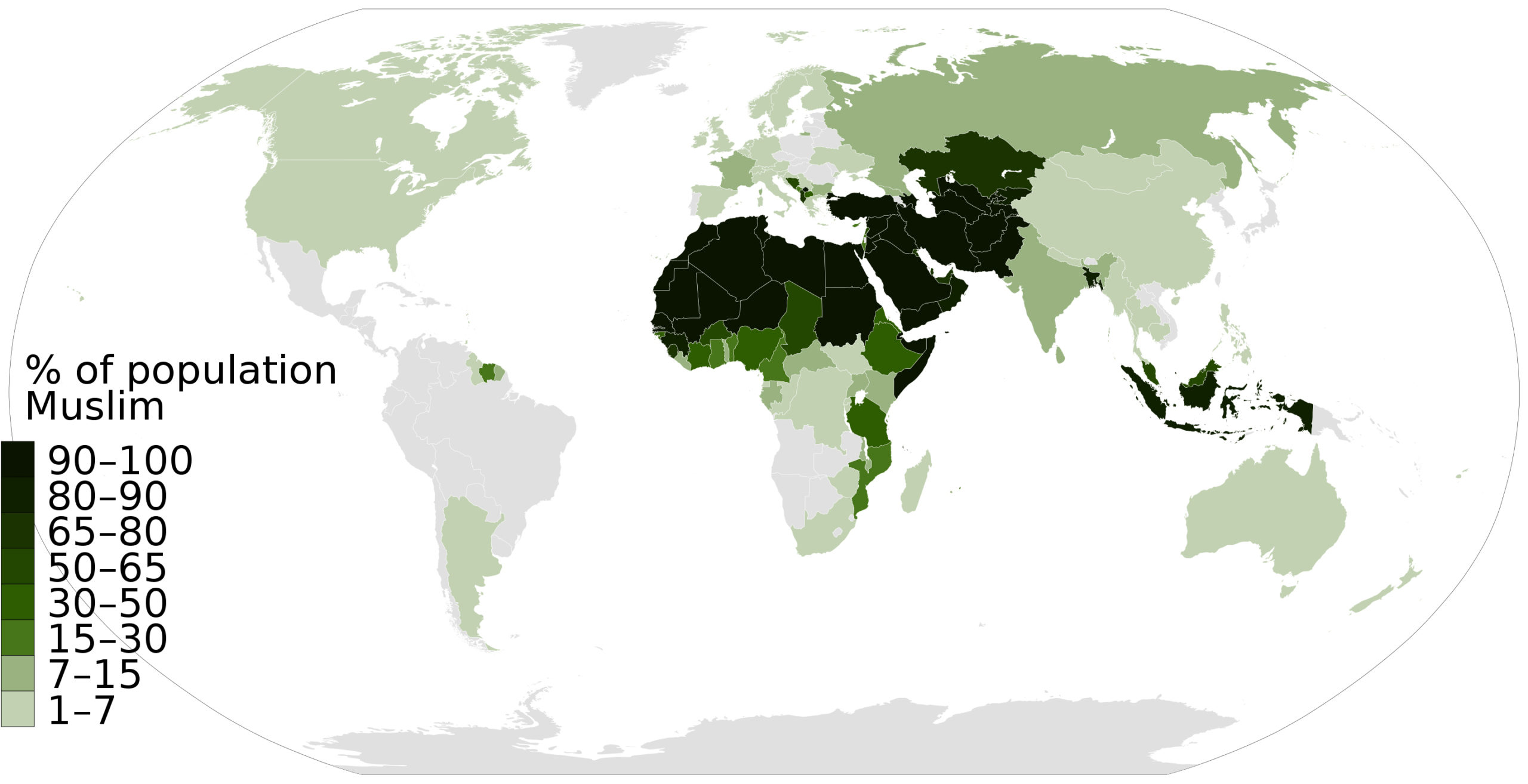

Additionally, the legacy of this early focus on central Islamic lands (Arabia, Mesopotamia, Red Sea, and Mediterranean shores, etc.) skewed public understanding of the vast geographical expanse across which Muslim cultures have flourished for centuries.

World Muslim population by percentage (Pew Research Center, 2014)

Things are rapidly changing however, and in recent years exciting new scholarship has shed much needed light on previously understudied time periods (such as the nineteenth century) and regions (such as Southeast Asia).

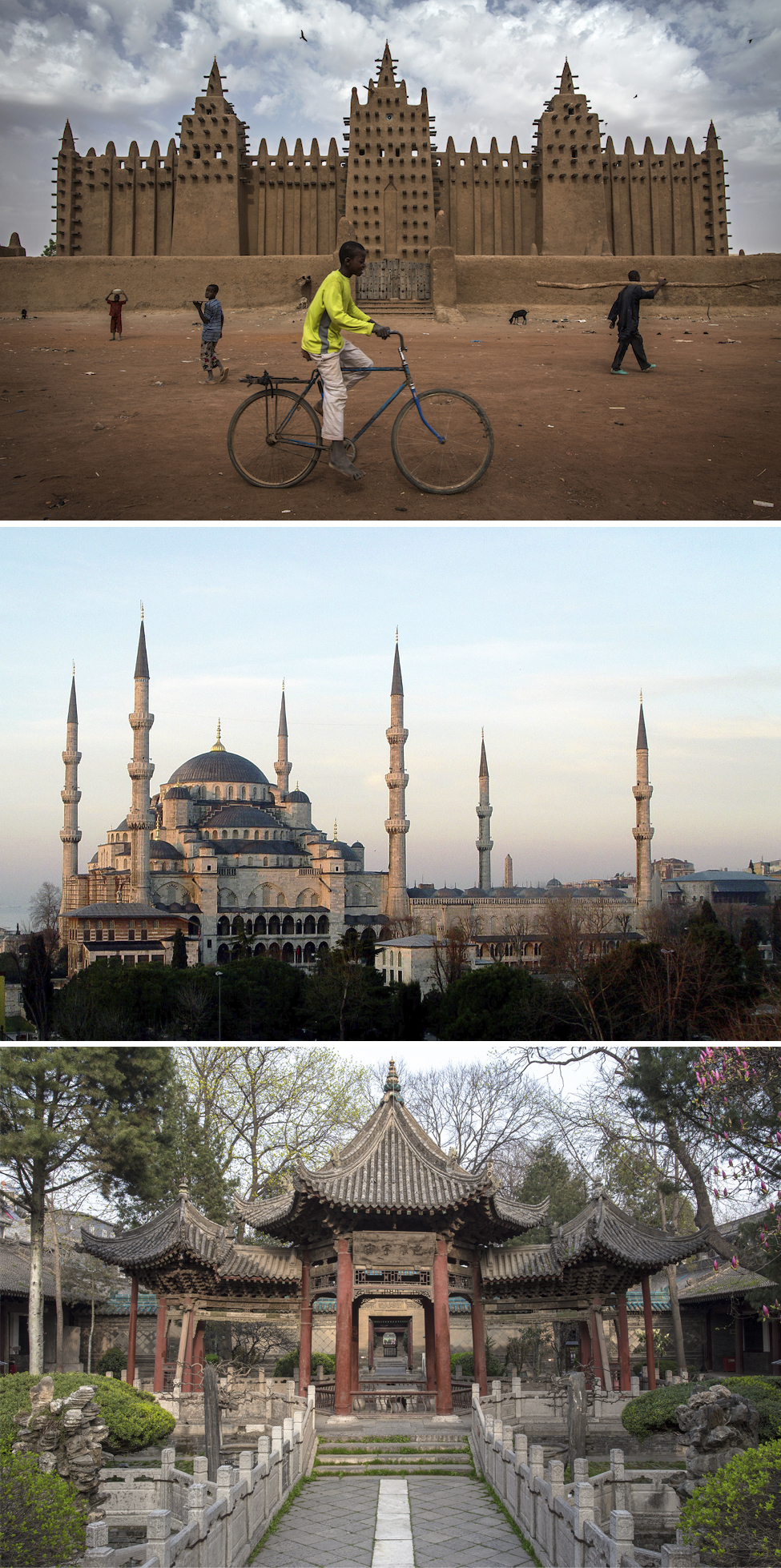

Top: A view of the Great Mosque of Djenné, designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988 along with the old town of Djenné, in the central region of Mali; center: Sedefkâr Mehmed Ağa, the Blue Mosque (Sultan Ahmed Mosque), completed in 1617 (photo: Oberazzi, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); bottom: View of the Great Mosque of Xi’an, Shaanxi, China (photo: Alex Berger, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Lastly, even though Islamic art comprises an astonishing diversity of cultures and visual styles, outside of the scholarly sphere it is often understood as being rather homogenous. For example, the Djenne Mosque (Mali), the Blue Mosque of Istanbul (Türkiye), and the Great Mosque of Xi’an (China), despite being visually unrelated, all function as Muslim sites of congregational prayer. Their distinct styles are a function of local cultural influences rather than a universal Muslim aesthetic.

Read an essay about Orientalism

/1 Completed

An overview of Islamic Art and the Faith of Islam

Let’s begin with a brief overview of Islamic art to get you acquainted. The two essays below introduce major themes, geographic breadth, and widely used chronologies.

Read essays that introduce Islamic art

/2 Completed

As you look through those topics, you may have questions about Islam itself. To familiarize yourself with the faith, read through the following short essays about its rich history, main principles, and the holy pilgrimage to Mecca.

Read essays about Islam

Introduction to Islam: Islam, one the world’s main monotheistic faiths, was founded in the 7th century by Muhammad, a merchant from Mecca.

Read Now >

The Five Pillars of Islam: In their religious practice, Muslims follow five fundamental tenets.

Read Now >

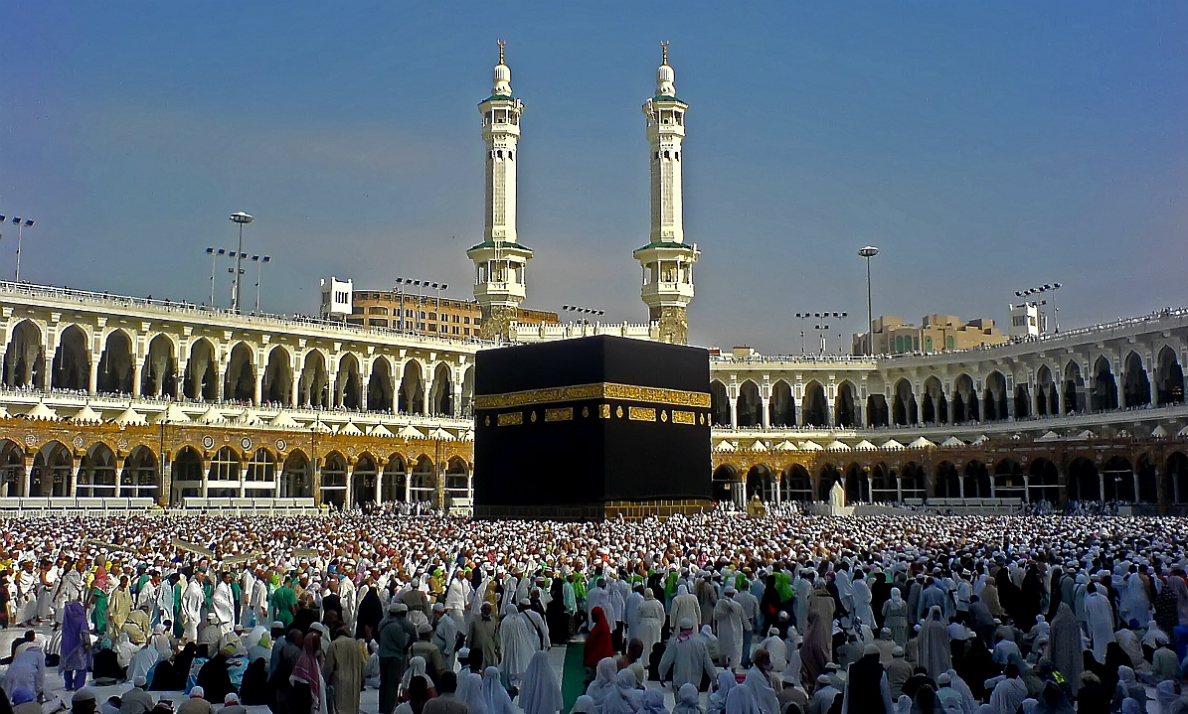

Hajj: The sacred pilgrimage to Mecca—birthplace of Prophet Muhammad—involves a series of rituals and lasts several days.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Demystifying Islamic Art

Thus far much of what you’ve seen and read directly relates to Islam. To be sure, mosques with their elegant minarets and gold-leafed Qur’ans form the spaces and objects of religious rituals. The essays below illustrate this well.

But Islamic art is far more expansive. Aesthetic traditions that fall under the category of Islamic art cover a range of buildings and objects, materials and media that have little to do with Islam as a religious practice.

Coronation Mantle, 1133/34, fabric from Byzantium or Thebes, samite, silk, gold, pearls, filigree, sapphires, garnets, glass, and cloisonné enamel, 146 x 345 cm (Schatzkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) (photo: Brad Hostetler, CC BY 2.0)

The Coronation Mantle of the 12th-century Christian ruler of Sicily, Roger II, or the 13th-century Ayyubids Canteen depicting the life cycle of Christ are great examples of this. Craftspersons of Muslim and other origins employed in Roger’s workshops created the mantle using Islamic visual references such as the palm tree in the center and Arabic writing, including the use of the Islamic (Hijri) calendar, on the hem.

Canteen, Ayyubid period, mid-13th century, Mosul School, brass, silver inlay, Syria or Northern Iraq, 45.2 x 36.7 cm (Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1941.10)

Similarly, artisans in Syria or Egypt crafted the Canteen, perhaps as a souvenir for Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land. In short, what we understand as Islamic art today was created by a spiritually and ethnically diverse group of people for Muslim and non-Muslim consumption.

But is it “Islamic”?

This is why the discipline of Islamic art often comes under scrutiny—if it encompasses artistic and architectural production unrelated to the faith, can it still be considered Islamic? For a comparable example, if we label something as Christian or Buddhist art, is it not reasonable to assume that religion inspired those creative works? Scholars of Islamic art periodically grapple with this quandary. Many engage with it vigorously, while others are more resigned to the term’s inadequacies. For the layperson, however, the phrase Islamic art immediately conjures associations with the religion and, more recently, contemporary socio-political issues covered in the news media.

Read essays that help to demystify Islamic Art

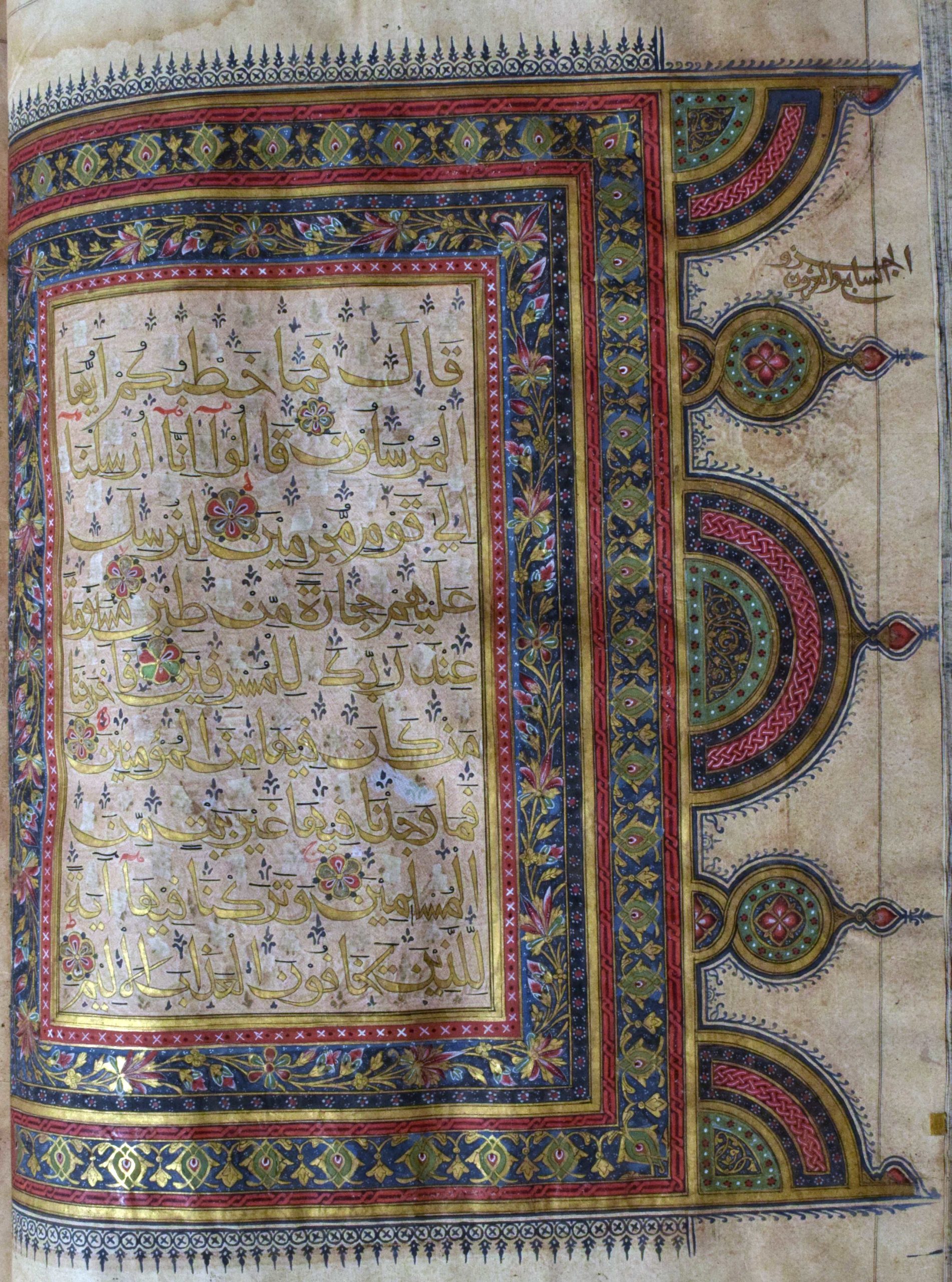

The Qur’an: The sacred text of Islam is believed to be the Word of God as revealed to the Prophet Muhammad.

Read Now >

Coronation Mantle: Made for a Christian ruler by Islamic and other artisans, this cloak is full of Islamic motifs and cosmological references.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Two Royal Figures, Iran (Saljuq period), mid-11th–mid-12th century, painted and gilded stucco (Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Figural imagery

Which leads us to another common misconception—that Islam strictly forbids the representation of figures. From a theological perspective, the only clear and consistent message from the Qur’an is against idolatry, that is, the worship of graven images. Over the centuries different Muslim communities have interpreted this injunction in relation to their own cultural and political needs and values. Some vehemently advocated against figural imagery in secular let alone religious spheres, while others enthusiastically embraced the figure in art, even when illustrating Islam’s own history. Related to this is the peculiar prevailing notion about Islamic art’s aniconic quality—the avoidance of images or icons depicting living or heavenly beings. Yet, figural imagery abounds from the earliest times of Islamic culture. Over many centuries artists have employed human and animal forms to represent a variety of subjects or as ornamentation.

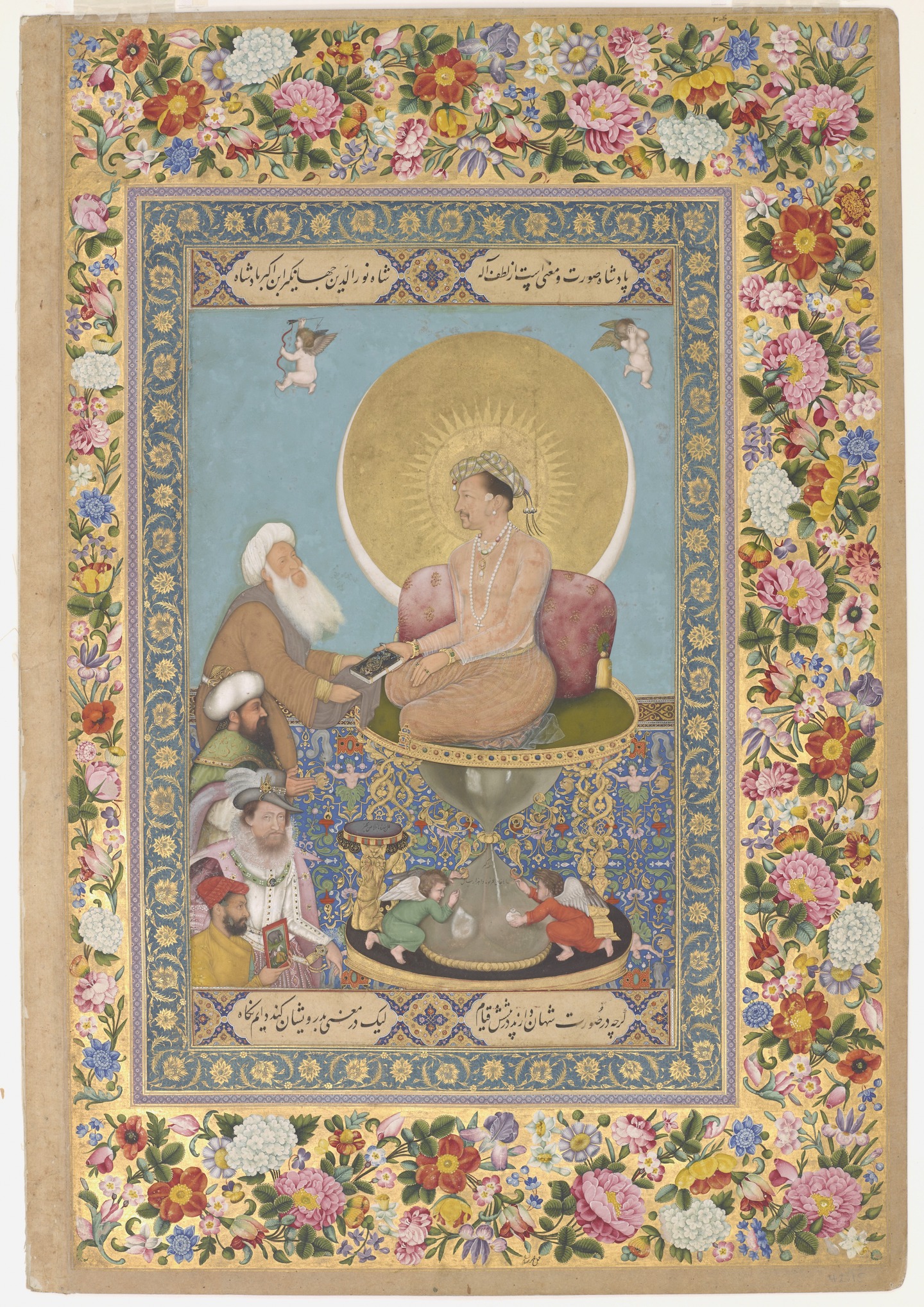

Bichitr, margins by Muhammad Sadiq, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings from the “St. Petersburg Album,” 1615–18, opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper, 46.9 × 30.7 cm (The National Museum of Asian Art)

In the following essays, you’ll take a look at Saljuq royal figures, the Persian Court of Gayumars, a pre-Islamic and mythical Iranian king, and the painting of the Mughal emperor Jahangir. In each of these instances, the representations relate to notions of kingship and political authority.

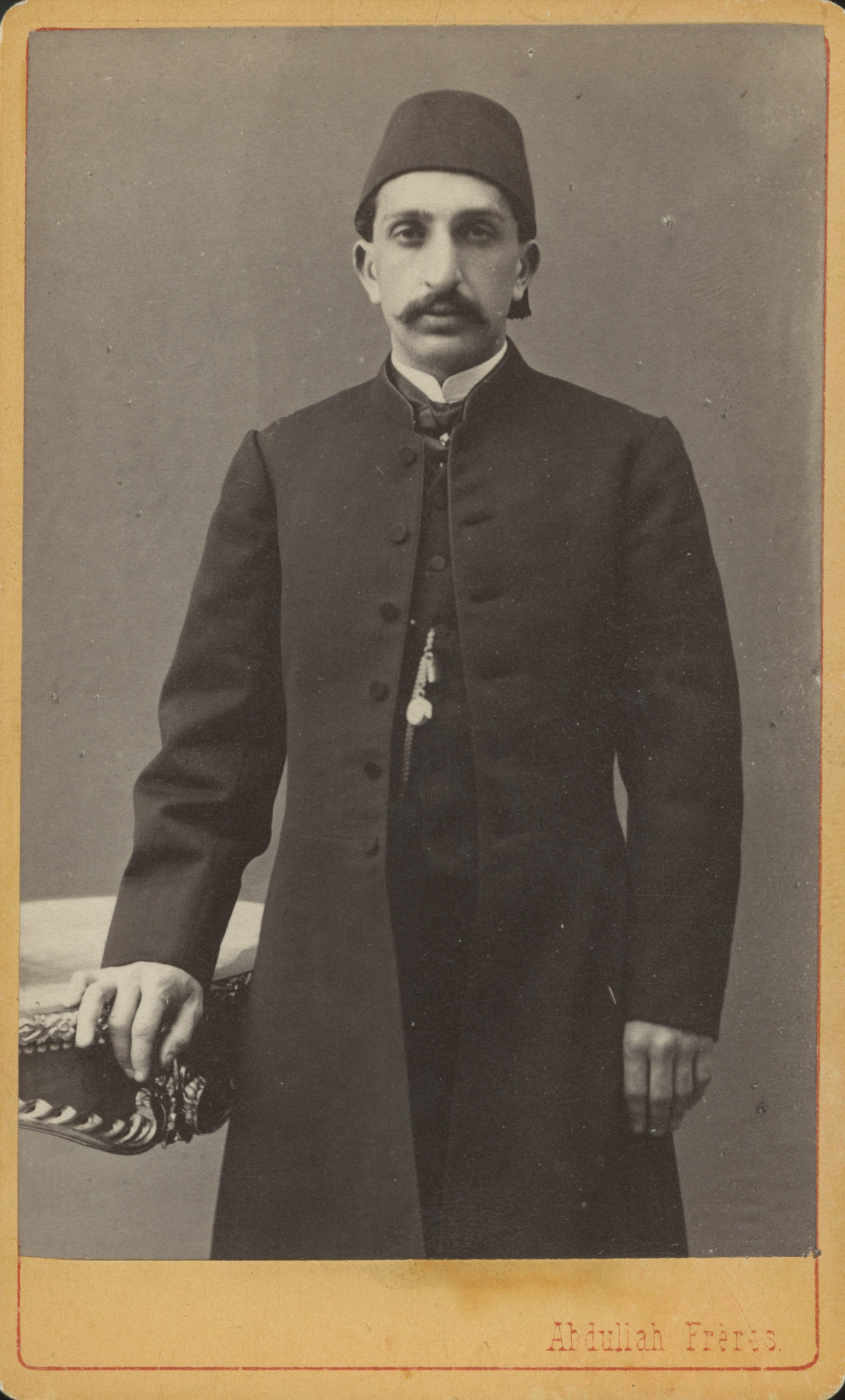

This is not too different from the use of photography in more modern times to bolster the image of a leader, such as the case with the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II. However, there are limits that are broadly observed—figural imagery is not found in the decoration of mosques or in the holy Qur’an.

Watch videos and read essays about figural imagery

Two Royal Figures: These stucco statues, with vivid costumes and distinctive round faces, may once have guarded a grand hall.

Read Now >

The Court of Gayumars: Producing this lush miniature involved many Persian artists—and likely some familiarity with Chinese sources.

Read Now >

Bichitr, Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings: From emperors to kings, the painter Bichitr mastered court portraiture.

Read Now >

Photograph of Abdülhamid II: The Ottoman Sultan understood the power of photographic representation.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Sacred or secular architecture—or both?

In a similar vein, segregating Islamic architecture into strict opposing categories of sacred or secular is too simplistic. Instead, we can look more closely at the architectures’ socio-political, theological, and legal contexts to better understand their form and function. Endowed mosque complexes, for instance, while primarily serving a religious role, were sites for social gathering, education, and charitable public services.

View of the north façade of the mosque from porticoed courtyard, Mimar Sinan, Mosque of Selim II, Edirne, Turkey, 1568–75 (photo: Casal Partiu, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Edirne’s Selim II mosque originally stood at the center of a large complex comprising libraries, hospitals, and soup kitchens among other buildings. Likewise, grand palatial structures were more than seats of political power, often embodying visual and physical attributes of just and pious rule.

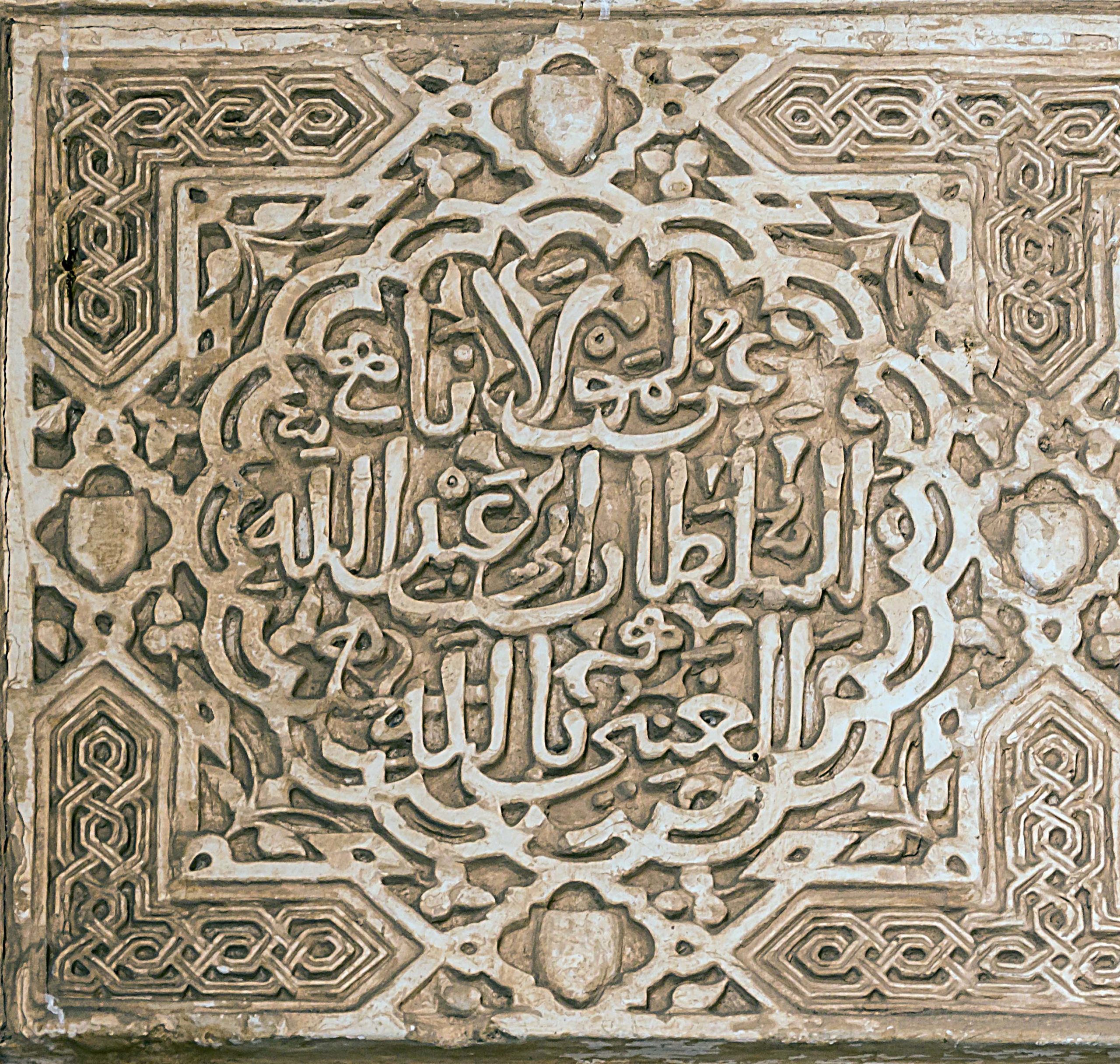

One of the many representations of the Nasrid phrase “there is no victor but Allah” in the 13th century stuccos of the Alhambra, Granada, Andalusia, Spain (photo: Jebulon, CC0 1.0)

The Alhambra’s interior stucco inscriptions exemplify the Emirate of Granada’s assertion of piety in the repeated phrase “there is no victor but Allah.” Its surrounding estates incorporated lush gardens evoking notions of Islamic paradise. All combined the vision is of an earthly realm blessed by the divine.

Read essays about Islamic architecture

Mimar Sinan, Mosque of Selim II, Edirne: A massive complex comprising of numerous buildings complicates our understanding of Islamic architecture.

Read Now >

The Alhambra: It is distinct among medieval palaces for its sophisticated planning, complex decorative programs, and its many enchanting gardens and fountains.

Read Now >/2 Completed

The “Discovery” of Islamic Art

Also propelling the discipline’s development, in the eighteenth century, British colonial enterprises in South Asia and the French invasion of Egypt in 1798 set the stage for wider exploration of Islamic cultures by British, French and, much later, German interests. British linguists and historians were particularly attentive to Arabic and Persian literary and illuminated manuscripts. In 1862, the British established the Archaeological Survey of India to locate, collect, and record information on monuments across the South Asian subcontinent.

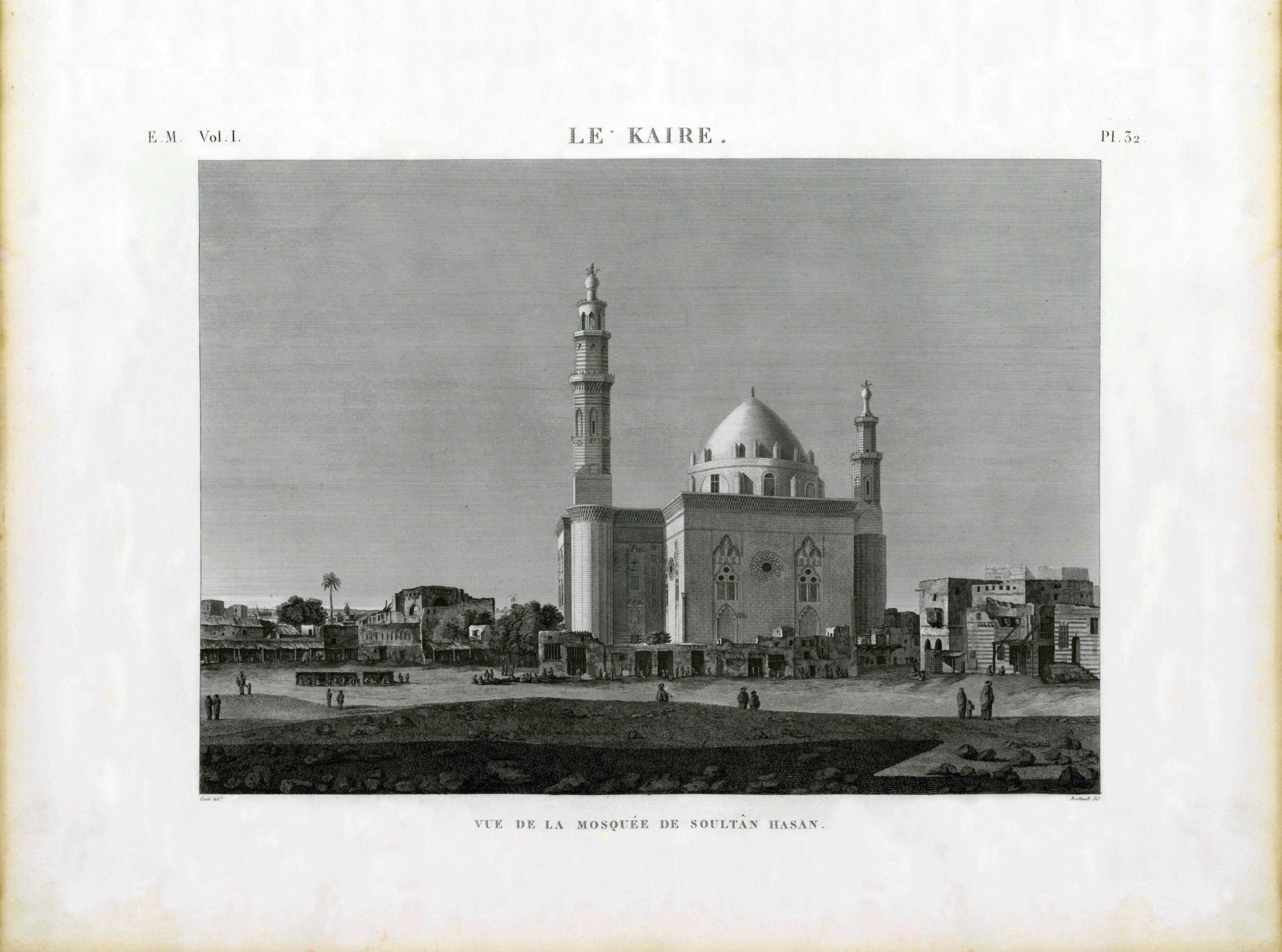

Sultan Hasan Mosque, Cairo, Egypt, 52 x 71 cm, plate in Description de l’Egypte, ou, Recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Egypte pendant l’expédition de l’armée française. État moderne, 2nd ed. (Paris: C. L. F. Panckoucke, 1822), sponsored by Napoleon I, and created by the Commission des sciences et arts d’Egypte (Library of Congress)

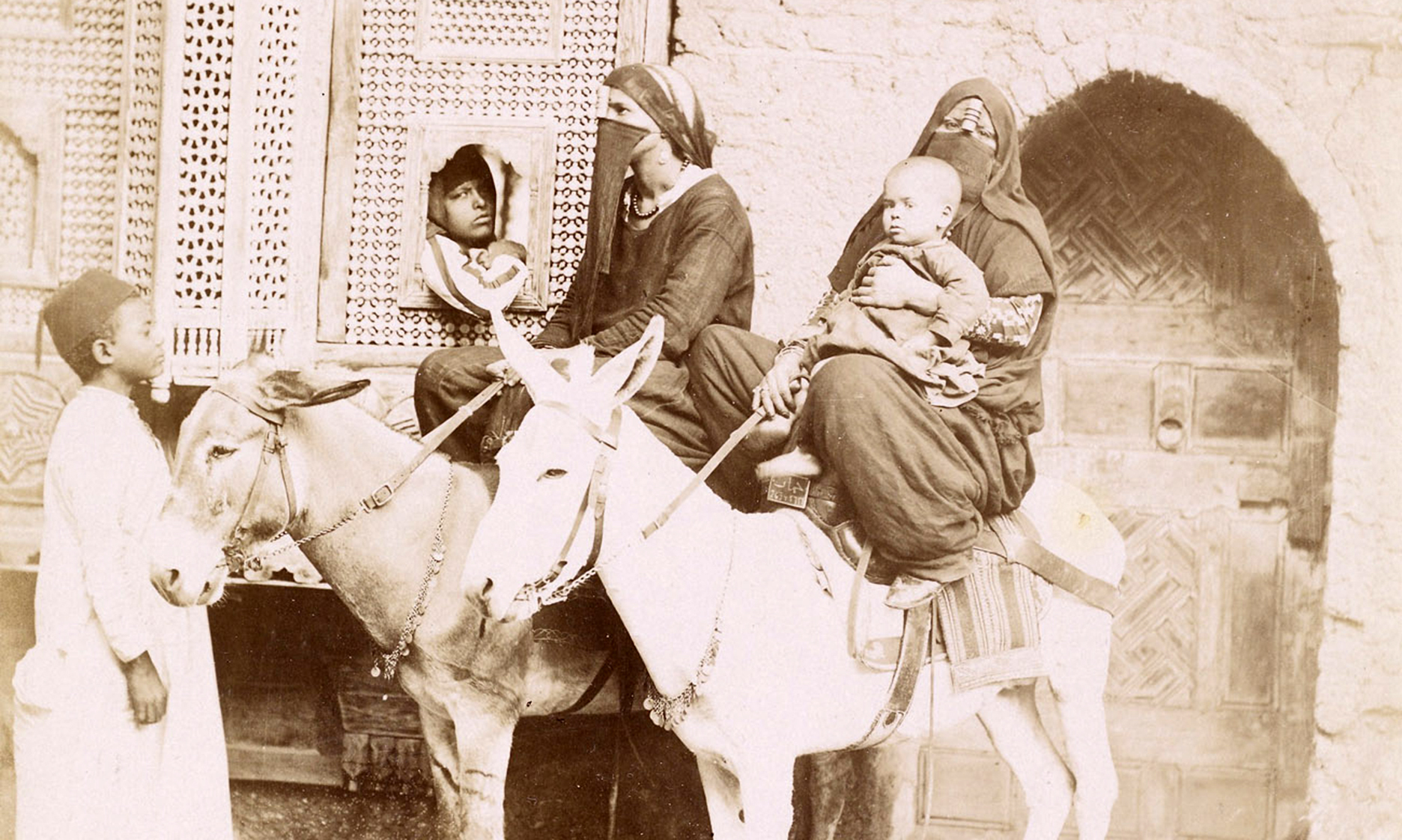

Similarly, Napoleon’s Description de l’Egypte (1809–22) provided detailed visual accounts of French “discoveries” of pharaonic as well as Islamic architecture. After its publication, European and American archaeologists, travelers, artists, photographers, and others hurriedly followed to document Biblical settings in the Holy Land, Egypt, and the greater Ottoman Empire before their rich historical patina faded in a rapidly modernizing Middle East. The vestiges of Greek, Roman, and Byzantine influences on early Islamic visual culture made such studies all the more enticing. Aided by new methods of transportation (railways), communication (telegraphs), and visual documentation (cameras), these adventurers heavily contributed to the growing appreciation of this material. Scholarly institutes sponsored missions to West Asia, North Africa, and other regions to acquire art and information.

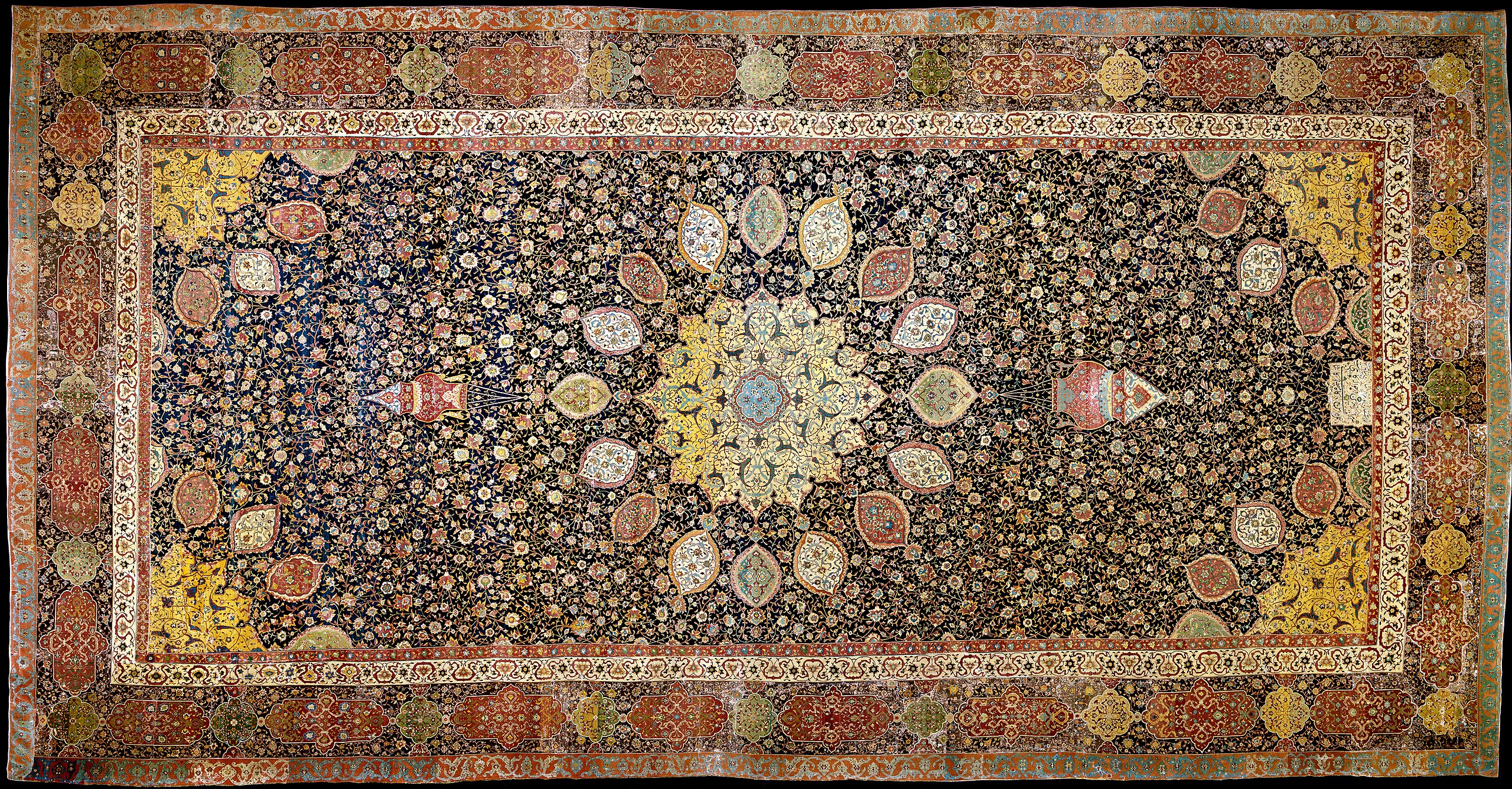

Medallion Carpet, The Ardabil Carpet, Unknown artist (Maqsud Kashani is named on the carpet’s inscription), Persian: Safavid Dynasty, silk warps and wefts with wool pile (25 million knots, 340 per sq. inch), 1539–40 C.E., Tabriz, Kashan, Isfahan or Kirman, Iran (Virginia & Albert Museum, London)

Institutional and private collectors sought a wide range of materials from coins and manuscripts to textiles, metalwork, and ceramics. In time, popular racial theories influenced Islamic art categories generating flawed hierarchies that valued Persian artistic creations above Arab or Turkish, for example. Scholars deemed the presumed “Indo-Aryan” origins of Persian art to possess stronger connections to Europe’s own genealogy. In purely visual terms, this contrived Persian superiority overrode the possibility of Arab or Turkish innovation. Therefore, the spurious notion that Persian aesthetics, especially from pre-Islamic times, undoubtedly inspired the development of Islamic art in areas as far west as Arab Spain found greater credence. This racist legacy entered texts of art and architectural history by the start of the twentieth century.

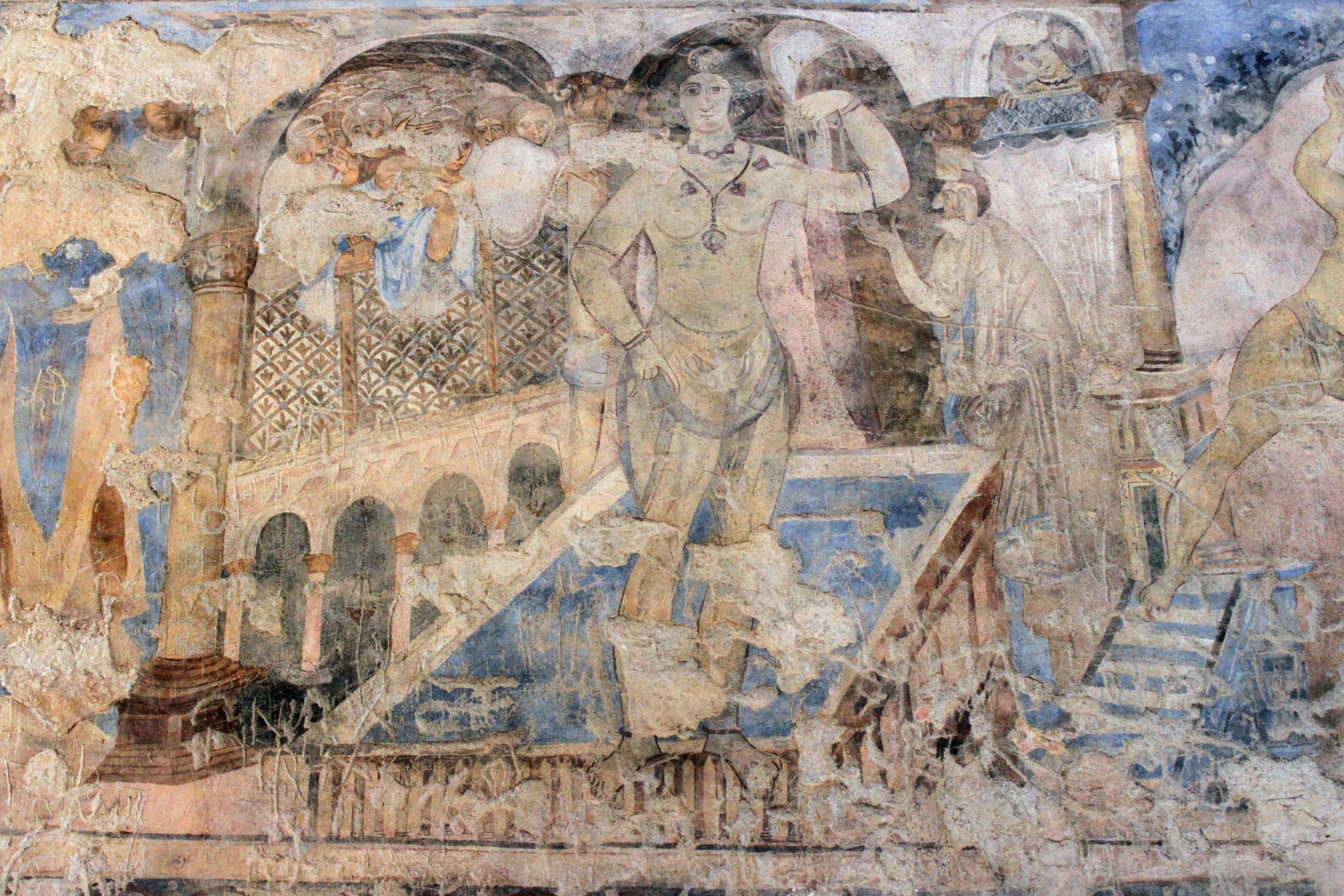

Bathing scene on west wall of west aisle of audience hall, Qasr ‘Amra, c. 730, Jordan (photo: Sean Leatherbury/Manar al-Athar)

In the following essays, you’ll find several Islamic objects and sites whose “discovery” and study emerged from other disciplinary and political interests often shaped by colonial interests.

Under the Umayyads, you’ll learn about Islamic coinage’s early reliance on Byzantine and Sasanian figural precedents before eventually settling on aniconic emblems. Mosaics and murals across Umayyad palaces, bathhouses, and hunting lodges carried on continued pre-Islamic Greco-Roman and Byzantine figural traditions, which fascinated Orientalists. For instance, Alois Musil (1868–1944)—avid traveler, scholar, and a citizen of the Habsburg Empire—found the ruined bathhouse at Qusayr ‘Amra in present-day Jordan. He caused considerable damage while attempting to illegally remove one of its frescoes. Such practices—under the pretext of scientific discovery and inquiry—deprived local communities of their cultural heritage and resulted in expansive private and public collections in Europe and the U.S. filled with architectural fragments and other artifacts.

Read essays about the "discovery" of Islamic art

Paintings in the early Islamic world: Early Islamic paintings were often vivid and imaginative; some reworked classical Greco-Roman or Sasanian motifs, and others were new.

Read Now >

Mosaics in the early Islamic world: Mosaics were highly valued throughout the first few centuries of Islam and were used alongside other precious materials as one element of elite architectural display.

Read Now >

/3 Completed

Collecting and Exhibiting Islamic Art

Medallion Carpet, “The Ardabil Carpet,” Maqsud of Kashan, Persian: Safavid Dynasty, silk warps and wefts with wool pile (25 million knots, 340 per sq. inch), 1539–40 C.E., Tabriz, Kashan, Isfahan or Kirman, Iran (now at the Victoria & Albert; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Systematic collections of Islamic art began developing in museums and libraries across Europe in the nineteenth century, often aiming to engage the greater public. Manuscripts, ceramics, wood and metalworks, glassware, and carpets moved from Islamic lands to Western collections, at times under dubious circumstances, through the hands of antiquarians, diplomats, and other enthusiasts. Even during previous centuries, Islamic art’s affinity with ornamentation was greatly valued in Europe, leading royals, nobles, and merchants to commission works from Middle Eastern craftspersons. The spoils of war and diplomatic gifts were one way that repositories in Europe acquired materials. For the most part, these items remained in private collections of royal and church treasuries. During the 19th century, international expositions, such as London’s Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851, introduced Islamic art to a much wider audience. European international exhibitions included national pavilions showcasing goods from their far flung colonies. Such exhibits reinforced colonial power dynamics, and classifications of cultures and their arts according to prevailing geopolitical and racial hierarchies. By the early twentieth century, standalone exhibitions of Islamic art in Europe, West Asia, North Africa, South Asia, and the United States had become more common. In the aftermath of World War II, even more museums around the world started collecting and displaying Islamic art.

Photographer in front of Mihrab (prayer niche), 1354–55 (A.H. 755), just after the Ilkhanid period, Madrasa Imami, Isfahan, Iran, polychrome glazed tiles, 135-1/16 x 113-11/16 inches / 343.1 x 288.7 cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

What usually remains unclear for the casual viewer, however, are the multiple lives each art object has lived before reaching the display cabinet or the afterlives of such objects at a distance from the conditions of their creation.

Mohammed ibn al-Zain, Basin (Baptistère de Saint Louis), c. 1320–40, brass inlaid with silver and gold, 22.2 x 50.2 cm, Egypt or Syria (Musée du Louvre; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The following videos focus on different kinds of objects and spaces in today’s museum collections including a Mamluk water basin in the Louvre in Paris and the Damascus Room at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. We could also return to the mantle of Roger II in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum mentioned earlier. For centuries, rulers of the Holy Roman Empire used the mantle for their coronations and, along with other coronation regalia, preserved it in the Imperial Hofburg Treasury. Today, the Treasury is associated with the Kunsthistorisches Museum and the mantle’s Islamic connections are acknowledged in its display label.

Likewise, the Louvre’s Mamluk water basin, more commonly known as Baptistère de Saint Louis, has no connection to Louis IX, the French king known as Saint Louis. Although Mamluk artisans crafted the basin, it remains unclear how it ended up in a church treasury. French monarchs later used it as a baptismal font intermittently through the 19th century before permanently placing it in the Louvre as part of the royal collection. Aside from the display of single objects like the basin, many museums are opting to recreate historical spaces in an attempt to better contextualize their function. The Metropolitan Museum’s Damascus Room offers a spatial perspective combining wood paneling, wall decor, niches with artworks, furnishings, tilework, and even a running fountain. Visitors peeking into this room can appreciate the tastes and sensibilities of the elite in late Ottoman Syria.

Newer scholarship supports interpreting the history of such objects and spaces beyond aesthetic appeal alone, increasing accessibility to and interactivity with them, especially in the context of contemporary identity negotiations, and decolonizing collections to dismantle dominant Euro-American socio-political narratives.

Watch videos that address collecting and displaying Islamic art

Qa’a (The Damascus Room) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art: The sound of the fountain led guests into this 18th-century house, where a vibrant interior stimulated ear and eye.

Read Now >

Mohammed ibn al-Zain, Basin (Baptistère de Saint Louis): Vessels like this one were typically decorated with calligraphy, but a procession of figures is featured here.

Read Now >/2 Completed

This brings us to the end of our short journey to unravel the complex historical web that is the field of Islamic art. As the discipline continues to transform, applying new theories and fresh methods to the study of Islamic visual arts will shape and sharpen our vision of its rich geographic breadth, cultural depth, and material diversity.

Notes:

[1] Until recently, Smarthistory’s collection of essays on Islamic visual culture has also demonstrated this deficit, though the editorial team has worked hard for many years to balance inclusion of different regions and periods.

Key questions to guide your reading

What are some of the challenges in defining the field of Islamic art? How did the early history of Islamic art shape the larger field?

What are some peculiarities of Islamic art that influence how people interpret it?

How do collections and exhibitions play a vital role in our understanding of the history of Islamic art?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat are some of the challenges in defining the field of Islamic art? How did the early history of Islamic art shape the larger field?

What are some peculiarities of Islamic art that influence how people interpret it?

How do collections and exhibitions play a vital role in our understanding of the history of Islamic art?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Aniconism

Archaeological Survey of India

Crystal Palace

Description de l’Egypte

Hajj

Mantle

Miniature paintings

Mosaic

Mosque

Numismatics

Orientalism

Philology

Qur’an

Learn more

Sheila S. Blair and Jonathan M. Bloom, “The Mirage of Islamic Art: Reflections on the Study of an Unwieldy Field,” The Art Bulletin 85, no. 1 (2003): pp. 152-184, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2003.10787065

Finbarr Barry Flood and Gülru Necipoğlu, “Frameworks of Islamic Art and Architectural History: Concepts, Approaches, and Historiographies,” in A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture Vol. 1, edited by Finbarr Barry Flood and Gülru Necipoğlu (John Wiley & Sons, 2017), pp. 2–56.

Christiane Gruber, ed., The Image Debate: Figural Representation in Islam and Across the World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019).

Gülru Necipoğlu, “The Concept of Islamic Art: Inherited Discourses and New Approaches,” in Islamic Art and the Museum, eds Benoit Junod, Georges Khalil, Stefan Weber, and Gerhard Wolf (London: Saqi, 2012), pp. 1–26.

Jenny Norton-Wright. ed., Curating Islamic Art Worldwide: From Malacca to Manchester (Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

Wendy M. K. Shaw, What is Islamic Art? Between Religion and Perception (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Stephen Vernoit, ed., Discovering Islamic Art: Scholars, Collectors, and Collections (London: I.B.Tauris, 2000).