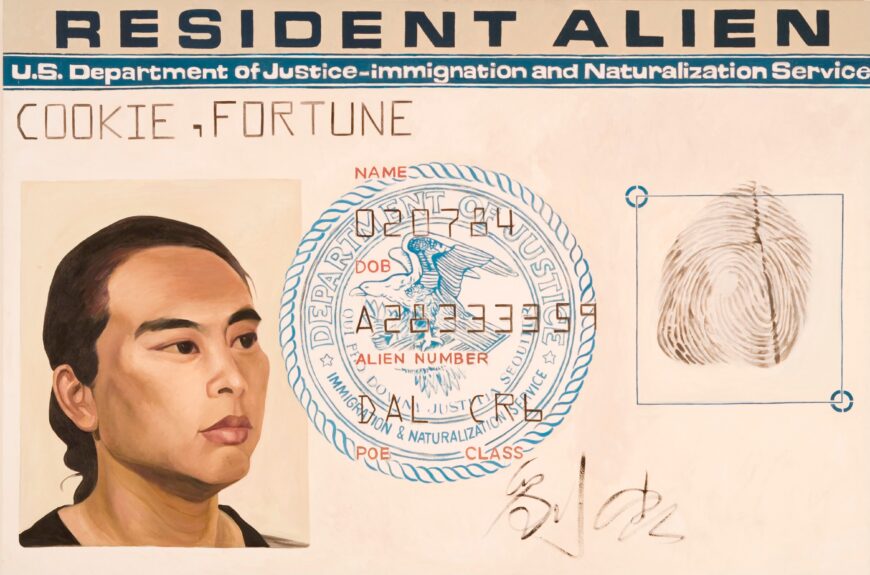

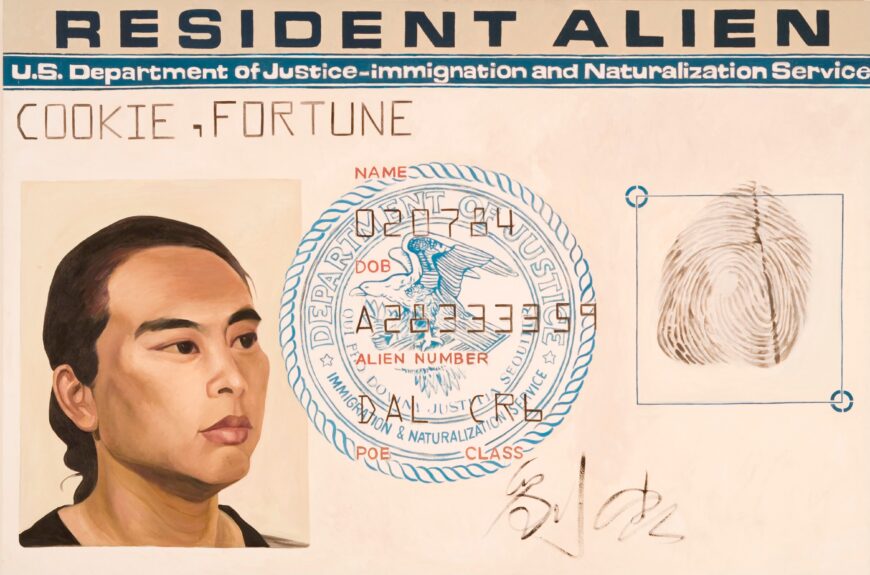

Hung Liu, Resident Alien, 1988, oil on canvas, 60 x 90 x 2 inches (San José Museum of Art) © 2025 Hung Liu Estate

Resident Alien is a painting that looks like paperwork. Though its large size and slightly uneven lettering announce the artwork’s handmade status, the official language, paperwork fields, and fingerprint register as a government document. Based on Hung Liu’s own resident alien card issued by the Immigration and Naturalization Service in 1984, the painting expresses a deeply personal experience awkwardly shaped and standardized by cookie-cutter bureaucracy that applies the same process to the varied and diverse lives of individuals.

Liu’s painting replicates the proportions of a green card. Dispassionate data fields for Name, DOB (Date of Birth), Alien Number, POE (Point of Entry), and Class in red identify, track, and label a living person as “Resident Alien.” Green card holders are typically eligible to apply for citizenship after a period of time. A three-quarter profile of Liu adheres more to Italian Renaissance portrait conventions than frontal ID photography. Reserved but noticeable brushwork creates tension between her handmade authorship and the institutional authority of a government ID card. In painting herself in a version of her own residency card, Liu wrests authorial control from INS that would identify her, number her, and track her. [1] “Resident Alien” is a self-portrait entangled in government bureaucracy.

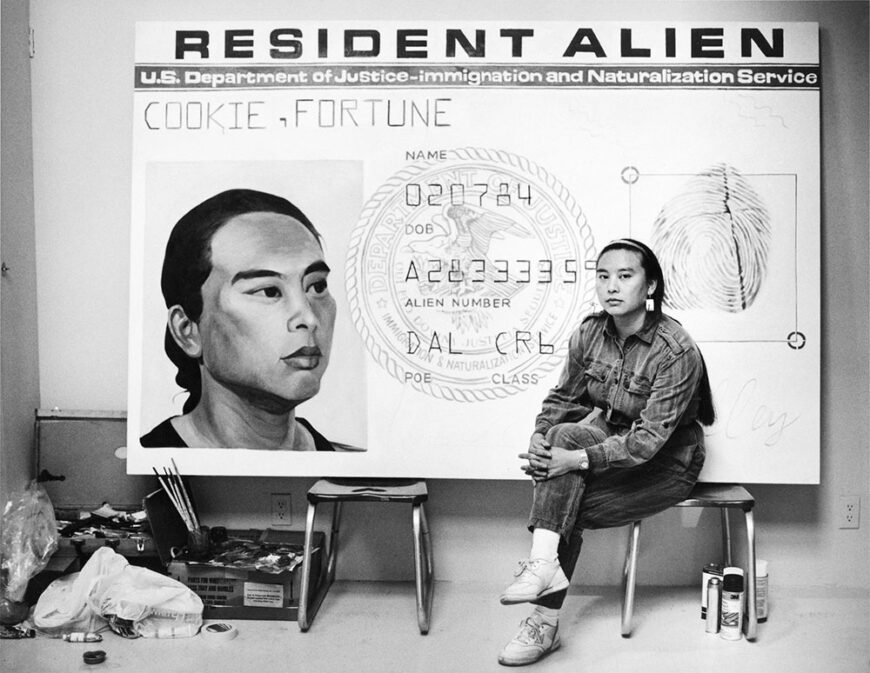

Hung Liu with Resident Alien, Capp Street Project, 1988 (photo: © Ben Blackwell)

Life and education

Liu waited four years for a visa to the United States after she received admission to the University of California, San Diego in 1980. She finally immigrated in 1984. Born in 1948 in Changchung, China, Liu directly experienced much of China’s political turmoil in the 20th century. Liu’s father, an officer in the Nationalist Army, which lost the Chinese Civil War (1927–36; 1945–49), was imprisoned in a labor camp when Liu was only six months old; Liu’s mother was forced to divorce her father. Liu would not see him again until 1994. In 1968 in her early twenties preparing for medical school, the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) sent Liu and others labelled “intellectuals” to the countryside for “reeducation” on a military farm. [2]

While threshing rice, digging ditches, caring for horses, and fertilizing fields, Liu continued to sketch in secret and take photographs of the peasants she befriended with a borrowed camera. [3] In 1972 she was able to enroll at the Beijing’s Teachers College to study art, specifically art in service of the Party. Liu said of her education, “artists were expected to be tools of propaganda.” [4] In 1981 she graduated with a degree in mural painting from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, a prestigious art school that would later graduate artists with political and critical viewpoints.

Liu wanted to further her art education. It wasn’t easy. About getting her visa, Liu said, “At every level, they tried to stop me.” [5] Nevertheless, Liu along with artists including Ai Weiwei was part of the first generation of Chinese citizens to study abroad in the United States following the normalization of relations between the United States and China in 1979. At the University of California, San Diego she studied with Allan Kaprow, the performance artist who initiated ‘Happenings,’ alongside fellow students Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson. In the United States, Liu explored the hardships of peasants and immigrants, especially women. [6] Liu eventually settled in Oakland where she taught at Mills College from 1990 until her retirement in 2014. She died in 2021 at age 73.

Self-portrait of an Asian American artist

Liu painted Resident Alien four years after she arrived in the United States. While researching historical photographs of Chinese immigrants in 1988 during a residency at the Capp Street Project in San Francisco, she decided to include her own immigration experience. The resulting exhibition was also titled “Resident Alien”—a term Liu associated with Sigourney Weaver in the movie Alien. [7]

Hung Liu, Resident Alien, 1988, oil on canvas, 60 x 90 x 2 inches (San José Museum of Art) © 2025 Hung Liu Estate

Liu plays with the naming authority of government documents in Resident Alien. Viewers scanning details will notice that Liu put her date of birth, “DOB,” as 1984, the year she arrived in the United States and began what was, in many ways, a new life. A deliberate misspelling of immigration reading “Immignation” on the top of the green card implies the United States is a country of immigrants. In a san serif font, the Resident Alien permit identifies the card holder not as Hung Liu, but as “Cookie, Fortune.” The fortune cookie, often given gratis with the check at U.S. Chinese restaurants did not originate in China, but in California, most likely in San Francisco. “Fortune cookie” is also a pejorative racist slur objectifying Chinese women Liu heard and then turned into a symbol of existing between cultures.

Though immigrating to the United States gave Liu more liberty in her artistic career, it was not without its complications. The green card itself is evidence of the required documents, bureaucratic processes, and paperwork immigrants are obliged to undergo. [8] Liu returned to the idea of living between two cultures repeatedly throughout her oeuvre; “Resident Alien” in many ways foreshadows themes in Liu’s later work focusing on the Chinese immigrants who built railroads across the United States, picture brides, the so-called “Comfort Women” abused by the occupying Imperial Japanese Armed Forces during WWII.

Liu would continue to work with photographs, complicating their documentary qualities with the expressive possibilities of paint. In a series made shortly before her death in 2021 titled “After Lange” referring to Dorothea Lange, the photographer who documented and visualized the Dust Bowl, Liu painted migrants, many of them children, and their difficult labor conditions.