To teach in a manner that respects and cares for the souls of our students is essential if we are to provide the necessary conditions where learning can most deeply and intimately begin.bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress (1994)

In Teaching to Transgress, renowned Black feminist educator bell hooks maintained that “education as the practice of freedom” was the most efficient way to a more just and truly inclusive society. I know a little something about how valuable it is to learn in an environment that is both caring and connected, because doing so at a very early age with my grandfather ultimately led to my career as an arts professional. Many nights, I waited anxiously for him to get home from work as he would often read Smithsonian magazine with me before bed. Introducing me to Sèvres porcelain, Thomas Hart Benton, and Claude Monet from a Black perspective was his way of caring for and connecting with me.

Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free, 1867, Carrara marble, 106 x 57.2 cm, 31.4 cm in diameter (Howard University Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Unfortunately, once I began to study art history, I realized the discipline itself and its traditional textbooks have never represented non-European perspectives and realities adequately or equitably. Fortunately, this makes art history ripe for new approaches to teaching that promote care and connectedness. Established during the peak of European colonization, art history as a discipline is fraught with all kinds of erasures, silences, and omissions. Thankfully, the traditional celebration of the very distorted, racist, and sexist history of Eurocentric art and art-making has finally come under scrutiny. In other words, this collection ain’t their grandfather’s art history; rather, it’s mine and yours in that it is a digital reader of essays written largely by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) scholars full of the global histories and art production of BIPOC nations and communities from the ancient world to the present.

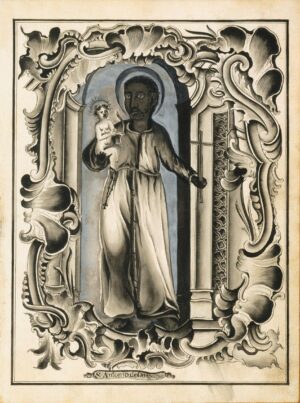

Unidentified Afro-Brazilian artists, St. Antonio de Catagerona, 18th century (Brazil), watercolor, “Compromiso da Irmandade de S. Antonio de Catagerona” (Oliveira Lima Library, Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.)

Not your grandfather’s art history: A BIPOC Reader is a free, fully digitized, openly-licensed art history resource that provides more than twenty analytical essays that seek to re-route the traditional narratives of art history with Europe and whiteness at its center. Beginning with the ancient Mediterranean and the Silk Roads, the Reader consciously challenges a narrative that centers Greece, Rome, and the Italian Renaissance to demonstrate that comprehensive understandings of art history cannot be advanced except within the broader contexts of world history. For example, essays in this collection feature the exchange and yet cultural distinctiveness between ancient Egypt and Nubia, the visual languages of power and rule in the Mongol, Persian, Timurid, and Mughal empires, and Indigenous representation of Africans in the Americas.

This collection of essays also seeks to demonstrate that the study of art objects cannot be divorced from the people and cultures who produced them. Essays on African spiritual traditions in the Atlantic world, the Afro-Spanish painter, Juan de Pareja, African American women artists like Edmonia Lewis and Sarah Mapps Douglass, and contemporary Indigenous women artists like Marie Watt highlight the makers and their stories in connection with the work they produced or continue to produce.

Drawing on recent scholarly research from BIPOC authors, the Reader’s presentation of the history of art promotes debate and robust discussion, while also providing a more expansive look at global civilization from BIPOC perspectives. Overall, Not your grandfather’s art history offers all students the chance to learn art history in much deeper and more truthful ways. It will leave readers with an appreciation of the central place of BIPOC and BIPOC cultures in world history—the same lesson my grandfather left me with.

Additional resources

Explore the essays in Not your grandfather’s art history: a BIPOC Reader