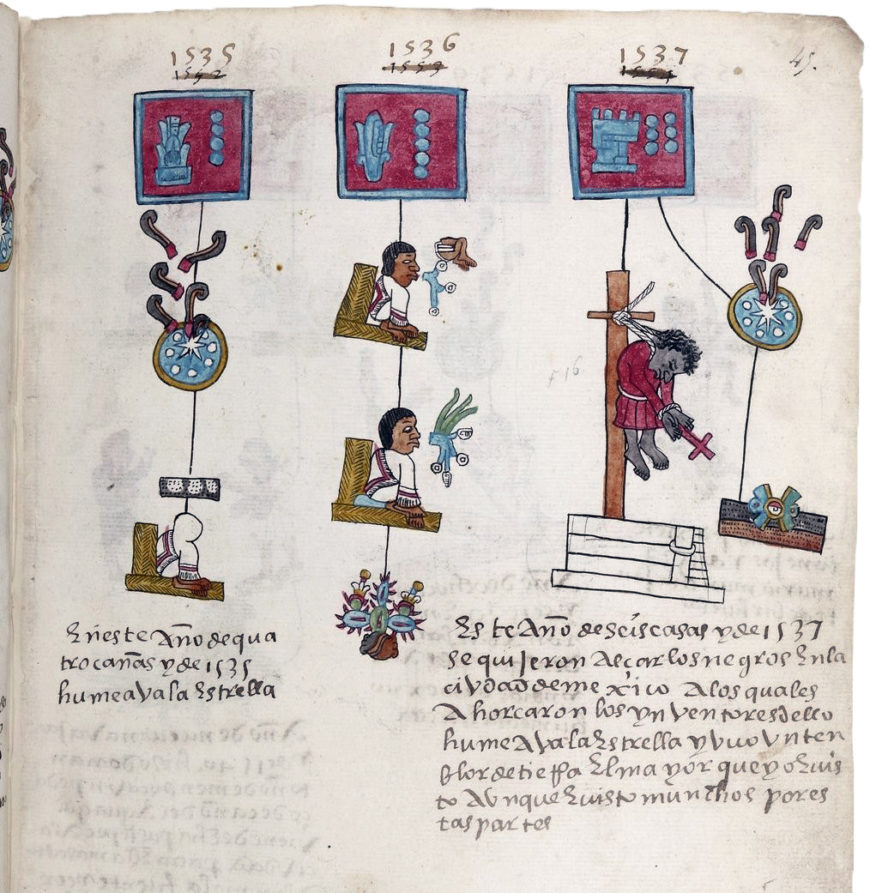

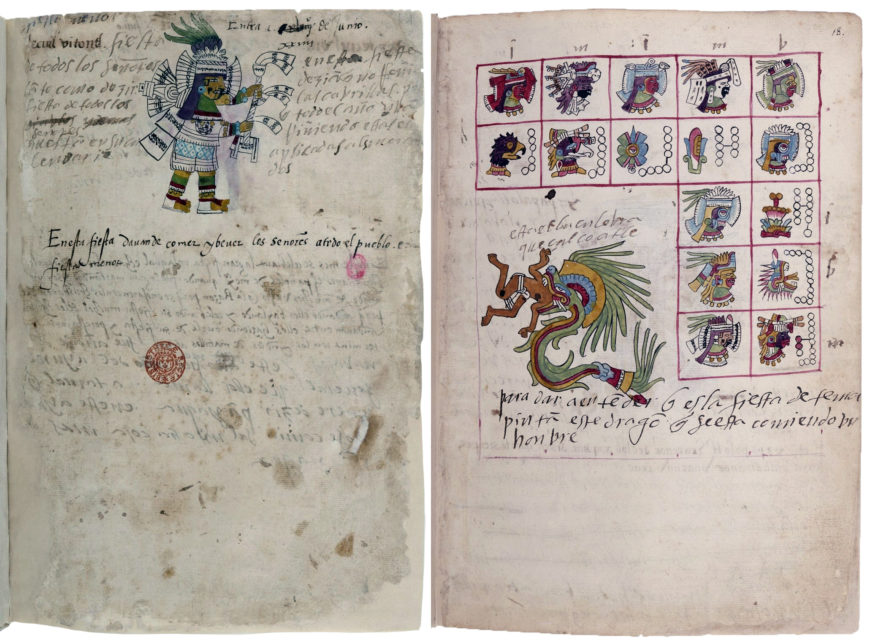

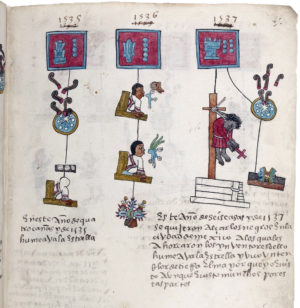

Detail from folio 45 recto, Codex Telleriano-Remensis, 16th century, 21 x 30 cm (Mexicain 385, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

A dark skinned figure holding a cross hangs by a noose from a wooden scaffold. His lifeless body slumps downward, a head of dark curls. The figure is likely the first visual rendering of an African in the Americas. It is found within the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, a manuscript created in central Mexico in the mid-sixteenth century that includes a ritual feast calendar, a divinatory almanac, and a chronicle of 350 years of Mexica history, and which was created by Indigenous artist-scribes, known in Nahuatl as tlacuiloque.

This image records the events of a slave uprising that took place in Mexico City in 1537, and along with a handful of other images, provides a view of the often violent colonial encounter between Spaniards, Africans, and Indigenous peoples, with Indigenous artists playing an important role in documenting the contact period using centuries old literary and pictorial traditions. The artists who created the Codex Telleriano-Remensis likely copied the images from several earlier Mesoamerican texts, yet the cataclysmic changes of the colonial period necessitated the introduction of new iconographies, resulting in a hybrid document that merges Indigenous and European modes of representation and record keeping.

Manuscripts through contact and conquest

In 1519 when the conquistador Hernán Cortés reached the Gulf Coast of Mexico, he was entering an empire ruled by an ethnic group called the Mexica. They ruled from their capital located in the highland basin of Mexico in a city called Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City). Some of the most revered and highly educated members of their society were the tlacuiloque (singular tlacuilo) who practiced a picture-writing tradition that combined glyphs and images for writing and record keeping, a tradition which dated back millennia in Central Mexico.

Although many Indigenous manuscripts were destroyed by Spanish colonizers after the conquest of 1521, new manuscripts were commissioned that merged Mesoamerican and European writing and artistic systems. They were created by Indigenous artists who had been trained in the tradition and who continued many Mesoamerican conventions while merging them with imported European texts and pictorial styles.

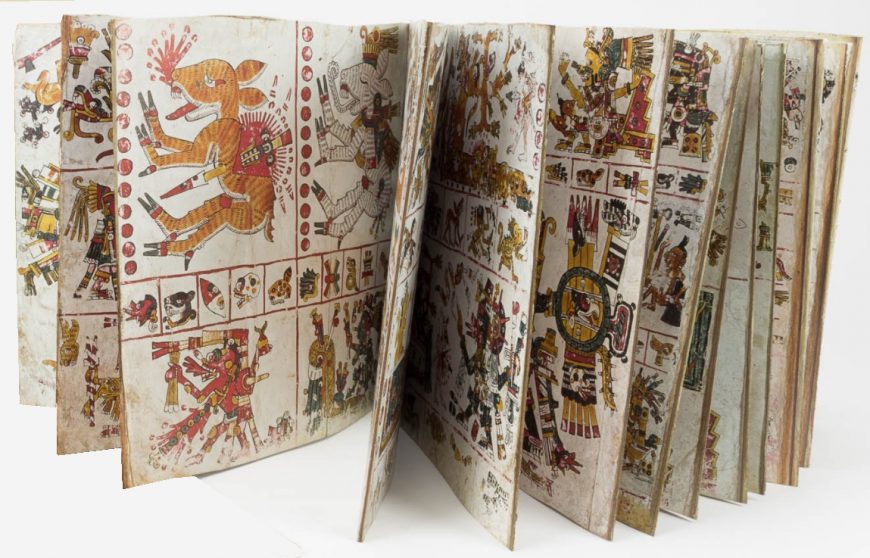

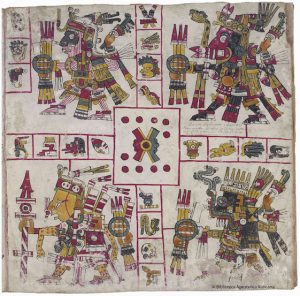

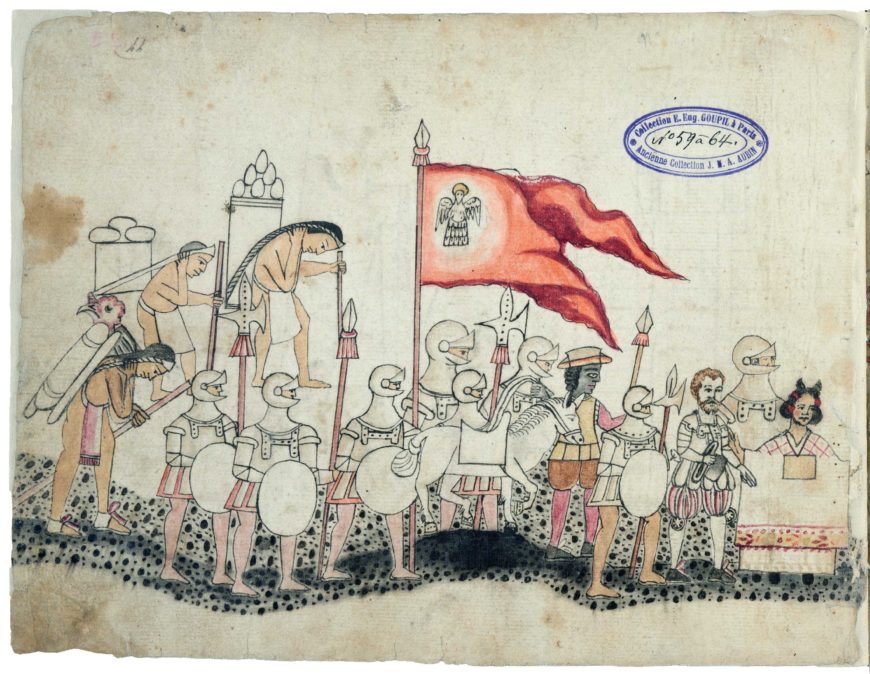

Folios 1r and Quetzalcoatl (18r), Codex Telleriano-Remensis, 16th century, 21 x 30 cm (Mexicain 385, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

One such manuscript is the Codex Telleriano-Remensis. Throughout it, the figures are rendered in profile with large heads, frontally faced eyes, and exaggerated facial features, as was typical of Mesoamerican manuscripts from Central Mexico. While the first two sections of the manuscript follow earlier Mesoamerican conventions quite closely, the chronicle (called xiuhtlapohualamoxtli) augments the traditional historical annals (recording of historic events) to include the early events of the contact and conquest period. It is within this context that a tlacuilo of the Codex Telleriano-Remensis recorded the events of the 1537 slave uprising.

Detail from folio 45 recto, Codex Telleriano-Remensis, 16th century, 21 x 30 cm (Mexicain 385, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Early colonial Indigenous manuscripts featuring images of Africans

The revolt was the result of a plot between an African “king” who along with Indigenous allies plotted to overthrow the Spaniards and take over their lands. [1] In the image that accompanies the description of the revolt, the artist incorporates a Black African phenotype into a manuscript that retains much of its Central Mexican figural style. The artists use skin color, hair style, clothing, and headgear to differentiate between the various ethnic and racial groups within the annals. The Indigenous figures on the same page, located to the left of the African figure, are shown wearing a standard male hair style with bangs. They sport tilma garments, likely fashioned from maguey fibers, identifying them as Mexica commoners.

Such observations of difference had long standing precedent in Central Mexican visual culture, which is expanded here to include newly arrived European and African groups. [2]

We see curiosity about and recording of racial difference in other written and illustrated sources from the colonial period as well. The Florentine Codex, for example, discusses Mexica Emperor Moctezuma II sending scouts to the coast to survey Cortés’s recently arrived fleet. The text, made up of ethnographic interviews of elder Nahuas, mentions in Nahuatl that some of the men had ocolochtic, or tightly curled hair. The accompanying Spanish translation, written opposite the Nahuatl, reads: “Among the Spaniards came Blacks, who had crisply curled dark hair.” Note how the Nahuatl text mentions only the hair type while the Spanish translation also makes note of their skin color. This difference is important because it reveals to us some key differences between European and Indigenous conceptions of Blackness that may explain the prominence of Africans within several early contact period Indigenous manuscripts.

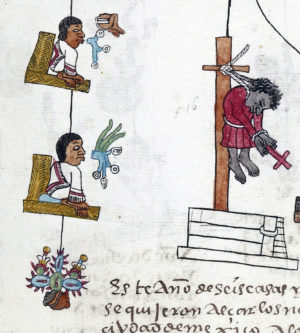

“The March of the Spaniards into Tenochtitlan,” Codex Azcatitlan, folio 23, c. 1530, 21 x 28 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

An image showing the march of Cortes into Tenochtitlan within the Codex Azcatitlan, a mid-sixteenth century manuscript created by tlacuiloque in the city of Tlatelolco, is particularly poignant for its revelation of the multi-ethnic and multi-racial reality of the colonial encounter. On this page we see two types of Indigenous people as well as two types of Spaniards (African and European).

Leading the group is Malinche, an Indigenous Nahua noblewoman from the Gulf Coast who became an interpreter for Cortés. She perhaps serves as a liminal figure between Cortés, directly behind her, and Moctezuma who was presumably on the far left hand slide of a now lost adjacent folio.

Behind Cortés and an armed henchman stands the singular African in the group holding a spear and reins belonging to the dismounted leader. This figure may reference a man named Juan Garrido, an auxiliary in Cortés’s militia who was born in Africa but lived in Seville in Spain before traveling to the Americas. Garrido famously petitioned the Spanish King Charles I for a royal pension in return for his involvement in several conquest missions between 1508 to 1519, including those of Puerto Rico, Cuba, Florida, and Mexico. [3] Garrido is pictured as part of the Spanish retinue, trailed by a grouping of armored henchmen.

Trailing Malinche, Cortés, and Garrido are three Indigenous porters, likely Tlaxcalans who had allied themselves with Cortés to defeat their enemies, the Mexica. All of the figures are differentiated via skin color, dress, hairstyle, and related objects. Malinche’s skin is painted a light brown, which contrasts with the much darker color of Garrido. She wears her hair in two horn-like braids typical of female Nahua-speakers. Again, as in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, the Black figure is rendered with cropped curly hair.

In the image, the Spanish retinue (including Malinche and Garrido) is rendered along a rolling path that serves as a horizon line. The Tlaxcalans, however, are divorced from that perspectival space and two of three seem to hover above the horizon, perhaps aligned with Indigenous modes of representation more concerned with legibility over naturalism. As some scholars have noted, European perspectival drawing was used for sections of the manuscript most relevant to Spanish interests. [4] With this subtle difference in perspective, we can imagine that the Indigenous artists and onlookers pictured both Garrido and Malinche as Spanish while the Tlaxcalans retain their Indigenous identity.

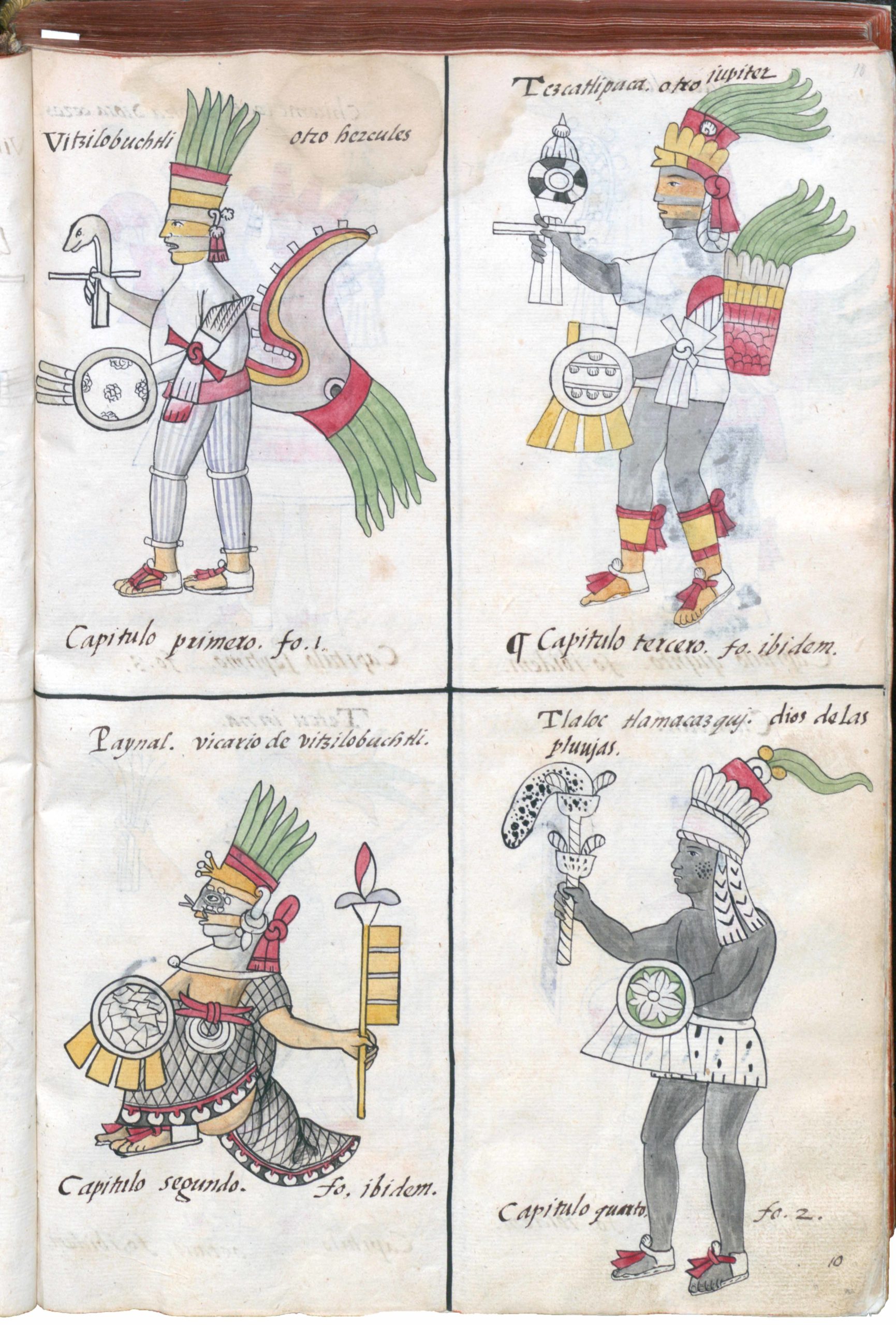

Four deities, two of whom are shown with black skin, on folio 10r of Bernardino de Sahagún and collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain, also called the Florentine Codex, vol. 1, book 1, 1575–77, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open (approx.): 32 x 43 cm, closed (approx.): 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

Blackness through Indigenous eyes

The earlier interest by Indigenous artists of the Codex Telleriano-Remensis and Codex Azcatitlan likely displays a view of Blackness that was still unentangled with Spanish notions of white supremacy and anti-Blackness. Indeed the color Black and even Black or Blackened skin held positive connotations in Mesoamerican worldview. In the Florentine Codex the Black conquistadors are referred to as “soiled gods,” connecting them with sacred power associated with darkness. Mexica priests and political leaders at times would paint their bodies Black using salves derived from potent hallucinogenic or poisonous plants. The Black paint associated the body with the power of male deities and provided bodily protection during rituals, especially those involving caves—dark spaces that were seen as transitional portals of emergence and descent into the underworld. Given that Black skin held such prestige, it follows that Indigenous artists and informants took special note of the dark skin of certain members of the Spanish retinue.

Battle scene (detail), Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City)

These manuscripts are our earliest visual records of the encounter, and feature an Indigenous viewpoint. Later visual culture, dominated by Hispanized artists, tend to leave out the African presence in images that showed the conquest. By the seventeenth century, for example, the conquest scene pictured on a folding screen or biombo displays the homogenous binary of white European Spaniards versus brown Indigenous Mexica. Multiethnic categories are largely ignored and the Africans amongst the Spanish retinue are completely absent.

Juan Correa, Biombo, allegory of Africa (detail), side showing an allegory of the Four Continents, c. 1675, oil and gilding, 199 x 556 cm (Museo Soumaya, Mexico City)

By the seventeenth century, Black Africans instead came to be seen largely in mythologized or stereotyped imagery. This could take the form of positive images of Blackness, such as in images of Black saints or the Black magus. Black figures were also pictured as personifications of Africa within a grouping of four, each figure serving as an allegory for one of the four known continents. Afro descendants were also pictured within casta paintings of the eighteenth century, oftentimes embodying negative stereotypes associated with Blackness in a white supremacist society.

Detail from folio 45 recto, Codex Telleriano-Remensis, 16th century, 21 x 30 cm (Mexicain 385, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The image of the March into Tenochtitlan in the Codex Azcatitlan is notable for its articulation of the multi-racial and multi-ethnic realities of the Spanish conquest. The Indigenous authors pay particular attention to the Black member of the Spanish retinue, giving him pride of place within the composition. Similarly, the image from the Codex Telleriano-Remens is notable for its recoding of an African figure. Combined with Mesoamerican glyphs, the tlacuilo illustrates the discord of the colonial period, possibly alluding to alliances between Black and Indigenous rebels during the 1537 uprising in Mexico City. Taken together, the images provide us with a new precedent for the recording of Africans and their descendants in the Americas, recorded by Indigenous artists rather than the assumption that European artists were the first to document and record the various peoples who formed the fabric of a burgeoning society. The images of Africans recorded by the Indigenous tlacuiloque stand out in the visual record for their early date and the ways that they add nuance to our understanding of the cross-cultural encounters of the early colonial period.

Notes:

[1] This uprising is also discussed in a letter from Viceroy Mendoza to Charles I of Spain.

[2] This essay is adapted from Elena FitzParick Sifford, “Mexican Manuscripts and the First Images of Africans in the Americas,”Ethnohistory 66, no. 2 (April 2019): pp. 223–248.

[3] For more on Garrido see Ricardo Alegría, Juan Garrido, el Conquistador Negro en las Antillas, Florida, México y California (San Juan: Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y el Caribe, 1990).

[4] Federico Navarrete, “The Hidden Codes of the Codex Azcatitlan,” Res 45 (Spring 2004): pp. 144–60.

Additional resources

Eloise Quiñones Keber, Codex Telleriano-Remensis: Ritual, Divination, and History in a Pictorial Aztec Manuscript (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995).