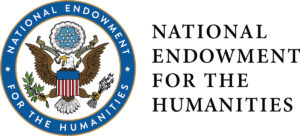

Sarah Mapps Douglass, Lady while you are young, and beautiful…, c.1836–37, in the Elizabeth Smith Friendship Album (Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University)

Sometime in 1836 or 1837, Philadelphia school teacher Sarah Mapps Douglass painted a watercolor of a floral bouquet in the friendship album of Elizabeth Smith. A large pink rose blossom and diminutive rosebud dominate the composition, while more humble flowers—a dainty sprig of blue forget-me-nots and two specimens of the purple, yellow, and white pansy known as heart’s ease—accent the larger stem. The seemingly innocuous painting might initially strike viewers as little more than a conventional display of feminine accomplishment typical of the period, just the sort of trifle that one refined lady might offer another as a token of friendship.

However, the different racial identities of the women involved marks the exchange as especially unusual: the painter, Sarah Mapps Douglass, was a free Black woman, while the teenaged Elizabeth Smith, daughter of committed abolitionists and owner of the album, was white. Moreover, beneath the image Douglass penned a powerful inscription whose sharp puns dramatically transformed the significance of her flower picture:

Lady, while you are young and beautiful ‘Forget Not’ the slave, so shall ‘Heart’s Ease’ ever attend you. (emphasis added)

Race, gender, and friendship albums

Friendship albums were something of a fad among fashionable young women of the period. They were bound volumes that contained blank leaves upon which the owner’s invited friends would offer gifts of writing or sometimes drawings or small paintings. [1] Existing at a unique nexus of the public and the private, the albums were often displayed in a parlor for the admiration of visitors who might also be invited to make an entry and might even be taken home for a few days by a friend who would make an inscription in the book and inevitably also read it. Therefore, although the offerings made therein might be personally addressed to the book’s owner, friendship albums—unlike a private diary entry or personal letter and more akin to a today’s social media posts—were also very much intended to be seen by others. Moreover, not limited to the owner’s close circle of friends, as much as the albums might represent bonds of affection between their owners and inscribers, they also traced networks of association among their contributors and put on display the social status, education, personality, and occasionally the politics of those who recorded entries between their covers.

Title Page, Elizabeth Smith Friendship Album, c. 1836–37 (Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University)

Although most friendship books were maintained by and circulated among white women, scholars (like Jasmine Nicole Cobb, Erica Armstrong Dunbar, and Elise Kammerer) have recently brought attention to four extant albums belonging to free Black women. [2] However, Smith’s album is something of an anomaly in that it was owned by a white woman, but includes many of the same signatories as these four and offers a unique opportunity to consider how elite free Black women involved in the interracial anti-slavery circles constructed and communicated their raced, gendered, and classed identities when directly addressing their white associates rather each other.

In the decades before the U.S. Civil War, support for the abolition of slavery did not necessarily correspond to a belief in Black social equality, and some women’s antislavery organizations explicitly excluded African American women from membership. Challenging the popular ideals of proper “ladyhood” that inherently excluded Black women, the entries that Sarah Mapps Douglass and other free African American women recorded in Smith’s friendship album explicitly demonstrated and insistently asserted their equal standing with the white ladies with whom they associated. Moreover, although almost entirely unknown to scholars of American art, the images that Douglass and peers made in friendship albums may be the earliest documented signed art works by African American women.

Sarah Mapps Douglass

Born in 1806 to a prominent, relatively well-to-do, and politically engaged family, Sarah Mapps Douglass features prominently in the history of Philadelphia’s nineteenth-century free Black elite. She was a tireless anti-slavery activist, a committed teacher of young Black women for over fifty years, a devoted Quaker who challenged their segregated seating at meetings, and the first African American woman to attend the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania! She is, however, almost never mentioned as an artist. [3] That title went to her brother Robert Douglass, Jr., a painter who reputedly studied with Thomas Sully of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts before opening his own portrait and daguerreotype studio in Philadelphia. Gender, as much if not more than skill, undoubtedly informed the siblings’ divergent artistic trajectories. While Robert enjoyed opportunities for advanced artistic study in Europe and support in pursuing a professional career as an artist, gendered mid-nineteenth-century standards of respectability, which the free middle-class African Americans very strictly observed, limited Sarah’s artist expression to subjects and venues deemed appropriate for her sex. Sarah Douglass’s work, hidden between the covers of dusty albums or sealed inside the envelopes of private letters in attics and archives, has only very recently come to light. Her example encourages scholars to broaden both our understanding of what constitutes art worthy of critical study and our investigation of where we might find it.

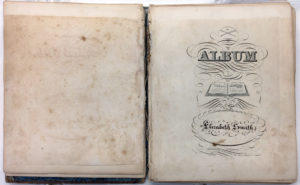

Sarah Mapps Douglass, “Fuchsia,” in Friendship Album of Mary Anne Dickerson, mid-19th century, watercolor (Library Company of Philadelphia)

Say it with flowers: Visual-verbal floriography

Although a number of Black women contributed pictorial offerings to the albums of their friends, Sarah Douglass was exceptional both for the number of paintings she made (more than half of the graphic entries by women in the four extant African American friendship albums are hers) and for the considerable skill her works demonstrate. At least eight Douglass paintings survive, most of them preserved in friendship albums. However, two other works, not recorded in albums, although no longer extant have been specifically documented, and period sources like newspaper advertisements and journal entries indicate a lifelong and varied art practice. Douglass’s skill likely derived from a combination of natural ability, training, and personal interest. Through Quaker-run institutions, under the tutelage of private instructors, and in special schools organized by free African American families, her parents ensured that the Douglass siblings received superior educations (including, for example, lessons in literature and French and, especially considering her brother Robert’s profession, perhaps some artistic instruction).

James Andrews, botanical illustration from Lessons in Flower Painting, Plate 12 (London: Charles Tilt, 1836) (Getty Research Institute)

Douglass augmented whatever training she might have enjoyed in her youth with self-study from books. As Jasmine Nichole Cobb has traced, for her contribution to Mary Anne Dickerson’s friendship album, Douglass meticulously copied a branch with four hanging bells of fuchsia from James Andrews’s 1836 manual Lessons in Flower Painting: A Series of Easy and Progressive Studies. Moreover, to the extent that gender norms in her community allowed it, Douglass’s artistic ambitions seem to have surpassed that of an amateur. An 1844 notice for Robert Douglass’s artistic services in the Pennsylvania Freeman also advertised “Marking on linen, silk, &c” by “S.M.D.”, indicating that the artist successfully parlayed her skills into a modest business selling painted textiles or templates for embroidery out of her brother’s studio. [4] This enterprise suggests both a desire for recognition beyond her circle of friends and a necessity to augment her income that would have been more common than not among African American women, even those of the respectable middle class. [5]

Sarah Mapps Douglass, “Forget-me-not,” in Friendship Album of Martina Dickerson, mid-19th century, watercolor (Library Company of Philadelphia)

Like her peers, Douglass painted flowers almost exclusively. The rise of the “language of flowers,” through which floral specimens—actual, lyric, or graphic—functioned metaphorically, coincided with the popularity of friendship albums in the United States and was part of the culture of sentiment that informed women’s expressive practices in the mid-nineteenth century. [6] Flower references—visual and verbal—dominated Black women’s contributions to their friends’ album books. Some offered generic bouquets whose primary significance was in their beauty while others drew and painted roses, lilies, and especially forget-me-nots to express more specific sentiments. Likewise, Douglass also communicated primarily through pictorial and poetic floral metaphors.

Some of her entries offer fairly mundane expressions of period sentimentality similar to her peers’. For example, inside an ornate embossed frame in Martina Dickerson’s album, the artist painted a simple, delicately rendered sprig of forget-me-nots. Douglass beautifully accents the Y-shaped stalk of blue flowers by interlacing it with gracefully curving, leafy green stems that end in small clusters of red petals. Inscribed with the words “Forget me not” and signed “S.M.D.”, the straightforward work exemplifies a conventional token of friendship.

Some of Douglass’s entries, however, convey greater depth, offering profound insights about the experience of Black womanhood and representing what Cobb identifies as an “optics of respectability.” For example, on the page directly following Douglass’s Fuchsia, the artist illuminated her work with verses whose metaphors transform it into a floriographic treatise of nineteenth-century Black feminism:

All the spears of fuchsia droop their heads toward the

grounds in such a manner that their inner beauties can

only be discerned when they are somewhat above the eye

of the spectator . . . / . . . this modest bending of the head . . ./

Beautifully and significantly typifying modesty.

Although more subtle than her entry in Smith’s album, here Douglass similarly transforms the genteel language of flowers into a political statement as she simultaneously extolls bodily modesty—a sartorial and behavioral strategy adopted by free Black women to combat racist perceptions of women of African descent as inordinately sexual—while emphasizing the physical beauty of women of African descent at a time when it was popularly derided.

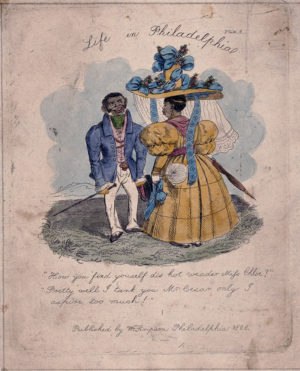

E. W. Clay, etching of an African American woman talking with a man in the street, from Life in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: W. Simpson, 1828), Plate 4 (Library of Congress)

The politics of respectability that informed the lives of all free Black Philadelphians particularly dictated the lives of the community’s women. Held to rigorous standards of dress, comportment, and gender appropriate accomplishment, their public performance of “ladyhood” aimed to demonstrate Black potential and African-American fitness for full inclusion in American society. This amounted to nothing short of a political act because, as E. W. Clay’s popular series of cartoons Life in Philadelphia cartoons confirm, for most white Philadelphians, “Black lady” constituted an oxymoron. Produced around the same time that Douglass and her peers showcased their ladyhood in friendship albums, Clay’s series lampooned the pretensions of the free Black community, often using buffoonish caricatures of Black women who dared aspire to the title of lady to do so.

Yet, it is precisely to a “lady” that Douglass addresses the pointed puns of verse she inscribes in Smith’s friendship album and that transform her painted floral bouquet into a radical political statement. The artist’s opening words directed toward Smith, “Lady, while you are young and beautiful…,” might be considered simply appropriate for (or even meant to convey deference to) her young friend whose whiteness meant that her status as a lady would not have been in question. However, in addressing young Elizabeth Smith as “Lady,” Douglass’s work also boldly claims the title for herself—as Smith’s good friend, granted the privileged place of first entry in her album, and as one whose pictorial and poetic floriography demonstrates her mastery of the parlance of genteel femininity. Moreover, Douglass’s use of the second person imperative, with its implied and flexible “you,” also claims ladyhood for the other Black women with whom Smith shared her album and who would have read these words as though also addressed to them. The imperative construction of Douglass’s verse—commanding its audience to “‘Forget Not’ the slave, so shall ‘Heart’s Ease’ ever attend you”—also amplifies the bold political gesture of Douglass’s offering. Despite the prettiness of the presentation and the deference to its addressee that “Lady” might suggest, Douglass nonetheless constructs the work in the form of a command issued from a Black woman to a white one.

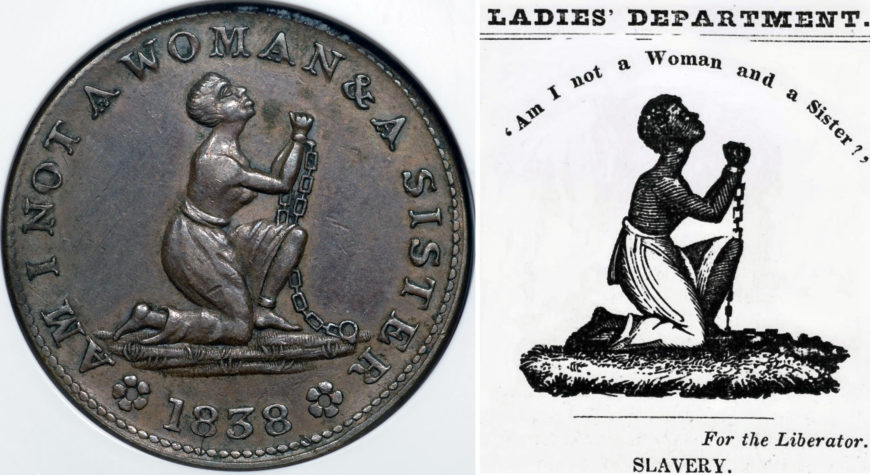

Left: Am I Not A Woman & A Sister Anti-Slavery Hard Times Token, 1838, Copper, Gibbs, Gardner, and Company; American Anti-Slavery Society (publisher), 2.7 cm diameter (Mount Holyoke College Art Museum); Heading for the “Ladies Department,” from William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper ‘The Liberator,’ 1832

Finally, Douglass’s offering to Elizabeth Smith’s friendship album critically redefines the acceptable vocations of ladyhood. With her strategic pairing of pretty picture and punning poetry, the artist proclaims abolitionism as an unequivocally appropriate vocation for ladies, using the coded language of feminine refinement to call her audience’s attention to a struggle that convention insisted was outside the realm of a proper lady’s concern. In appropriating and redeploying the markers of white, middle-class respectability for women, Douglass’s offering insists that ladies—both Black and white—are called to the abolitionist cause. Challenging the popular abolitionist slogan “Am I Not a Woman and a Sister?,” which circulated widely through visual and material culture and featured a disempowered kneeling enslaved woman pleading for confirmation of her humanity and equality, Douglass refuses to deal in interrogatives that question her status as an equal. Instead, she issues a mandate to her white friend, thereby asserting her own unequivocal equality as woman and sister, and in so doing, creating a space for the other free Black women who engaged with Smith’s album to do the same.

Notes:

An earlier version of this essay was published in the Fall 2020 issue Tulane University’s School of Liberal Arts Magazine.

[1] For more general information on friendship albums, their circulation, and their use as an index of education, refinement, and social class, see Laura Zebuhr, “The Work of Friendship in Nineteenth-Century American Friendship Album Verses,” American Literature 87, no. 3 (September 2015).

[2] The albums of Amy Matilda Cassey and the sisters Martina and Mary Anne Dickerson are at the Library Company of Philadelphia while Mary Wood Forten’s album is at the Moorland-Springarn Research Center at Howard University, also home to Elizabeth Smith’s album.

[3] A notable exception is Steven Loring Jones, “A Keen Sense of the Artistic: African American Material Culture in 19th-Century Philadelphia,” The International Review of African American Art 12 (January 1995), pp. 4–29, where the author first encountered discussion of the albums. Particularly exceptional is Jones’s use of the title “artist” to describe Sarah Mapps Douglass. More recently, Lisa Farrington included Douglass in her important survey text, African American Art: A Visual and Cultural History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 73–75, briefly discussing the artist and her work within an art historical context.

[4] According to Marie J. Lindhorst, whose meticulously researched dissertation offers the most comprehensive historical account of Sarah Mapps Douglass’s life, the advertisement ran repeatedly over several months. See Marie J. Lindhorst, “Sarah Mapps Douglass: The Emergence of an African American educator/activist in Nineteenth Century Philadelphia,” Doctoral Dissertation (The Pennsylvania State University, 1995), p. 142, note 25.

[5] Erica Armstrong Dunbar, A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), p. 121.

[6] For more information, see Shirley Samuels, ed. The Culture of Sentiment : Race, Gender, and Sentimentality in 19th-Century America (New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).

Additional resources

Jasmine Nichole Cobb, “Optics of Respectability: Women, Vision, and the Black Private Sphere,” in Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2015), pp. 66–110.

Erica Armstrong Dunbar, “A Mental and Moral Feast: Reading, Writing, and Sentimentality in Black Philadelphia,” in A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), pp. 120–147.

Aston Gonzalez, “The Art of Racial Politics: The Work of Robert Douglass Jr., 1833–46.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 138, no. 1 (2014): pp. 5–37.

Elise Kammerer, “Activism behind the Veil of Sentimentality: The Amy Matilda Cassey Friendship Album,” Critical Studies 2 (September 2016): pp. 112–121.

Britt Russert, “Sarah’s Cabinet: Fugitive Science in and beyond the Parlor,” in Fugitive Science: Empiricism and Freedom in Early African American Culture (New York: New York University Press, 2017), pp. 181–218.