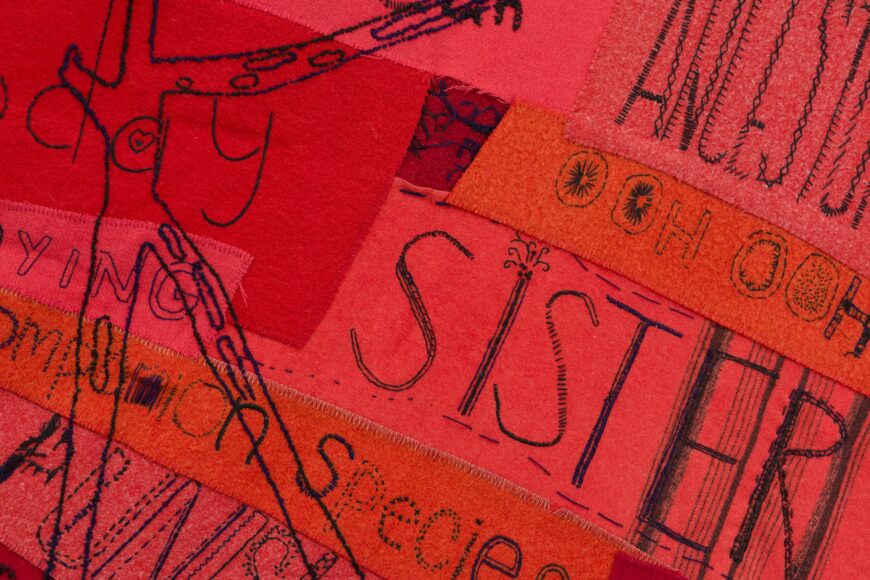

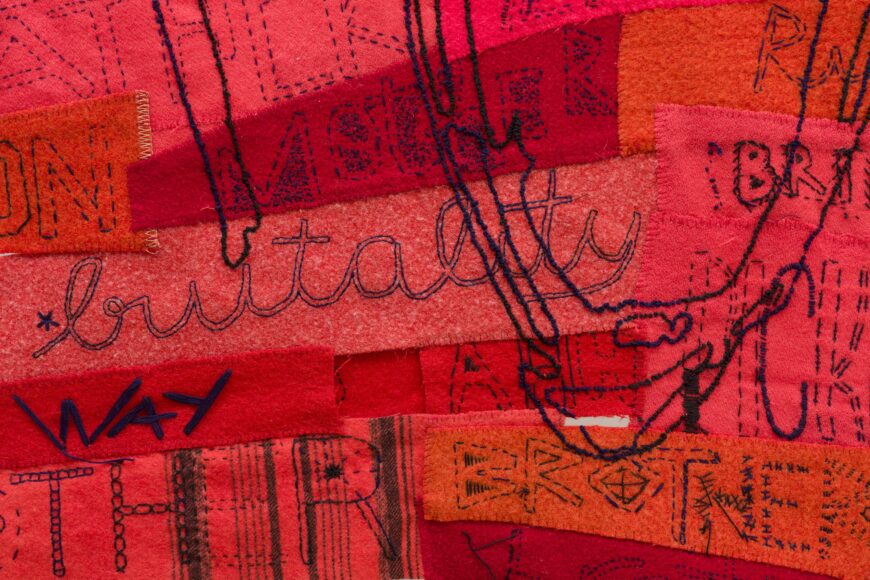

Marie Watt, Companion Species (Speech Bubble), 2019, reclaimed wool blankets, embroidery floss, and thread, 136 5/8 x 198 1/2 inches (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville; photo: Edward C. Robison III) © Marie Watt

Mother, mother

There’s too many of you crying…

Picket lines and picket signs

Don’t punish me with brutality

Talk to me

So you can see

Oh, what’s going on (What’s going on)Marvin Gaye, “What’s Going On” (1969)

As a kid who grew up in the 1970s, Marie Watt heard Marvin Gaye’s song “What’s Going On” (written in 1969, released in 1971) on the radio in the backseat of a breezy, uninsulated station wagon. It wasn’t until years later though, when she began to consider the connectedness of all people and things, that she integrated the song and its message into her artistic practice. Hearing “What’s Going On” recently, Watt realized that Marvin Gaye was not just talking about biological relationships, but about all relationships that connect us as species. In Indigenous relations, the call to our mother would also extend to aunties and uncles as well as to other entities in the environment, such as sky, lake, turtle, and basalt, to help us in times of need. What is felt by one sends ripples through us all: our triumphs and failures, our progresses and pain. For this work, Watt thought: “What would it look like if we were all companion species?” Hearing Gaye’s song again as an adult made her look deeper into the history of the lyrics—when it was written and what was going on at the time—and compare it to our contemporary political unrest. This investigation led to the creation of Companion Species (Speech Bubble).

This monumental work, suspended from the ceiling, reaches a height of over eleven feet and is more than sixteen-feet wide. It is made from a patchwork of rectangles cut from wool blankets of varying sizes and shades of red. On each fragment, a word or series of words (many of them lyrics from Marvin Gaye’s 1969 song), is hand stitched in embroidery floss using various fonts. Across the broad surface and linking all the individual text together are the hand-stitched words, “Mother Mother,” iconic lyrics from Gaye’s song.

Embroidered words (detail), Marie Watt, Companion Species (Speech Bubble), 2019, reclaimed wool blankets, embroidery floss, and thread, 136 5/8 x 198 1/2 inches (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville; photo: Edward C. Robison III) © Marie Watt

Like a vinyl record, there are two sides to Companion Species (Speech Bubble), and like a record album, the work holds a collection of stories that come together into one. In addition to lyrics from Gaye’s song, other words embroidered on the fabric (like “Auntie,” “Uncle,” “Ancestor,” and “Elder”) come from Watt’s stream of consciousness as she thought of Seneca, Haudenosaunee, and other Indigenous ways of acknowledging our relatedness. The words serve as prompts for storytelling and remembering our connectedness. This work is connected to the importance of oral history and the importance of remembering stories, sharing them, and passing them on to others. Watt’s hope is that we can learn from the stories and histories of those who came before us and do better for future generations.

“B side” (back), Marie Watt, Companion Species (Speech Bubble), 2019, reclaimed wool blankets, embroidery floss, and thread, 136 5/8 x 198 1/2 inches (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville; photo: Edward C. Robison III) © Marie Watt

Sewing circles

Shared experiences and communication are at the core of Marie Watt’s practice as an artist. Like many of her works, Companion Species (Speech Bubble) was created by community sewing circles that took place across the country. Woolen blankets, cut into various sizes, were sewn together into this larger whole, and were then hand embroidered with text on both sides. For the sewing circles, Watt provides the materials and the settings, and with the help of hosting institutions invites members of these disparate communities to gather together, to share stories and learn about one another as they sew. All ages, genders, and races are welcome to the sewing circles and no sewing experience is required.

Like other forms of community organizing, such as protest marches, individual voices contribute to a larger message and movement in Watt’s sewing circles. Each person’s stitch is unique—like a fingerprint or a signature, while contributing to a larger collective message. Words that are written (or stitched in this case) by hand produce something unique which cannot be reproduced mechanically. Making the work large amplifies the strength of the voices present at the sewing circles. These gatherings are often cross-generational and multicultural. For Watt, such collaborations mimic an Indigenous way of teaching and learning that predates non-Native academic institutions. Having people from different cultures, generations, and life experiences collaborate honors the idea that we all have knowledge to teach and learn and stands in contrast to formal classroom education or solitary research. The sewing circles aren’t a means to an end. The ultimate goal is to connect with neighbors, strangers, and with oneself.

Blankets

Watt is drawn to blankets because of how they were used in her family and in the larger Seneca community. Similar to other tribes in the Pacific Northwest, Seneca families give blankets away to honor people for being witnesses to important life events such as births, weddings, or returning from war. In this tradition it is as meaningful to give a blanket away as it is to receive one, and each blanket is a carrier of meaning and a story. Watt was drawn to the cultural specificity that she associates with blankets, but also to how blankets’ histories can cross cultures and languages. As Watt says, blankets have culturally specific connections for her and her community, but blankets are part of universal experiences. For example, babies are often received in blankets at birth and it is common to depart this life in a blanket. In between these bookends, our days begin and end within these pieces of cloth, and our bodies and stories are imprinted on them.

The function of scale in Companion Species (Speech Bubble) is to start with blankets, which are familiar and intimate, and through the process of sewing them together and embroidering words onto them, to create a work that can be experienced collectively. When installed, this work hangs away from a wall, which allows for a sense of sound and movement when a body walks past it or when air blows through the space. The shape of this object may reference a megaphone, a tongue, or a speech bubble. In a speech bubble, words are projected into a physical space or onto a page. Watt connects this idea to the concept of call-and-response: projecting words back to our ancestors, and forwards towards future generations.

Embroidered words (detail), Marie Watt, Companion Species (Speech Bubble), 2019, reclaimed wool blankets, embroidery floss, and thread, 136 5/8 x 198 1/2 inches (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville; photo: Edward C. Robison III) © Marie Watt

Companion species

Watt often thinks about how she understands her relationship to others, including animals and the environment, and where that understanding comes from. In her case, this understanding comes from the Seneca and Haudenosaunee creation story in which Skywoman falls (some say was pushed), through a hole in the Skyworld. As she falls, she is first assisted by birds, and then as she lands, by animals on what we now refer to as Turtle Island (North America). Because of the way animals helped Skywoman, they are considered the First Teachers. Seneca clans are represented by animals, and Watt is from the Turtle Clan. These clans acknowledge this historic relationship with animals and, by extension, the environment. So, for her, the concept of companion species addresses not only an interrelatedness to other humans, but also to animals and entities like air, water, and soil.

This idea of companion species led Watt to consider, what might be a successful entry point for Anglo-Europeans to understand how we are connected to other living beings? In European culture, it seemed to Watt that she could start with people’s relationship with their pets. She decided to begin with humans’ relationships with dogs and began doing research in world literature and oral traditions. She was struck by a print and a sculpture of the Capitoline Wolf in which the she-wolf’s body is sheltering Remus and Romulus, the legendary founders of ancient Rome. The fact that the wolf is not the biological mother but is mothering them impacted her. She was moved by how the wolf is emaciated yet nourishes the healthy and robust-looking babies and how she uses her body as a canopy to shelter them. The wolf has bags under her eyes, yet could still ferociously protect the vulnerable children.

Capitoline Wolf, 5th century B.C.E. or medieval, bronze, 75 cm high (Capitoline Museums, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Watt comes from a matrilineal custom (a system of kinship and descent traced through female family lines, as opposed to patrilineal systems used in most Anglo-European cultures that trace descent through male lines) and in looking at this mothering canine began to think about the attributes of “motherhood,” leading her to consider how all humans have mothering characteristics and, perhaps in this historical moment, how important it is for us to summon these characteristics as we steward the environment and our relationships moving forward. As noted by the Crystal Bridges Museum, in the case of Marvin Gaye and Watt’s own use of the repeated words, “familial terms like ‘mother’ and ‘brother’ are not used solely to indicate biological awareness, but to extend to all humans, and in Iroquois teaching, to animals and the environment as well.”

Embroidered words (detail), Marie Watt, Companion Species (Speech Bubble), 2019, reclaimed wool blankets, embroidery floss, and thread, 136 5/8 x 198 1/2 inches (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville; photo: Edward C. Robison III) © Marie Watt

Connection to one another and awareness of one’s impact on others is important, both to Companion Species (Speech Bubble), as well as Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” This song was responding to socio-political movements in the late 1960s and early 1970s, such as the Civil Rights movement, the occupation of Alcatraz Island by Indigenous activists who sought to reclaim the island for a cultural and educational center, the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Vietnam war. These movements shed light on the need and desire for change in American society and of shared experiences of trauma—to minds, bodies, and the environment around us. Gaye’s song evoked the emotional feeling of that time, while invoking the call-and-response so often tied to social movements through a specific question: “What’s going on (what’s going on)?” More recently, when Watt was struck by this song a water crisis was unfolding in Flint, Michigan, Water Protectors on the Standing Rock reservation in the Dakotas were protecting clean water from the construction of an oil pipeline, and the Black Lives Matter movement was growing in strength. If ever there was a time for us to come together, it is now. Conversations between part and whole, between individual and community, are at the core of Watt’s work. In Companion Species (Speech Bubble) many hands came together in common purpose and in collaboration, inspired by the past with the goal to realize a better future.