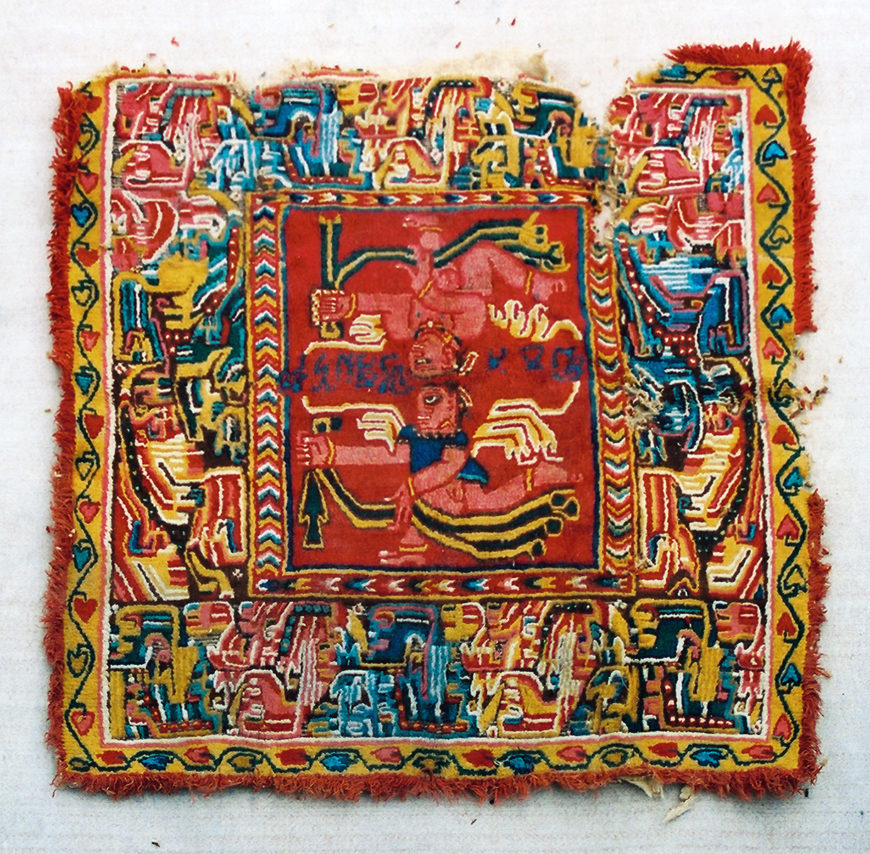

Knotted Carpet with human figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, 5th–6th century C.E., Shanpula Township, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (photo: Qi Xiaoshan)

Imagine a carpet being as valuable as gold. At Khotan, one location in western China on the ancient global trading network known as the Silk Roads, high-quality carpets made of wool became luxurious trade items. One brightly colored 5th–6th century knotted carpet was made from wool to cover a bed or floor. The carpet depicts human figures, trees, and includes an inscription woven in between (images below). The border offers decorative motifs, stylized animal forms, and wave motifs. Due to the dry climate in this region, the amazingly bright colors and much of the wool are naturally preserved despite the passage of 1,500 years.

Carpets like this one reveal how multiple cultural ideas, art traditions, and aesthetic tastes—from India, Bactria, the Hellenistic world, the early Roman Empire, and Persia (Achaemenid and Sasanian)—informed objects made and traded on the ancient Silk Road.

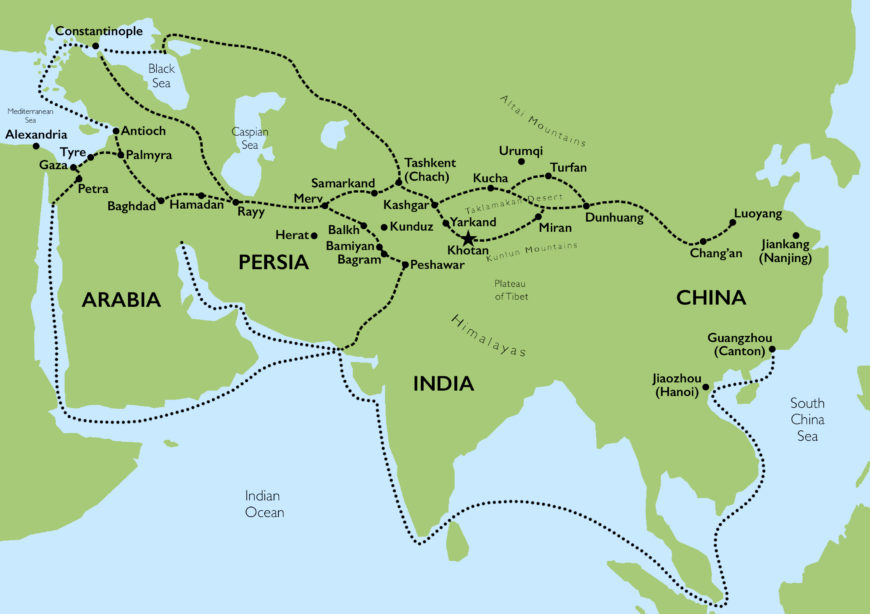

Map showing Khotan (near center) in the network of trade routes that made up the Silk Roads (adapted from a map by Dr. Evan Freeman, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Silk Road

The Silk Road is a romantic term given by some Europeans of the late 19th and early 20th centuries to describe an ancient global trading network that extended from East Asia to Europe (for example, from China to Rome), from about 1000 B.C.E. (or earlier) to early modern times. Despite its name, it was not a single road, and the merchandise traded included far more than silk. Trade along these roads included spices, precious stones, jewelry, glass, textiles, exotic plants and animals, and much more. This large network was connected via caravan posts in numerous small oases that made it possible to traverse vast deserts, mountains, and other types of harsh terrain, and via ships over the rivers and seas.

A single trader would not likely travel the entire route (except for some diplomats or individuals like the Venetian explorer and merchant Marco Polo). Most traders would exchange their merchandise at certain posts on the borders with other countries or territories. An object—such as a bolt of silk—would go through several or many hands like a relay race before it arrived at the end-users.

China kept silk-making a secret for many centuries, so the silk trade is almost all from China to other places. However, besides the trade of luxurious Chinese silk, other textile materials were traded extensively and in multiple directions across trading networks. Woolen textiles from Hellenistic and Roman-ruled Syria from places like Palmyra and Dura-Europos), and cotton cloth from India have been discovered in many oasis towns in the Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang, a western region of China, where the knotted carpets in question are found.

Ideas about politics, philosophy, religion, technology, art making, and aesthetics became integrated as a result of trade and military campaigns between empires (such as Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Persian Empire and the Chinese Han Dynasty’s expansion to the western region and Central Asia). Cultural exchange and integration took place on a near global scale, and has proven to be the most significant impact of the Silk Road.

Knotted carpets in Central Asia

Carpets could be made in different ways. A knotted carpet, like the one above, was made by weaving the wool yarn with extra yarn threads piled up on warps to produce a thicker and fluffier surface.

Carpet fragments from Yanghai, Xinjiang, China, 1000–700 B.C.E.

The earliest wool knotted carpets known are from the western region of China, dated to 1000–700 B.C.E. and the Altai region of Russia, dated to 500–400 B.C.E. [3] More carpets, dated from 200 B.C.E. to 600 C.E., have been discovered in many sites in Xinjiang (including Khotan) and some sites in northern Afghanistan. They include plain ones and colorful ones with geometric patterns and natural representations. Among these peoples and places, Khotan in west China developed into a renowned carpet-making center.

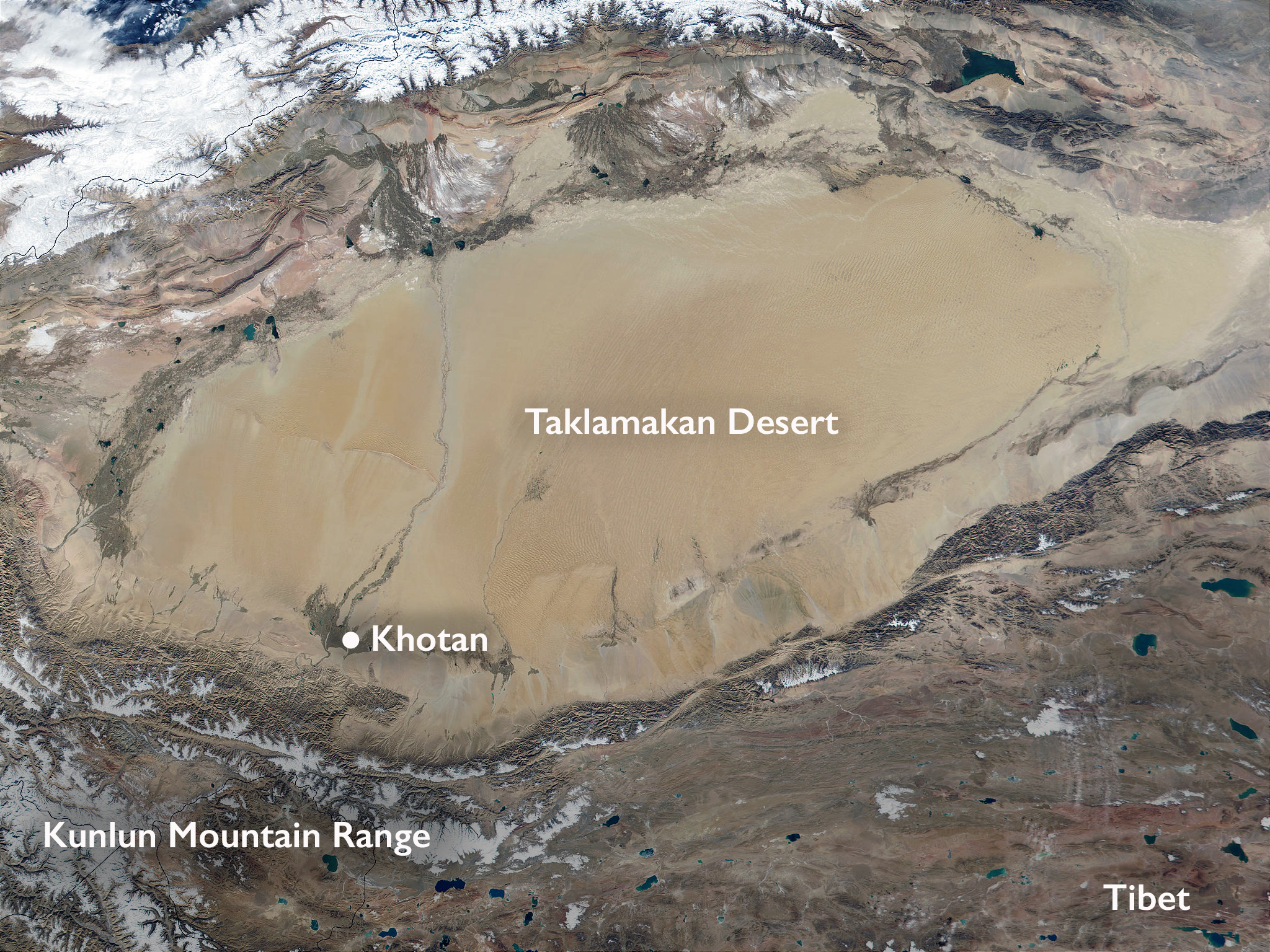

Khotan and Khotani carpet

Khotan is an oasis town on the southern edge of the world’s second largest desert, the Taklamakan Desert. Two seasonal rivers Yurumkash (White Jade) and Karakash (Black Jade) from the Kunlun Mountains nourished this large oasis for millions of years, making it suitable for people to live. It was also an important station for caravan traders and other travelers from either the east or west to rest during their long distance journey. The diverse population included Sakas, Gandhari Prakrit Indians, Khotanese-Sakas, Chinese, Tibetan, and Turkic groups.

At the crossroads of the Silk Road, Khotan developed into a significant center of culture and commerce. Multiple religions were practiced in Khotan, including Shamanism, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Brahmanism (Hinduism), Manicheanism, Christianity, and possibly Judaism. [4] Several well-known historic people visited Khotan—such as Chinese General Ban Chao, monks Fa Xian, Song Yun , Xuan Zang, and Marco Polo and his father and uncle, who traveled from Venice, Italy, to Beijing, China.

Even though silk had to be imported from central China at first, in the 5th century C.E. it appears that the Khotanese learned the secret of silk making. Supposedly, the king married a Chinese princess (described by Xuan Zang in his 7th-century diary), who had smuggled silkworm eggs into Khotan in her hair. Long before the arrival of silk, however, Khotan had already made its fame with carpets, known as “Khotani Carpets.” In surviving documents, Khotan carpets appear as either gifts or commercial payment that could even replace gold. The immense value of these carpets is even noted in one document from c. 235–325 C.E.:

On another occasion, the queen came here. She asked for one golden stater (coin). There is no gold. Instead of it we gave tavastaga (knotted carpet), thirteen hands long. Seraka took it. Many people here know this matter as witnesses. . . .[5]

King and Queen of Khotan standing on carpets, reconstructed painting of Dunhuang Cave 98, east wall, Five Dynasties, 907–60 C.E.

Khotan’s renown as a carpet-making center is indicated in depictions of the Khotanese. For instance, in paintings from Dunhuang—a famous Buddhist site east of Khotan in Gansu province, where there are about five hundred rock-cut caves full of mural paintings—the king and queen of the Khotan were painted standing on carpets. Most of Khotani carpets were originally used to cover beds, floors, and seats.

Dancers and musicians on a carpet, detail of a palace scene. Dunhuang Cave 156, north wall, late Tang, 827–59 C.E.

We also see dancers and musicians dancing and sitting on carpets (such as in Dunhuang Cave 156) in numerous scenes. The designs of these painted carpets match actual carpets found in Khotan and the rest of Xinjiang.

Three of the five carpets looted from Shanpula Township. Left: carpet with putti figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, Shanpula, 5th–6th century; center: knotted wool carpet, 5th or 6th century, Shanpula; right: carpet with putti figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, Shanpula, 5th–6th century (photos: Qi Xiaoshan)

A group of carpets

In 2008, a group of seven carpets, all dated 5th–6th century C.E., was looted from Shanpula Township (Luopu County, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China). Five of them were caught from the looters, including the one that is the focus of this essay.

The carpets are the first known examples of human figures set within natural features and in a narrative in the history of Khotan carpets. The complexity of the design and bright colors make them very rare cases in the world history of knotted carpets of this early time.

Another carpet that survived looters’ hands. Carpet with putti figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, Shanpula, 5th-6th century C.E. (photo: Qi Xiaoshan)

As a group, the five knotted carpets tell us a great deal about the shared cultural ideas and traditions in Khotan. They all have striking, bright colors with a unique figurative and naturalistic style (versus the earlier geometric style in Xinjiang carpets), each with rich border designs composed of flowers and leaves, waves, animals, and some unidentified motifs. Four of the five carpets have Khotan-Saka inscriptions woven into them—such as the carpet that opens this essay. The inscription is puzzling: while it is based on Indian Brahmin scripts, it represents Khotanese language, an ancient eastern Iranian language.

Left: Knotted Carpet with human figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, 5th-6th century CE; Shanpula Township, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (photo: Qi Xiaoshan); right: line drawing of the Knotted Carpet

Let’s focus on this carpet in more detail. It is in relatively complete condition, with relatively minimal damage given its age, which helps us to identify images and their narrative relationships. In the center portion of the carpet, we see human figures arranged in seven horizontal rows. Nearly all are shown in a three-quarter view and characterized by prominent eyes and noses and naturalistic bodily proportions.

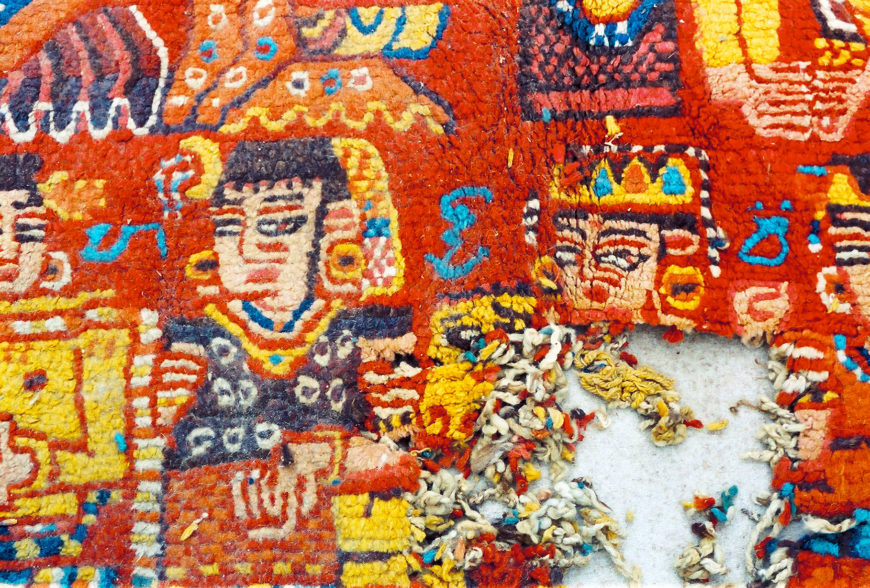

Detail of several figures, with the Brahmi script between them in bright blue. Knotted Carpet, detail of two human figures, 5th–6th century C.E., Shanpula Township, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (photo: Qi Xiaoshan)

If a particular body part does not contrast sufficiently from the red background, it is carefully set off by a thin contour line of contrasting color—black, blue, or yellow; otherwise, red is generally used. In many areas, especially faces, arms, and legs, a light red or pink line is added within the outer contour line as if to suggest some form of modeling or shading. The skin tone of most figures is pinkish. Hands and feet appear unusually large; the individual fingers are carefully shown and all feet are bare.

Blue Krishna in Lila Dance, detail of Knotted Carpet with human figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, 5th–6th century C.E., Shanpula Township, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (photo: He Zhang)

Who are the figures?

Although the carpet was found in China, its subject matter and motifs share more in common with art from South Asia and Central Asia. For example, there is a small figure in dark blue, who appears twice in the composition and is reminiscent of an Indian deity, Krishna, who often appears in blue color in Hindu art. Krishna, whose name means “dark” or “dark blue” in Sanskrit, and appears in Hindu epics such as Mahabharata, Harivamsa, and Bhagavata Purana.

Detail with two figures, possibly showing Yashoda sitting in Indian royal posture lalitāsana, and the little blue Krishna holding a butter ball motif in the right hand. Knotted Carpet with human figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, 5th–6th century C.E., Shanpula Township, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (photo: He Zhang)

In the carpet, the small blue figure appears twice among people of all ages and genders—male and female, old and young.

Figures also appear to wear Indian dress in the trees, water, hills, which provide landscape settings for Krishna’s youthful life as herdsman in the countryside. In one scene, we see a figure sitting in Indian royal posture (lalitāsana) and the little blue figure holding a ball-shaped motif in the right hand. This is likely supposed to relay the story of how, as he grew up, Krishna was mischievous, stealing butter from his mother Yashoda, a gopi (cowherd woman), and the other gopis to feed monkeys. In another scene, the blue figure is between two gopi girls, one is playing flute and the other is reaching out her hand to another young man as if dancing, which suggests a typical Lila dance in the Krishna stories.

The appearance of the Krishna story makes the carpet significant in two ways. First, it provides evidence of Hindu imagery early on in Khotan. Also, it is the earliest example of Krishna in blue color—almost one thousand years before the next existing image of a blue Krishna appears in Indian art. Incorporating Hindu imagery reveals the transmission of ideas and art along the Silk Road—so too does the carpet’s style.

The carpet’s style

The design of the carpet shows several artistic styles and motifs from different cultures on the vast trading network. We see a number of visual elements that borrow from Indian stories and art, as noted above. Besides Krishna, we see figures in Indian dress (such as dhoti), sitting in specific royal postures, and conducting Hindu rituals (such as the aarti fire ritual).

Detail of a man in baggy trousers, holding a lamp and conducting an aarti. Knotted Carpet with human figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, 5th–6th century C.E., Shanpula Township, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (photo: Qi Xiaoshan)

Visual motifs from Central Asia are also apparent. For example, some male figures wear long tunics with a waist belt or baggy trousers, which are typical of Central Asian dresses seen with the Kushans—a nomadic people who ruled Central Asia and northern India in the first few centuries C.E.

Left: Seated figure, detail of a second carpet from the same hoard with the similar design as the main carpet in this essay; the same figure in the main carpet is damaged. Pay attention to the sitting posture and border design of running waves in the carpet and the Greek vase. Knotted Carpet with human figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, 5th–6th century C.E., Shanpula Township, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (photo: Qi Xiaoshan); right: Bell-krater (mixing bowl) with seated male figure and running wave motif, c. 350–325 B.C.E., attributed to Python, terracotta, Greek, South Italian, Paestan, 30.7 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

There are also a number of Greco-Roman and Bactrian influences. For instance, the natural and free manner of representing human figures and landscapes with natural body movements and postures is similar to figures on many Greek vases and Greco-Roman mosaics. The carpet figures’ faces also are often shown in a three-quarter profile, which is also a Mediterranean tradition. Likewise, the wave motifs in the carpet’s narrow borders also borrow from Greco-Roman art.

A carpet at the crossroads

Knotted Carpet with human figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, 5th–6th century C.E., Shanpula Township, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (photo: Qi Xiaoshan)

This carpet indicates that the knowledge, art making technique, and aesthetic taste traveled with the materials to many places of the world and were willingly accepted and blended by local peoples of different places, like those of Khotan. The carpet showcases the cultural interaction and integration happening at the crossroads of East and Central Asia, South Asia, and China in the 5th–6th century on the ancient Silk Road.

Notes:

[1] There are several ways to tie or knot the yarn piles on the surface of a carpet: symmetrical, asymmetrical, and single-warp or U-shape.

[2] Knotted carpets appear as early as 1500 B.C.E. in Egypt, but with linen fiber, including examples discovered in the tombs of individuals related to Hatshepsut, Queen and Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom.

[3] The earliest samples are the ones excavated in Yanghai (1000–700 B.C.E.), Xinjiang, China, and then Pazyryk (500–400 B.C.E.), Russia.

[4] There is a Persian Jew’s letter of the 8th century C.E. discovered in a nearby site (Dandan-Uiliq). Many Confucian texts in Chinese were found as well.

[5] Burrow, T. A Translation of the Kharoṣṭhi Documents from Chinese Turkistan. London: The Royal Asiatic Society, 1940, Document number 431–2. Online access: https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/niyadocts.html, accessed on June 5, 2022.

Additional resources

Bailey, H. W. Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Banerjee, P. Life of Krishna in Indian Art. New Delhi: National Museum, 1978.

Burrow, T. A Translation of the Kharoṣṭhi Documents from Chinese Turkistan. London: The Royal Asiatic Society, 1940.

Duan, Qing: “The Inscriptions on the Sampul Carpets.” Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology 5/2010, Brepols, Belgium.

Duàn Wénjié(Editor-in-Chief: Zhōngguó Dūnhuáng bìhuà quánjí 段文杰(主编:《中国敦煌壁画全集》 (第五、六、七、八、九集,天津人民美术出版社,2006 [Complete Collection of China Dunhuang Murals; vols.5, 6, 7, 8, 9; Tianjin People’s Art Publisher]

Hétián wénguǎnsuŏ biānzhù: Yútián. Xinjiang měishù shèyĭng chūbǎnshè 和田文管所编著,新疆美术摄影出版社2004 [Hetian/Khotan Administration Office of Cultural Relics (edited) : Khotan. Xinjiang Fine Art and Photography Press 2004]

Jiǎ Yìngyí: Xīnjiāng gŭdài máozhīpĭn yánjīu 贾应逸《新疆古代毛织品研究》上海古籍出版社 2015 [Studies on the Woolen Textiles in Ancient Xinjiang, Shanghai Archives Publisher 2015].

Jiǎ Yìngyí 贾应逸 Lĭ Wényīng 李文瑛, Zhāng Hēngdé 张亨德. Xīnjiāng dìtǎn 新疆地毯 [Xinjiang Carpets]. Suzhou daxue chubanshe 苏州大学出版社 Suzhou University Press, 2009.

Schmidt-Colinet, Andreas. Die Textilien aus Palmyra: Neue und alte Funde (Damaszener Forschungen), P. von Zabern, 2000

Spuhler, Friedrich. Pre-Islamic Carpets and Textiles from Eastern Lands. Dar al-Arhar al-Islamiyyah the al-Sabah Collection Kuwait. Thames &Hudson, 2015.

Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Museum and Xinjiang Institute of Archaeology. Shanpula in Xinjiang of China – Revelation and Study of Ancient Khotan Civilization. Xijiang People’s Publishing House, 2001. 新疆维吾尔自治区博物馆,新疆文物考古研究所编著:《中国新疆山普拉-古代于阗文明的揭示与研究》,新疆人民出版社2001

Yuè Fēng: Xinjiang lìshĭ wénmíng jícuì. Xinjiang wénwù guǎnlĭjú, Xinjiang měishù shèyĭng chūbǎnshè 2009 岳峰:《新疆历史文明集萃》新疆文物管理局,新疆美术摄影出版社 2009 [The Best Collections of Xinjiang History and Civilization. Xinjiang Cultural Relics Bureau, Xinjiang Arts and Photography Publisher, 2009].

Zhang, He. “Figurative and Inscribed Carpets from Shanpula-Khotan: Unexpected Representations of the Hindu God Krishna A Preliminary Study.” Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology 5/2010: pp. 59–73.

Zhang, He. “The Terminology for Carpets in Ancient Central Asia” in Sino-Platonic Papers May 2015, University of Pennsylvania.

Zhang, He. “Stein’s Taklamakan Carpet Finds and New Discoveries in Xinjiang—Issues Concerning Knotting Techniques and Their Cultural Associations.” Proceedings for International Conference on “Marc Aurel Stein with special reference to South and Central Asian Legacy: Recent Discoveries and Research” Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New Delhi, India. 2017.

Zhang, He. “The Terminology of Central Asian Carpet” in the Journal of Dunhuang Research, no. 4, 2018 by the Dunhuang Research Academy, Dunhuang, China.

Zhang, He. “Knotted Carpets from the Taklamakan: A Medium of Ideological and Aesthetic Exchange on the Silk Road, 700 BCE–700 CE.”The Silk Road Journal, the Silk Road House 2020/03

Zhang, He. “Ancient Questions” and “A Single-warp Knotted Carpets” in Hali magazine, Winter 2020, issue 206, London.