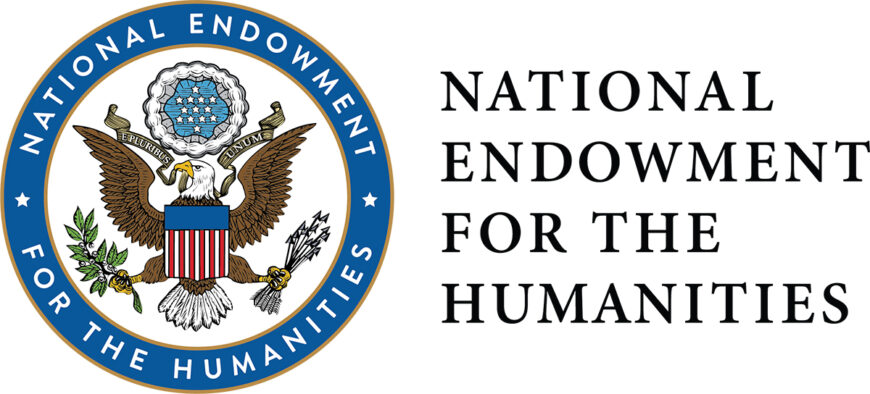

Bernardino d’Asti, The Missionary Gives his Blessing to the Local Ruler during Sangamento, c. 1750, watercolor on paper, 19.5 x 28 cm (Biblioteca Civica Centrale, Turin, MS 457, folio 12 recto)

A watercolor painted around 1750 features an elite man from the Kingdom of Kongo, dressed with a red cloak and loincloth kneeling in front of a Christian church as a European friar performs a gesture of blessing. Behind him, warriors dance and people play music with a marimba (a percussion instrument made of gourd and thin wood planks), drums, and ivory trumpets made from elephant tusks, bringing sound to the event. The watercolor, painted by a Christian (Franciscan) missionary, showcases one of the Kingdom’s most important political ceremonies, called sangamento.

Map of the Kingdom of Kongo c. 1650 with the outlines of modern countries, adapted from John K. Thornton, A History of West Central Africa to 1850 (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2020), p. x (underlying map © Google)

During sangamento, the elite of the Kingdom of Kongo, who, together with their kings had voluntarily converted to Catholicism around 1500 (after being introduced to the religion by Portuguese explorers), demonstrated in a danced ritual their allegiance to both their king and to the Catholic Church. Sangamento was performed on special occasions, such as on feast days or before going into battle. The choreography, clothing, and symbolism of sangamento mixed European and Kongo elements together in a unique Afro-Catholic performance. There, objects as well as political and spiritual practices that were once solely European and once solely central African, came together into a new whole: Kongo Christianity.

Syncretism

Scholars have called this process of combining two (or more) different religious traditions “syncretism.” [1] Through the trans-Atlantic slave trade (begun in the 15th century by the Portuguese), elements of central African syncretic religions, such as Kongo Christianity, were brought to places like Brazil, which received nearly half of all of the enslaved Africans abducted and transported across the Atlantic. Many enslaved Africans who were brought to the western hemisphere were taken from communities in the Kingdom of Kongo or neighboring areas such as Angola in west-central Africa and would have been familiar with Kongo Christianity. Other syncretic religions developed as a result of the slave trade, such as Haitian vaudou, and scholars now recognize that more modes of Afro-Atlantic spirituality developed and continue to exist in the Americas and in Europe today.

Carlos Julião, “Black King Festival,” last quarter of the 18th century (Brazil), watercolor on paper, in Riscos illuminados de figurinhos de brancos e negros dos uzos do Rio de Janeiro e Serro do Frio, Iconografia (C.I.2.8 in the collections of the Fundação Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro)

Brazilian Congadas

Just a few decades after the watercolor of sangamento being performed in Kongo was painted, an officer in the Portuguese army named Carlos Julião created a series of images depicting men, women, and children of African origins or descent participating in a festival in Brazil. Julião had worked in many areas that were at the time under the colonial control of Portugal. In this painting, Julião pictures a Black king wearing a European-style crown, splendid clothes, and holding a golden scepter in his hand. He walks under a large umbrella to the sound of musical instruments, attended by two servants in uniforms. Though Julião did not give titles to his painting, scholars have recognized the event as part of celebrations within a community of Africans and Afro-descendants surrounding the coronation of their elected king and queen. These celebrations, called Congadas or Congados in Brazil, hark back to sangamento in the Kingdom of Kongo, and continue to take place in 21st-century Brazil. The colorful wraps around the lower bodies of the male figures, the feathered headdresses, the flags, and the instruments, such as the marimba and box scratcher held high by the man in blue cloth in Julião’s image, are all elements with parallels in the Kongo, pointing to the specific Central African dimension of this performance.

At the time Julião made this work, the men, women, and children depicted lived in Brazil within a slave society, an environment in which their African origins placed them at the bottom of the social hierarchies, whether they were enslaved or free. Yet, even in this social position, they planned and staged elaborate celebrations through which they claimed small but resonant spaces of freedom and resistance to enslavement and disenfranchisement through the coronation of their own kings and queens. Other regions of the Americas practiced (and some continue to practice) similar ceremonies, though with different names, including San Juan Congo in Venezuela, and Pinkster in 19th-century North America. [2]

This 18th-century watercolor therefore illustrates one version of an event with deep historical roots and broad geographic reach. Situated in areas under the control of different European colonial empires and in varied linguistic environments, the Black kings festivals share common origins in the desire from members of Afro-descendant populations to organize festive occasions and to create communities on their own terms.

Black confraternities and Black saints

Beginning in the 15th century, other Black communities came together for common purpose. A dozen years after the Portuguese arrived in the Kingdom of Kongo and two years after ships sailing under the patronage of the Spanish crown landed in the Caribbean, the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas sanctioned Spain and Portugal’s claims over lands they “discovered” beyond Europe with the support of the Pope in Rome (“discovered” is used here with quotation marks because while it was the term Europeans long used to characterize their arrival in the Americas, the word does not accurately describe the event from the perspective of the region’s Indigenous populations). The Treaty of Tordesillas mandated that the Spanish and Portuguese convert the inhabitants of those lands to Catholicism. This would include the Indigenous populations as well as the enslaved Africans who would soon arrive in the Americas chiefly through the Atlantic slave trade.

Under these conditions, African men and women living free or enslaved in Europe and the Americas organized into religious communities known as confraternities or sodalities. [3] Members of these associations adhered to a set of rules, paid dues, and obeyed internal hierarchies. The principal aim of the confraternities was to organize members’ worship within the Church and their social life outside of it with a special emphasis given on burial rites considered of crucial importance for the deceased’s ability to secure the eternal life Christianity promised to the devout. The organizations could be exclusive to a particular gender, racial identity, or enslavement status.

Unidentified Afro-Brazilian artists, St. Antonio de Catagerona, 18th century (Brazil), watercolor, “Compromiso da Irmandade de S. Antonio de Catagerona” (Oliveira Lima Library, Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.)

The confraternities also commissioned artworks dedicated to saints which they displayed on the altars or in the churches they built through the sometimes considerable donations collected by and from their members. [4] Images of Black saints featured prominently in such spaces, as saints would be called upon to assist in both earthly and heavenly matters. For example, one of the brothers of the Brazilian Black Confraternity dedicated to Saint Antonio de Catagerona, (sometimes called Saint Antonio da Noto), illustrated the most important document of the association (its compromisso, or set of rules), with a watercolor image of the saint. [5] Here, Saint Antonio de Catagerona, who was born in North Africa and enslaved as a youth, is shown cradling the Christ child in his right arm. The vibrant depiction displays the intimate bond between a Black saint, in whose likeness the brothers could easily recognize themselves, and Jesus. It also serves as an image for the closeness between the brothers of the confraternity, God, and the Catholic Church. Other popular patron saints of Black confraternities in the era of trans-Atlantic slave trade were the Virgin Mary or saints associated through their biographies to Africa such as Saint Benedict of Palermo, born in Sicily of enslaved African parents, and Saint Iphigenia, an Ethiopian princess. [6]

Haitian Vodun

Elsewhere in the Black Atlantic, images of Catholic saints played a very different role in the spiritual practices of African and Afro-descendant devotees. Vodun, also known as vaudou, is a religion with roots in the Bay of Benin in west Africa in today’s countries of Benin and Togo (a region which also saw large numbers of people enslaved and transported to the Americas). Initiates of Vodun, which has branches stretching all around the Atlantic world, including in Haiti, also uses images of Catholic saints in their devotions, but recognize in those images non-Christian spirits and deities.

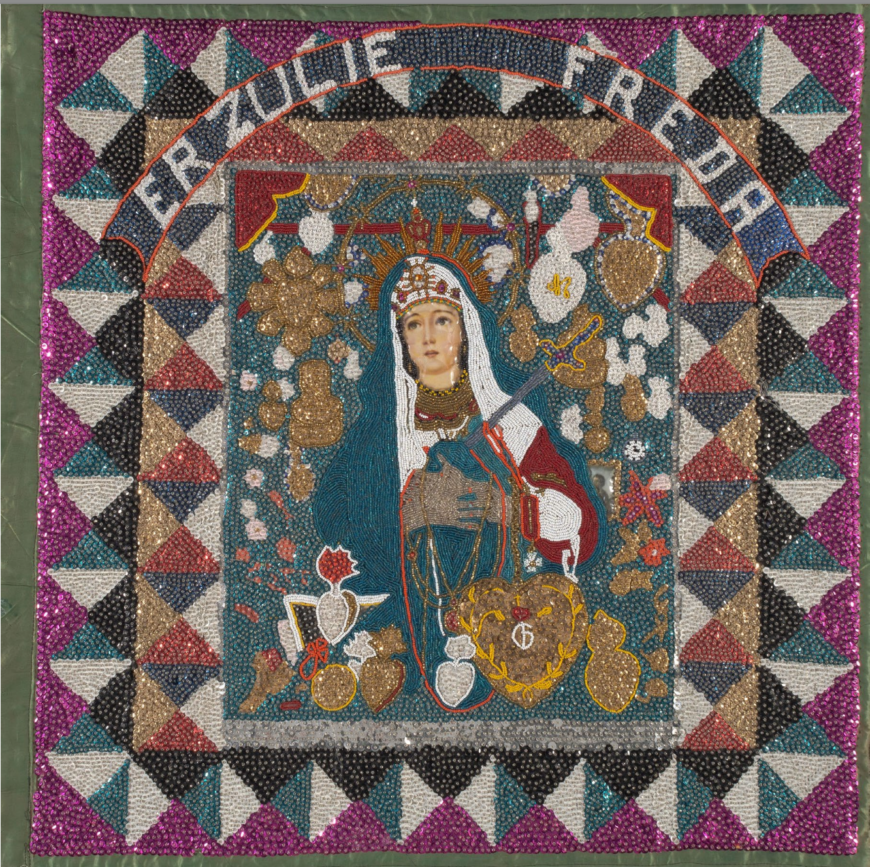

For example, Haitian vaudou devotees have found their deity Ezili Freda, the patroness of love and the fine things in life, in images of the Catholic Virgin of Sorrows, where Mary, the mother of Christ, is richly dressed as the queen of Heaven and dramatically holds her chest which is pierced with a sword (a symbol of the pain she suffered with the death of her son, Jesus, on the cross). [7] The brilliant crown, jewels, and flowing textiles of the dramatically pictured, beautiful woman in Catholic imagery lead vaudou devotees to recognize her as Ezili Freda, and vaudou artists to recreate the image in materials enhancing further her divine brilliance, such as the shimmering sequins and beads of a contemporary vaudou flag made by a Haitian artist from the city of Jacmel.

Artist from Jacmel (Haitian, 1950–85), Vaudou Flag, 1975–85, sequins and beads on burlap, satin backed, 81.28 x 80.01 cm (Accession Number 1999.031.002, previously Snite Museum of Art, now in the collection of the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art, Notre Dame)

Afro-Atlantic spirituality

The golden crown and scepter catching the light in the grand gestures of a Black king in 18th-century Brazil or the brilliant sequins manifesting the presence of a vaudou goddess in the guise of the Virgin Mary in 20th-century Haiti are two among the myriad visual testaments to the endurance and dynamism of Afro-Atlantic spirituality in its many forms. Syncretic religions, like Haitian vaudou, and Afro-Catholic rituals, such as Brazilian Congadas, are two parallel paths through which African spirituality found new expressions in the Americas, on the other side of the Middle Passage and despite the enduring, multivalent violence of enslavement and its aftermaths.

Even in the context of forced migration, life in enslavement, forced spiritual and cultural conversion, the history of African American religiosity is one of resilience, resistance, and creativity, as evidenced in Black confraternities on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. These examples are eloquent witnesses to the prismatic creativity of Afro-Atlantic spirituality from the era of the Atlantic slave trade to today.

Notes:

[1] Melville J. Herskovits, The myth of the Negro past (New York: Harper, 1941). Melville J. Herskovits, “African gods and Catholic saints in New World Negro belief,” American Anthropologist, volume 39, number 4 (1937); Arthur Ramos, “As culturas negras no novo mundo,” Bibliotheca de divulgação scientifica, sob a direcção de Arthur Ramos (Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1937).

[2] David M. Guss, “the selling of San Juan: the performance of history in an Afro‐Venezuelan community,” American Ethnologist, volume 20, number 3 (1993); Mesi Walton, “Afro-Venezuelan Cultural Survival: Invoking Ancestral Memory,” Middle Atlantic Review of Latin American Studies, volume 4, number 2 (2020); Jesús García, La Diaspora de los kongos en las Américas y los Caribes (Caracas: Dirección de Desarrollo Regional de la Fundación Afroamericana: Editorial APICUM: UNESCO, 1995), Government publication (gpb); International government publication (igp).

[3] Elizabeth W. Kiddy, Blacks of the Rosary: Memory and History in Minas Gerais, Brazil (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005). Jeroen Dewulf, “Pinkster: An Atlantic Creole Festival in a Dutch-American Context,” Journal of American Folklore, volume 126, number 501 (2013). Miguel Valerio, Sovereign Joy (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

[4] Miguel A. Valerio, “Architects of their own humanity: race, devotion, and artistic agency in Afro-Brazilian confraternal churches in eighteenth-century Salvador and Ouro Preto,” Colonial Latin American Review, volume 30, number 2 (2021).

[5] Erin Kathleen Rowe, Black Saints in Early Modern Global Catholicism (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2019), pp. 145–46.

[6] Rowe (2019).

[7] Dana Rush, “Eternal Potential: Chromolithographs in Vodunland,” African Arts, volume 32, number 4 (winter 1999).

Additional resources

Jeroen Dewulf, “Pinkster: An Atlantic Creole Festival in a Dutch-American Context,” Journal of American Folklore, volume 126, number 501 (2013), pp. 245–71.

Cécile Fromont, “Dance, Image, Myth, and Conversion in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1500–1800,” African Arts, volume 44, number 4 (2011), pp. 52–63.

Jesús García, La Diaspora De Los Kongos En Las Américas Y Los Caribes (Caracas: Dirección de Desarrollo Regional de la Fundación Afroamericana: Editorial APICUM: UNESCO, 1995).

David M. Guss, “The Selling of San Juan: The Performance of History in an Afro‐Venezuelan Community,” American Ethnologist, volume 20, number 3 (1993), pp. 451–73.

Melville J. Herskovits, “African Gods and Catholic Saints in New World Negro Belief,” American Anthropologist, volume 39, number 4 (1937), pp. 635–43.

Melville J. Herskovits, The Myth of the Negro Past (New York: Harper, 1941).

Elizabeth W. Kiddy, Blacks of the Rosary: Memory and History in Minas Gerais, Brazil (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005).

Arthur Ramos, “As Culturas Negras No Novo Mundo,” Bibliotheca de divulgação scientifica, sob a direcção de Arthur Ramos (Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1937).

Erin Kathleen Rowe, Black Saints in Early Modern Global Catholicism (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2019).

Dana Rush, “Eternal Potential: Chromolithographs in Vodunland,” African Arts, volume 32, number 4 (winter 1999), pp. 61–75, 94.

Miguel Valerio, Sovereign Joy (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

Miguel Valerio, “Architects of Their Own Humanity: Race, Devotion, and Artistic Agency in Afro-Brazilian Confraternal Churches in Eighteenth-Century Salvador and Ouro Preto,” Colonial Latin American Review, volume 30, number 2 (2021), pp. 238–71.

Mesi Walton, “Afro-Venezuelan Cultural Survival: Invoking Ancestral Memory,” Middle Atlantic Review of Latin American Studies, volume 4, number 2 (2020).