The Impact of Abstract Expressionism: an overview.

Read Now >Chapter 74

Art into Life: Anti-Modernist Gestures

From the late 19th to the mid-20th century, many artists pushed their practices to be increasingly self-reflexive and autonomous—eventually making paintings that were about the act of painting, or sculptures that were about the medium’s unique qualities such as three-dimensionality. Often these works make little or no reference to art’s embeddedness in social, economic, or historical contexts.

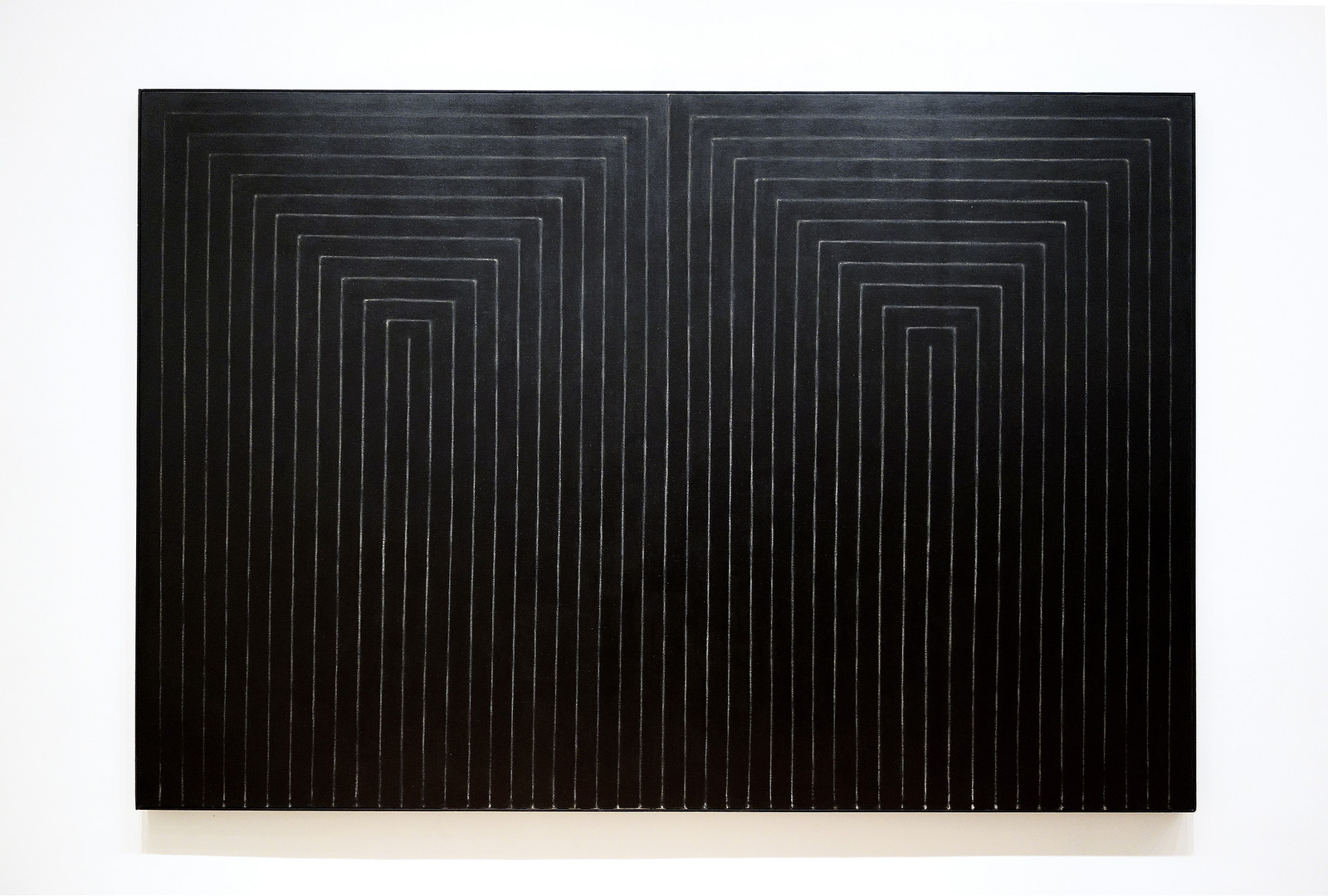

Frank Stella, The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II, 1959, enamel on canvas, 230.5 x 337.2 cm (The Museum of Modern Art)

For instance, Frank Stella allowed the size and shape of his paintings’ frames to determine the linear compositions of each work. This pursuit, which art historians see as one of the hallmarks of late Modernism, turned away from storytelling and naturalistic rendering, such as we see in works by Stella and Kenneth Noland.

In the 1950s and 1960s, however, several artists around the world sought to challenge this idea that art should divorce itself from the messy terrain of “real life.” Describing their work as nearly anything except “painting” or “sculpture,” they instead referred to their works as happenings and encounters, new realisms and arte povera (impoverished art), and as non-objects, specific objects, combines, and tableaux. The critic Allan Kaprow addressed this phenomenon in 1959 when he predicted that the “young artists of today need no longer say ‘I am a painter’ or ‘a poet’ or ‘a dancer.’ They are simply ‘artists.’ All of life will be open to them.” [1] In fact, such sentiments are found in notable quotations by a range of this generation’s leading figures:

In my inner soul art and life are inseparable.Eva Hesse

Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in the gap between the two).Robert Rauschenberg

The picture should not be considered as a world in itself, but the world itself should be seen as a picture.Raymond Haims

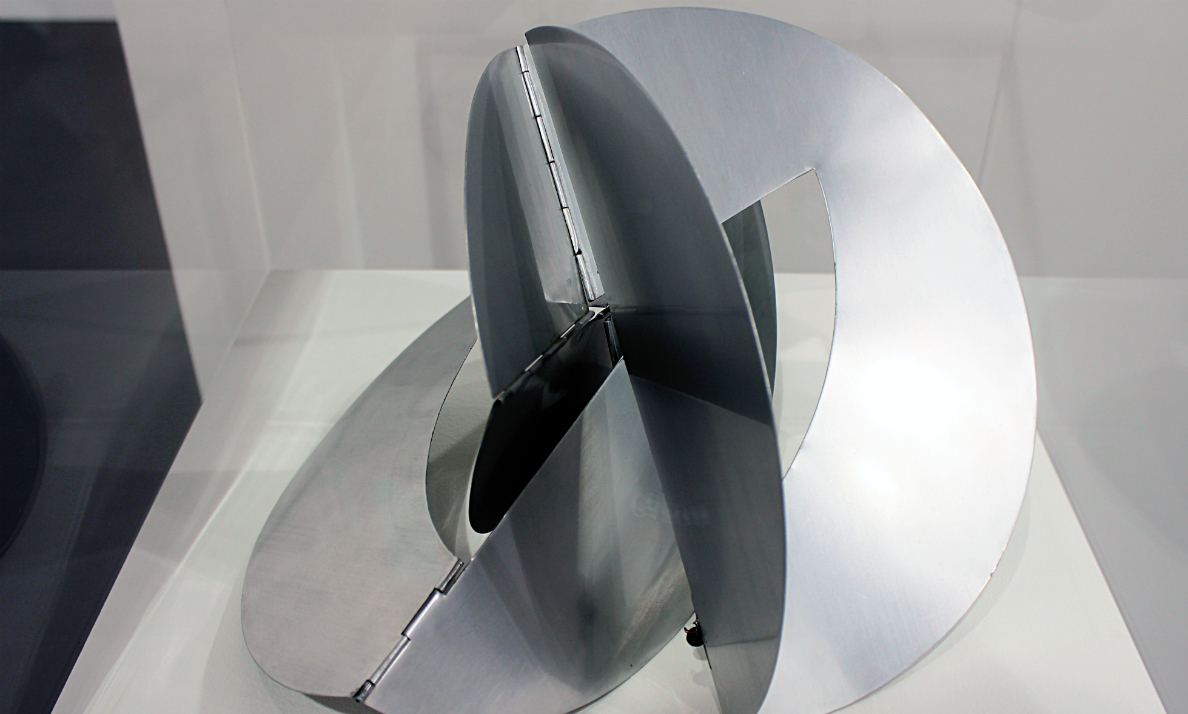

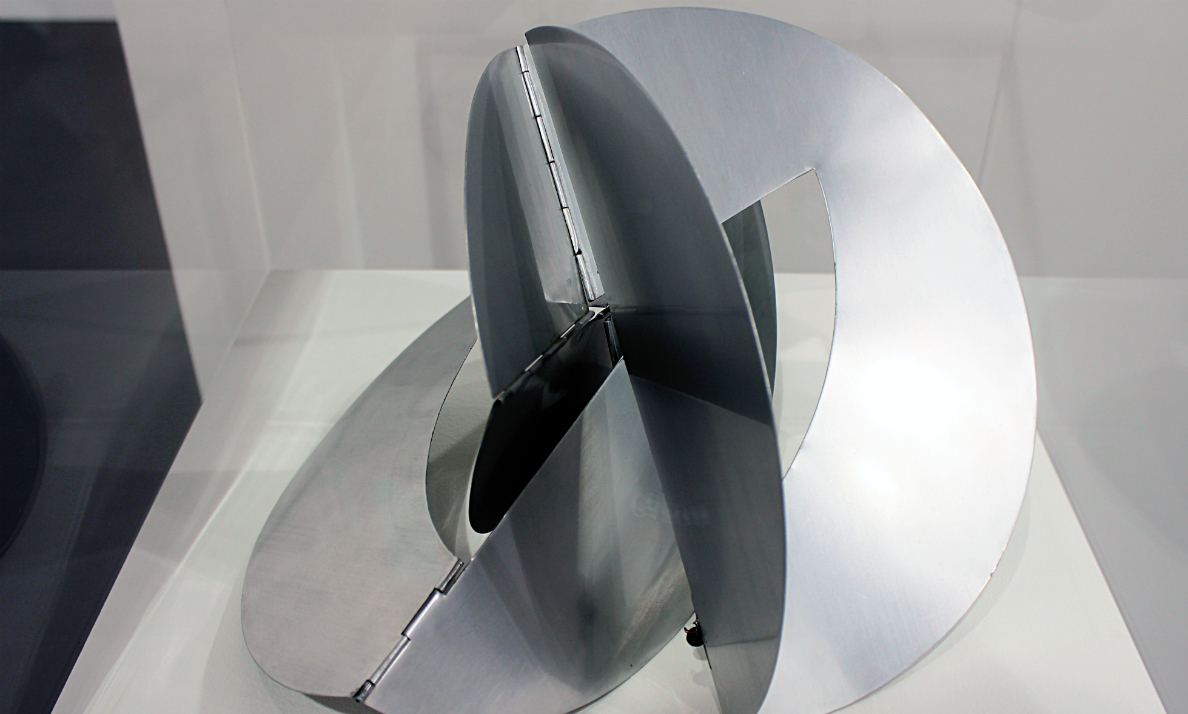

Lygia Clark, Bicho, 1962, aluminum (photo: trevor.patt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This chapter examines a range of anti-Modernist gestures in art of the 1950s and 1960s—when the desire to merge art back with life permeated a wide range of movements, regional politics, and stylistic tendencies. In 1959, for instance, inspired by the work of artist Lygia Clark, Brazilian poet Ferreira Gullar wrote an essay entitled “Theory of the Non-Object”‘ (Teoria do Não-objeto) which proposed that art should constitute a “rediscovery of the world” and a reorientation of what the work of art could be. He advocated for an art he termed the “non-object”: a “presentation instead of a representation”—meaning the work of art was seen as part of the real world, rather than merely depicting it. [2] Gullar’s idea of the non-object is embodied in Clark’s art, which sought to disrupt the boundary between the viewer, the gallery, and the work itself. In the 1960s, for instance, she created interactive sculptures called Bichos, or “critters,” that could be physically manipulated and transformed by participants.

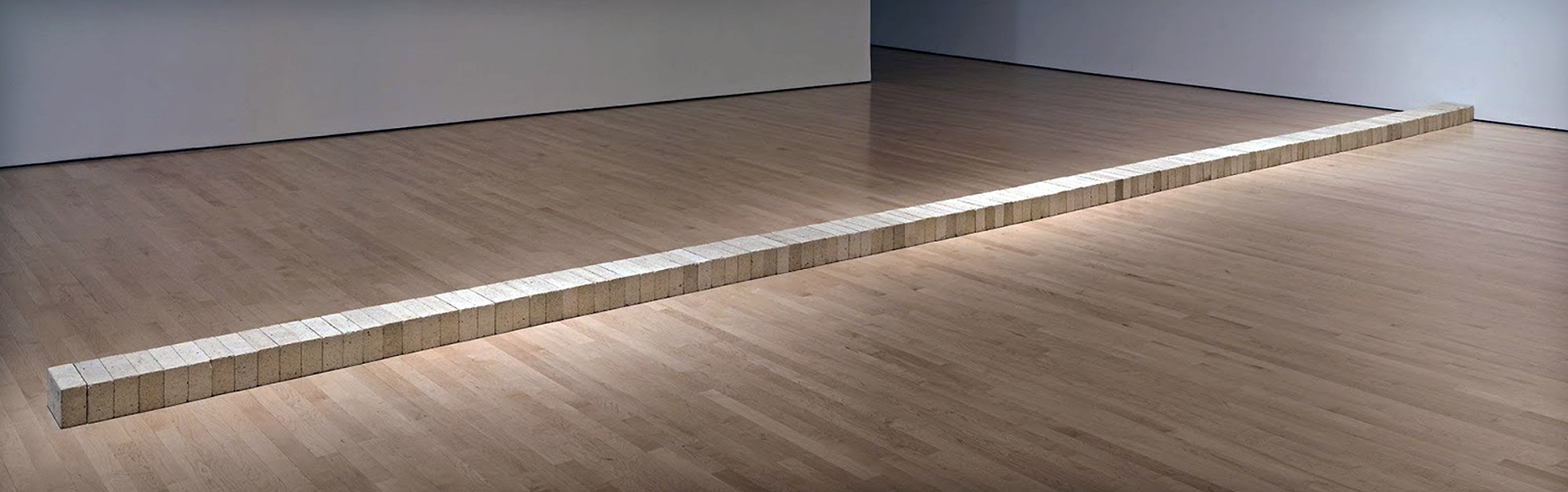

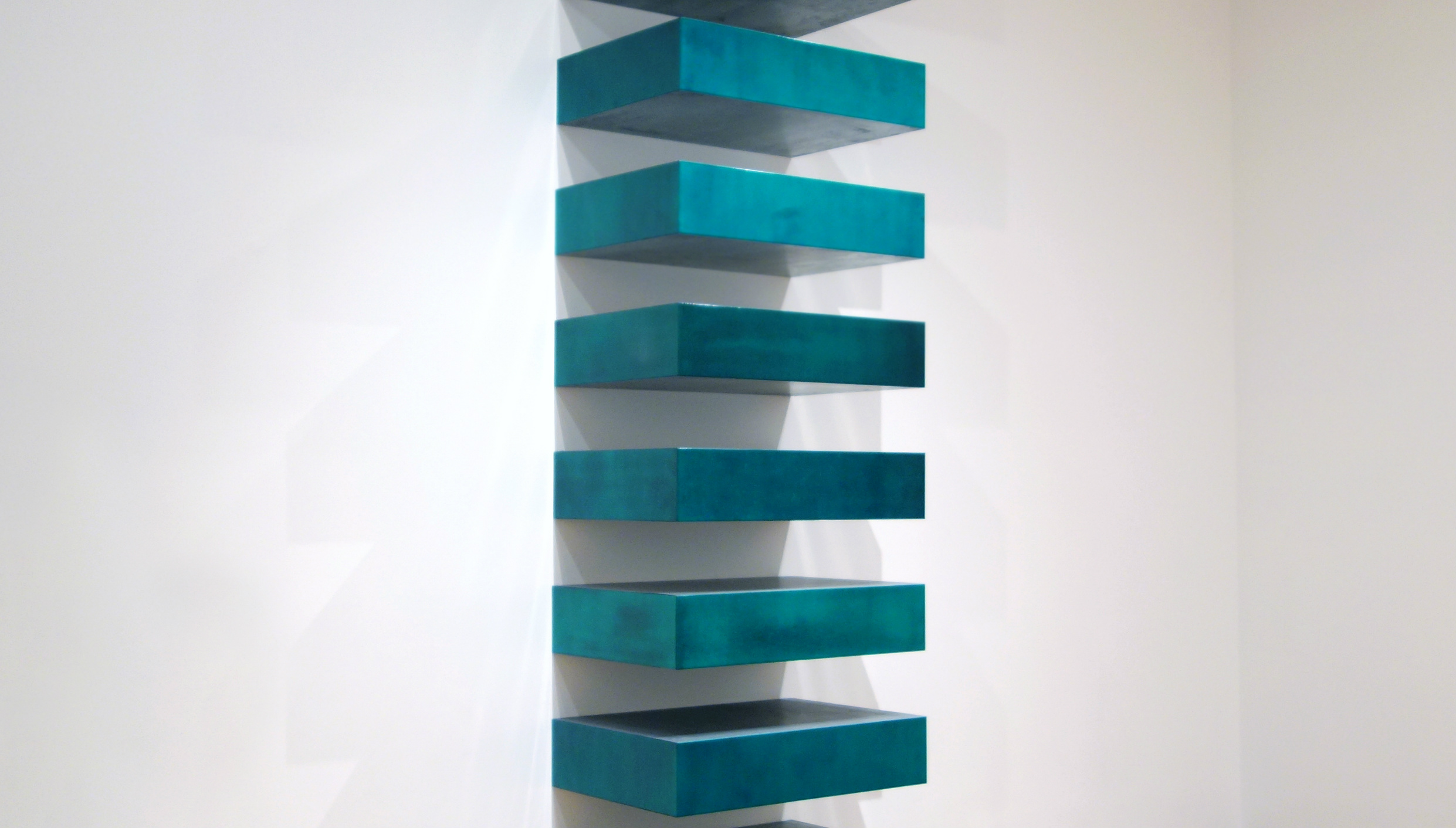

Donald Judd, Untitled (Stack), 1967, lacquer on galvanized iron, twelve units, each 22.8 x 101.6 x 78.7 cm, installed vertically with 9″ (22.8 cm) intervals (MoMA)

Around this time, American artist Donald Judd assessed the work of fellow artists in New York for whom academic categories such as painting and sculpture had become irrelevant. The artist proposed the phrase “Specific Objects” for works such as his own Stacks series (wall-mounted series of six or nine steel and plexiglass units, arranged in a ladder-like formation) which were more concerned with scale and spatial presence (qualities which marked a direct relationship to the viewer) than they were with matters of internal composition.

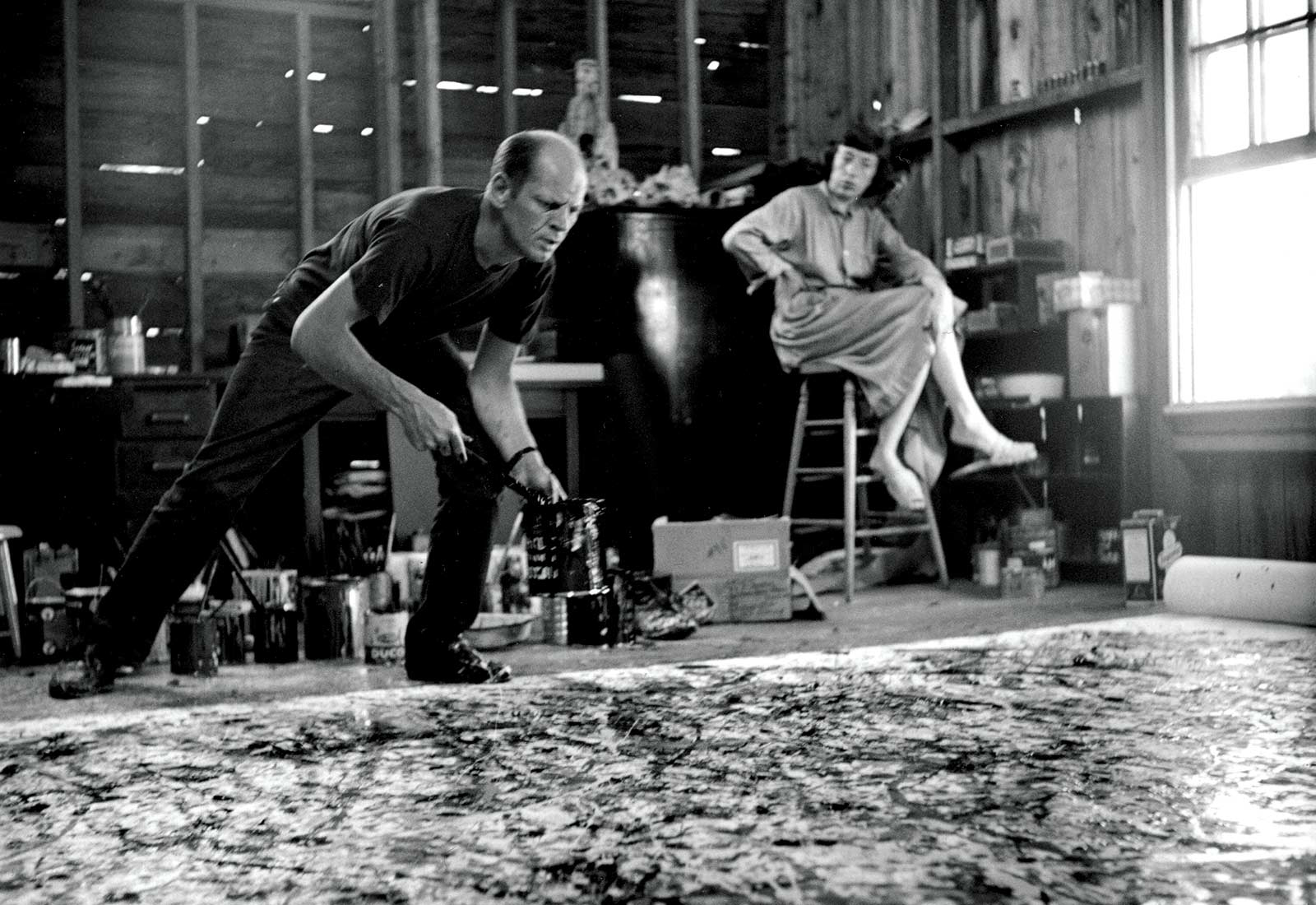

Some critics interpreted this shift as a direct reaction to postwar abstraction, especially in the United States where Abstract Expressionism—a style of abstract painting hailed as deeply psychological, and removed from narrative—had become a popular style. Kaprow wrote on the pivotal role of Jackson Pollock, whose untimely death in 1956 was framed by many as analogous to the end of painting itself.

Hans Namuth, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, 1950, gelatin silver print, sheet: 11 x 10 3/4 inches (28 x 27.3 cm) (© Hans Namuth Estate, Center for Creative Photography)

By placing his canvas horizontally on the floor (rather than using an easel), and treating art-making as a physical act or even a ritual through his dance of drips and splatters, Pollock paved the way for art and life to be rejoined, according to Kaprow. Reflecting on the future of art, Kaprow wrote:

Pollock, as I see him, left us at the point where we must become preoccupied with and even dazzled by the space and objects of our everyday life, either our bodies, clothes, rooms, or, if need be, the vastness of Forty-Second Street. Not satisfied with the suggestion through paint of our other senses, we shall utilize the specific substances of sight, sound, movements, people, odors, touch. [3]

Art at mid-century was created from the most eclectic and unexpected materials: light, motion, sound, found photographs, flea market memorabilia and kitschy souvenirs, newspaper clippings, radio signals, electricity, fabric, stockings, and the artists’ own body or that of a participant. The various movements included in this chapter are remarkably wide-ranging in style, material, and even artistic philosophy or sense of purpose, but each constitutes a gesture towards the re-introduction of “life” into “art” and the intervention of art into life.

Assemblage and Americana

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959, oil, pencil, paper, metal, photograph, fabric, wood, canvas, buttons, mirror, taxidermied eagle, cardboard, pillow, paint tube and other materials, 207.6 x 177.8 x 61 cm (The Museum of Modern Art)

This section explores the genre of assemblage in postwar American art, with a particular focus on the symbolic and subversive ways in which artists utilized found objects loosely identified with Americana (the popular and visual culture of the United States). During the 1950s–60s, motifs such as the Star-Spangled Banner, the American bald eagle, flea-market knick-knacks, roadside souvenirs, Black memorabilia, and portraits of President John F. Kennedy found their way into folksy constructions that intervene in the national zeitgeist as much as they do art historical canon.

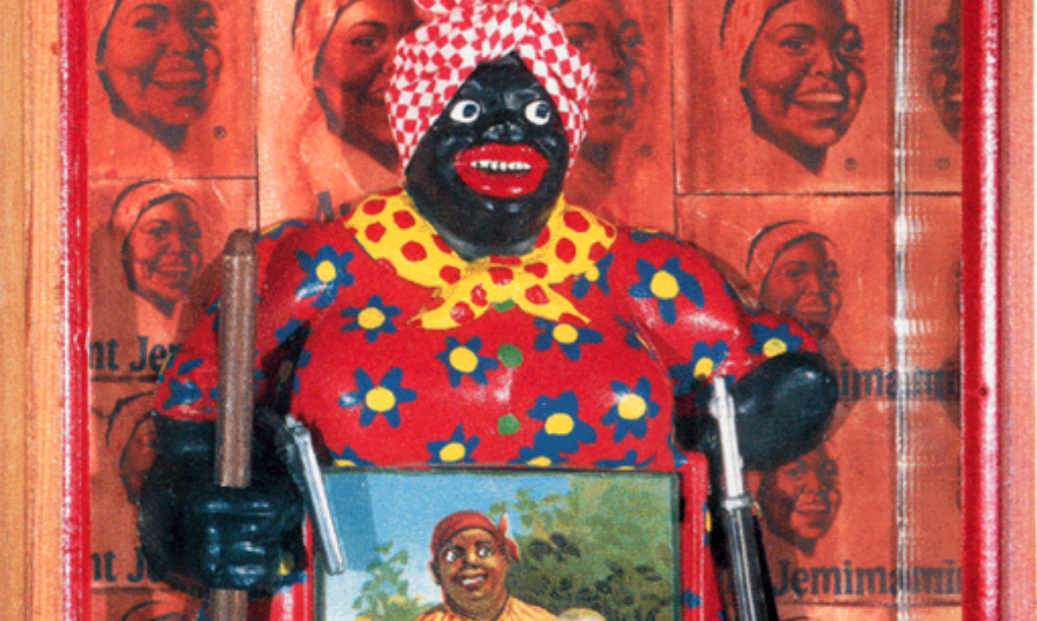

Betye Saar, Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972, assemblage, 11 3/4 x 8 x 2 3/4 inches (Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive)

California-born artist Betye Saar, for instance, interrogated American history and Black identity by using artifacts portraying racist caricatures, in everything from figurines to food packaging. In Saar’s groundbreaking assemblage The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, found objects relaying harmful racial stereotypes are empowered through explicit reference to the era’s liberation politics. As she explains, “I was recycling the imagery, in a way, from negative to positive.” Conversely, in the work of artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, symbols like eagles and flags are used as a conduit through which these artists pose questions surrounding how images communicate with viewers, like a language. While they often claimed their work to be non-political, many art historians have noted the potency that such national symbols carried amidst the Civil Rights movement and the Cold War, suggesting these works might express a subtle critique.

What does it mean for these artists to incorporate “real life” into their work through the use of recycled objects and national symbols? Can such images and objects ever be truly neutral?

Read essays and watch videos about assemblage and Americana

Assemblage: A practice of art production that combines disparate everyday objects and materials to create new meanings and forms, rose to popularity among American artists following World War II.

Read Now >

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon: Rauschenberg combined disparate elements in a random fashion perhaps responding to his urban environment (New York City) and a world of ephemera: the flotsam and jetsam of mass culture in the years after WW II.

Read Now >

Betye Saar, Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Saar boldly attempts to rescue the Mammy character from her demeaning, servile role in this powerful assemblage.

Read Now >

Ed Kienholz and Nancy Reddin Kienholz, Useful Art #5: The Western Motel: This collaboratively created work brings the darkly psychological space of Americana into the gallery.

Read Now >/6 Completed

Nouveau Realisme and Arte Povera

Yves Klein, “Théâtre du vide,” Dimanche: Le Journal d’un seul jour, November 27, 1960. Published on the occasion of the second Festival d’Art d’Avant-garde de Paris; Klein promoted his show by resuming the edition of the Sunday supplement.

On November 27, 1960, the French artist Yves Klein distributed a newspaper bearing the masthead Le Journal d’un Seul Jour—“The Newspaper of a Single Day”—whose cover page featured an unusual and shocking photograph: the artist is pictured mid-air, leaping off the roof of a suburban home, with his body outstretched in a calm and balletic pose. Klein’s serene expression is countered by the viewer’s own terror upon realizing that he will soon succumb to gravity and fall to the cobblestone street. The page contains a bold headline that announces the Théâtre du Vide—“the theatre of life.”

While Klein’s photograph is convincing, it is indeed completely doctored. He publicly circulated the newspaper hoping that readers would feel uncertain of its veracity. Comprising elements of performance, photography, design, and public intervention, Klein’s work compels us to question what is real or fake, art or prank, life or its imitation.

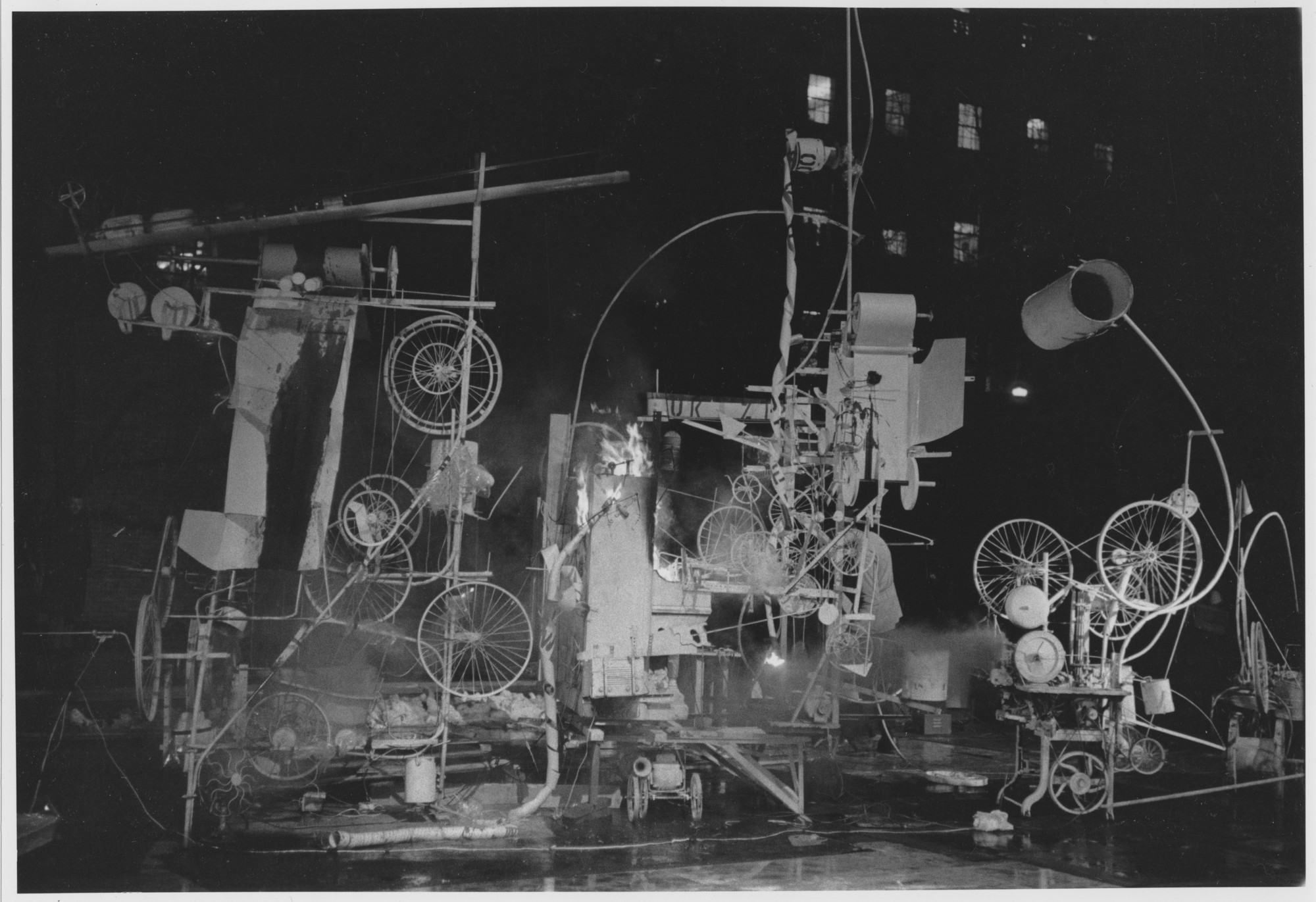

Jean Tinguely, Homage to New York, 1960 (MoMA)

Such concerns are typical of the collective Nouveau Realisme—of which Klein was a member, along with artists like Jean Tinguely, Raymond Haims, and art critic Pierre Restany. This movement sought to blur the distinctions between art and life through a variety of subversive, avant-garde tactics. The name of their movement suggested a distinction from the typical definition of “realism” as a way of representing real-world subjects. Indeed, real life had now become the material and the medium—the art itself.

Mario Merz, Luoghi senza strada, 1994 (photo: (photo: Giovanni Sighele, CC BY 2.0)

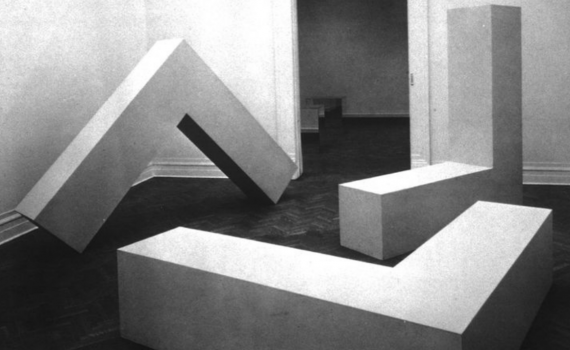

In Italy, the Arte Povera movement proposed a different set of methods for eschewing the traditional rules of art making. Literally translated as “poor (or impoverished) art,” the group used recycled, found, and accessible non-art materials as an anti-capitalist and anti-modernist gesture. Mario Merz’s igloos, for instance, resembled refugee camps or other forms of informal housing—making reference to “real life” through its liminal and nomadic spaces. How does the use of ephemeral or secondhand materials challenge our traditional understandings of fine art?

Read essays and watch videos about Nouveau Realisme and Arte Povera

Jean Tinguely, Homage to New York: Tinguely described the entire construction, laboriously painted in white, as a “a sculpture, a picture, a painting.”

Read Now >

Mario Merz, Giap’s Igloo: Arte Povera artists rarely created politically overt work; instead, they sought to create art that would provoke viewers to question the social and political systems and structures of the world around them.

Read Now >

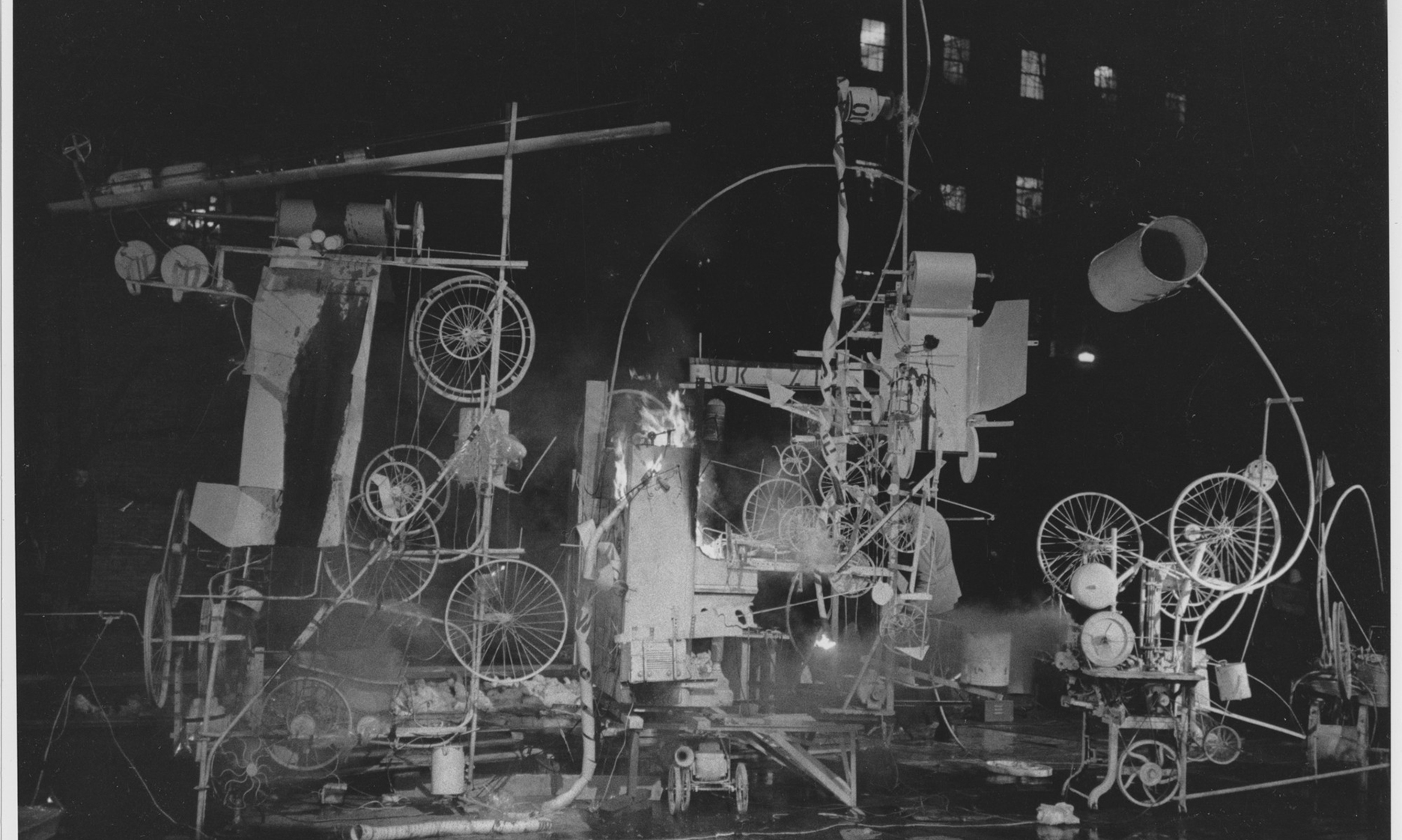

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Newspaper Sphere: A key artist of the arte povera movement, Michelangelo Pistoletto came to London in May to recreate a seminal 1966 performance in which he rolled a ball of newspapers through the streets of Turin.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Ambient Abstraction: Activations of Light and Space

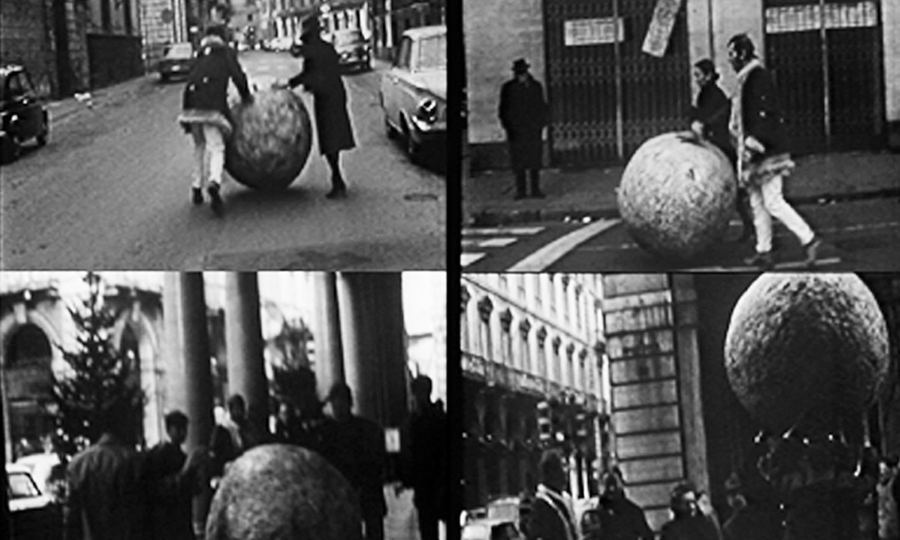

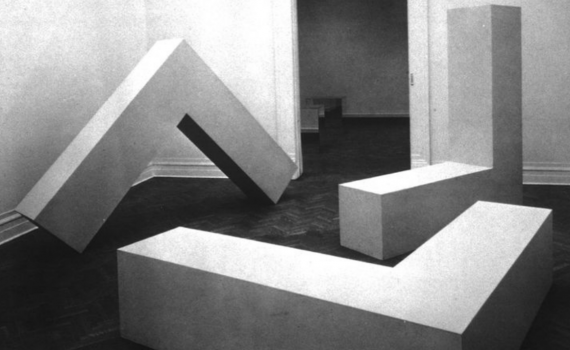

Robert Morris, Untitled (L-Beams), 1965, originally plywood, later versions made in fiberglass and stainless steel, 8 x 8 x 2′

Light, space, scale, and texture became instrumental features of much 1960s art. For instance, the movement known as Minimalism is typically characterized by the use of industrial or mechanically fabricated materials, stark geometric abstraction, repeated units or forms, and a blurring of sculpture and architectural or other structures: qualities that are evident in Robert Morris’s Untitled L Beams or Donald Judd’s series of “Stacks,” each of which occupy the full height or floorspace of interior gallery spaces. Relatedly, artists associated with the Light & Space movement (which was most prominent in California) used neon and natural light to produce an ethereal ambience that surrounded viewers.

Both of these movements were invested in matters of perception and presence. Critic Michael Fried famously referred to Minimalist art as “theatrical”—not as an indication of a kind of a high dramatic narrative that unfolds (which is clearly absent in the movement’s stark and even banal forms), but rather to propose that like live performance, such works seemed to rely on the beholder’s presence before them—a notable contrast to the “autonomy” of Modernist art.

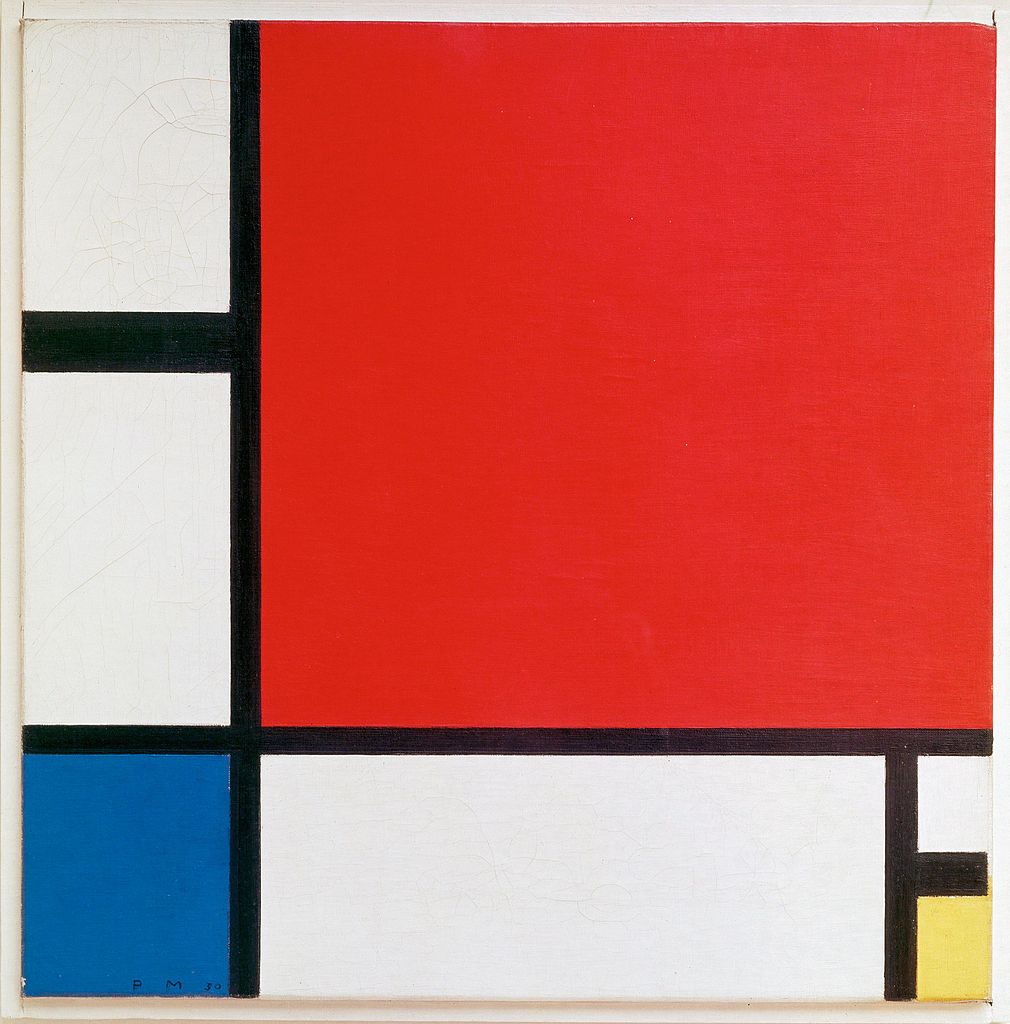

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow, 1930, oil on canvas, 46 x 46 cm (Kunsthaus Zürich; photo: Hannolans, public domain)

In other words, a work of modernist art by, for example, Piet Mondrian was complete in itself. Whereas a work by James Turrell required the retinal experience of the viewer for the work to fully come into being.

James Turrell, Skyscape, The Way of Color, 2009, stone, concrete, stainless steel, and LED lighting 228 x 652 inches © James Turrell (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas)

This section draws examples from these preeminent movements, but also includes similarly minded works by artists not typically included in their rosters, such as Nicolas García Uriburu’s radical pigmenting of an entire waterway in Venice. By composing environments and making their work “ambient,” such artists ask us to focus our attention on space and time, rather than producing timeless art that never shifts in appearance or meaning.

Watch videos and read essays about activations of Light and Space

Robert Morris, (Untitled) L-Beams: By placing two eight-foot fiberglass “L-Beams” in a gallery space (often, he showed three), Morris demonstrated that a division existed between our perception of the object and the actual object.

Read Now >

Donald Judd, Untitled (Stack): Judd’s boxes were made by factory workers, not by the artist—but he provided instructions.

Read Now >

Nicolás García Uriburu, Coloration of the Grand Canal, Venice: By creating a painting with and on a body of water—and which also happened to be the center of Venice’s transportation—the artist relinquished a certain amount of control that painters usually enjoyed in the composition and execution of their works.

Read Now >

James Turrell, Skyspace, The Way of Color: A viewing station for sunrise and sunset, Turrell’s work manipulates light, time, and perception.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Eccentric/Embodied

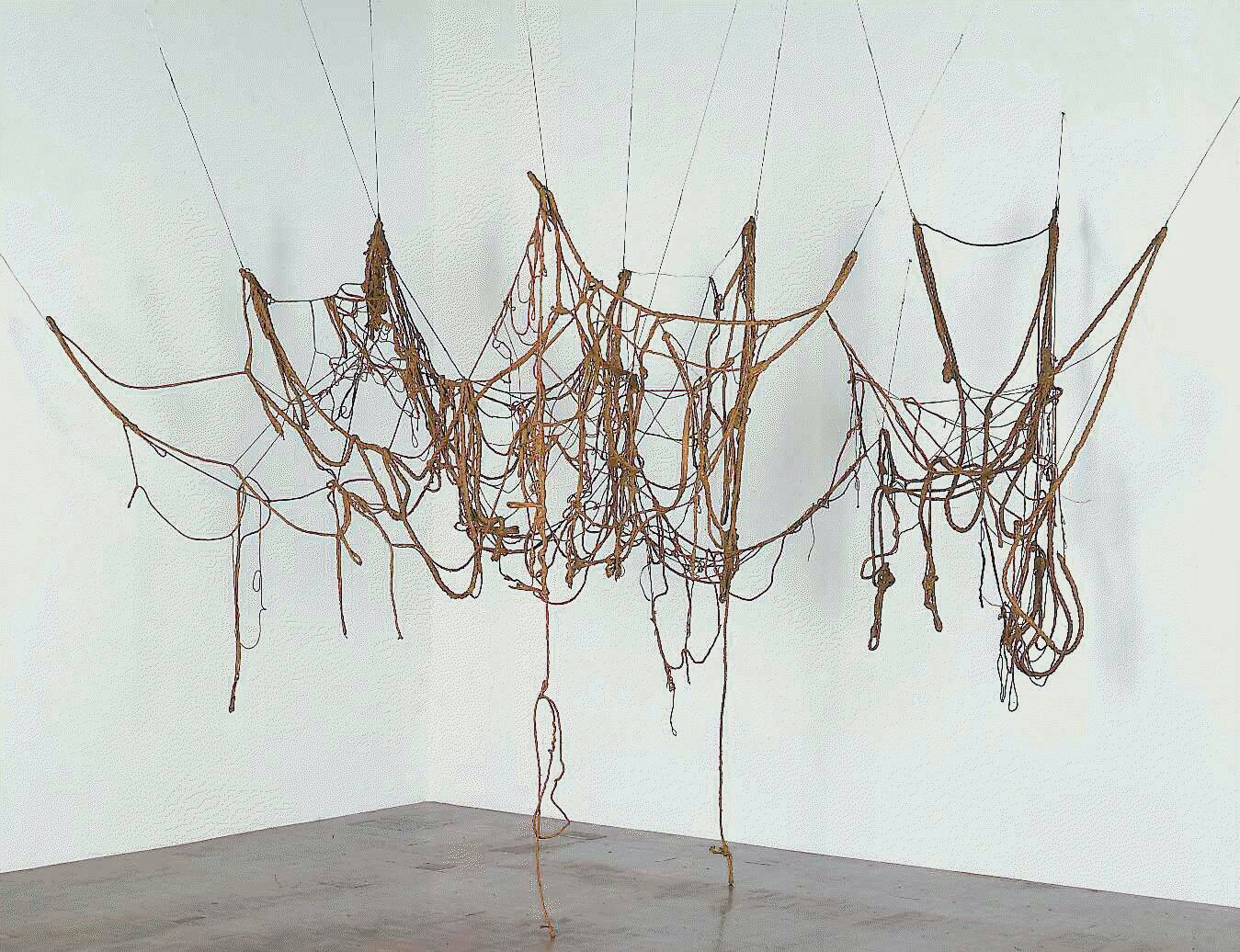

Eva Hesse, Untitled (Rope Piece), 1970, rope, latex, string, wire, variable dimensions (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York)

Among the defining exhibitions of the late 1960s was Eccentric Abstraction, curated by art critic Lucy Lippard in 1966. This group show spotlighted practices now loosely referred to as postminimalism and anti-form, where the sleek geometric abstraction of that decade’s earlier years was swapped for art that referenced the body or could transform through processes like pouring, seeping, spilling, or swaying. Among the included artists was Eva Hesse, a German-Jewish immigrant whose abstract sculptures—often made from flexible materials like latex or string—were suspended from the ceiling or protruded from the wall into the viewer’s space. Likewise, artist Yayoi Kusama created immersive installations of repeated forms, typically containing sexual and bodily reference and made from plushy or reflective materials. For Kusama, these spatial interventions conveyed experiences of anxiety and psychological terror.

Hélio Oiticica, Parangolé P4 Cape 1, 1964, acrylic on canvas, fabric, nylon, rope and plastic, 93 x 160 x 10 cm (MAM Rio Collection)

Many artists in the 1960s combined sculpture with performance to infuse their work with a similar sense of vitality. Often, such objects were intended to be manipulated, activated, or “danced”—such as Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica’s Parangolés (colorful capes that could be worn by participants during street performances and in the galleries), and African American artist Senga Nengudi’s limb-like sculptures created from nylon stockings, which she filled with sand and stretched across corners, walls, and floors of the gallery.

Senga Nengudi, Performance Piece (detail), 1977, activated by Maren Hassinger (Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau München, Sammlung KiCo) © Senga Nengudi

As the artist explained:

I am working with nylon mesh because it relates to the elasticity of the human body . . . from tender, tight beginnings to sagging . . . the body can only stand so much push and pull until it gives way, never to resume its original shape.

Both of these artists, in their own way, saw participation and interaction as methods of resisting the conditions experienced under dictatorial or otherwise oppressive political regimes.

Watch videos and read essays about the eccentric and embodied

Lygia Clark, Bicho: A viewer can fold, turn, close, and open Bicho, exploring its multifaceted nature.

Read Now >

Senga Nengudi: An artist best known for her abstract sculptures that combine found objects and choreographed performance.

Read Now >

Yayoi Kusama, Narcissus Garden: These metal balls draw attention to the economic system embedded in art, and the vanity of its viewers.

Read Now >

/6 Completed

The works in this chapter defy easy categorization—they are feminist, neoconcrete, post-minimalist and performance-based. Yet each is marked by a sense of vivid materiality, reference to the body, and the capacity for transformation and change. And each seeks to narrow the divide between the art, and the world it exists within.

Notes:

[1] Allan Kaprow, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” Art News (October 1958): p. 57.

[2] Ferreira Gullar, “Theory of the Non-object” Jornal de Brazil, December 1959. As quoted in Monica Amor, “From Work to Frame, In Between, and Beyond: Lygia Clark and Hélio Oiticica, 1959-1964”

[3] Allan Kaprow, “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” Art News (October 1958): p. 56.

Key questions to guide your reading

What are the various methods that artists used to try and merge “art” with “life”?

What led artists to make use of found images, recycled objects, and discarded materials in the 1960s? How do these materials transform when they are codified as “art”?

How might the practices explored in this chapter work to challenge the definition of “sculpture”?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat are the various methods that artists used to try and merge “art” with “life”?

What led artists to make use of found images, recycled objects, and discarded materials in the 1960s? How do these materials transform when they are codified as “art”?

How might the practices explored in this chapter work to challenge the definition of “sculpture”?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

anti-form

Arte Povera

Americana

assemblage

combine

Light & Space

Minimalism

Neo-Concrete Art

Neo-Dada

Nouveau Realisme

participation

performance

Post-Minimalism

process art

tableau