Jean Tinguely, Homage to New York, 1960 (MoMA)

A self-destructing spectacle

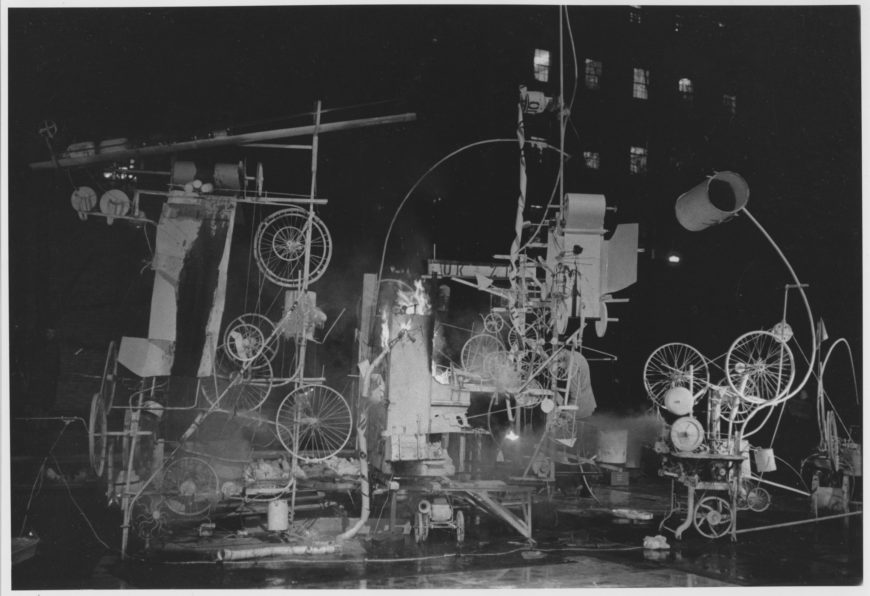

In the spring of 1960, Homage to New York counted as one of the most exciting artistic events of the season. To create his spectacularly exploding machine, Swiss artist Jean Tinguely forged together a 23-foot-long by 27-foot-high assemblage of bicycle wheels, motors, metal drums, an old address labeling machine, a child’s go-cart, a piano, and an enameled bathtub—all disparate emblems of industrial modernism. The resulting assemblage was built to slowly self-destruct before an invited audience, and it did just that in the garden of The Museum of Modern art on a Thursday evening in March. As if to erase any doubt as to its artistic merits, Tinguely described the entire construction, laboriously painted in white, as a “a sculpture, a picture, a painting.” Delay timers were used to control the 15 motors that powered its various parts at intervals, as the artist began to dismantle other parts to assist in its self-destruction. After 30 minutes the entire thing buckled; its component parts lay smoking on the ground in ruins. As museum patrons sorted through the ruins for artistic souvenirs, the Fire Department arrived (unplanned) to put a stop to the whole affair.

It must surely have seemed that a new era was dawning— Pop Art was in its infancy, and the heroic period of the Post-war abstract painters and sculptors (such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning) was entering its twilight. The American art critic Clement Greenberg had written an essay in 1959 called “New York Only Yesterday,” its title already tinged with a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era of the large gestural abstractions Greenberg had championed early on. Newer movements like happenings and performance art would soon become the talk of town.

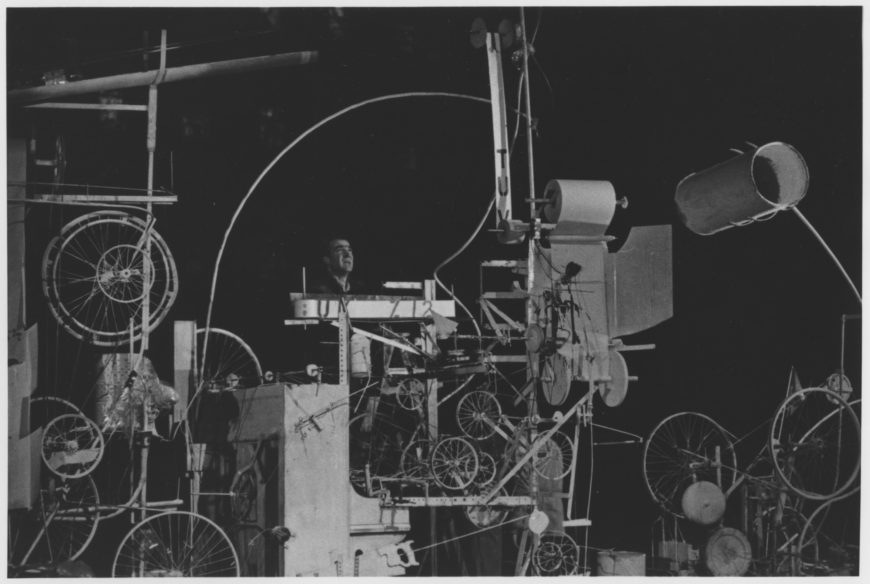

Jean Tinguely installing Homage to New York, 1960 (MoMA)

A New Realism

Tinguely (himself only 30) had attached himself to the daring innovations of young artists like Robert Rauschenberg and the engineer Billy Kluver who collaborated with Tinguely on parts of Homage to New York. In October of 1960, Tinguely would participate in the creation of new movement: he signed The Nouveau Réalisme Manifesto along with a number of mostly French artists in the Parisian apartment of Yves Klein, all of whom advocated for a new kind of art, a “new realism” as the title of the manifesto translates. New realism sought to dissolve the distinction between art and the everyday world and often sought to create work out of the detritus of everyday life: fragments of movie posters, garbage, and for Tinguely, an enameled bathtub.

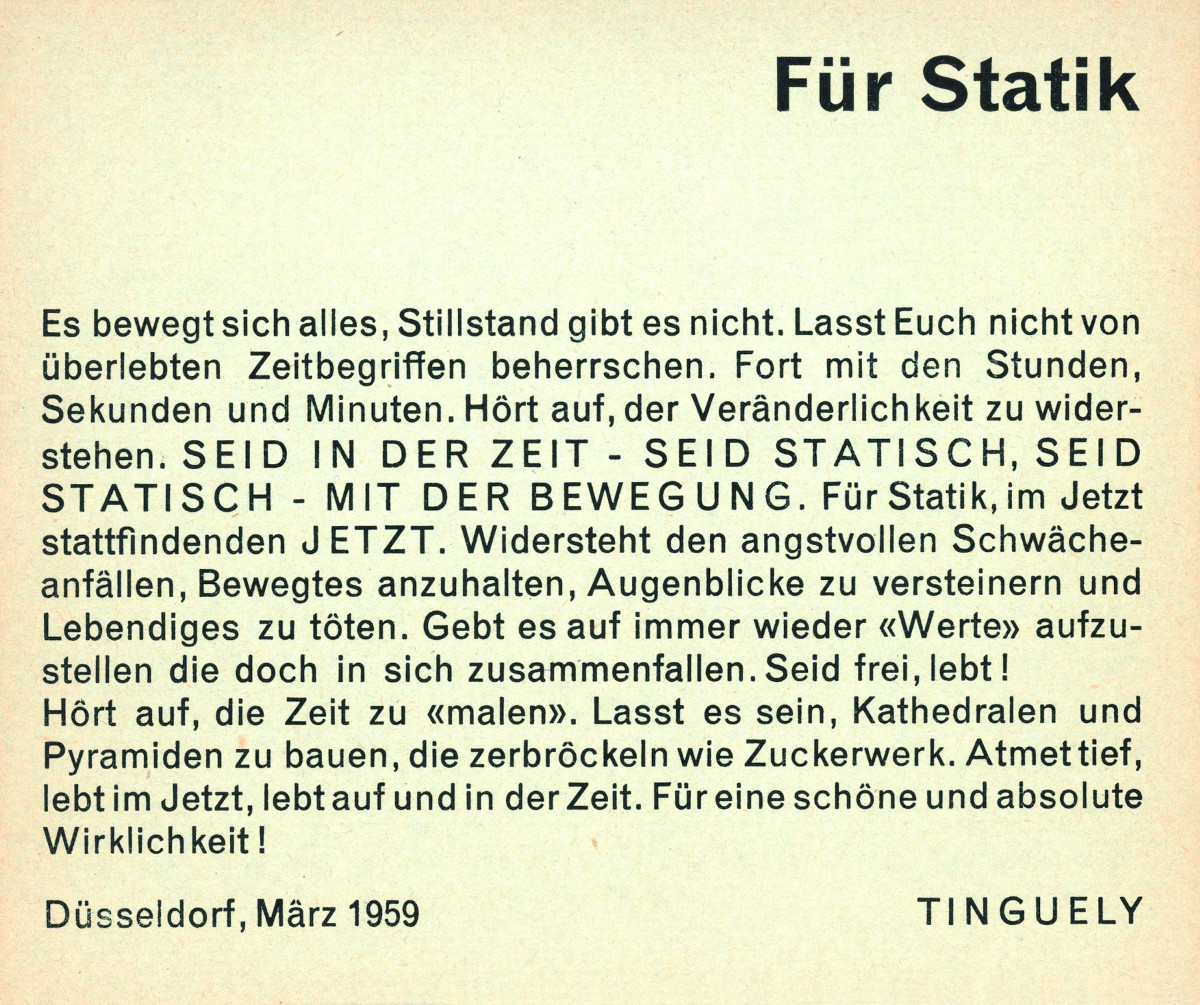

Another of Tinguely’s contributions included an artistic action, in 1959, in which he dropped 150,000 copies of his manifesto Für Statik (“For Statics”) on the German city of Dusseldorf and its suburbs. This action made clear reference to the dropping of propaganda leaflets during the Second World War which had only ended fourteen year earlier.[1]

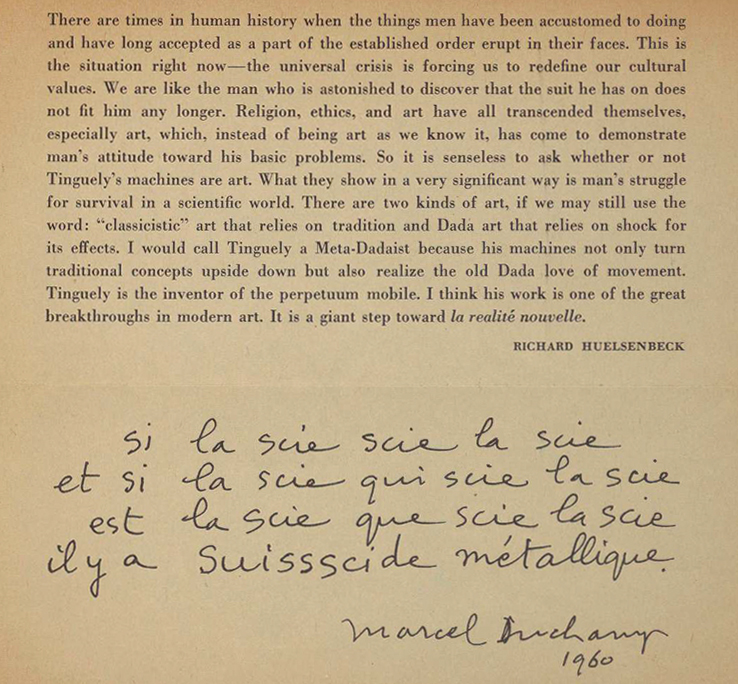

The provocative strategies of these artists recalled the antics of the early twentieth-century Dada movement, a fact that did not go unnoticed by some of its surviving members. Both Richard Huelsenbeck and Marcel Duchamp enthusiastically endorsed Tinguely’s new take on an old anti-art tactic of destruction: Huelsenbeck wrote a brief for MoMA’s press release and Duchamp, with his characteristic love of puns, wrote a word play on Tinguely’s Swiss origins: “Il y a un swissscide metallique” (roughly, “it is a metallic Swiss suicide”).

Statements from Richard Huelsenbeck and Marcel Duchamp, Museum of Modern Art, “Homage to New York: a self-constructing and self-destroying work of art conceived and built by Jean Tinguely, the Museum of Modern Art Sculpture Garden, March 17, 1960, 6:30-7:00 P.M,” press release, 1960 (MoMA)

Art and industrialization

Yet for all its seeming newness, Tinguely’s Homage to New York spoke to a sentiment of the modern period that had haunted its culture for a long time. Industrialization has featured as an anxious part of modern art for a least as long as the 250 years or more since the Industrial Revolution. Its implications were evident with the advent of photography: the mechanical replication of landscapes, portraits, and urban scenes threatened to nudge the making of art, with its association of the unique characteristics of the hand, from its exalted position within modern life. Artistic life was soon defined by its turning away from the crasser aspects of modernization, reveling instead, as in the example of the Romantic landscape painting movement of the early nineteenth century, in the sublime features of nature, ignoring, at least for the moment, the devastation of the wilderness wrought by the forces of modernization.

Jean Tinguely, Sketch for Homage to New York, 1960, felt-tip pen and ink on board, 22 1/8 x 28 inches (MoMA)

In the second half of the nineteenth century, we see the identity of the artist as flâneur—a figure based in literature (who first appeared in a story by Edgar Allan Poe) who would reject the conventions of society with its rhythms of life increasingly corresponding to the punctuality and routine of factory life. Flâneurs, detached from purpose and wandering the boulevards of late nineteenth-century Paris, became popular in literature and art. They were the observers, walking turtles on leashes, the pace of which defied the speeded-up sense of time that modern life now demanded. The flâneur’s disdainful observation of the world of contemporary urban society became a template for the modern artist’s withdrawal from society. When Paul Gauguin famously proclaimed that “I am a savage” he was announcing his rejection of industrial modernity.

But Tinguely is on the opposite end of this spectrum of anxiety around industrialization that runs throughout modern art. On the cusp of the 1960s, his art embraced the machine, if only as a symbol of the destructive nature of the modern world, or at least as an example of his, and our, disillusionment with Modernism’s promise of utopia, a promise that seems only to recede.

Jean Tinguely – Homage to New York (1960) from Stephen Cornford on Vimeo.