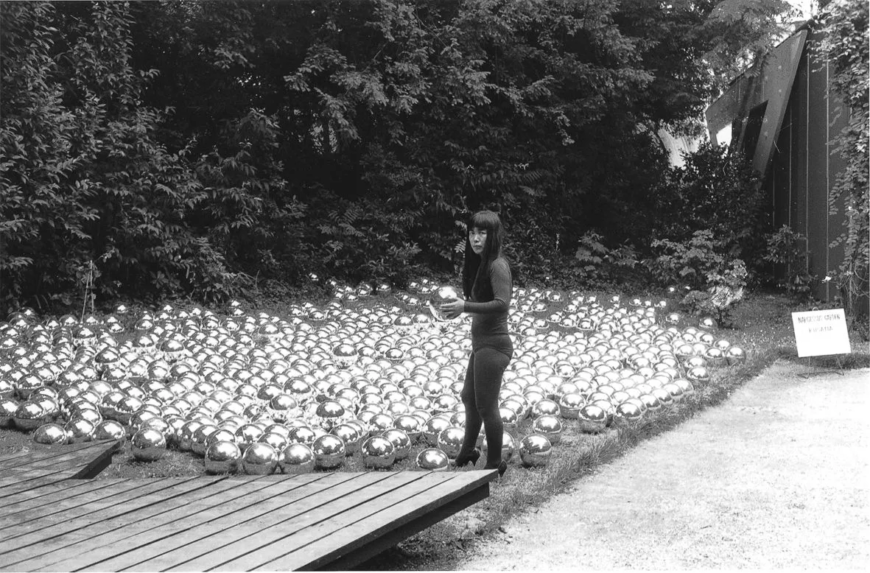

Yayoi Kusama lying in Narcissus Garden, 1966, installed in Venice Biennale, Italy, 1966 (photo: Yayoi Kusama Studio) © YAYOI KUSAMA. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Narcissism

Today there are few female artists who are more visible to a wide range of international audiences than Yayoi Kusama, who was born in 1929 in Japan. Kusama is a self-taught artist who now chooses to live in a private Tokyo mental health facility, while prolifically producing art in various media in her studio nearby. Her highly constructed persona and self-proclaimed life-long history of insanity have been the subject of scrutiny and critiques for decades. Art historian Jody Cutler places Kusama’s oeuvre “in dialogue with the psychological state known as narcissism,” as “narcissism is both the subject and the cause of Kusama’s art, or in other words, a conscious artistic element related to content.” [1] It is within this context that we examine Kusama and her infamous Narcissus Garden (narcissism is, in part, the egotistic admiration of one’s self).

Mirrors

Kusama arrived in New York City from Japan in 1958 and immediately approached dealers and artists alike to promote her work. Within the first few years she began to exhibit and associate herself with seminal artists and critics, such as Donald Judd, Joseph Cornell, Yves Klein, and Lucio Fontana who later was instrumental in her realizing Narcissus Garden.

Installation view, Infinity Mirror Room—Phalli’s Field (or Floor Show), (no longer extant) Castellane Gallery, New York, 1965 (photo: © Eiko Hosoe)

In 1965, she mounted her first mirror installation Infinity Mirror Room-Phalli’s Field at Castellane Gallery in New York. A mirrored room without a ceiling was filled with colorfully dotted, phallus-like stuffed objects on the floor. The repeated reflections in the mirrors conveyed the illusion of a continuous sea of multiplied phalli expanding to its infinity. This playful and erotic exhibition immediately attracted the media’s attention.

Yayoi Kusama, Narcissus Garden, 1966, installed in Venice Biennale, Italy, 1966 (photo: Yayoi Kusama Studio) © YAYOI KUSAMA. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Narcissus Garden, 1966

The pinnacle of her succès de scandale culminated in the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966. Although Kusama was not officially invited to exhibit, according to her autobiography, she received the moral and financial support from Lucio Fontana and permission from the chairman of the Biennale Committee to stage 1,500 mass-produced plastic silver globes on the lawn outside the Italian Pavilion. The tightly arranged 1,500 shimmering balls constructed an infinite reflective field in which the images of the artist, the visitors, the architecture, and the landscape were repeated, distorted, and projected by the convex mirror surfaces that produced virtual images appearing closer and smaller than reality. The size of each sphere was similar to that of a fortune-teller’s crystal ball. When gazing into it, the viewer only saw his/her own reflection staring back, forcing a confrontation with one’s own vanity and ego.

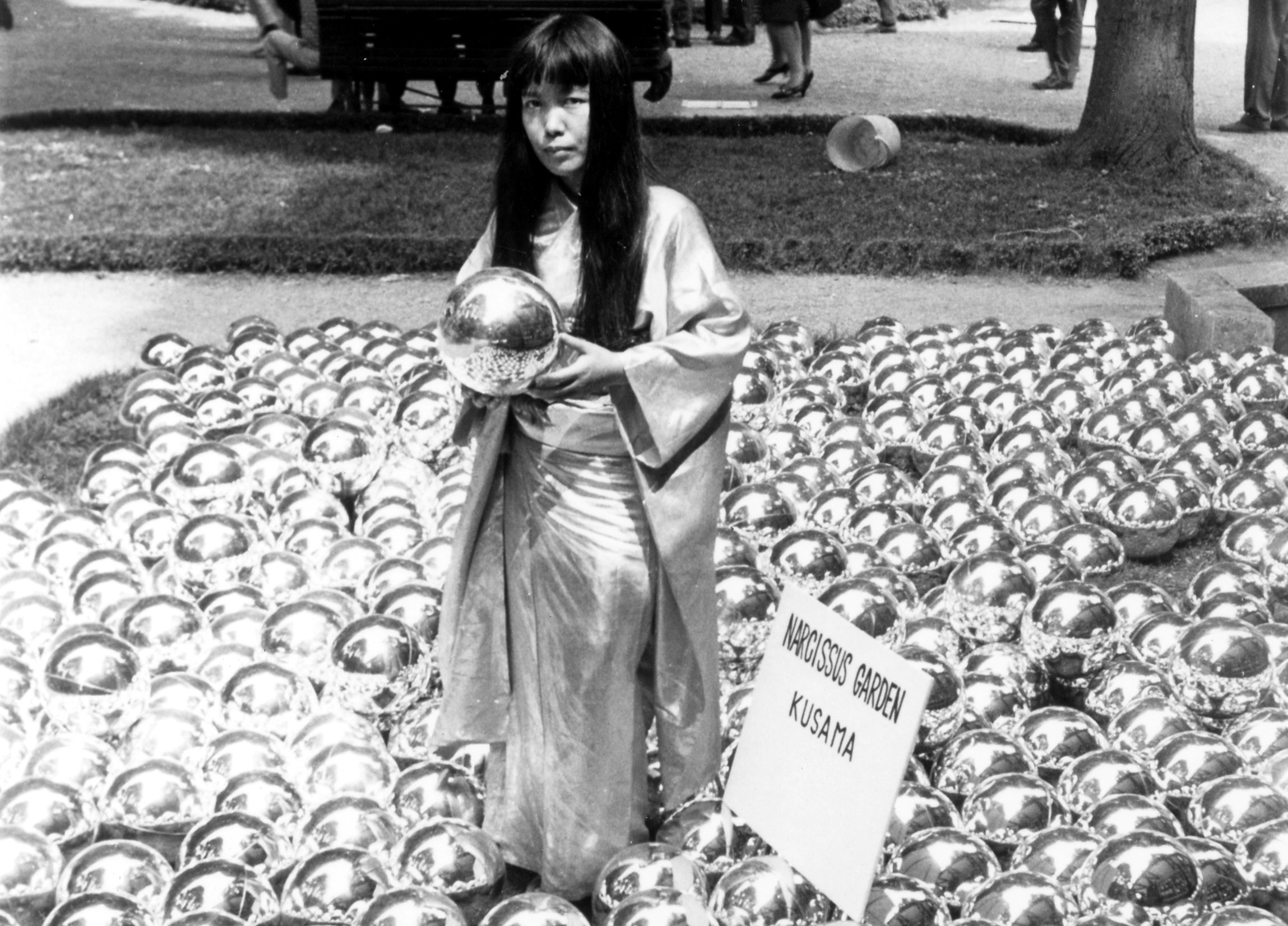

Yayoi Kusama with Narcissus Garden, 1966, installed in Venice Biennale, Italy, 1966 © YAYOI KUSAMA. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

During the opening week, Kusama placed two signs at the installation: “NARCISSUS GARDEN, KUSAMA” and “YOUR NARCISSIUM [sic] FOR SALE” on the lawn. Acting like a street peddler, she was selling the mirror balls to passers-by for two dollars each, while distributing flyers with Herbert Read’s complimentary remarks about her work on them. She consciously drew attention to the “otherness” of her exotic heritage by wearing a gold kimono with a silver sash. The monetary exchange between Kusama and her customers underscored the economic system embedded in art production, exhibition and circulation. The Biennale officials eventually stepped in and put an end to her “peddling.” But the installation remained. [2] Her interactive performance and eye-catching installation garnered international press coverage. This original installation of Narcissus Garden from 1966 has been frequently interpreted by many as both Kusama’s self-promotion and her protest of the commercialization of art. [3]

Yayoi Kusama with Narcissus Garden, 1966, installed in Venice Biennale, Italy, 1966 (photo: Yayoi Kusama Studio) © YAYOI KUSAMA. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore/Shanghai; Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

The life of Narcissus Garden after 1966

Yayoi Kusama, mirror balls, Narcissus Garden, Inhotim (Brazil) installation, original installation and performance 1966 (photo: emc, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Since then, Kusama’s oeuvre has become integrated into the canon of art history, and popular with art institutions around the world. In 1993, Kusama was officially invited to represent Japan at the 45th Venice Biennale.

Her Narcissus Garden continues to live on. It has been commissioned and re-installed at various settings, including the Brazilian business tycoon Bernardo de Mello Paz’s Instituto Inhotim (left), Central Park in New York City, as well as retail booths at art fairs.

The re-creation of Narcissus Garden has erased the notion of political cynicism and social critique; instead, those shiny balls, now made of stainless steel and carrying hefty price tags, have become a trophy of prestige and self-importance. Originally intended as the media for an interactive performance between the artist and the viewer, the objects are now regarded as valuable commodities for display.

Yayoi Kusama, mirror balls, Narcissus Garden, Inhotim (Brazil) installation, original installation and performance 1966 (photo: emc, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The profound narcissistic undertone however has been ironically amplified not only by the artist’s pervasive ostentation, but also by the viewership in the age of Internet. Seduced by his/her own reflective images on the convex surfaces, viewers snap photographs with a smart phone and instantly upload them to social media for the rest of the world to see. The urge to capture and disseminate the moment one’s own image coalesces onto a privileged object in a privileged institution seems to motivate the obsession with the self. To further accentuate the effect of gazing at one’s multiple selves, many installations now take place on the water where the original Narcissus from the Greek mythology fell in love with his own reflection and eventually drowned.

Notes:

[1] Jody Cutler, “Narcissus, Narcosis, Neurosis: The Visions of Yayoi Kusama,” Contemporary Art and Classical Myth, edited by Isabelle Loring Wallace, Jennie Hirsh (London: Ashgate Publishing ltd, 2011), p. 89.

[2] There are a few discrepancies in the anecdote of this event between Kusama’s autobiography and art historians and critics. For example, 1) Kusama claims that the installation was not exactly a guerrilla act, because she received permission from the Biennale official, though she did not have an official invitation as a Biennale participant; 2) according to Kusama, the installation itself was NOT removed after she was asked to stop selling the balls; and 3) in her autobiography, the balls were made of plastic in 1966 not stainless steel.

[3] It is worth noting that the following Venice Biennale, in 1968, was marked by social and economic turmoil around the globe, and was struck by the student movement in Italy and a boycott by international artists. The Biennale was labeled as fascist, capitalist, and commercial. In contrast to Kusama’s action, many artists who were officially invited to participate decided to close exhibition halls, withdraw their works, and join street demonstrations resulting in the closure of the Biennale sales office and the end of Biennale prizes until 1986.

Additional resources

Kusama and Experimentation (Tate blog)

Kusama and Self-obliteration (Tate blog)

Yayoi Kusama—Obsessed with Polka Dots, video by Tate

TateShots: Kusama’s Obliteration Room

Yayoi Kusama, Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama, translated by Ralph McCarthy (London: Tate Enterprises Ltd., 2013) (see the section, “On an endless Highway”).