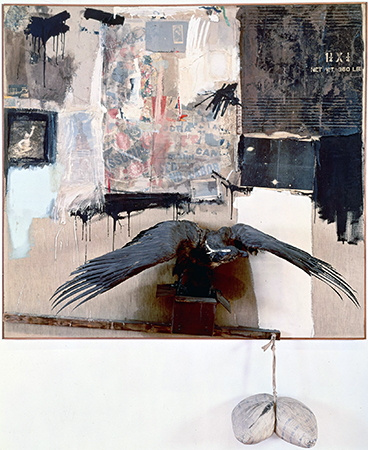

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon, 1959, oil, pencil, paper, metal, photograph, fabric, wood, canvas, buttons, mirror, taxidermied eagle, cardboard, pillow, paint tube and other materials, 207.6 x 177.8 x 61 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © 2014 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Is Canyon a painting or sculpture? Its upper half is a mass of materials that include bits of a shirt, printed paper, a squashed tube of paint, and photographs all seemingly held in place by broad slashes of house paint, while its lower half consists of a stuffed bald eagle with outstretched wings about to lift off from an opened box. The box seems to balance precariously upon a beam that tilts downward to the right; its end point meets the frame. As if that were not enough, that beams suspends a pillow dangling below the frame and squeezed in half by the cloth string that holds it.

Combines

Canyon belongs to a group of artworks called “Combines,” a term unique to this artist who attached extraneous materials and objects to canvases in the years between 1954 and 1965. What makes Rauschenberg so significant for this period—the postwar years—is how he challenged conventional ways of thinking about advanced modern art; especially the art of “The New York School,” a group of émigré Europeans and like-minded American artists (including Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and their followers), who were praised for their heroic abstraction. Rauschenberg’ s art violated the rules.

While the the word “Combine” has no known origin in an art context, it describes Rauschenberg’s hybrid approach to art making which dismantled the rigid medium-specific categories so dear to modernist culture. In the American art critic Clement Greenberg’s influential theory, so-called true painting was to explore only the properties inherent to painting: gesture, flatness and color. Sculpture was to adhere strictly to the delineation of volume and mass. Both would necessarily be abstract since the truth-to-materials maxim of post-war modernism meant that any kind of illusionism (bronze pretending to be flesh or paint attempting to resemble the thing it represented) was anathema. “Subject matter,” in Greenberg’s infamous declaration, “becomes something to be avoided like a plague.”[1] With Canyon, like any number of Combines the artist created during this period, all of this was put into question. Not only did the artist subvert the distinction between painting and sculpture, he reintroduced subject matter and narrative back into art. The art historian Leo Steinberg declared that Rauschenberg’s Combines “let the world back in again.”[2]

Rembrandt, Abduction of Ganymede, 1635, oil on canvas, 177 x 129 cm (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden)

Reading Canyon

Canyon is not an entirely abstract work of art. But what exactly is the subject matter? On the face of it, it seems to be a wryly comic re-telling of the Greek myth in which the god Zeus, disguised as an eagle, abducts a youth named Ganymede. The subject had of course appeared in art before. There are, for example, Greek vases, Roman reliefs and European oil paintings dedicated to this story. Rembrandt’s Abduction of Ganymede, 1636—to which Rauschenberg’s version might readily be compared—paints the story in the lurid richness of oil with a dramatically diagonal arrangement of the figures. Or could it even be a reference to the “scales of Justice” so often found in the art and architecture of Europe and America? It would be a mistake to read Canyon narrowly using only conventional iconography. Although some art historians have sought to “read” Canyon as one would a traditional representional artwork, Rauschenberg’s work seems to resist fixed decoding in favor of a more open-ended play of meaning.

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon (detail), 1959, oil, pencil, paper, metal, photograph, fabric, wood, canvas, buttons, mirror, taxidermied eagle, cardboard, pillow, paint tube and other materials, 207.6 x 177.8 x 61 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © 2014 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Rauschenberg combined disparate elements in a random fashion perhaps responding to his urban environment (New York City) and a world of ephemera: the flotsam and jetsam of mass culture in the years after the Second World War. Look, for example, at the top right: here is a slab of cardboard with commercial lettering, probably the discarded packaging for a shipment of goods found on the street in his lower Manhattan neighborhood. In this sense he anticipated the later work of Pop artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist who would, a few years later, make such commercial imagery the focus of their art.

Cultural debris

Rauschenberg did know other artists who took a similar approach and challenged the narrow parameters of the formalists wing of the New York School and its rejection of popular culture and illusionism. His immediate circle included the painter Jasper Johns, the choreographer Merce Cunningham and the avant-garde composer John Cage. On the West Coast Edward Keinholz and Wallace Berman were creating artworks that would come to be called “Assemblage”—think collage on a large scale. In Paris, Arman, Jean Tinguley and Jacques de la Villeglé incorporated the debris of the city; junk and cast off commodities incorporated into artworks that became know as Nouveau réalism (New realism).

Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954-55 (dated on reverse 1954), encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric mounted on plywood, three panels, 42-1/4 x 60-5/8″ /107.3 x 153.8 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Canyon is more than an accumulation of debris, however. Note the skeins of paint, brushed, scribbled, clotted, dripping in the style of the abstract expressionists. Rauschenberg was also closely aligned with the New York School—particularly the older abstract expressionists—whose work he admired. But he nevertheless expressed a profound ambivalence towards this group: “There was something about the self-assertion of abstract expressionism that personally always put me off, because at that time my focus was as much in the opposite direction as it could be.”[3]

Robert Rauschenberg, Canyon (detail), 1959, oil, pencil, paper, metal, photograph, fabric, wood, canvas, buttons, mirror, taxidermied eagle, cardboard, pillow, paint tube and other materials, 207.6 x 177.8 x 61 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © 2014 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Rauschenberg’s self-conscious handling of paint intertwined with often-outrageous objects can be construed as parody. In this way, Canyon can be seen as a counter to the overblown rhetoric of abstract expressionism with its stress on heroic individualism and the formal purity of abstract art. The eagle (with its testicular appendage hanging below the frame)—like Jasper Johns’ American flag (see above) from the same period—may be an ironic commentary on heroic masculine identity and even cold-war era American power. As a gay artist during a deeply repressive era that sought to expel both the threat of communism and of homosexuality, Rauschenberg distanced himself from cultural orthodoxy.