Arts of the Islamic world: The medieval period: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter

Islamic art c. 900–1400

Court of the Lions, The Alhambra, Sabika hill, Granada, Spain, begun 1238 (photo: Tuxyso, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the period referred to as “medieval,” based on chronologies that were created to study the history and art history of western Europe, the Islamic world stretched from Europe and Africa to China. After the breakdown of the Abbasid Empire in the 9th–10th century C.E., the Islamic world was led by a diverse set of rulers adhering to different strands of Islam and speaking different languages. We are faced with a vast geography, a wide range of monuments and objects made for Muslim and non-Muslim patrons, by Muslim and non-Muslim artists. The arts of the Islamic world are thus not easily subsumed into one short essay.

Map of the Maghrib (Islamic West) (underlying map © Google)

The study of the medieval Islamic world sometimes divides the artistic production of the period into two geographic parts: the arts of the Islamic West (maghrib in Arabic, referring roughly to the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa, not including Egypt) and the Islamic East (mashriq in Arabic), referring to Egypt and what lies to the east of it.

Map of the Mashriq (Islamic East) (underlying map © Google)

Rivaling caliphates of the early period

Parts of the Iberian Peninsula (today’s Spain and Portugal) came under Muslim rule beginning in 711, when Tariq ibn Ziyad crossed the Strait of Gibraltar. After 755, al-Andalus (as the region was called in Arabic) was ruled by the Umayyads, who had lost control over the eastern Islamic world to the Abbasids in 750.

One of the major monuments surviving from this period is the Great Mosque of Córdoba, founded in 786 and expanded in several phases. It has served as a Christian cathedral since Córdoba was conquered by the king of Castile and Leon in 1236. The court of the Umayyads centered in Córdoba and Madinat al-Zahra also commissioned luxury objects including containers made of ivory, such as the Pyxis made by Khalaf and the Pyxis of al-Mughira.

Left: Khalaf, Pyxis, c. 966 (Umayyad dynasty, Spain), ivory with chased and nielloed silver-gilt mounts (Hispanic Society Museum and Library, new York); right: Pyxis of al-Mughira, AH 357/968 C.E. (possibly from Madinat al-Zahra), carved ivory with traces of jade, 16 x 11.8 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

With the Abbasids’ take over of the caliphate, the center of power of the Islamic world shifted to Iraq and Khurasan (where the Abbasid movement had originated). In order to remove themselves from what had been the center of Umayyad power—Damascus, and Greater Syria more broadly—the Abbasids established a new capital in Baghdad in 762, built as a round city with the palace at its center.

Artistic production shifted in this period, with new modes of production that moved away from the late antique aesthetics typical of the Umayyads. Trade played an important role in the development of Islamic art in this period—for instance, ceramics imported from Tang China inspired so-called splash ware produced in Iraq. Sea trade was crucial for the exchange with China, and direct evidence for it exists, for instance, in the Belitung shipwreck, the remains of a ship that sank in the 830s with a cargo of Tang ceramics shipped from China to West Asia.

The Umayyads declared themselves caliphs in 929, in direct rivalry with the Abbasids, who held the caliphate since 750, and were centered in present-day Iraq. In the early 10th century, the Fatimids, a Shi’ite dynasty that emerged from present-day Tunisia, conquered Egypt in 969 and made its new capital there, and also claimed the title of caliph. While direct conflict at times emerged between the Abbasids and Fatimids, especially as the Fatimids sought to expand their rule into Syria, the Umayyads did not seek to expand beyond their lands in the Maghrib. The Umayyad caliphate fell among succession struggles in 1031, and was succeeded by the so-called Taifa kingdoms, local dynasties centered in cities such as Zaragoza, Málaga, and Granada.

Maqsura and mihrab, Great Mosque of Tlemcen, Algeria, 1136 (photo: Archnet)

Dynasties in the Maghrib

Two subsequent dynasties emerging from among the Amazigh tribes of North Africa, the Almoravids and the Almohads came to control the parts of al-Andalus that remained under Muslim rule. The city of Tlemcen in present-day Algeria was founded by the Almoravids (under the name Tagrart); its Great Mosque, today mostly dating to 1136, displays intricate stucco work on its mihrab (prayer niche)—with a horseshoe arch evoking the Islamic architecture of al-Andalus—and maqsura.

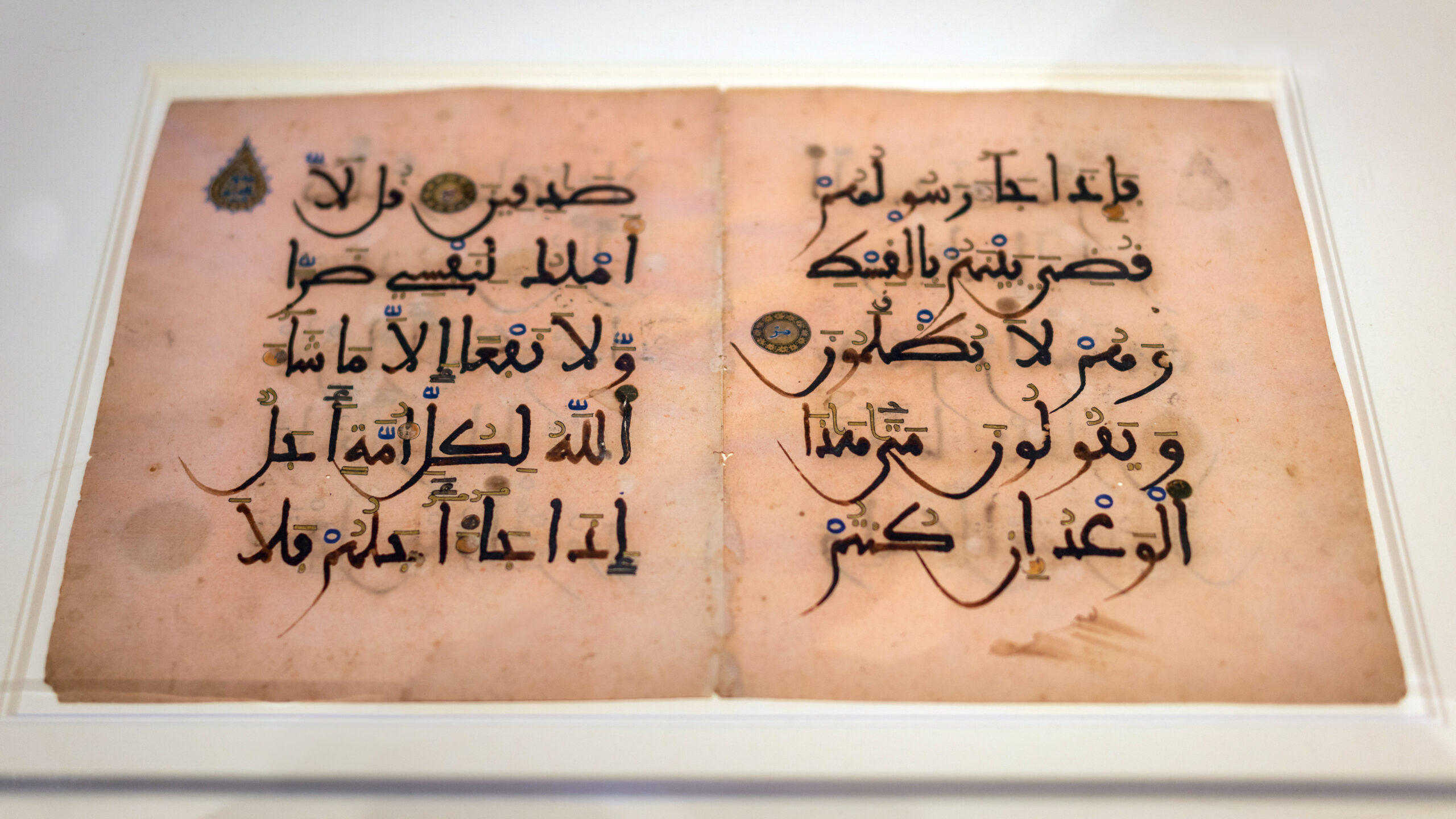

Bifolium from the Pink Qur’an, c. 13th century (Spain), ink, gold, silver, and opaque watercolor on paper, 31.8 x 50.2 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Over the course of the 11th to 13th centuries, Christian rulers from the northern part of Spain increasingly conquered territories under Muslim rule, a process often known as reconquista, a fraught term that emphasizes Christian re-capturing of territory. By the late 13th century, Muslim-ruled territory was limited to the Nasrid rulers centered in Granada. They were patrons of manuscripts, such as a magnificent Qur’an written on pink paper.

Façade of Comares Palace in the Alhambra, Granada, Spain, 14th century (photo: Jeff and Neda Fields, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In Granada, the Nasrids built their fortified palace city known as the Alhambra, where vast rooms and courtyards decorated with tiles, woodwork, and stucco carved with inscriptions of Arabic poetry, vegetal, and geometric motifs testify to the court’s splendor. Nasrid rule ended in 1492, when the rulers of Castile took Granada.

al-ʿAziz ewer, rock crystal, Fatimid dynasty, Cairo, 1001–10, with 16th-century gold and enamel mounts (Treasury of San Marco, Venice)

Dynasties in the Mashriq

Map of the Fatimid Caliphate (underlying map © Google)

Fatimids and their impact

The Fatimid ruled was centered in their palace city in what is now northern Cairo from 969 until 1174. Nothing remains of their palaces, but objects produced in this period such as jewelry and rock crystal, survive, as do religious monuments—not only mosques, but also churches for the Coptic Christian community, and the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat, for the Jewish community. The impact of Fatimid art is also seen in the coronation mantle made for the Norman kings of Sicily; the muqarnas ceiling of the Cappella Palatina in Palermo built for these Norman kings and which show paintings closely connected stylistically with images on Fatimid ceramics, woodwork, and the few surviving works on paper.

Samanid Mausoleum (sometimes called the Mausoleum of Ismail Samani), Bukhara, Uzbekistan, late 9th–early 10th century (photo: Elizabeth Macaulay, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Map of the Samanid dynasty at 943 (underlying map © Google)

Samanids, Ghaznavids, and Ghurids

One of the central developments of the 10th century was the conversion to Islam of a number of Turkic tribes in Central Asia, and their subsequent migration to regions from Afghanistan to Turkey (in present-day terms). One of these dynasties, the Samanids, are the patrons of one of the earliest surviving freestanding funerary monuments, the so-called Samanid Mausoleum in Bukhara, an undated building probably from the late 9th or early 10th centuries. Such funerary buildings, often domed structures, became widely used for rulers, their family members, and important religious figures.

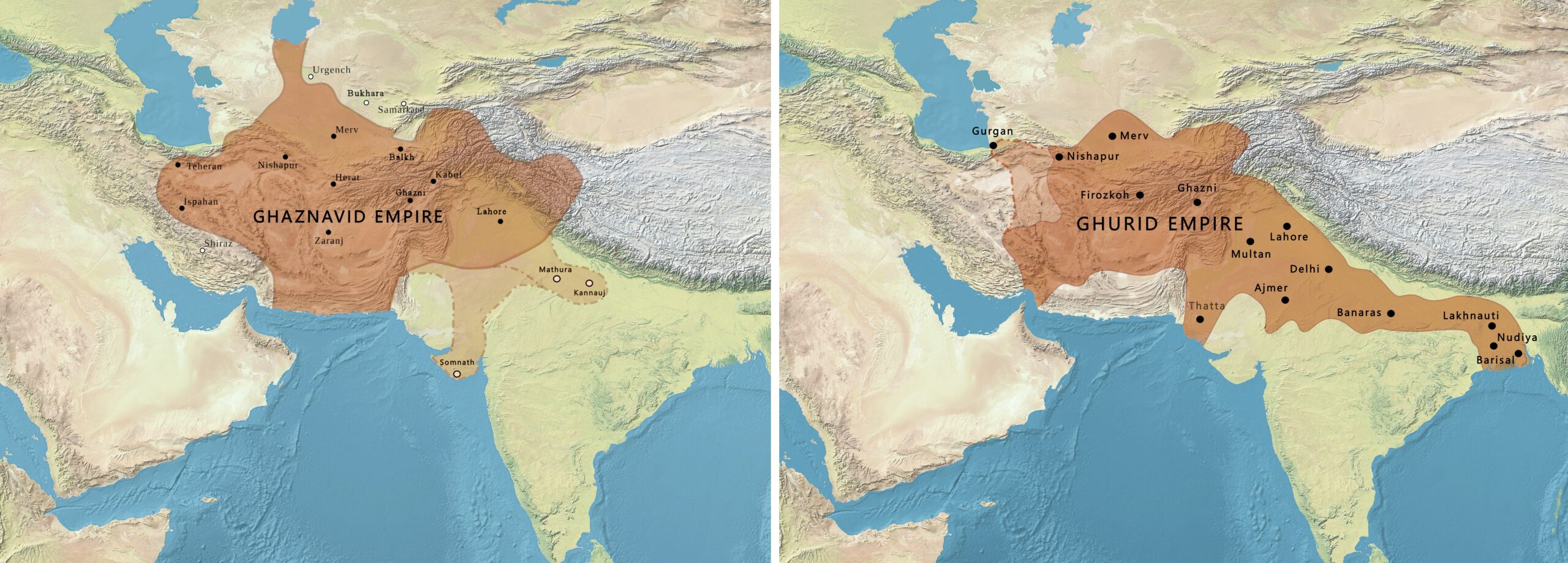

Maps of the Ghaznavid Empire (975–1187) (source: Schwartzberg Atlas, CC BY-SA 4.0) and Ghurid Empire (1175–1215) (source: Schwartzberg Atlas, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Ghaznavids ruled from 977 to 1186 in an area that extended from present-day Afghanistan into parts of Iran, and into Central Asia. Famously, Ferdowsi’s Shahnama, one of the major works of Persian literature, was dedicated to Mahmud of Ghazni. In the early 12th century, Mas’ud III commissioned a large palace complex in Ghazni, his summer capital, which was later abandoned; some of its rich architectural decoration, such as marble panels, were recovered in excavations.

Stone screen and prayer hall built by Qutb al-Din Aibak, courtyard of the Quwwat al-Islam mosque, begun c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Daniel Villafruela, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Ghurids, who emerged from central Afghanistan in the early 11th century eventually overcame the Ghaznavids. Like the Ghaznavids, they undertook raids into northern India, and were able to establish a permanent presence there. One of the major architectural monuments of sultanate India is the Qutb complex in Delhi, with elements dating to the late 12th century. Several sultanates were established in different regions of the Indian subcontinent, with a wide range of surviving monuments and objects, dating from the 12th to the 16th centuries.

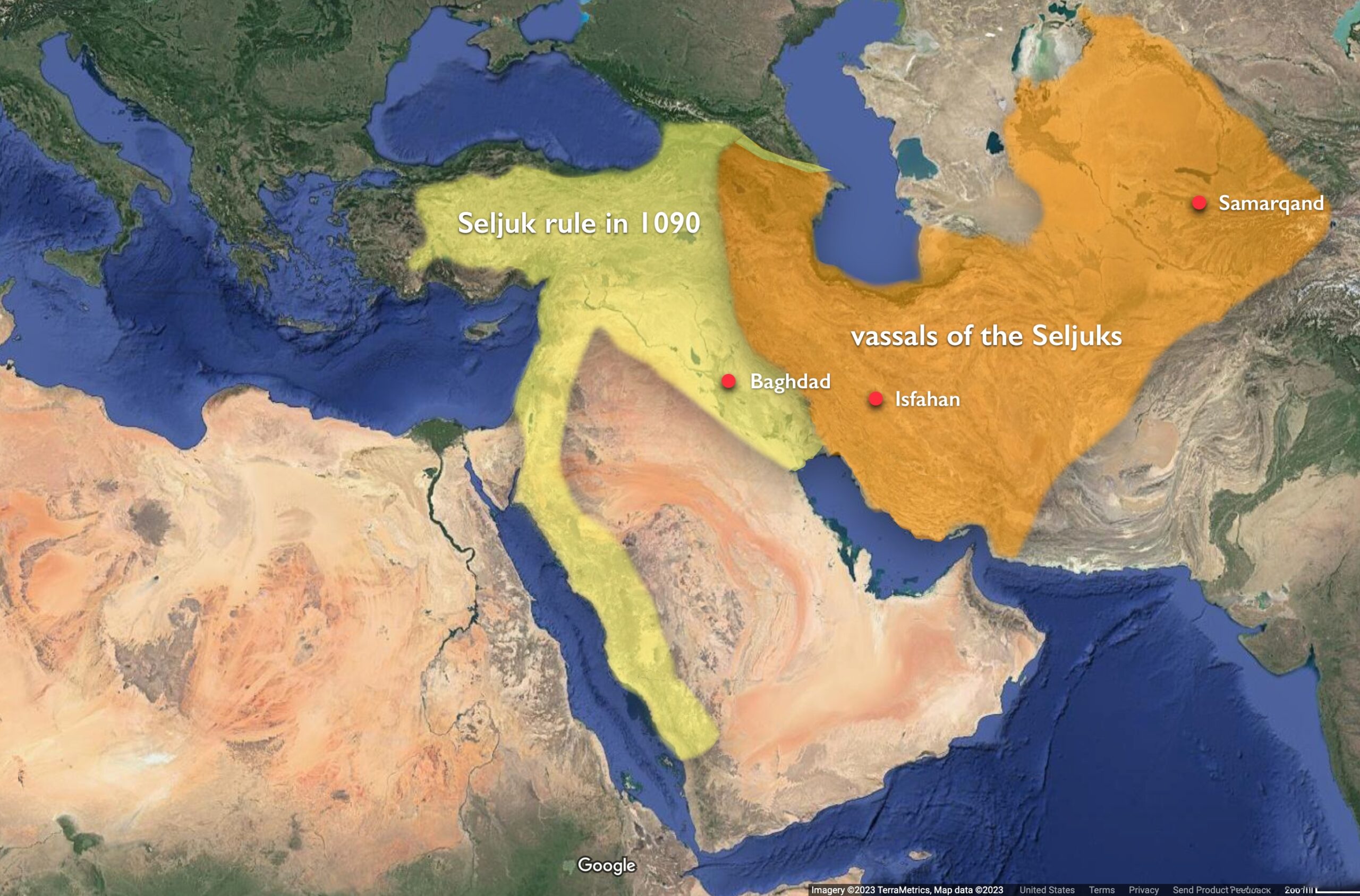

Seljuk rule in 1090 (underlying map © Google), adapted from Markus Hattstein and Peter Delius, Islam: Art and Architecture (Potsdam: H.F.Ullmann Publishing Gmbh, 2015)

Seljuqs, Buyids, and Ayyubids

The Seljuqs emerged from Central Asia as well and at times rivaled the Ghaznavids. Moving west-ward, the Seljuqs conquered Baghdad in 1055, and made themselves the protectors of the Abbasid caliph, who no longer had any actual political power. Like the Buyids, who had taken on a similar position since 945, the Seljuqs were the actual rulers. Taking on the title “sultan”, they both controlled and protected the caliph. Unlike the Buyids, who were Shi’i Muslims, the Seljuqs were Sunni. Seljuq rule expanded from Iran into Anatolia, a region they captured from the Byzantine Empire in the late 11th century. In Iran, they expanded and transformed the Great Mosque of Isfahan. Palace architecture does not survive, but stucco guardian figures have been connected to Seljuq royal monuments. Production of luxury ceramics expanded in the city of Kashan, where complex wares such as mina’i and lustre were produced by artists, some of whom signed their names like Abu Zayd who lived in the late 12th century.

Abu Zayd, bowl with a majlis scene by a pond, 1186 C.E. (Kashan, Iran), stone paste, glazed in opaque turquoise, polychrome in-glaze- and overglaze- painted, 21.6 cm diameter (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The Seljuqs, and successor dynasties ruling in Anatolia, but especially Greater Syria, were part of a push-back against the Crusaders (European Christians who conquered Jerusalem in 1099 in an act of faith-based war to claim holy sites in the city). The most famous Muslim ruler fighting the Crusaders was Salah al-Din ibn Ayyub, known in the West as Saladin, who ruled Egypt and Syria since 1174 and took Jerusalem back in 1189. The dynasty he founded, known as the Ayyubids, ruled Egypt and Syria until 1250, when the Mamluks took over.

Left: Candlestick base attributed to al-Malik al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun, first half of 14th century (Egypt), brass with silver inlay, 21.1 x 33.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); right: Glass lamp for mosque of sultan Hassan, Egypt, 1354–61, enameled and gilt glass, 35 cm high (Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon)

Mamluks and Ilkhanids

The Mamluks have their roots in the practice of using enslaved soldiers, current since the Abbasid period, but still used by the Ayyubids. Once the enslaved Mamluks overthrew their Ayyubid masters, they created their own system of rule. Succession was hardly ever dynastic but rather, rivaling military leaders succeeded each other, with a few exceptions of rule passing from father to son. Ruling from the 1250s until the Ottoman conquest of Cairo in 1517, the Mamluks fostered the production of luxury Qur’ans and bindings, of metalwork ranging from candlesticks to basins, and glass lamps for religious monuments. The Mamluk sultans and their affiliates were prolific patrons of architecture in cities such as Cairo, Damascus, Aleppo, and Jerusalem.

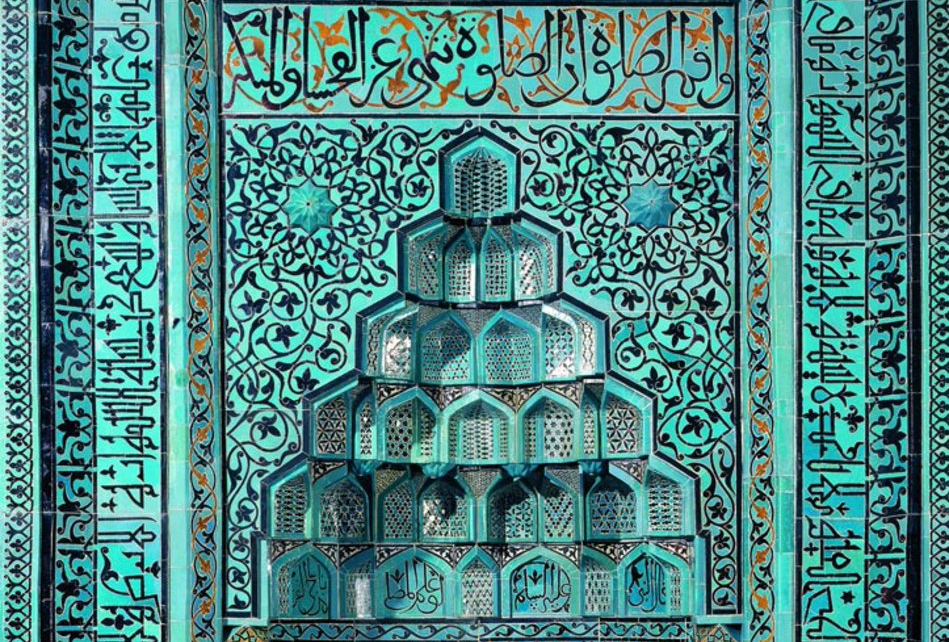

Starting in the 1260s, the Mamluks rivaled with the Ilkhanids, the Mongol rulers of Iran, who were similarly prolific patrons. With the Mongol conquest beginning in the 1220s, connections were created between the Islamic world and East Asia, especially China which also came under Mongol rule, and where Muslim communities were present especially in coastal port cities. At the artistic level, the impact was most strongly felt in the arts of the book, which saw a huge increase in production beginning in the early 14th century. Religious architecture in Iran continued to be produced with elements similar to those used earlier, and tile mosaic as a technique of architectural decoration reached new heights in the second half of the 14th century.

Go deeper

Read an introductory essay

/1 Completed

Learn more about the rivaling caliphates of the early period

The Great Mosque of Córdoba: This building has a rich history as one of the oldest structures remaining from the Umayyad rule of al-Andalus.

Read Now >

Khalaf, Pyxis: This exquisitely sculpted ivory pyxis was created in Umayyad Spain by the artist Khalaf.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Explore the dynasties in the Maghrib

Camel from San Baudelio de Berlanga, Spain: What a camel in New York reveals about medieval Spain

Read Now >

Great Mosque of Tlemcen: Located in Algeria, the architectural decoration of the Great Mosque recalls that in al-Andalus.

Read Now >

Bifolium from the Pink Qur’an: The pink-dyed pages and gilded decoration indicate that this Qur’an may have belonged to a royal or noble patron.

Read Now >

The Alhambra: This city within a city is famed for its three highly decorative palaces and their equally elaborate gardens.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Read about Fatimid art and its impact

Gold pendant with inset enamel decoration: The cloisonné enamel-work on this pendant speaks to the connections between the Fatimid dynasty and the Byzantine Empire.

Read Now >

Rock crystal ewer, San Marco: This vessel is a unique testament to the height of rock crystal production at the court of the Fatimid caliphs.

Read Now >

The Ben Ezra Synagogue, Fustat, Egypt: Many members of the Jewish population remained in Fustat under the Fatimid dynasty.

Read Now >

Coronation Mantle: Muslim artisans produced this luxury robe for the Norman king in Sicily.

Read Now >

The Cappella Palatina: The Cappella Palatina’s architecture and decoration featured styles and crafts culled from Sicily and Southern Italy itself, Byzantium, Fatimid Egypt, the Maghrib, and the Crusader Levant.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Learn more about the Samanids, Ghaznavids, and Ghurids

The Samanid Mausoleum, Bukhara: Built for one of the members of the Samanid dynasty, the tomb is one of the earliest surviving examples of funerary architecture in the Islamic world.

Read Now >

The Qutb complex and early Sultanate architecture: The Qutb complex and its monuments are important for understanding the early part of the Delhi Sultanate.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Explore the art and architecture of the Seljuqs, Buyids, and Ayyubids

The Great Mosque (or Masjid-e Jameh) of Isfahan: Built in the center of the Seljuq capital, the mosque provides a tranquil space from the hustle and bustle of the city.

Read Now >

Two Royal Figures: Carved and molded from stucco, these figures may have once guarded a Seljuq reception hall.

Read Now >

Abu Zayd, Bowl with a Majlis Scene by a Pond: Abu Zayd’s ceramics reveal the distinctive combination of literary and visual worlds in 12th-century Iranian ceramics.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Learn about the Mamluks and Ilkhanids

A Mamluk candlestick base: Crafted for the sultan, this candlestick base represents the height of luxury at the Mamluk court.

Read Now >

Madrasa and Friday Mosque of Sultan Hasan, Cairo: The mosque-madrasa-funerary complex of the Mamluk Sultan Hasan has been considered one of the greatest mosque complexes ever built.

Read Now >

A glass lamp from sultan Hassan’s mosque and madrasa: This lamp would have shone brilliantly to illuminate God’s divine light and the sultan’s supreme authority.

Read Now >

Bahram Gur in a Peasant’s House: Illustrated books, like this Shahnama, flourished during a cultural revival that took place under the Ilkhanids.

Read Now >

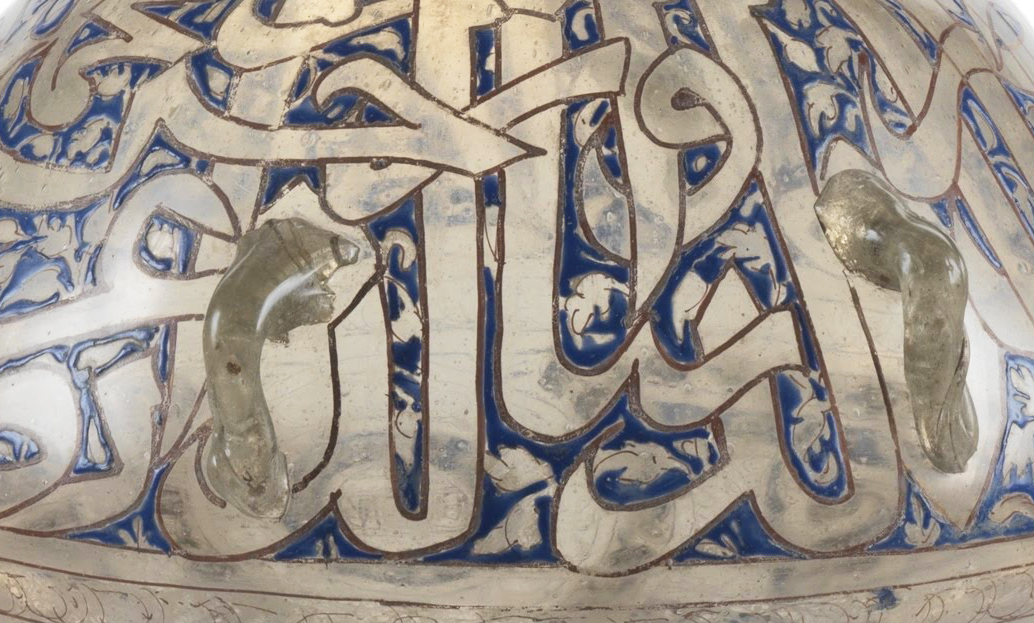

Mihrab from Isfahan (Iran): The vibrant blue tiles on this mihrab are a distinct feature found throughout the architecture in Isfahan.

Read Now >/6 Completed

Key questions to guide your reading

How do local circumstances affect the artistic production in large empires?

What is the role of cultural exchange in the medieval Islamic world?

How do newly emerged dynasties adopt or change the artistic landscapes of their lands?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow do local circumstances affect the artistic production in large empires?

What is the role of cultural exchange in the medieval Islamic world?

How do newly emerged dynasties adopt or change the artistic landscapes of their lands?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Caliphate

Maghrib

Mashriq

Shi’ite

Sunni

Amazigh

maqsura

reconquista

muqarnas

Learn more

Sultanate art and architecture, an introduction

Ladan Akbarnia, et al., The Islamic World: A History in Objects (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018).

Ali Asgar Husamuddin Alibhai, “A Tale of Two Port Cities. Al-Mahdiyya, Palermo, and the Timber Trade of the Medieval Mediterranean,” Convivium, volume 10 (2023), pp. 46–67.

Jonathan Bloom and Sheila Blair, The Art and Architecture of Islam, 1250–1800 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994).

Jonathan Brack, “What a 14th-Century Image of the Prophet Muhammad tells us about Islamic and Mongol Cultural Exchange,” Ajam Media Collective, volume 15 (2024).

Finbarr Barry Flood and Gülru Necipoğlu, editors, A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture, 2 volumes (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2017).

Sarah M. Guérin, “Forgotten Routes? Italy, Ifrīqiya and the Trans- Saharan Ivory Trade,” Al-Masaq: Journal of the Medieval Mediterranean, volume 25, number 1 (2013), pp. 70–91.

Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar and Marilyn Jenkins-Madina, Islamic Art and Architecture 650–1250, Pelican History of Art series (New Haven: Yale University Press 2001).

Jennifer A. Pruitt, Building the Caliphate: Construction, Destruction, and Sectarian Identity in Early Fatimid Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020).

D. Fairchild Ruggles, “Mothers of a Hybrid Dynasty: Race, Genealogy, and Acculturation in al-Andalus,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, volume 34, number 1 (2004), pp. 65–94.

Abbey Stockstill, “A Tale of Two Mosques: Marrakesh’s Masjid al-jamiʿ al-Kutubiyya,” Muqarnas, volume 35 (2018), pp. 65–82.

Suzan Yalman, “Ala al-Din Kayqubad Illuminated: A Rum Seljuq Sultan as Cosmic Ruler,” Muqarnas, volume 29 (2012), pp. 151–86.