Courtyard, The Great Mosque or Masjid-e Jameh of Isfahan (photo: AlGraChe, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Most cities with sizable Muslim populations possess a primary congregational mosque. Diverse in design and dimensions, they can illustrate the style of the period or geographic region, the choices of the patron, and the expertise of the architect. Congregational mosques are often expanded in conjunction with the growth and needs of the umma, or Muslim community; however, it is uncommon for such expansion and modification to continue over a span of a thousand years. The Great Mosque of Isfahan in Iran is unique in this regard and thus enjoys a special place in the history of Islamic architecture. Its present configuration is the sum of building and decorating activities carried out from the 8th through the 20th centuries. It is an architectural documentary, visually embodying the political exigencies and aesthetic tastes of the great Islamic empires of Persia.

Street view of the Grand Bazaar of Isfahan with the Great Mosque dome in the distance (photo: Saif Alnuweiri, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Another distinctive aspect of the mosque is its urban integration. Positioned at the center of the old city, the mosque shares walls with other buildings abutting its perimeter. Due to its immense size and its numerous entrances (all except one inaccessible now), it formed a pedestrian hub, connecting the arterial network of paths crisscrossing the city. Far from being an insular sacred monument, the mosque facilitated public mobility and commercial activity, thus transcending its principal function as a place for prayer alone.

The mosque’s core structure dates primarily from the 11th century, when the Seljuq Turks established Isfahan as their capital. Additions and alterations were made during Il-Khanid, Timurid, Safavid, and Qajar rule. An earlier mosque with a single inner courtyard already existed in the current location. Under the reign of Malik Shah I and his immediate successors, the mosque grew to its current four-iwan design. Indeed, the Great Mosque of Isfahan is considered the prototype for future four-iwan mosques.

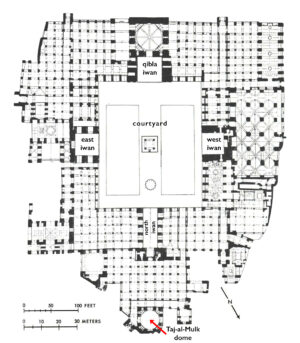

Plan of the mosque, drawn by Eric Schroeder, Architectural Survey, American Institute for Persian Art & Archaeology, 1931

Linking the four iwans at the center is a large courtyard open to the air, which provides a tranquil space from the hustle and bustle of the city. Brick piers and columns support the roofing system and allow prayer halls to extend away from this central courtyard on each side. Aerial photographs of the building provide an interesting view; the mosque’s roof has the appearance of “bubble wrap” formed through the panoply of unusual but charming domes crowning its hypostyle interior.

Dome with oculus in the hypostyle prayer hall, Great Mosque or Masjid-e Jameh of Isfahan (photo: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0)

View of the south iwan from the prayer hall (photo: AlGraChe, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

This simplicity of the earth-colored exterior belies the complexity of its internal decor. Dome soffits (undersides) are crafted in varied geometric designs and often include an oculus, a circular opening to the sky. Vaults, sometimes ribbed, offer lighting and ventilation to an otherwise dark space. Creative arrangement of bricks, intricate motifs in stucco, and sumptuous tile-work (later additions) harmonize the interior while simultaneously delighting the viewer at every turn. In this manner, movement within the mosque becomes a journey of discovery and a stroll across time.

Given its sprawling expanse, one can imagine how difficult it would be to locate the correct direction for prayer. The qibla iwan on the southern side of the courtyard solves this conundrum. It is the only one flanked by two cylindrical minarets and also serves as the entrance to one of two large, domed chambers within the mosque.

Muqarnas, south iwan of the Great Mosque or Masjid-e Jameh of Isfahan (photo: youngrobv, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Similar to its three counterparts, this iwan sports colorful tile decoration and muqarnas or traditional Islamic cusped niches. The domed interior was reserved for the use of the ruler and gives access to the main mihrab of the mosque.

Interior decoration of Taj-al-Mulk (north) dome (photo: Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The second domed room lies on a longitudinal axis right across the double-arcaded courtyard. This opposite placement and varied decoration underscore the political enmity between the respective patrons; each dome vies for primacy through its position and architectural articulation. Nizam al-Mulk, vizier to Malik Shah I, commissioned the qibla dome in 1086. But a year later, he fell out of favor with the ruler and Taj al-Mulk, his nemesis, with support from female members of the court, quickly replaced him. The new vizier’s dome, built in 1088, is smaller but considered a masterpiece of proportions.

When Shah Abbas I, a Safavid dynasty ruler, decided to move the capital of his empire from Qazvin to Isfahan in the late 16th century, he crafted a completely new imperial and mercantile center away from the old Seljuq city. While the new square and its adjoining buildings, renowned for their exquisite decorations, renewed Isfahan’s prestige among the early modern cities of the world, the significance of the Seljuq mosque and its influence on the population was not forgotten. This link amongst the political, commercial, social, and religious activities is nowhere more emphasized than in the architectural layout of Isfahan’s covered bazaar. Its massive brick vaulting and lengthy, sinuous route connects the Safavid center to the city’s ancient heart, the Great Mosque of Isfahan.

Additional resources

Masjid-i Jami’ (Isfahan) essay on Archnet.

Read a Reframing Art History chapter about “Framing Islamic Art.”