Mosques, tombstones, textiles, and murals are only a few examples of the art and architecture created on the Indian subcontinent in the sultanates. The sultanates were areas governed by Muslim sultans that were originally unified as the Delhi sultanate but would eventually fracture into independent states, and whose art and architecture was innovative and eclectic, drawing on sources from across Asia. For some sultanates, the Indian Ocean trade network, which connected East Africa, the Arabian peninsula, the south coast of Iran, the Indian subcontinent, and south east Asia, allowed for the easy mobility of objects and ideas across this vast geography. For others, overland trade and shifting political affiliations would facilitate mobility.

By the fourteenth century, the Delhi sultanate had expanded considerably, extending all the way south to encompass the Deccan plateau.

Map of the sultanates (Gujarat, Sindh, Jaunpur, Bengal, and the Bahmani, sultanate), c. 1400; also indicated are the cities of Delhi and Bidar (underlying map © Google)

Their hold over this vast empire, however, was often tenuous and multiple groups—in Gujarat, northern Karnataka, Jaunpur, Bengal, and Sindh—broke away to form independent sultanates.

The courtyard of the Quwwat-al-Islam mosque, c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi. In the foreground are pillars of the colonnaded walkway and in the background is the 12th-century screen and prayer hall. (photo: Indrajit Das, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The 238 foot tall Qutb minar in the background, c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Indrajit Das, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The arts of these breakaway states were influenced by the artistic traditions of the Delhi sultans. One of the earliest and most influential examples of architecture from the Delhi sultanate is the Qutb complex in Delhi. Key elements of the complex, notably the architectural stone screen in front of the prayer hall and the towering Qutb minar (tower), would be replicated or referenced in monuments across the Subcontinent. Sultanate arts did not simply replicate the architecture of Delhi, however, they were also informed by local styles, materials, and practices resulting in an astonishing variety of artistic products. It is the art and architecture produced between the 14th and 16th centuries in these independent states that this essay focuses upon.

Gujarat

The Muzaffarid dynasty ruled over the western Indian region of Gujarat. The region had long been home to a Muslim community, a result of the Indian Ocean trade network.

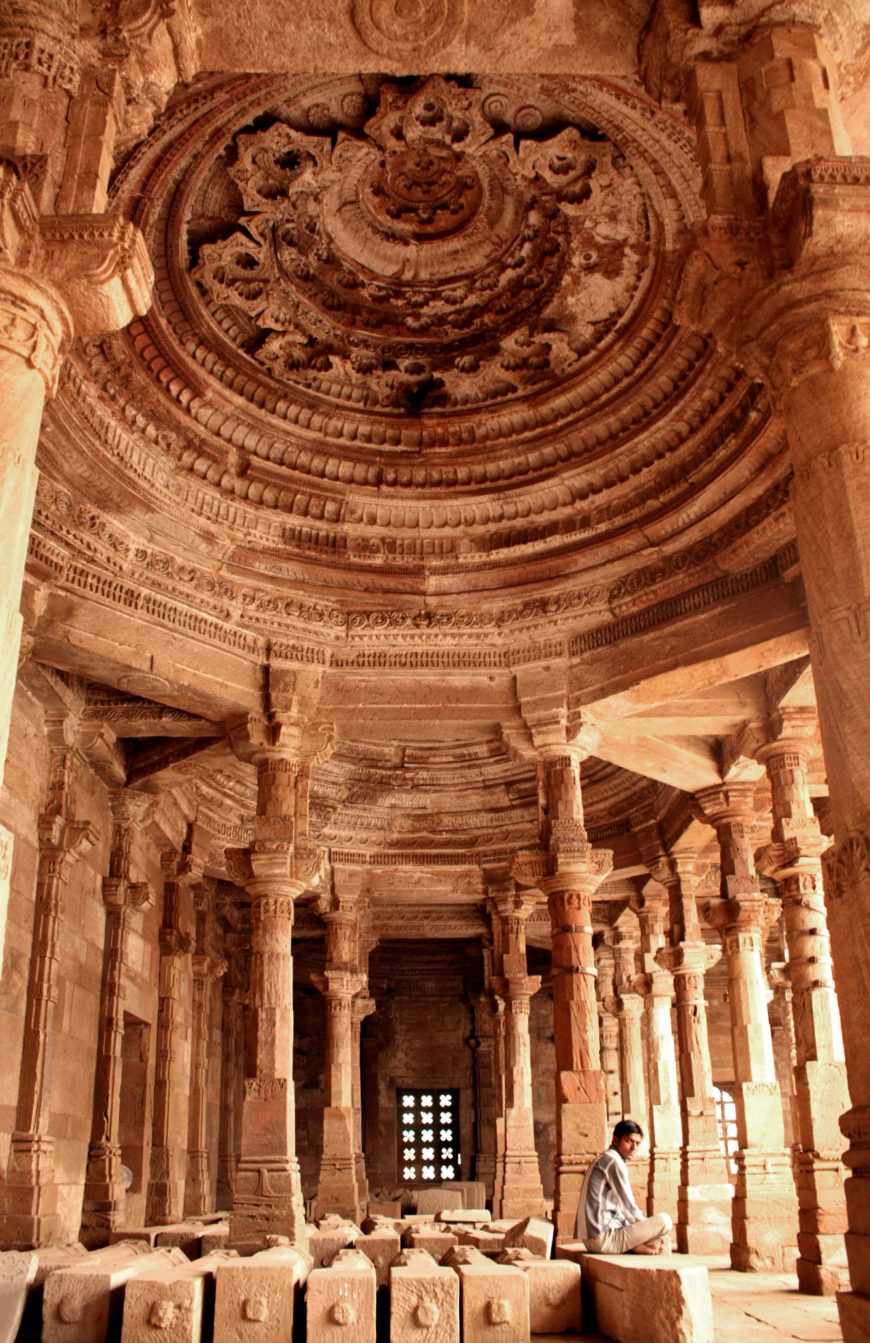

The earliest evidence of these settlements is a small cluster of funerary and religious monuments in Bhadresvar dating from the twelfth century (not pictured here). The buildings are stylistically connected to Hindu and Jain temples in the area, as demonstrated by their stone domes finely carved on the interior with lotus motifs and built using corbeling construction techniques.

Example of Maru-Gurjara architecture. Stone dome with lotus motif in the entrance corridor looking towards the eastern wall, Friday mosque of Khambayat (also known as Cambay), 14th century, India (photos: Mufaddal Abdul Hussain, CC BY-SA 3.0)

This style of architecture is referred to as Maru-Gurjara architecture and would continue to be employed in later Gujarati monuments. [1]

Example of Maru-Gurjara architecture. View from the courtyard of the Friday mosque of Khambayat (also known as Cambay), 14th century, India (photos:

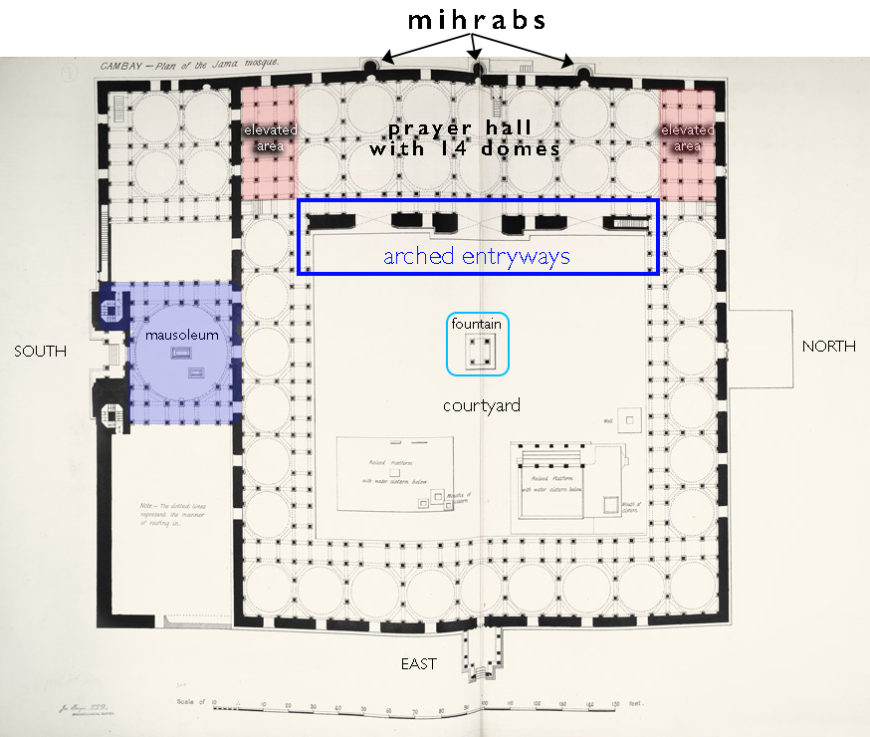

Plan of the Friday mosque and tomb complex of Khambayat (also known as Cambay). The Tomb complex of Umar al-Kazeruni is located on the south side, with the mausoleum in the center.

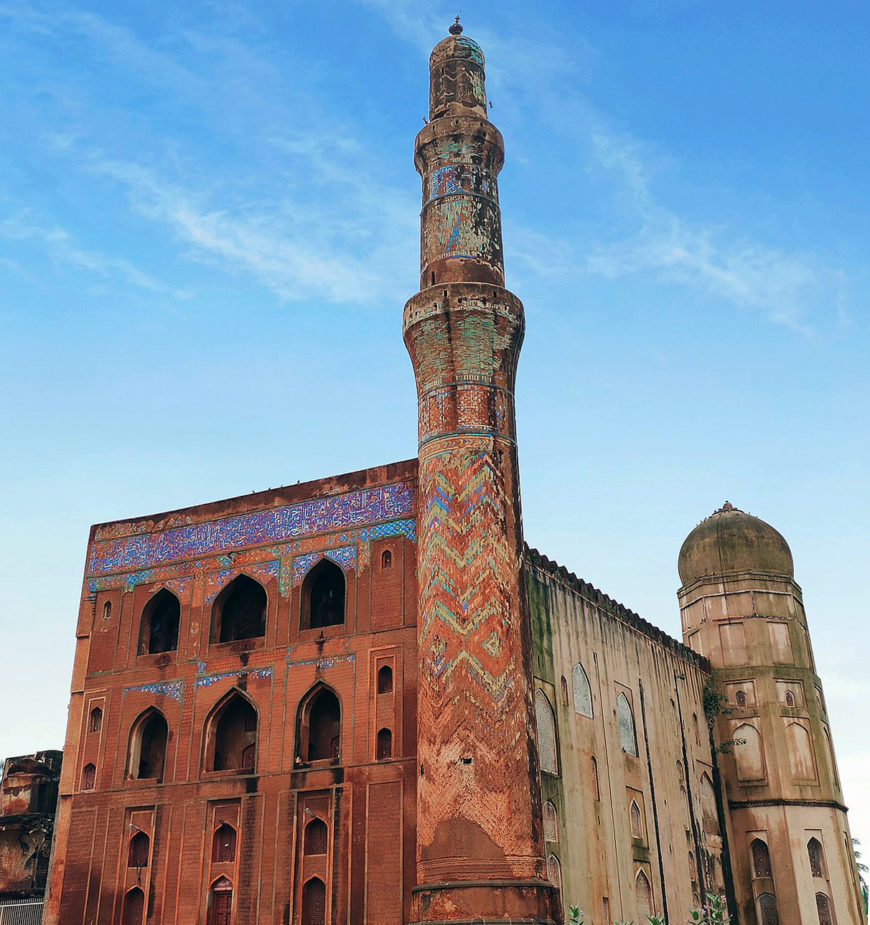

Friday mosque of Khambayat and adjoining tomb complex

A spectacular example of Maru-Gurjara architecture is the Friday mosque of Khambayat (also known as Cambay) and the adjoining tomb of Umar al-Kazeruni (a powerful merchant originally from Iran who died in 1333).

The Friday mosque is planned as a typical hypostyle (multi-column) courtyard mosque, common throughout the Islamic world, with a central courtyard surrounded by colonnades on three sides and the prayer hall on the fourth, western side. Three arched entrances lead into the prayer hall which is covered by fourteen corbelled domes. On each end of the hall are elevated and screened areas (the areas in pink on the plan), thought to be muluk khanas (king’s chamber) and women’s galleries.

The prayer hall is marked by five mihrabs, three of which are in the principal hall and two in each of the closed sections (not shown here). [2] The three main mihrabs are visible on the exterior wall by projecting semi-circular buttresses (as seen in the plan).

Tomb complex of Umar al-Kazeruni

Mausoleum of the tomb complex of Umar al-Kazeruni, attached to the Friday mosque of Khambayat (also known as Cambay), 14th century, India (photo: Mufaddal Abdul Hussain, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The tomb complex of Umar al-Kazeruni was attached to the south wall of the mosque. The complex includes a small funerary mosque which is aligned with the Friday mosque’s prayer hall and a large courtyard on the east.

The mausoleum includes the cenotaphs of al-Kazeruni and of his wife Bibi Fatima, which are set within an octagonal space surrounded by a columned gallery of three stories.

A dome originally covered the structure but a devastating earthquake in 1819 caused it to collapse (and so now we can see into the space from the roof). Two minarets are also supposed to have topped the monumental entrance to the tomb complex, neither of which survive.

The two marble cenotaphs located in the center of the octagonal gallery are finely carved with multiple inscriptions and vegetal designs. Looking carefully at al-Kazeruni’s headstone (below), it is notable that multiple calligraphic styles are employed, including an elaborate knotted and floriated kufic basmala.

Omar bin Ahmad Al Kazaruni’s cenotaph in the Jami Masjid (Mosque) Khambhat (Cambay), c. 1333 century, India, photographic print by Henry Cousens from 1885 (British Library). For a close up and to see the sides, use this Google Street View

Another notable feature of the cenotaph is the repeated use of a lamp motif, where a cusped arched niche is carved into the marble with a lamp hanging from a chain in the center of the arch (seen on the left side in the photo above). This motif was popular in gravestones and architectural decoration in the Islamic world at the time and is likely a reference to the Light Verse in the Qur’an (24:35) which likens the light of God to that of a lamp hanging in a niche.

Patronage and mercantilism

The patron of the mosque, Dawlatshah Muhammad al-Butihari, held a variety of administrative positions and was closely connected to the ports of Gujarat while al-Kazeruni held the official title malik al-tujjar (prince of merchants). His burial next to the mosque, a highly desirable location for pious Muslims, as well as his title, emphasize his significance. Merchants were particularly important in Gujarati port cities such as Khambayat, because of how essential they were in the city’s Indian Ocean trade.

Little is known about the tombstone, except that it was shipped from Aden to the British Museum in 1840. Tombstone, c. 15th century, marble, from Aden, Yemen, made in India, 117 x 86 (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The global reach of Gujarati objects across the Indian Ocean suggests how central the region was to the wider oceanic world. Among these objects were marble carved tombstones and architectural elements that traveled to numerous locations stretching from Kilwa in modern day Tanzania to Pasai in northern Sumatra. One of these tombstones, now in the British Museum, is among a series of grave memorials exported to the southern Arabian peninsula (now Oman and Yemen).

Two gravestones, made on June 8, 1311 for the tomb of Nur al-Din Ibrahim, governor of Dhofar, in Oman, carved marble, found in Dhofar, Oman, made in Khambhat, Gujarat, India. Left: headstone, 108.3 x 46.2 cm (Victoria & Albert Museum); right: footstone, 127 x 48 cm (Victoria & Albert Museum)

A pair of gravestones in the Victoria and Albert Museum which were found in Dhofar in Oman adds further context. The pair were the headstone and footstone of the grave of al-Malik al-Watiq Nur al-Din Ibrahim ibn al-Malik al-Muzaffar, a son of the Rasulid sultan who served as a governor of Dhofar. The Rasulid dynasty, who ruled over Yemen and parts of Oman between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, benefitted from taxes they levied on merchants involved in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean trade.

Brazier of Rasulid Sultan al-Malik al-Muzaffar Shams al-Din Yusuf ibn ‘Umar, second half 13th century, brass; cast, chased, and inlaid with silver and black compound, probably made in Egypt, 35.2 x 39.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Their wealth allowed them to commission multiple luxury objects, including the Cambay marble carvings and inlay metalwork from Mamluk Egypt, such as a brazier (portable heater or grill) made for the second Rasulid sultan, Al-Malik al-Muzaffar Shams al-Din Yusuf ibn Umar.

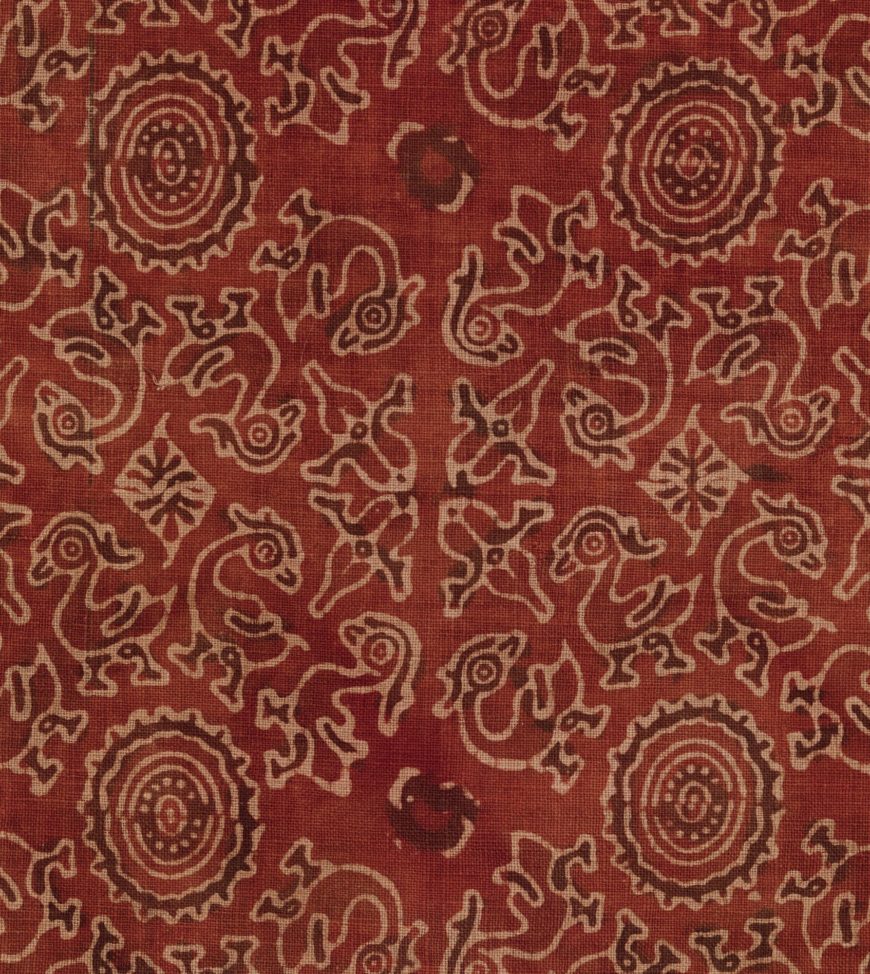

Textile with sacred goose (hamsa) design, 15th–early 16th century, cotton, block-printed and mordant-dyed, India (Gujarat, for Indonesian Market), 103.5 × 481.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Textile with sacred goose (hamsa) design (detail), 15th–early 16th century, cotton, block-printed and mordant-dyed, India (Gujarat, for Indonesian Market), 103.5 × 481.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Other coveted items from Gujarat were block-printed textiles. The textiles were printed with a variety of designs. Some fragments were printed with hamsa (sacred geese) that faced each other arranged around a design of concentric circles.

Other fragments include bands of Arabic inscriptions in the style of tiraz fabrics produced in the royal workshops of the Abbasid and Fatimid dynasties. [3] The finds of hundreds of fragments suggest a prolific trade, while the specific designs indicate how well informed Gujarati artisans must have been of different consumers.

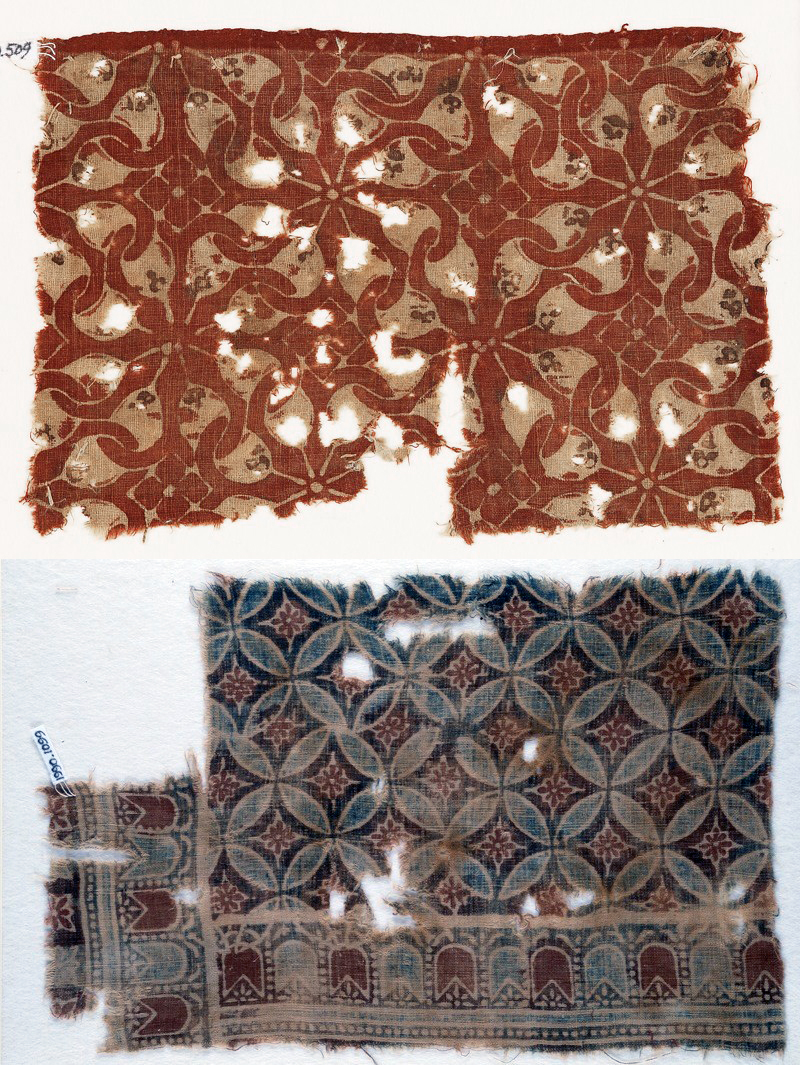

Above: Textile fragment with interlocking spirals or rosettes, mid-13th century, block-printed cotton, 26 x 17.5 cm, made in Gujarat, India (Ashmolean Museum); below: Textile fragment with linked circles and rosettes, 2nd half of the 13th century–1st half of the 14th century, cotton, possibly block-printed, made in Gujarat, India, 35 x 23.5 cm (Ashmolean Museum)

An interesting result of this trade is the transmission of designs through textiles and their influence upon architectural decoration, as seen in the murals of the Amiriya complex in Yemen.

Amiriya Madrasa murals, 1504, tempera, Rada’a, Yemen (photo: CCARoma), view in Google Street view

The upper walls and interior ceiling of the structure are entirely covered by murals using an incredible variety of patterns and calligraphy. Looking closely at the decorations, it is clear that some of the patterns mimic those found in the Gujarati textiles, suggesting that the painters of the murals might have been inspired by these and similar fabrics.

Bidar and the Bahmanis

The importance of merchants extended beyond the goods they carried. We see this in the inhabitants of the city of Bidar, the third capital of the Bahmani dynasty, which was founded by Ahmad I in 1430 in order to distance himself from his predecessors. Their rule would be characterized by an interest in building connections with foreign powers, such as the powerful Timurids of Central Asia as well as welcoming immigrants from Persian-speaking regions. Bahmani cosmopolitan courtly culture would also be reflected in their architectural patronage.

The capital city of Bidar included various features inspired by the architecture of the Timurid courts, including the motif of walking tigers or lions with a rising sun behind their backs executed in glazed tiles on the spandrels of two surviving portals in the palace complex (unfortunately, we are not able to show this currently). The motif, also known as shir o khurshid, had a long history of use in Iran and is known from the twelfth century onwards on multiple objects, including on the walls of the Aq Saray palace of Timur in Shahrisabz (it no longer survives there, but an earlier version can be seen here; the palace is shown below). Originally connected with astrological symbolism, the motif also came to be closely associated with royalty through its repeated use as dynastic and state symbol.

Madrasa of Mahmud Gawan

An important figure in Bidar was Mahmud Gawan, an Iranian immigrant who traded Arabian war horses and was recruited by the Bahmani sultan Ahmed II for his knowledge of the Persian-speaking world. Not only was Gawan well versed in Persian cultural traditions but he also maintained a vast network of contacts with scholars, poets, and princes, attested by over a hundred surviving letters penned by him. Like al-Kazeruni, Gawan was also titled malik al-tujjar and held the additional title of wakil al-sultanat (chief minister).

Madrasa of Mahmud Gawan, 15th century, Bidar, India (photo: Prasannasindol, CC BY-SA 3.0), see in Google Street view

Mahmud Gawan commissioned monuments connecting Bidar with Central Asia and Iran. He personally supervised the construction of a madrasa (religious school) in 1471–72. It is a large, three-story building, the southeastern parts of which were destroyed in 1696 (possibly due to a lightning strike or an explosion of gunpowder stored in the building). The original main entrance was in the center of the eastern section and led into a courtyard with iwans on each side.

Madrasa of Mahmud Gawan, 15th century, Bidar, India (photo: Bindaas Madhavi, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The use of the 4-iwan plan was fairly uncommon in India but is known to us from multiple examples in Timurid regions, such as the Ghiyathiya madrasa in Khargird, Khurasan. [4]

The exterior of the building is covered with tiles that form geometric patterns and bands of inscriptions. The decoration follows two techniques: tile mosaic employing monochrome glazed tiles that are cut to fit a pattern, and underglaze painted tiles where the design is painted onto the tile and then glazed and fired.

These techniques as well as the particular style of the calligraphic inscriptions in which the text is executed in white thuluth script set against a dark blue background with a scrolling vine of turquoise, occasionally marked by yellow and green flowers, are yet another example of Timurid affiliations.

Aq Saray Palace from the north, after 1380, Shakhrisabz, Uzbekistan (photo: Ymblanter, CC BY-SA 4.0), see Google street view

These same sorts of tiles cover the façade of Aq Saray palace of Timur. The multiple references suggest that Gawan strongly desired to make a clear visual connection between his architectural patronage and that of the Timurids, in keeping with Bahmani interests in the Timurids as well as his own Iranian background.

Jaunpur

Another breakaway state of the Delhi sultanate was that of the Sharqis of Jaunpur, established in 1398. The Sharqis were prolific patrons of the arts and their building commissions included the Atala mosque (discussed below), the Friday Mosque of Jaunpur, the Jhanjri mosque, Khalis Mukhlis, and Lal Darwaza—all built in the fifteenth century.

Atala Mosque, Jaipur, India (photo: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0), see in Google Street view

Pillared hall on the first floor side arcade, Atala Mosque, Jaipur, India (photo: Varun Shiv Kapur, CC BY 2.0)

Atala mosque

Mobility played a key role in Jaunpur’s architectural splendor. Following Timur’s invasion of Delhi in 1398, many scholars, artists, and craftsmen fled to Jaunpur. These artists played a critical role in the first building commissioned by the Sharqis, the Atala mosque. This mosque, with its colonnaded halls set around a central courtyard with four arched entrances and a massive propylon (a towering arched entrance rising 23 feet off the ground), would become the template for future Jaunpur mosques. The slight batter of the mosque’s walls and its layout have led scholars to connect the Atala with the Begampuri mosque in Delhi and with the architectural style of the Tughluq dynasty.

Monumental portal, Bibi Khanum mosque, built 1398–1405, Samarqand, Uzbekistan (photo: Arian Zwegers, CC BY 2.0), see in Google Street view

While Tughluq architecture certainly inspired some elements of the mosque, other features such as the propylon were drawn from a variety of sources, including the monumental portal of the Bibi Khanum mosque in Samarqand, emphasizing how inventive Sharqi architecture was in adapting diverse artistic inspirations into a unique style. The propylon would be replicated not only in Sharqi monuments but also in buildings at the periphery of the empire, perhaps trying to emulate the wonder of the original structure.

Artistic innovations

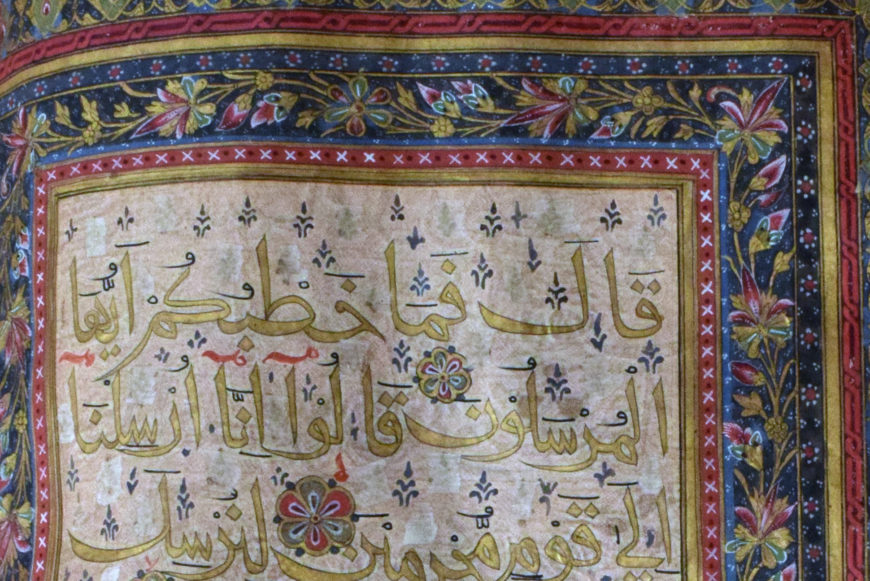

Detail showing the bihari calligraphic style, Bihari Qur’an, 1447, each folio measures 53.3 x 35.5 cm (Photograph courtesy of the National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi – NM.1957.1033)

There were also other artistic innovations in the Jaunpur region. The calligraphic style of bihari is thought to have developed around the region of Bihar in Sharqi-held areas. The script, defined by its thick horizontal strokes and thin verticals, was used primarily in Qur’ans and other religious texts.

A Bihari Qur’an, now in the National Museum of Pakistan, has been associated with the Sharqi sultans of Jaunpur. The Qur’an is a monumental volume of 408 large folios (each folio measures 53.3 x 35.5 cm), its size and opulent decoration both emphasizing its royal patronage. The text is written in gold outlined with black throughout the volume and each section (juz) begins with an ornate decorated double page. As seen here, the text is surrounded by a red checked pattern and set within multiple floral and arabesque borders, which extend out into the wider margin to the right side. No page is the same, with an astonishing variety of designs.

This Qur’an is among a set of highly opulent Bihari Qur’ans, of which the most famous is the Gwalior Qur’an, produced in 1399 in Gwalior, when the city was under the control of the Tonwar Rajputs.

Bengal

The bihari script was widely disseminated across the Indian subcontinent. The earliest surviving example is a Qur’an produced in Lohri (it is unpublished and is at the National Museum in Kabul), possibly referring to the port city of Lahri Bandar in Sindh (Pakistan) and there are numerous examples of architectural inscriptions in bihari from Bengal.

Bengal is located in the eastern part of South Asia and is now divided into the Indian province of West Bengal and the nation of Bangladesh. The region is geographically marked by the Ganges delta, the largest river delta in the world. Surviving written inscriptions from Bengal testify to the presence of highly skilled calligraphers and stone carvers in the region.

Example of tughra script. Dedicatory Inscription from a Mosque, dated A.H. 905/1500, gabbro, made in India, Bengal, 41 x 115.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Tughra script

Apart from bihari, architectural inscriptions in the Bengal were executed in multiple calligraphic styles. One of these styles was tughra, sometimes referred to as “bow and arrow” script, a reference to the evenly spaced rows of thin verticals and pronounced crescent forms of some letters that characterize the script, as seen in this example of a dedicatory inscription for a mosque, now in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Adina mosque

The architecture associated with these inscriptions is also magnificent. The Adina mosque in Pandua was built by Sikandar Shah of the Ilyas Shahi dynasty. A monumental structure, the brick mosque includes a large central courtyard and a prayer hall divided into two wings by a wide central nave. This central nave was originally covered by a pointed barrel vault that spanned a width of 317 feet and rose 565 feet high.

Adina Mosque, commissioned 1373, Pandua, India

In its scale, the form recalls the pre-Islamic monument Taq-i-Kisra in Ctesiphon (Iraq), a symbol of ideal kingship, and also the central aisle of the Umayyad mosque of Damascus, built by the ruler al-Walid. These architectural influences can be connected with how the Sikandar Shah styled himself, calling himself khalifa (successor to the Prophet), a stylization further emphasized by the inscriptions in the mosque where he is described as “the most perfect of the kings of Arabia and Persia” with no mention of Bengal.

Reused stone with Hindu gods, Adina Mosque, commissioned 1373, Pandua, India (photo: Rupu, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The mosque’s artistic referents are extremely wide-ranging, combining indigenous building traditions with imported ones. Although the building is constructed of brick, the prayer hall is faced with dressed stone, some of which is carved, including the central mihrab and a canopied minbar, in combination with terracotta decoration. The stone is reused from existing Hindu or Buddhist temples, with older carving visible in some exposed parts of the structure, such as a kirtimukha (lion “face of glory”) visible through the space where the top step of the minbar used to be.

Hanging lamp motif, central mihrab, Adina Mosque, commissioned 1373, Pandua, India (photo: Amitabha Gupta, CC BY 4.0)

Many of the carved patterns are locally derived, though sometimes they depict widely used Islamic motifs, such as a hanging lamp motif in the mihrab niches, a reference to the same Light verse in the Qur’an noted earlier. The carvings also includes the use of Chinese-style lotus and peony motifs in the carving above the south mihrab the raised royal enclosure, perhaps inspired by Chinese imports to Bengal, including silks and porcelain.

Sindh

The importation of different artistic vocabularies and practices was also notable in Sindh, where the Sammas came to power in the second half of the fourteenth century.

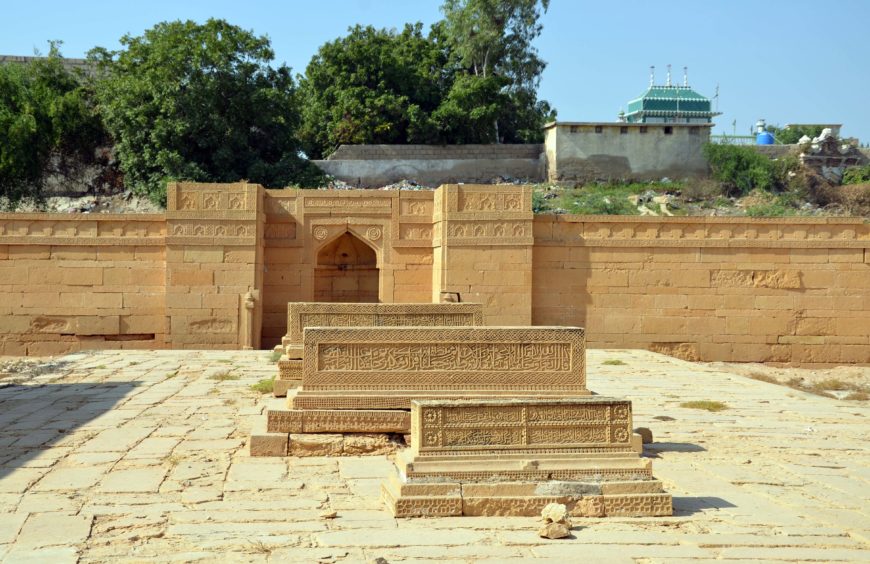

Makli, Samma Cluster (north section of necropolis), late 14th–early 16th century, Thatta, Sindh province, Pakistan (photo: Fatima Quraishi)

Chattri, Makli necropolis, 15th century, Thatta, Sindh province, Pakistan (photo: Gajus, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Little is known about Samma patronage outside of the Makli necropolis (cemetery), located on the outskirts of the medieval city of Thatta. The early architecture of the necropolis was stylistically connected to that of Gujarat and Rajasthan and particularly the Maru-Gurjara tradition discussed earlier. Among these monuments are a group of stone carved chattris (canopied pavilions), all of which follow the same design and decorative scheme and were, therefore, perhaps produced by the same group of artisans. The pavilions are constructed with 6–8 pillars carved with banded decorations and are topped by a corbeled dome that has been plastered on the exterior and with a kalasa (pitcher finial), with concentric rings of stone visible on the interior as well as a padmasila (lotus pendant) in the center. Both the construction methods and the style of ornament are comparable with monuments built in the Maru-Gurjara traditions in Rajasthan and Gujarat.

Makli, brick and tile enclosure, 16th century, Thatta, Sindh province, Pakistan (photo: Fatima Quraishi)

As the socio-political climate of Sindh shifted with the arrival of the Arghun and Tarkhan tribes from Central Asia, so too did Makli’s appearance. Among those relocating to Sindh were probably artisans who introduced underglaze painted tiles in dark blue, turquoise, and white, used as architectural decoration.

Makli, cenotaphs, inside funerary enclosure of Baqi Beg Uzbek, end of the 16th century (photo: Fatima Quraishi)

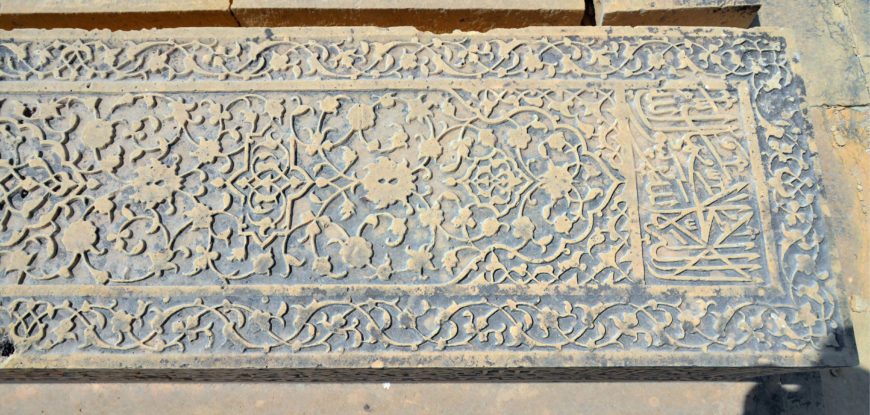

Stone carvers also expanded their repertoire of designs which now included arabesque scrolls and floral vines of lotuses, carnations and peonies. As a result, a number of cenotaphs at Makli closely resemble Timurid gravestones. The decoration of the top face of one cenotaph (shown below) is divided into three parts, an outer border with a vegetal vine, a rectangular panel inscribed with the shahada (proclamation of faith), and a long rectangular central section with multiple decorative motifs.

Central decoration of a cenotaph, Makli necropolis, 1542, for Beg Tarkan, Sindh province, Pakistan (photo: Fatima Quraishi)

The central decoration is framed by a cusped border with multiple cartouches and arabesques. Yet, even as Makli’s architectural style was shifting, there were significant continuities with earlier construction, such as the continued use of chattris (canopied pavilions), demonstrating an active dialogue between local and transregional artistic styles.

Regional traditions

Mobility—of people and objects—played a key role in the development of sultanate art, linking each independent sultanate to a number of different communities. The arrival of new artistic styles and technologies did not happen in a vacuum. Artists and patrons adapted to local conditions and practices. The arts of each sultanate region covered in this essay demonstrate the development of multiple distinct regional traditions.

Notes:

[1] The term Maru-Gurjara was coined by the art historian, M.A. Dhaky, who used it to describe an architectural style that emerged in the eleventh century during the rule of the Solanki dynasty. The style combined the existing sculptural tradition of Rajasthan with the more austere architecture of Gujarat. – M.A. Dhaky, “The Genesis and Development of Maru-Gurjara Temple Architecture.” In Studies in Indian Temple Architecture, edited by Pramod Chandra, 114-165. New Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1975.

[2] This information is based on Elizabeth Lambourn’s “A Collection of Merits,” South Asian Studies 17, no. 1; there is an image of the northwest mihrab in the article (fig. 8).

[3] Maryam Ekhtiar and Julia Cohen, “Tiraz: Inscribed Textiles from the Early Islamic Period,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (July 2015)

[4] Another link between Timurid architecture and Mahmud Gawan’s madrasa is the use of tall corner towers, also notable in Gawhar Shad’s madrasa in Samarqand.

Additional resources

Indian Block-Printed Textiles in Egypt: The Newberry Collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Catherine B. Asher, “Delhi Sultanate Architecture,” in Encyclopaedia of Islam THREE, edited by Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, and Everett Rowson, 2020.

Eloise Brac De La Perriere, “Manuscripts in Bihari Calligraphy: Preliminary Remarks on a Little-Known Corpus,” Muqarnas 33 (2016): pp. 63–90.

Finbarr B. Flood, “Before the Mughals: Material Culture of Sultanate North India,” Muqarnas 36 (2019): pp. 1–39.

Abha Narain Lambah and Alka Patel, eds., The Architecture of the Indian Sultanates (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2006).

Elizabeth Schotten Merklinger, Sultanate architecture of pre-Mughal India, preface (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2005).