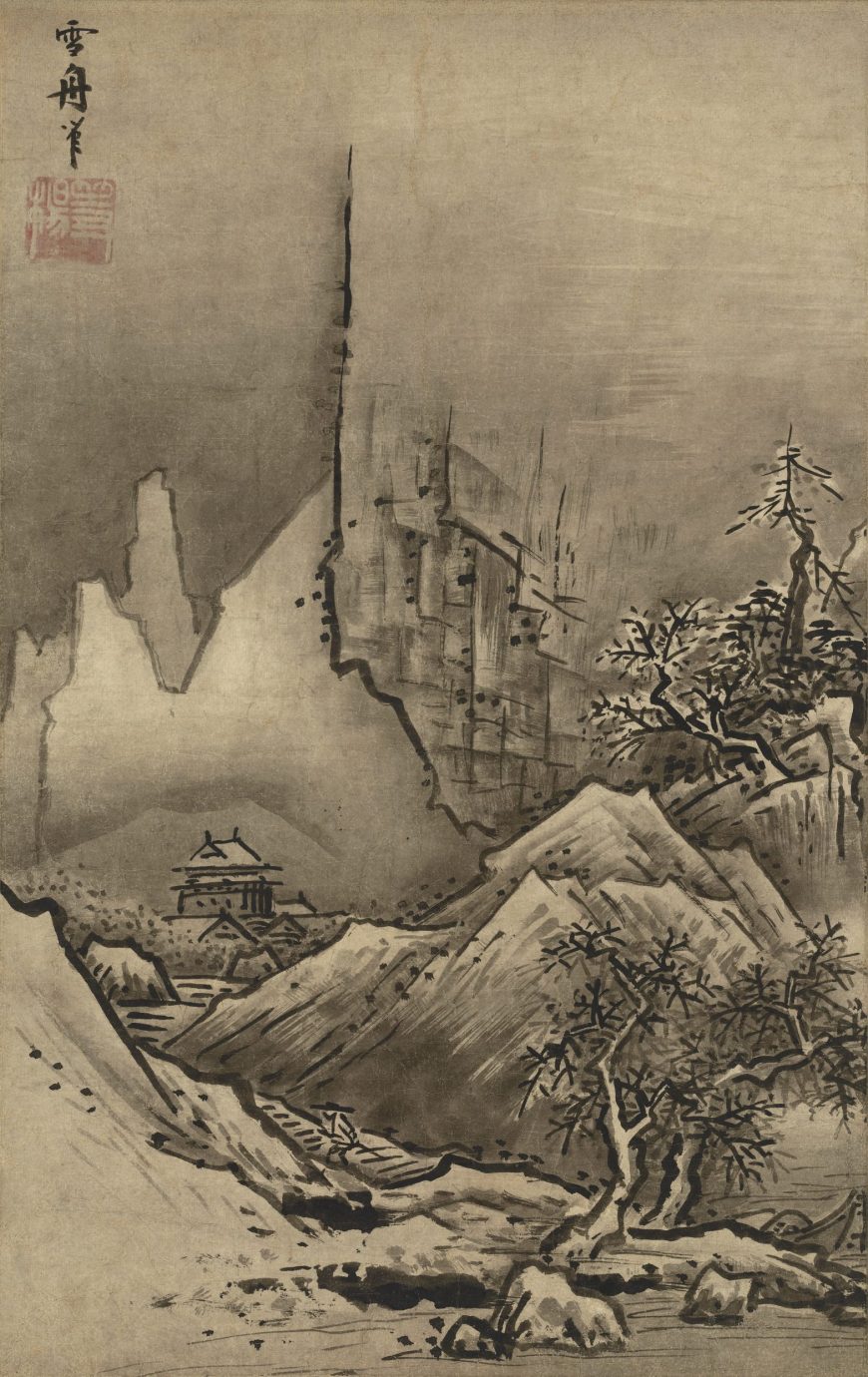

Sesshu Toyo, Winter Landscape, c. 1470, ink on paper, 18 x 11 1/2 inches (Tokyo National Museum, Japan)

Background

A Zen Buddhist monk and Japan’s most influential master of ink painting, Sesshū Tōyō practiced the art of sumi-e – literally, ‘painting in Chinese ink.’ The ink is made by burning pine twigs, collecting the soot, and mixing it with resin. This is made into a flat stick. The stick is then rubbed in a small pool of water in an inkstone. The inkstone has a shallow slope to it, so that the ink can be built up on the slope. By mixing in more or less water, the artist arrives at the desired value.

The rapidity of sumi-e painting—among other aspects— made it popular among practitioners of Zen. Some masterworks of the medium are not slowly and laboriously produced, but rather, rapidly sketched out with quick and fluid brushstrokes.

Artists often aim for economy of strokes — they try to produce their image with as few strokes as possible, striking for the heart of the image rather than fussing about the details of its outward form. Since Zen Buddhists believe that Enlightenment can strike with great suddenness, the form suits the belief.

Visual elements

Sesshū’s Winter Landscape (1470s) is a powerful image. The painter manipulates the visual elements with great care and precision. Since the artist restricted himself to the black sumi ink, the painting is necessarily only in shades of grey. Still, he uses it with fairly high contrast, so that the darkest brushstrokes are very far in value from the smattering of white areas that result from Sesshu’s decision to leave them unpainted.

This high contrast emphasizes the cold, harsh, brittle sense of winter. Most of the contour lines used to define the outlines of the forms — the hills, temple, trees, and the human figure — are heavy and dark. An image of a snowy landscape might be shown as soft and picturesque, with all the edges blurred gently by the muting effect of the falling snow, but that is the perspective we have of the cold while sitting at the fireside. This image, on the other hand, conveys the sense that we are out in the cold. The landscape is of a hard, icy mountain ridge, rather than of soft, snowy woods.

Still, this is hardly a black-and-white image. Instead, Sesshu has made use of a range of values, exploiting the middle grays to build up the weight of winter. The heavy, leaden sky hangs ponderously above. The snow-capped hills turn slushy and dim toward their bases. The only white sections are those around the tree branches, giving the sense that they are covered in snow.

Sesshu Toyo, Winter Landscape, c. 1470, ink on paper, 18 x 11 1/2 inches (Tokyo National Museum, Japan)

Line

The use of line complements the use of contrast in Winter Landscape. The majority of the lines are choppy and jagged. In a depiction of the natural world, we might expect to see more use of organic, curvilinear lines. However, Sesshū constructs the trees, hills, and mountains almost exclusively out of short, straight lines of varying thickness and value. In addition, most of these lines are set at sharp diagonals, with those of the hills almost all at forty- five degrees. This gives the work a sense of energy, though since the lines are set in opposition to one another, with some slanting to the right and others to the left, this energy is pent up, unable to escape in any particular direction.

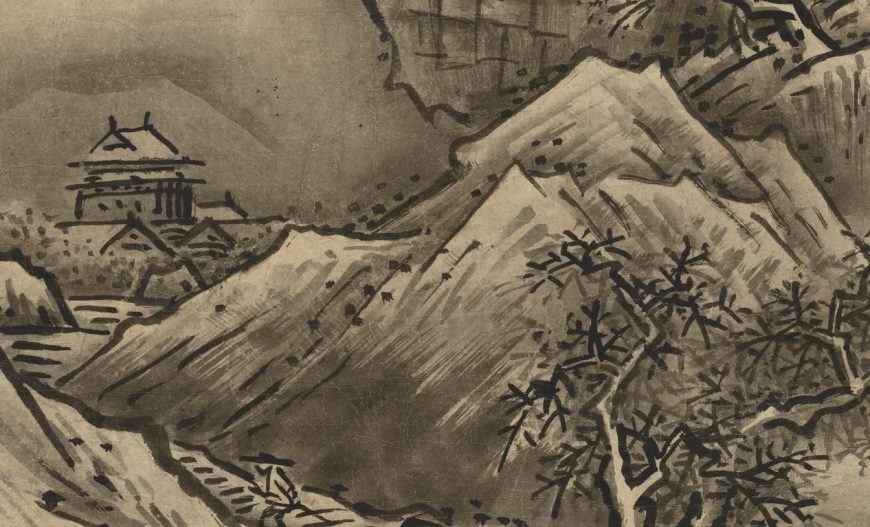

Detail, Sesshu Toyo, Winter Landscape, c. 1470, ink on paper, 18 x 11 1/2 inches (Tokyo National Museum, Japan)

One line, though, dominates the entire composition: the curious heavy, thick, dark line that runs vertically down the image, just left of center. It slashes downward like a bolt of lightning, jogging briefly left and then slanting sharply off to the right. The space to the right of it is filled with a spikey grid composed of short lines that are mostly horizontal and vertical.They intensify the crystalline tone of icy winter. For that matter, what is that dominant line? Is it, perhaps, the edge of an overhanging cliff, threatening the Buddhist monastery crouching beneath it? In that case, the upper portions must be shrouded in mist, since the form simply fades gently away as we move up the painting.

We identify with the small figure who trudges wearily up the long flight of steps, leaning forward into the climb and perhaps into a cold wind, his shoulders hunched up under his broad-brimmed hat. This figure is created through a series of short, quick, straight lines. Sesshu’s economy is impressive – with only a few brushstrokes, he creates not only form but also feeling and mood.

Balance, symmetry and emphasis

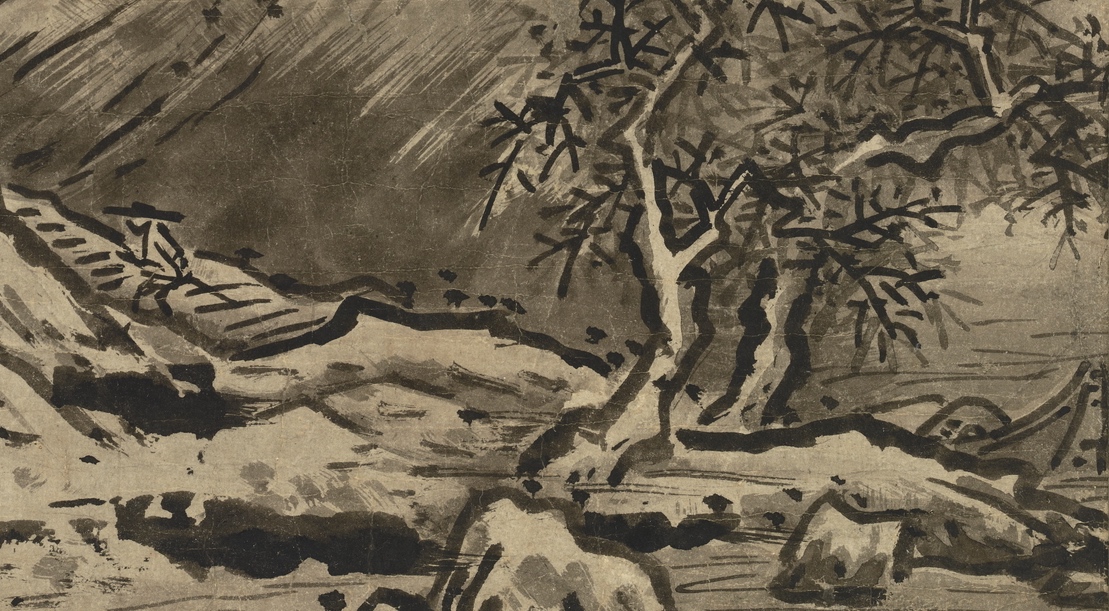

Figure (detail), Sesshu Toyo, Winter Landscape, c. 1470, ink on paper, 18 x 11 1/2 inches (Tokyo National Museum, Japan)

Sesshū’s careful construction of balance is much in keeping with his crisp use of contrast and line. The image is not symmetrical — the two halves do not mirror one another even loosely. However, it has a dynamic, asymmetrical balance. Neither side of the image has greater visual weight to it. Sesshu uses a few techniques to achieve this, foremost among them emphasis.

In this case, emphasis is created through the visual elements discussed above, contrast and line, as well as through the use of concentrated detail. There is more detail on the right side of the painting, particularly in the knotty branches of the bare trees clinging to the rocks. This detail is the result of the sharp, prickly lines that catch our eye, picked out through high contrast with the white around them. On the left, though, the shapes are larger, more open, and brighter. These serve to isolate and thereby emphasize the small series of buildings in their midst. Our eyes therefore bounce back and forth across this image.

The great vertical slash discussed above also works to establish this dynamic balance. It starts almost at the top edge of the image, slightly to the left of center. An artist seeking a more static, symmetrical image might have put it right down the center of the image. However, the line maintains the asymmetrical balance by cutting back to the right and passing through the center of the image.

Figure and boat (detail), Sesshu Toyo, Winter Landscape, c. 1470, ink on paper, 18 x 11 1/2 inches (Tokyo National Museum, Japan)

As we follow it downward, it moves to the right until it runs perpendicularly into the sloping hillside, which in turn carries our eyes down and to the left, and into another series of diagonal lines that move us further down and back to the right, to where the figure has moored his small boat. The line of the large boulders in turn pushes our eye back to toward the left, ending just about in the center of the image. This painting, despite its iciness and balance, is a restless composition.

Cultural context

Zen Buddhism — developed by Bodhidharma (known as Daruma in Japan), a Persian or Indian Buddhist who traveled to China — took root in Japan in the twelfth century. Buddhists seek Enlightenment, which leads to Nirvana, a peaceful escape from a cycle of reincarnation (rebirth) into the world of suffering. Bodhidharma believed that Enlightenment could be achieved through concentrated meditation, rather than the complex rituals practiced by some other Buddhist sects. A crucial element of Zen Buddhism is the belief that Enlightenment can strike a person at any point, and this led to the establishment of practices considered more likely to bring it about, including some that relied on interaction with the natural world.

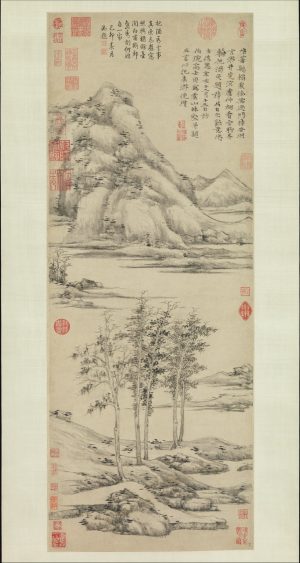

Ni Zan, Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu, 1372, Yuan dynasty, China, ink on paper, 94.6 x 35.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Zen monks were encouraged to wander the countryside, taking solitary journeys to remote landscapes in order to contemplate them. In the words of Dong Qichang, a major painter of the seventeenth century whom many tried to imitate for centuries, “Read ten thousand books, and walk ten thousand miles.” That is, study the works of great masters, and study the works of nature.

Many Zen ink paintings were produced spontaneously or in solitude. An epitaph for the inkmaster Ni Zan (fourteenth century), tells us that “in his late years, he became quieter and more withdrawn than ever. Having lost or given away everything he ever owned, he did his best to forget his worries … He roamed the lakes and mountains, leading a recluse’s life” (epitaph by Zhou Nanlao, fourteenth century).

At the top of Ni Zan’s painting Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu, a poem reads:

We watch the clouds and daub with our brushes We drink wine and write poems.

The joyous feelings of this day

Will linger long after we have parted.[1]

An important concept for Zen-inspired visual artists was wabi — the appreciation of artifice-free beauty in humble and austere circumstances. Wabi has had a strong impact on Japanese culture that continues to this day. It has long been an important aesthetic principle in chanoyu—the Japanese ritual art of preparing and drinking powdered green tea.

Paintings made in Zen contexts were designed to encourage a deeper experience of nature, and to help convey that experience to the viewers. Their purpose is not so much to accurately record the appearance of the landscape, but rather to capture the feeling of a person gazing upon it. Sesshu excelled at this, making works that are not mere representations of the landscape but rather, images that inspire feelings as much by the way the scene is painted as by the content of that scene.

Buddhism

Here again, the basic tenets of Buddhism help us understand the painting further. Buddhism was founded by Siddhartha Gautama (c. 566-480 B.C.E.), an Indian prince who renounced his decadent lifestyle in favor of a life of meditation and simplicity. Gautama was sequestered in his royal palace, rarely venturing outside. On one excursion, though, he encountered the “Four Sights”: an old man, a sick man, a corpse and an ascetic — a person who intentionally lives a simple or even harsh life, usually to achieve spiritual goals. This led him to formulate the Four Noble Truths: Life is suffering; suffering is caused by desire of worldly things and goals; desire can be eliminated; and the Noble Eightfold Path is the route to ending desire and thereby ending suffering. The Noble Eightfold Path, in turn, is: Right Understanding, Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration. This path is designed to guide the Buddhist toward moral conduct, meditation, wisdom, and, ultimately, Enlightenment.

In Sesshu’s Winter Landscape, we can see these principles reflected. Sesshu’s masterful use of visual elements can be interpreted to suggest the message that Buddhism is the path to escape from the suffering represented by the world. While the image seems at first glance to be about the natural world, in fact nature may be used as a metaphor for all elements of our world, natural and human.