The prehistoric paintings found at Chauvet Cave are remarkable works that suggest that humans have imagined concepts of the supernatural from our earliest moments.

We cannot know the specifics of the beliefs and rituals that occurred there, since its creator(s) left no writings, but we can hypothesize about them. We can be fairly certain, whatever they intended as they crawled through narrow openings, dragging their supplies with them into stifling, pitch-black caverns lit only by their smoldering lamps, that the images these prehistoric people produced were not for mere decoration, entertainment, or idle fun.

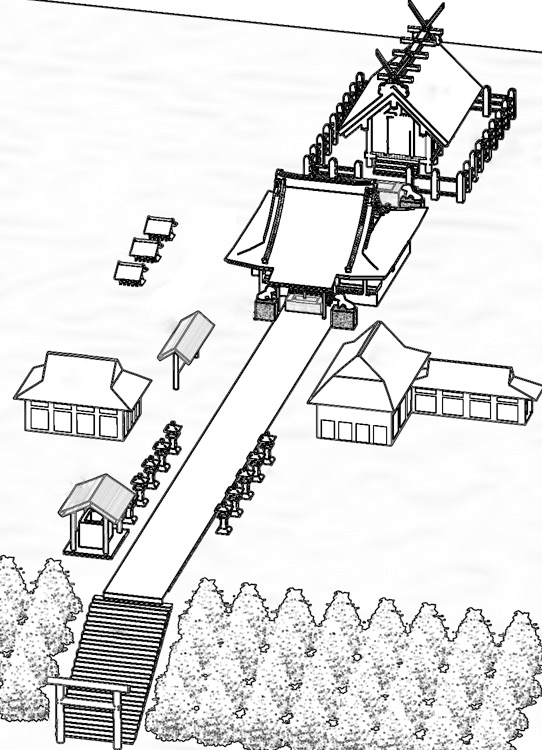

Shinto Shrine, Ise, Japan

If the cave paintings might suggest some form of nature worship, then they are evidence of a first in a long line of such beliefs from throughout world history. In Japan, the Shinto religion is focused on kami, deities that can inhabit aspects of nature like trees, rocks, waterfalls, and animals, which then become sites of worship.

Kōtai-jingū (Naiku) at Ise, Mie prefecture, Japan (photo: N. Yotarou, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Originally, Shinto was not a codified religion, though it later became more firmly based on rituals. The Shinto Shrine at Ise, officially known as the Ise Jingu, one of the most famous religious sites in Japan and Shinto’s central one, embodies, in its design, many aspects of this religion’s intimate connection to nature. It is built entirely of natural materials, with walls and beams made of Japanese cypress and a thatched roof made of reed and short, rounded logs. Scholars believe that it was originally built in the first century C.E., and then rebuilt in a time of cultural change in the seventh century. Since then, craftsmen who train for a lifetime rebuild it every twenty years. Their work of periodically rebuilding it is an act of devotion that reaffirms spiritual and cultural bonds. The techniques and materials are consciously old-fashioned, but the resulting shrine appears fresh, if only because of the visibly new materials used in its construction. It was last rebuilt in 2013, and will be rebuilt again in 2033. This might be seen as a reflection of the core Shinto practice of ritual purification as a form of renewal.

The shape of the shrine is based on raised granaries used for food storage, which became standard for Shinto shrines. The shrine at Ise is dedicated to Amaterasu-o-mi-kami, the sun goddess and mythical ancestor of Japan’s imperial family. Since its establishment, the Ise shrine complex has housed several sacred objects, including a mirror associated with Amaterasu, and a symbol of wisdom and truth. These same values are emphasized by the consciously simple materials of the shrine. Still, with over 125 shrine structures in a complex that is home to over 1,500 yearly rituals, Jingu is nothing short of impressive.

Like most high-status religious structures, the main shrine is symmetrical, which makes it seem stable and dignified. It is set at the end of a long path, behind a series of gates that provide a sense of entering into a sacred space for those permitted within.

Great Stupa, Madhya Pradesh, Sanchi, India

A similar technique is used at the Great Stupa at Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh, India. An earlier brick-faced stupa constructed in the third century B.C.E. by the emperor Ashoka was expanded to twice its size and faced with sandstone in the first century C.E. with donations from pious individuals. It is again removed from daily life; in this case, the whole monastic complex is located only a short distance from the city, but through its design, the sacred center is set off from worldly activities.

Yakshi, Great Stupa, Sanchi (photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, CC BY 2.0)

Surrounding the dome-shaped mound of the main stupa is a large stone fence with four thirty-five-foot-tall stone gateways, or toranas, located at the cardinal directions (North, South, East, and West). These gateways are open, so they do not function like those guarding the entry to Jingu. Instead, they function to help pilgrims — people who travel to holy sites for religious reasons — transition from the ordinary world outside the gates to the sacred space within. Indeed, the Buddha is said to have requested to be buried at a crossroads, so that it would be easier for travelers to visit the site.

Unlike Chauvet Cave, the intent here was for the imagery to be as clearly visible to as many people as possible. The toranas are the only part of the Great Stupa to have sculpture. They were directly aimed at pilgrims, who would first walk around the exterior, looking at the images, and then again would enter through a torana and circle the stupa itself, looking at the imagery on the toranas. Buddhists believe in reincarnation — the notion that we are reborn into new bodies when we die — and many of the carvings show scenes from the Buddha’s past lives, as well as real and mythical animals, and other beings. Perhaps the most compelling of these are the yakshis and yakshas, benevolent female and male minor deities common in Indian belief and found in both Buddhist and Hindu art.

One such yakshi hangs lightly from a branch. Her sensuous body nimbly sways and her legs gracefully cross at the shins. She has full breasts and her genitals are revealed through the diaphanous skirt she wears, so sheer that it is only visible because of its hem that cuts across her anklets. These attributes convey a sense of fertility and in turn prosperity, following the pan-Indian belief that depictions of women in sacred art signals auspiciousness. She is a personification of nature, and therefore of life. At her touch, the tree above seems to explode with its bounty of fruit, working like the images at Chauvet to remind the viewer of natural cycles of fertility.

While the toranas are covered in compelling images, there are no images of the Buddha himself. He is instead shown through his absence, though images of his footprints, empty thrones, and the like. In strong contrast, in Ancient Greece images of the gods were seen as necessary for worship.

Zeus, Ancient Greece

The religion of the ancient Greeks was polytheistic (they worshiped many gods). Worship was conducted through sacrifice to the gods, but in order for the sacrifice to be meaningful, a god had to be present. Sculptors were therefore commissioned to create impressive images of the gods that served as idols (images to be inhabited by gods).

Works like the impressive bronze Zeus, c. 460-450 B.C.E., were not merely decorative or instructive, not designed just to give viewers an idea of what the god looked like or to teach worshippers about him. Instead, they were designed to entice the god, or at least some portion of his or her divinity, to enter the statue, which would then serve as an object of devotion and sacrifice, as may have been the case at Chauvet Cave.

Artemision Zeus, c. 460 B.C.E., bronze, 2.09 m high, Early Classical (Severe Style), recovered from a shipwreck off Cape Artemision, Greece in 1928 (National Archaeological Museum, Athens)

Artemision Zeus, c. 460 B.C.E., bronze, 2.09 m high, Early Classical (National Archaeological Museum, Athens)

The figure is majestic. While the body is naturalistic, it is also highly idealized, with firm muscles that seem at odds with the age of the long-bearded figure. He once held a thunderbolt in his raised right hand, indicating that this figure is Zeus, the supreme deity of the Greeks and ruler of the sky.

The figure does not have any inscriptions on it, and yet we can be sure it is a god because of the manner of his depiction. The figure’s intent is clear: He is about to hurl a weapon, probably to destroy a mortal person, and yet his face is utterly aloof. It is rigidly symmetrical, implying the god’s perfection, with even his hair falling in paired locks from the center, outward along his forehead. The god’s expression is fixed, as he looks down on his victim without a trace of mercy.

Christ as the Good Shepherd

Early Christians, living in a Greco-Roman world where this sort of imagery was the standard, sought an image of their new god that would be greatly at odds with the often-merciless polytheistic pantheon.

An early relief sculpture of Jesus Christ as the Good Shepherd, from the third century C.E., is typical of this period. Here, instead of older, powerful, domineering gods like Zeus and Poseidon, Jesus is shown as youthful, soft, and gentle in appearance.

His body is still naturalistic and idealized, in that it seems young and healthy, but in place of the muscular nude of the Greek god, he is modestly clothed in the robes of a simple shepherd. Jesus carries a lamb on his shoulders, in reference to a series of passages from the Bible, including Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not be in want…”) and Jesus’ Parable of the Lost Sheep:

“Suppose one of you has a hundred sheep and loses one of them. Does he not leave the ninety-nine in the open country and go after the lost sheep until he finds it? And when he finds it, he joyfully puts it on his shoulders and goes home. Then he calls his friends and neighbors together and says, ‘Rejoice with me; I have found my lost sheep.’ I tell you that in the same way there will be more rejoicing in heaven over one sinner who repents than over ninety-nine righteous persons who do not need to repent” Luke 15: 4-7

In essence, the message conveyed is that the viewer is the lost sheep, and that Jesus—unlike the Greco-Roman deities—cares about each person as the shepherd cares for his flock. At Chavuet, we were presented with a great number of animals, but it is not clear that we are intended to identify with them. Here, though, the animal is a stand-in for the viewer, saved by a merciful god. The Greek god stared down at his human victim coolly, without emotion; here, the sheep look at Jesus. The message of such an image was clear and persuasive to many: This was a god that cared about his followers.

The Last Judgment

Last Judgment Tympanum, Central Portal, West Facade, Cathédrale St-Lazare, Autun, France, c. 1120-35

About eight centuries later, when the a depiction of the Last Judgment was carved over the West entrance to the Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun, France, c. 1130, Christianity had become the most common religion in Europe. Christian art was therefore no longer primarily focused on winning new converts. With new goals come new styles. On the right side of this tympanum — the semicircular sculptural panel over the doorway — we see the Archangel Michael weighing souls to determine whether the souls of the dead will rise to the joys of heaven or descend to the torments of hell. Emphasis is no longer on Jesus as the savior of lost sheep and protector of his flock. Instead, Jesus is now an expressionless judge, showing no greater visible compassion to those on his left (the damned), being pulled and pushed into the mouths of hell, than the Greek god showed to his victim.

The image of Jesus is no longer naturalistic. Instead, it is highly abstracted, elongated dramatically and flattened out. Unlike the robust, active Greek god, he seems almost passive, elevated in a mandorla (the full-body halo that surrounds him) but also contained by it.

Last Judgment Tympanum, Central Portal, West Facade, Cathédrale St-Lazare, Autun, France, c. 1120-35, church 1120-46 (consecrated in 1130)

The composition relies on hieratic scale, with the importance of Jesus conveyed by his enormous size; angels and saints (Christian holy figures) are half his size, and ordinary people below their feet in the lintel running across the bottom of the image, are shown as tiny, fragile figures, cringing and cowering as they approach the moment of their judgment.

Souls being coerced into Hell, Last Judgment Tympanum, Central Portal, West Facade, Cathédrale St-Lazare, Autun, France, c. 1120-35

The whole composition is roughly symmetrical, with elements arranged on either side of the central figure of Jesus. Components on each side balance those on the other without exactly mirroring them. Architectural elements like arches and columns divide the image into sections. The effect is of an elaborate cosmography — an understanding of the organization of the universe — of heaven and hell, the blessed and the damned, centered explicitly and absolutely on the massive figure of Jesus at the center.

Unlike Chauvet Cave, where there was no clear principle of organization dominating the full image and no clear relation between the animal figures throughout it, here, everything is ordered and precise; all relationships between figures are clearly defined. This visual difference likely reflects substantial differences in the religions of their creators. On the other hand, the Last Judgment tympanum at Autun can be connected to Chauvet Cave in that it, like the toranas of Sanchi and the gates of Jingu, marks the entrance to the sacred space, and within that cavernous space, ritual and belief join to create the religious experience.

The North Portal of the Cathedral of Saint-Lazare, Autun has been damaged and rebuilt, but sculptures from the original design survive, including a sinuous image of The Temptation of Eve. At this point in the story, the monotheistic god Yahweh (shared by Judaism, Christianity and Islam), has created Adam and Eve. He then put them in the Garden of Eden, a place of ease and innocence with only one rule, recounted in Genesis 2:17: “You must not eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, for when you eat of it you will surely die.”

The Temptation of Eve, Cathédrale St-Lazare, Autun, France, c. 1120-35 (Le musée Rolin, photo: Holly Hayes, CC BY-NC 2.0)

We find Eve as she picks the fruit in an oddly distracted manner. She has a dreamy expression on her face, and reaches casually behind her to pull the fruit from the tree. Only a close look reveals the clear danger of this act: at the right edge of the image, where the branch of the tree of knowledge bends sharply toward Eve, is the claw-like hand of the devil. The rest of the figure is now lost, but this sharp-taloned remnant, grasping the branch and bending it toward the distracted figure of Eve, serves to suggest the import of the otherwise peaceful scene.

She is completely without clothes, but unlike the artist of the Yakshi discussed above, the artists here relied on a strategically placed plant to cover her groin. This is an image about the dangers of sexual temptation, rather than about the wonders of fertility and bounty. The strong horizontality of the image emphasizes her lowliness. Her body snakes through the underbrush and she is surrounded by twisting, serpentine plants. Even a lock of her hair zigzags along her arm. Indeed, all of the lines in this image twist and turn, so that the viewer connects Eve with the Serpent, the form of the devil in this part of the biblical narrative. The visual association of the serpent and the plants fosters a suspicion of the natural world as dangerous, rather than beneficial.

Yam Mask,early to mid-20th century, Abelam people, fiber and paint, 25 inches (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Abelam society

Religion and the natural world intersect not only in the teeming images of Chauvet Cave and the serpentine sculpture at Autun, but also in art produced in the lush foothills of northern New Guinea. This is the home of the Abelam, a group for whom male status rests on participation in the Tambaran (“Men’s House”) cults. These cults are central to Abelam society, and have a strong influence on their art and architecture.

The giant, human-sized yams at the heart of the cult — not the variety they grow for food — are sometimes themselves considered works of art, and are associated with ancestors, as well as with the potency of their growers. During the annual harvest festival, the spirits of ancestors are believed to inhabit the yams. Their presence is reinforced by placing yam masks atop the yams, which are also dressed in full regalia — ceremonial clothing and objects.

These masks are only loosely anthropomorphic (that is, having human qualities) with highly abstracted features. On this particular mask, as is frequently the case, the eyes are highly emphasized, so that the ancestor seems to be present and watchful. The yams also wear elaborate headdresses, like those worn by Abelam men, to indicate their status. The images, then, like the images of Chauvet Cave, suggest fertility and abundance, as well as ancestry.

The growing of these remarkable yams is, for the Abelam, a secret activity undertaken by the members of the yam cult, composed of initiated men and centered on the Korambo or Ceremonial House, used to store and hide the images until the annual festival. The massive structure, the size of which denotes its importance, is covered with extensive images of ancestors. These faces are, like the yam masks, abstracted images with large, staring eyes. They are nearly identical, establishing a strong pattern that emphasizes the unity of the group.

What matters here is not some sort of naturalistic representation but rather the power of the image. While the interior images are not as precisely patterned as those on the exterior, they nonetheless hold together to produce a cumulative effect. They so thoroughly cover the interior that, when the members of the yam cult view these images alongside freestanding carved ancestor images, the yam masks, and the yams, themselves, the members would seem to be surrounded on all sides by their revered ancestors. The environment is, like that at Chauvet, completely immersive.

Additional resources:

Art and religion from The National Gallery, London