Art is designed for a great many purposes, but much art is also, if not exclusively, designed to provide and reflect a sense of pleasure. A palace might be intended to display the power and wealth of a ruler, but also to provide that ruler with a pleasurable home. A soaring and glorious Christian church may serve as a tool to help a worshipper understand what heaven might look like, but the method to achieve this entails inviting aesthetic pleasure.

Gardens and pleasure

Here, we will consider and compare several gardens, which are spaces designed to provide pleasing, immersive environments. While not always included in discussions of art, gardens can be considered a form of architecture and are precisely planned to heighten the pleasure of those resting in the shade of their trees.

Wealthy patrons, like kings and emperors, often commissioned prominent artists and architects to design their gardens. Contemplative monks worked on their own gardens as part of their worship. Governments and civic organizations design gardens today to mark and celebrate their presence or simply for the public to enjoy. All the gardens presented here constitute microcosms of a desirable world—whether real or imagined.

Gardens and garden paintings across cultures

Many cultures around the world created gardens as spaces of pleasure. Indeed, the modern English word “paradise” is based on an ancient word for “garden.” Each culture designs its gardens in its own fashion, reflecting different notions of beauty and different concepts of pleasure.

We will continue our exploration of gardens as pleasant microcosms by taking a closer look at noteworthy gardens in medieval Japan, twentieth-century England, seventeenth-century France, representations of early Mughal Empire gardens, and finally Monet’s gardens at Giverny. We will then consider images of gardens, designed to reflect the pleasure actual gardens inspire. Just as many choices need to be made in the layout of a garden as in the design of any complex work of art or architecture—and each one reflects the values and goals of its designer.

Ryōanji (Peaceful Dragon Temple), Kyoto, Japan, dry rock garden (image: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA)

Japan: Simple yet dramatic monastic gardens

In Japan, the kare sansui 枯山水—the dry garden—was fully developed in the Muromachi period (1333–1568). Elements of the dry garden can be found in Japanese culture dating back over a thousand years earlier, but it was in the Muromachi period that the form came into its own. Kare sansui can be literally translated as “withered mountain-water.” These gardens, influenced by Zen Buddhism imported from China, are “gardens” only in a loose sense, as some contain little or no greenery.

The most famous dry garden is at Ryōanji, the “Temple of the Peaceful Dragon,” in northwest Kyoto. The current garden was established in 1488 by Hosokawa Masamoto, a powerful clan leader, after an earlier temple on the site burned down.

Rock garden, Ryōanji, Kyoto, Japan (photo: Mr Hicks46, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The design is startlingly simple. Like the Chinese scholar’s gardens, there is a focus on dramatic rocks, but just about every other element has been removed. The result is stark and open, with far more negative space than positive: the garden, enclosed by a rectangle of walls and with a viewing platform along two sides, consists of fifteen rocks, arranged into three clusters. These rocks, like those chosen for the Garden of the Humble Administrator, are individualized, craggy, irregular masses of stone.

It seems that originally visitors were able to walk through the garden, treading on the gravel around the rocks, though now they are restricted to the platform.

Ryōanji (Peaceful Dragon Temple), Kyoto, Japan, dry rock garden (image: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA)

The rocks float like islands in a sea of gravel. Like the elements of a Chinese scholar’s garden, the rocks are not arranged with symmetry but still possess a very careful balance between close and far, large and small, and few and many.

The Ryōanji rocks have been assigned various symbolic readings—e.g. they are a constellation of stars, the islands of the ocean, and even a group of tiger cubs swimming—but the effective simplicity of the garden seems to go beyond any such readings. The moss clinging to the rocks’ bases is the only plant life in the garden. The dominant element, here, is open space, which is appropriate for a Zen Buddhist context.

The garden was designed to provide a site for contemplation, in the hope that the viewer might, through such contemplation, achieve enlightenment. While the garden at Ryōanji is not lush or lavish, its quiet, gentle balance provides a peaceful environment in which the Buddhist devotee can strive toward freedom from suffering.

England: the bountiful chaos of the country garden

A memorial plaque for Gertrude Jekyll in a garden she designed at Lindisfarne (image: M J Richardson CC BY-SA 2.0)

Traveling to England, we find a rather different approach. The typical aesthetic of the English country garden is bountiful chaos. At Munstead Wood, the home of Gertrude Jekyll, “the grand old lady of English gardening” [3] we see great heaps of wildflowers, not quite wild but not arranged in any rigid way, either. Jekyll is considered to be the strongest influence on the development of the English country garden. She grew up in the small, picturesque village of Bramley, with aspirations to be a painter, and she practiced a remarkable array of arts, from metalwork and carpentry to embroidery and wallpaper design, before ultimately focusing her efforts on gardens.

All her earlier explorations of the arts were part of her development as a gardener, and she considered her gardens to be works of visual art, writing to an artist friend that she was “doing some rigorous landscape gardening … doing living pictures with land and trees and flowers.” [4] Remarkably, some autochromes—early color photographs—survive from around 1912, providing us with a sense not only of the design and layout of her garden, but also her rich use of colors that made her famous.

Rather than organizing her gardens into neat bands of carefully trimmed and manicured plants, Jekyll cultivated a carefully controlled chaos, a riot of wildflowers loosely grouped into bands and borders by color and height. The overall effect seems, at first glance—like that of the Garden of the Humble Administrator and Ryōanji—to be casually arranged, tossed together, but as with each of these gardens, the effect was the result of great care.

The garden at Munstead Wood, photographed c. 1912, detail. Originally thought to have been taken by Gertrude Jeykll, but later attributed to Herbery Cowley, then Country Life Gardens editor (image: © Country Life Picture Library)

Indeed, Jekyll completed the plan for her garden before she even began to plan the house around which it was arranged. The garden and the eventual home at its center were carefully integrated, such that the house provided pleasing views of the garden, and the garden provided pleasing views of the house. As Jekyll wrote, “My own little new-built house is so restful, so satisfying [and] so kindly sympathetic.” [5] The overall goal, then, was to provide the occupant and her guests with comfort and pleasure at every turn.

The meandering rill at Rousham house and gardens, designed by Charles Bridgeman and updated by William Kent in the 1730s, Oxfordshire, England (image: Financial Times)

Jekyll’s garden style grew from the tradition of the English garden, which emerged in the early 18th century as a foil to the rigidly symmetrical gardens of France. The English garden was invented by two 18th-century landscape designers, William Kent and Charles Bridgeman. Kent was also a painter, architect, and furniture designer, while Bridgeman was also a horticulturalist. Like Kent and Bridgeman, Jekyll, too, a century later, drew on her multifaceted expertise in the arts to envision and develop her deliberately “natural” gardens.

France: symmetrical gardens as symbols of political power

In contrast, the gardens of eighteenth-century France are certainly among the most rigid yet powerful. At the massive Palace of Versailles, the garden became another expression of the might of the king. Its plan encapsulates its principles of design.

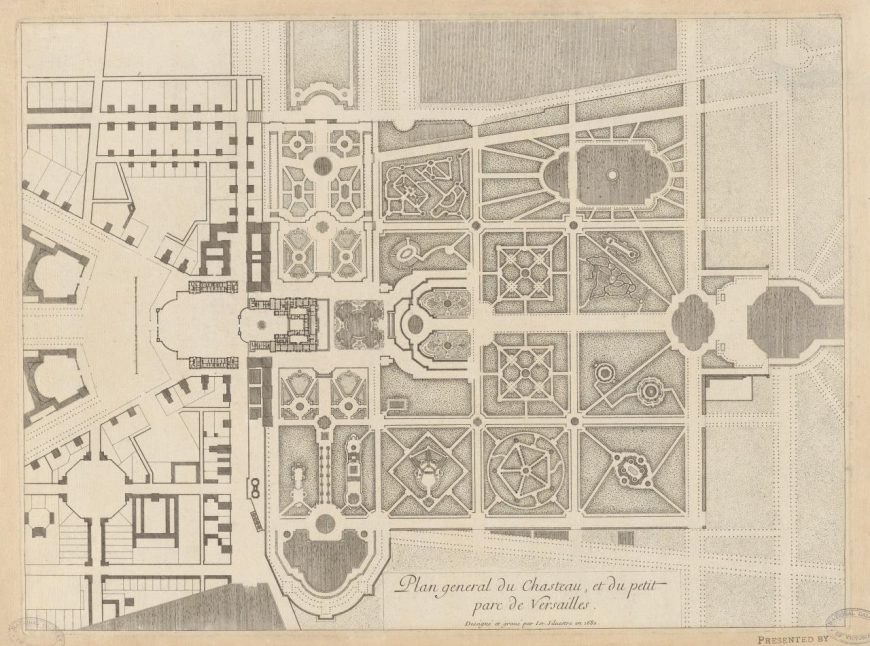

Israël Silvestre, Plan General du Chasteau, et du Petit Parc de Versailles, 1680 (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne)

Unlike the Chinese scholar’s garden, the Japanese Zen Buddhist garden, and the English country garden, the French royal garden is both axial and symmetrical. Indeed, the plan contains a series of symmetrical arrangements of symmetrical elements. The main section of the gardens behind the palace, for example, consists of a nearly square grid of squares, each of which in turn is divided by paths and hedges and planting beds into complex symmetrical designs. These squares are all arrayed around the large path that defines the central access and leads to the large reflecting pool.

Latona parterre (fountain and lawn), designed by André Le Nôtre, 1660s, Versailles (image: Palace of Versailles)

While, unlike the garden at Ryoan-ji, plant life is everywhere we turn, nature itself seems to have been brought under the absolute control of the king. In the English garden, like the Chinese scholar’s garden, the design gives the impression that nature has simply been allowed to run its course—though this is a carefully constructed illusion. At Versailles, not only are the plants laid out in geometric patterns. The plants themselves are not permitted to take their natural, irregular shapes, but are instead shaped into geometrical forms—cones, rectangles, and spheres. The overall effect is pleasurable— stunning and impressive—but also formal and stiff.

The gardens were commissioned in 1661 by Louis XIV, known as the Sun King, a so-called absolute monarch—that is, a king with total power within his kingdom. His palace and gardens at Versailles were an expression and extension of his power. The gardens took decades to complete, through the collaboration of several designers, including André Le Nôtre, who was their primary designer, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Superintendent of the King’s Buildings, Charles Le Brun, First Painter of the King, and Jules Hardouin-Mansart, an architect. The king himself was also highly involved in the creation of the gardens, keeping an eye on all aspects of their design. In addition, an army of men—or at least, regiments of the French army—was employed to bring in plants from all over France.

Garden-facing windows parallel mirrors in the Galerie des glaces (Hall of Mirrors), Palace of Versailles (image: Wikimedia Commons, Myrabella CC BY-SA 3.0)

The king considered his gardens not only as important as the palace, but as an important part of the palace. Interior and exterior spaces were connected by large windows, and also by carefully designed plays of light and shadow. The large reflecting pools, for example, are aligned to reflect the sun up and into the Grande Galerie, or Hall of Mirrors, where it would be reflected and refracted in the 357 mirrors that line the wall opposite the row of windows overlooking the gardens. The sunlight, sparkling on the surfaces of the pools and fountains, and twinkling along the Hall’s mirrors, would embody the power of Louis the Sun King. They would also provide pleasure for the king and his court. Indeed, the two are tied together. The ability of the king to command the creation of such a sublimely pleasurable space was a demonstration of his absolute power.

Representing spaces of pleasure

We have so far considered actual spaces of pleasure. Now we will turn to representations of such spaces, starting with John Vanderlyn’s Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versailles.

Vanderlyn’s panoramic view of Versailles: an immersive environment

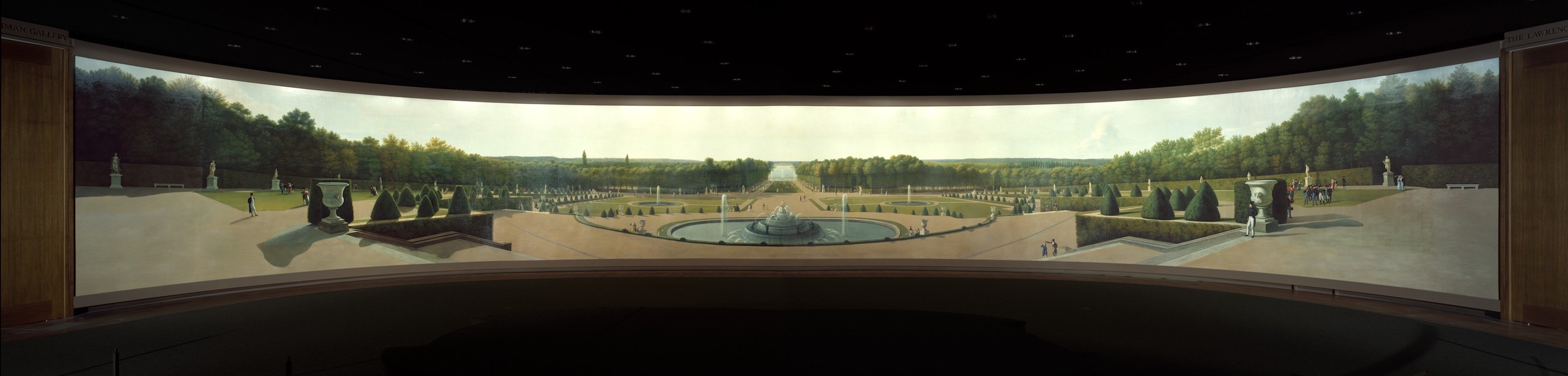

John Vanderlyn, Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versailles, 1818–19, oil on canvas, 12 x 165 ft. (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

This giant painting is one of only a few to have survived from an American fad for panoramas in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries. The panorama bends into a circle 12 feet tall and 165 feet long and was originally displayed in a round building. Now housed in a round gallery in The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, it remains an immersive environment. Such panoramas provided a sort of virtual travel in a period when only the very wealthy might travel from the U.S. to France. For a small fee, visitors could enter the darkened room containing the Panoramic View of the Palace and Gardens of Versailles and imagine that they were at the grand palace of king Louis XIV. When viewed as if a flat painting, the image is stretched and distorted, but when viewed in a 360° space, the illusion is startlingly good.

Vanderlyn’s Panorama in the Lawrence A. and Barbara Fleischman Gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The horizon line is set to roughly the eye level of an expected viewer, which means that when we look out toward the horizon, we seem to be standing naturally in the landscape. As we focus on any detail of the image, we see out of the corners of our eyes more and more of the scene. The effect was, in essence, the nineteenth-century equivalent of our Imax screens—the largest, grandest and most impressive false image available. It was a spectacle designed to make visitors gape and gasp with pleasure.

The layout of the landscape painting emphasizes the formal layout of the garden, especially its geometrical, symmetrical organization. By placing the viewer precisely at the center of the main axis, aligning the viewer’s eyes with the pinnacle of the fountain, Vanderlyn calls attention to the careful design of the gardens, but also elevates the visitor. By placing his virtual tourists—not able to travel to Versailles but able to afford admission to the panorama—at the center of the gardens, Vanderlyn allows the viewer to momentarily feel not merely like a tourist, but to enjoy the pleasure of the fleeting fantasy of being the French king himself.

Detail of Vanderlyn’s Panorama in the Lawrence A. and Barbara Fleischman Gallery, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The centerpiece of the image features a vast vista, punctuated with water. First, we see a giant fountain, cascading downward like the tiers of a wedding cake. Then, there is an open gravel path, a grassy sward, another fountain, a reflecting pool so large as to appear to be a lake, and beyond, more grass and trees. Turning to the left or right, we can see the steps that lead downward, inviting us to imagine walking down to the next plateau, joining the well-dressed couples populating the scene — men with cravats and women with parasols — and onward, out toward the horizon.

The Mughal-empire Baburnama: reconstructed gardens and lineages of power

The Baburnama—the personal memoirs of Babur, founder of the Mughal Empire (who ruled 1526-30 C.E.)—recounts the process of laying out the Bagh-i-Wafa (Garden of Fidelity), the first garden that Babur commissioned. This painted manuscript was created for Babur’s grandson, Emperor Akbar (ruled 1556 – 1605 C.E.).

Babur was very interested in gardens, which in the Indo-Persian tradition were carefully designed with both spiritual and aesthetic intent, and he focused his artistic patronage on their creation.

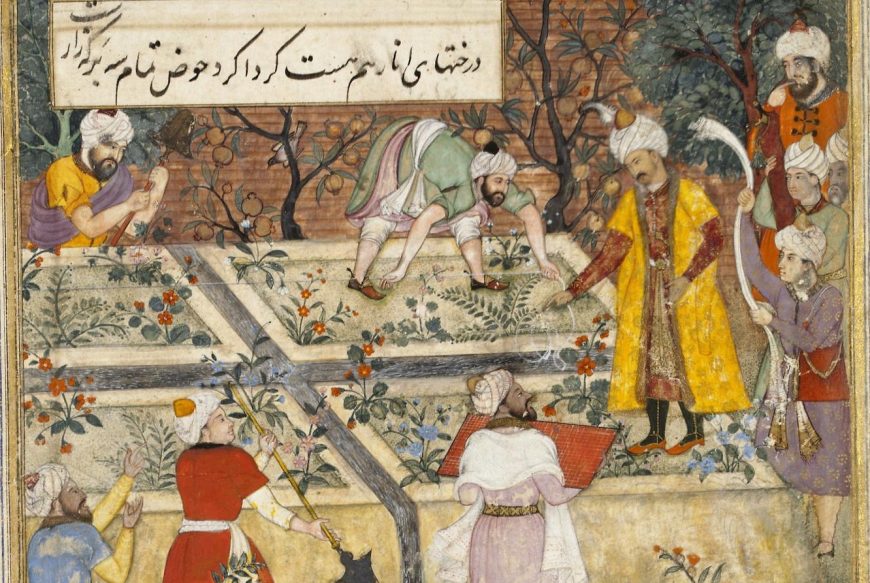

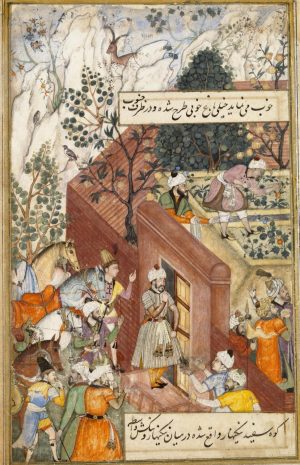

Detail, Bishndas and Nanha, Babur supervising the laying out of the Garden of Fidelity, c. 1590, Mughal Empire, opaque watercolour on paper, 21.7 cm high (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

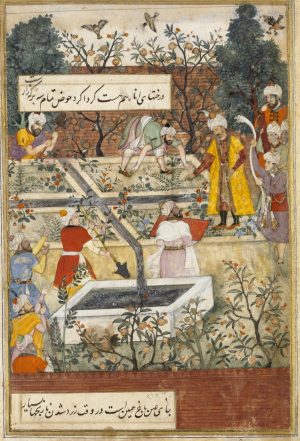

Bishndas and Nanha, Babur supervising the laying out of the Garden of Fidelity, c. 1590, Mughal Empire, watercolor on paper, 21.7 cm high (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

Babur was particularly fond of the chār-bāgh—a garden divided into four by water channels. After conquering Kabul (in modern-day Afghanistan), he built numerous gardens there, as well as throughout his territory, which included northern India. These gardens were not only pleasurable; they were built to house pleasurable activities, including parties, dinners, and poetry readings.

In the image of the laying out of the Kabul garden (above), we see Babur at the far right, clothed in flowing yellow robes and a white turban, overseeing the planting. In front of him, just behind a water basin, the architect holds up the grid plan for the garden.

This suggests the highly organized and rational nature of the garden, echoed in the raised planting beds before him. The architect turns to look at Babur, who in turn looks down toward the plantings at his feet.

Bishndas and Nanha, Babur arrives to supervise the laying out of the Garden of Fidelity, c. 1590, Mughal Empire, watercolor and gold on paper, 22.2 cm high (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

In another image (see left), we see the outside of the walls of the garden, where the natural landscape provides a strong contrast.

In the upper left are a series of craggy mountains, inhabited by animals. Scraggly trees rise out of the barren rock, whereas within the garden, trees hang heavy with yellow fruits that echo the robes of Babur, suggesting that his wealth and bounty is the source of the garden’s fertility.

Babur wrote critically of the disordered landscape of the region, and his formal gardens may have been a response to this perceived chaos. In place of asymmetry and organic shapes, his garden is depicted as a symmetrical arrangement of rectangular planting beds.

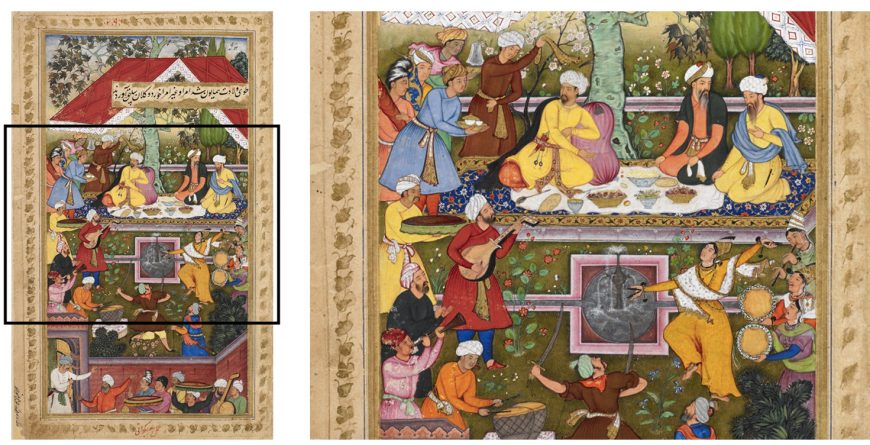

In another image of Babur, we see the great founding emperor in one of his gardens. Babur reclines beneath a tree, seated on an ornate carpet laid with dishes. He is fanned by one servant and offered more refreshment by others.

Musicians play and dancers twirl around a fountain. Filling all available space between the figures are the plants and flowers of the garden. This is a beautiful and lavish image, dominated by rich, saturated colors, evoking the pleasurable paradise of the gardens.

Sur, Celebrations in honour of the birth of Humayun in the Chahar Bagh of Kabul (1508), c. 1590, Mughal Empire, opaque watercolor on paper (The British Library)

Monet’s painting of the gardens at Giverny: converging microcosms

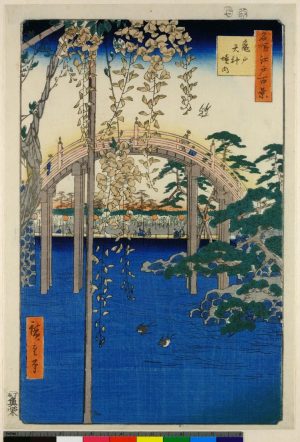

Utagawa Hiroshige, “Wisteria at Kameido Tenjin Shrine” from One Hundred Famous Views in Edo, 1856, woodblock print (British Museum, London)

In Claude Monet’s famous gardens at Giverny, in northern France, many of the threads of this discussion come together.

This is a garden, in part inspired by Japanese gardens (in turn inspired by Chinese gardens), which was designed not only to provide pleasure but also to serve as the basis for Monet’s own paintings. Monet was a collector of Japanese woodblock prints, and from them he learned to favor the asymmetry of Asian gardens over the symmetry of traditional French gardens, like those at Versailles.

In a particularly picturesque section of the garden, he constructed an arching bridge like those found in Chinese and Japanese gardens, over a pond filled with water lilies, as we can see in Utagawa Hiroshige, “Wisteria at Kameido Tenjin Shrine.” The pond is surrounded by heavy plantings, weeping willows that hang low over the water, Japanese maples, with their rich red leaves, and other plants. The waters are, in season, filled with the water lilies that Monet loved to paint.

Lilla Cabot Perry, Bridge in Giverny, France, 1899-1909, photograph, 3 7/8 x 5 1/8 inches (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Turning to Monet’s Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge (1896-1899), we see nearly the same view, with the arch of the bridge slightly exaggerated for effect. The colors are pastel, bright and cheerful. The light—which is a major focus of Monet’s work—is strong, as if it is a sunny summer day. The brushwork is very loose, with each stroke visible on the surface of the canvas.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge, 1899, oil on canvas, 90.5 x 89.7 cm (35 5/8 x 35 5/16 inches) (Princeton University Art Museum)

The result is not a precise botanical illustration, but rather, a gentle image that conveys the pleasant atmosphere of the garden. Though the gardens themselves are asymmetrical, Monet follows European painting conventions by framing the bridge in such a way as to create a symmetrical image, enlivened by small differences in the plants around the bridge, and in the shadows that fall more heavily on the right side of the image than on the left.

The symmetry helps the desired effect: everything in the garden, and in the painting of it, speaks of calm, restful beauty. Monet’s paintings of his garden at Giverny are among the most popular works of art in the world, frequently reproduced as posters that are common to college dorm rooms. Similarly, the gardens themselves attract over half a million tourists each year, drawn by the beautiful views, and by travelers’ prior experience of them through Monet’s paintings.

The gardens and images of gardens explored here show that, across cultures and across time, gardens have represented microcosms of desirable worlds, from realms of political power and control to the inner worlds of the enlightened.

Notes

[1] Judith B. Tankard, Gertrude Jekyll and the Country House Garden (New York: Rizzoli, 2011), p. 9.

[2] Judith B. Tankard, Gertrude Jekyll and the Country House Garden (New York: Rizzoli, 2011), p. 11.

[3] Judith B. Tankard, Gertrude Jekyll and the Country House Garden (New York: Rizzoli, 2011), p. 21.

Additional resources: