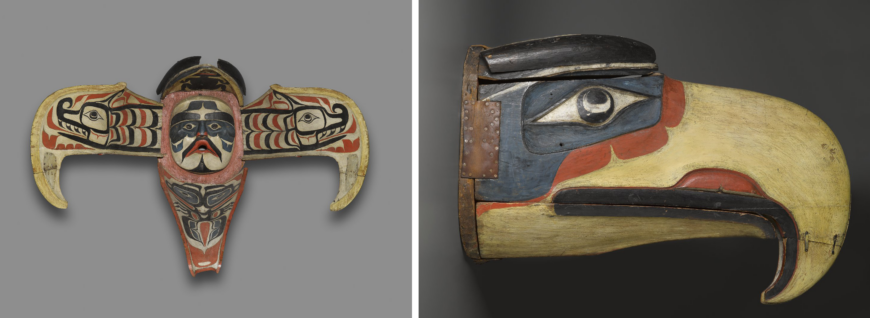

Kwakwaka’wakw artist, Eagle Mask closed, late 19th century (Alert Bay, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada), cedar wood, feathers, sinew, cord, bird skin, hide, plant fibers, cotton, iron, pigments, 37 x 57 x 49 cm (American Museum of Natural History, New York)

Transformation

Imagine a man standing before a large fire wearing the heavy eagle mask shown above and a long cedar bark costume on his body. He begins to dance, the firelight flickers and the feathers rustle as he moves about the room in front of hundreds of people. Now, imagine him pulling the string that opens the mask, he is transformed into something else entirely—what a powerful and dramatic moment!

Kwakwaka’wakw artist, Eagle Mask open, late 19th century (Alert Bay, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada), cedar wood, feathers, sinew, cord, bird skin, hide, plant fibers, cotton, iron, pigments, 37 x 57 x 49 cm (American Museum of Natural History, New York)

Northwest Coast transformation masks manifest transformation, usually an animal changing into a mythical being or one animal becoming another. Masks are worn by dancers during ceremonies, they pull strings to open and move the mask—in effect, animating it. In the Eagle mask shown above from the collection of the American Museum of Natural History, you can see the wooden frame and netting that held the mask on the dancer’s head. When the cords are pulled, the eagle’s face and beak split down the center, and the bottom of the beak opens downwards, giving the impression of a bird spreading its wings. Transformed, the mask reveals the face of an ancestor.

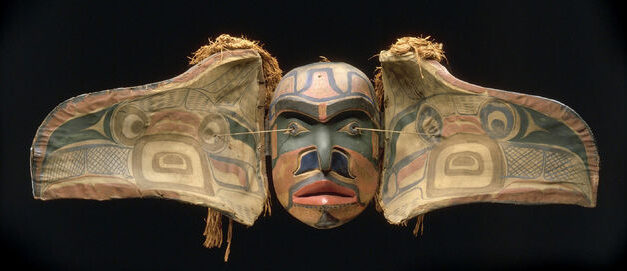

Open and closed views, ʼNa̱mǥis artist (of the Kwakwaka’wakw), Thunderbird Mask, 19th century (Alert Bay, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada), cedar, pigment, leather, nails, metal plate, 78.7 x 114.3 x 119.4 cm open; 52.1 x 43.2 x 74.9 cm closed (Brooklyn Museum)

A Transformation Mask at the Brooklyn Museum shows a Thunderbird, but when opened it reveals a human face flanked on either side by two lightning snakes called sisiutl, with another bird below it, and with a small figure in black above it.

Kwakwaka’wakw artist, Whale Mask, 19th century (Alert Bay, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada), cedar wood, cord, metal, leather, denim, pigments, 58 x 36.5 x 161.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; photo: Peter Roan, CC BY-NC 2.0)

A whale transformation mask, such as the one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gives the impression that the whale is swimming. The mouth opens and closes, the tail moves upwards and downwards, and the flippers extend outwards but also retract inwards.

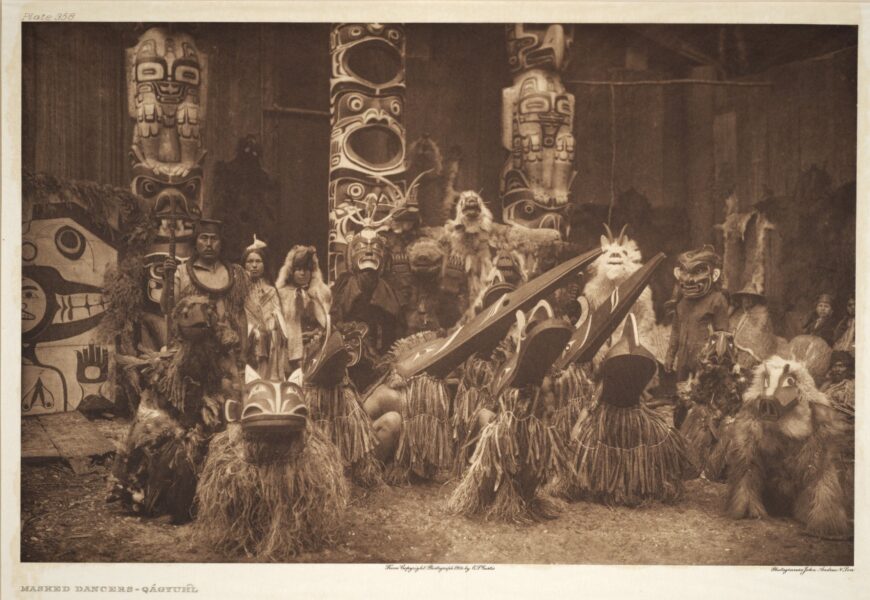

Transformation masks, like those belonging to the Kwakwaka’wakw (pronounced Kwak-wak-ah-wak, a Pacific Northwest Coast Indigenous people) and illustrated here, are worn during a potlatch, a ceremony where the host displayed his status, in part by giving away gifts to those in attendance. These masks were only one part of a costume that also included a cloak made of red cedar bark. During a potlatch, Kwakwaka’wakw dancers perform wearing the mask and costume. The masks conveyed social position (only those with a certain status could wear them) and also helped to portray a family’s genealogy by displaying (family) crest symbols.

The Kwakwaka’wakw

Masks are not the same across the First Nations of the Northwest Coastal areas; here we focus solely on Kwakwaka’wakw transformation masks.

The Kwakwaka’wakw (“Kwak’wala speaking tribes”) are generally called Kwakiutl by non-Native peoples. They are one of many Indigenous groups that live on the western coast of British Columbia, Canada. The mythology and cosmology of different Kwakwaka’wakw Nations (such as the Kwagu’ł (Kwakiutl) or ʼNa̱mǥis) is extremely diverse, although there are commonalities. For instance, many groups relate that deceased ancestors roamed the world, transforming themselves in the process (this might entail removing their animal skins or masks to reveal their human selves within).

Kwakwaka’wakw bands are arranged into four clans (Killer Whale, Eagle, Raven, and Wolf clans). The clans are divided into numayn (or ‘na’mina), which can be loosely translated as “group of fellows of the same kind” (essentially groups that shared a common ancestor). Numayns were responsible for safe-guarding crest symbols and for conveying their specific rights—which might include access to natural resources (like salmon fishing areas) and rights to sacred names and dances that related to a numayn’s ancestor or the group’s origins. The numayn were ranked, and typically only one person could fill a spot at any given moment in time. Each rank entailed specific rights, including ceremonial privileges—like the right to wear a mask such as the Brooklyn Museum’s Thunderbird transformation mask. Animal transformation masks contained crests for a given numayn. Ancestral entities and supernatural forces temporarily embody dancers wearing these masks and other ceremonial regalia.

Transformation Mask, Kwakiutl population, 19th century (British Columbia, Canada), wood paint, graphite, cedar, cloth, string, 34 x 53 cm closed, 130 cm open (Quai Branly Museum, Paris). “This transformation mask opens into two sections. Closed, it represents a crow or an eagle; when spread out, a human face appears. It was associated with initiation rites that took place during the winter. During these ceremonies, both religious and theatrical, the spirit of the ancestors was supposed to enter into men.”

Animals and myths

Many myths relate moments of transformation often involving trickster supernaturals. Raven, for instance, is known as a consummate trickster—he often changes into other creatures, and helps humans by providing them with a variety of useful things such as the sun, moon, fire, and salmon. Thunderbird (Kwankwanxwalige’), who was a mythical ancestor of the Kwakwaka’wakw, also figures prominently in mythology. He is believed to cause thunder when he beats his wings and lightning comes from his eyes. He lives in the celestial realm, and he can remove his bird skin to assume human form.

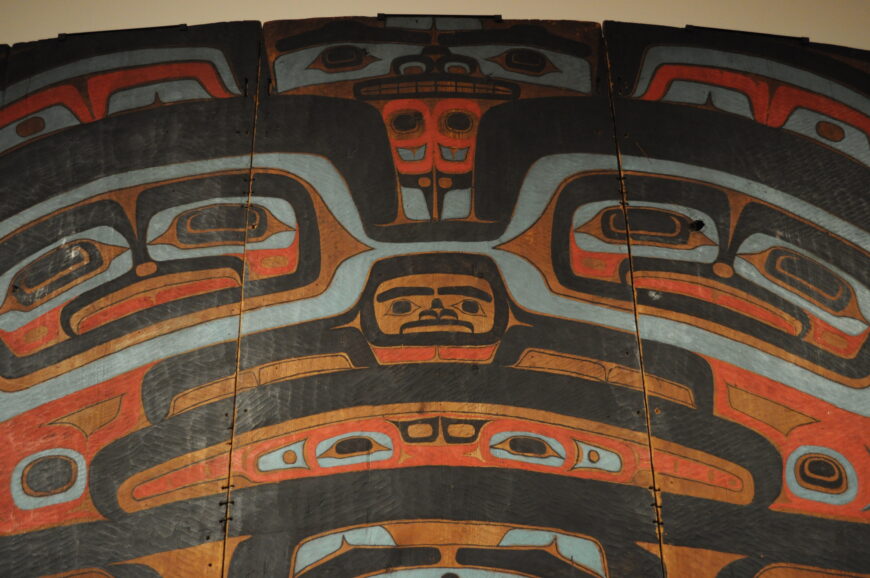

Bilaterally symmetrical masks (detail), Tlingit Raven Screen or Yéil X’eenh, attributed to Kadyisdu.axch’, Tlingit, Kiks.ádi clan, active late 18th–early 19th century (Seattle Art Museum; photo: Joe Mabel, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Design and materials

The masks illustrated here display a variety of brightly colored surfaces filled with complex forms. These masks use elements of the formline style, a term coined in 1965 to describe the characteristics of Northwest Coast visual culture. The Brooklyn Museum mask provides a clear example of what constitutes the formline style. For instance, The Brooklyn Museum mask (when open) displays a color palette of mostly red, blue-green, and black, which is consistent with other formline objects like a Tlingit Raven Screen (a house partition screen) attributed to Kadyisdu.axch’. The masks, whether opened or closed, are bilaterally symmetrical. Typical of the formline style is the use of an undulating, calligraphic line. Also, note how the pupils of the eyes on the exterior of the Brooklyn Museum mask are ovoid shapes, similar to the figures and forms found on the interior surfaces of many masks. This ovoid shape, along with s- and u-forms, are common features of the formline style.

The American Museum of Natural History and Brooklyn Museum masks are carved of red cedar wood, an important and common material used for many Northwest Coast objects and buildings. Masks take months, sometimes years, to create. Because they are made of wood and other organic materials that quickly decay, most masks date to the 19th and 20th centuries (even though we know that the practice extends much farther into the past). In fact, the artistic style of many transformation masks it thought to have emerged over a thousand years ago.

With the introduction and enforcement of Christianity and as a result of colonization in the 19th century, masking practices changed among peoples of the Northwest Coast. Prior to contact with Russians, Europeans, and Euro-Americans, masks like the Brooklyn Museum’s Thunderbird Transformation Mask were not carved using metal tools. After iron tools were introduced along with other materials and equipment, masks demonstrate different carving techniques. Earlier masks used natural (plant and mineral based) pigments, but post-contact, brighter and more durable synthetic colors were introduced. The open mask from the American Museum of Natural History, for example, displays bright red, yellow, and blue.

Ceremonies and potlatches

Masks passed between family members of a specific clan (they could be inherited or gifted). They were just one sign of a person’s status and rank, which were important to demonstrate within Kwakwaka’wakw society—especially during a potlatch. Franz Boas, an anthropologist who worked in this area between 1885 and 1930, noted that “The acquisition of a high position and the maintenance of its dignity require correct marriages and wealth—wealth accumulated by industry and by loaning out property at interest—dissipated at the proper time, albeit with the understanding that each recipient of a gift has to return it with interest at a time when he is dissipating his wealth. This is the general principle underlying the potlatch….” [1]

Edward S. Curtis, Kwakwaka’wakw potlatch, c. 1914 (Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington, D.C.)

Potlatches were banned in 1885 until the 1950s because they were considered immoral by Christian missionaries who believed cannibalism occurred (for its part, the Canadian Government thought potlatches hindered economic development because people ceased work during these ritual celebrations). With the prohibition of potlatches, many masks were confiscated. Those that weren’t destroyed often made their way into museums or private collections. When the ban against potlatches was removed by the Canadian government, many First Nations have attempted to regain possession of the masks and other objects that had been taken from them. Potlatches are still practiced today among Northwest Coast peoples.

Editor Note: In the United States, it is more common to see the term “Native American,” “Native,” or “Indigenous,” whereas “First Nations” used more frequently in Canada.