Made of silk, pearls, gems, and gold, Roger II’s mantle tells a story of Mediterranean connectivity in Norman Sicily.

Mantle of Roger II, 1133/34 (Norman Sicily, Italy), textiles, patterned samite (kermes dye), gold and silk embroidery, pearls, gold with cellular enamel, rubies, spinels, sapphires, garnets, glass, tablet weave, 146 x 345 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re in the Hofburg in Vienna, in the royal treasury, which is filled with crowns and scepters…

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:12] Reliquaries and jewels. It’s amazing.

Dr. Zucker: [0:15] And one of the real treasures is an enormous mantle that was worn during the coronations of the Holy Roman emperors, but that’s not what this was made for. This was made in the 12th century in Sicily, actually, in the royal workshops of Roger II, who was a Norman that ruled. Now, the Normans, you might remember, actually began as Vikings.

[0:37] They came down from the north and they eventually settled in northwestern France, and also at the bottom of Italy, and the island of Sicily. That’s where this was made.

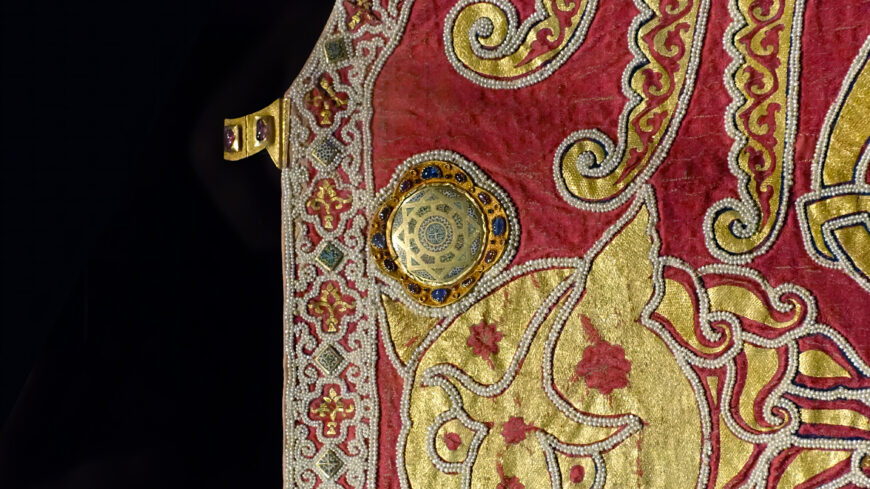

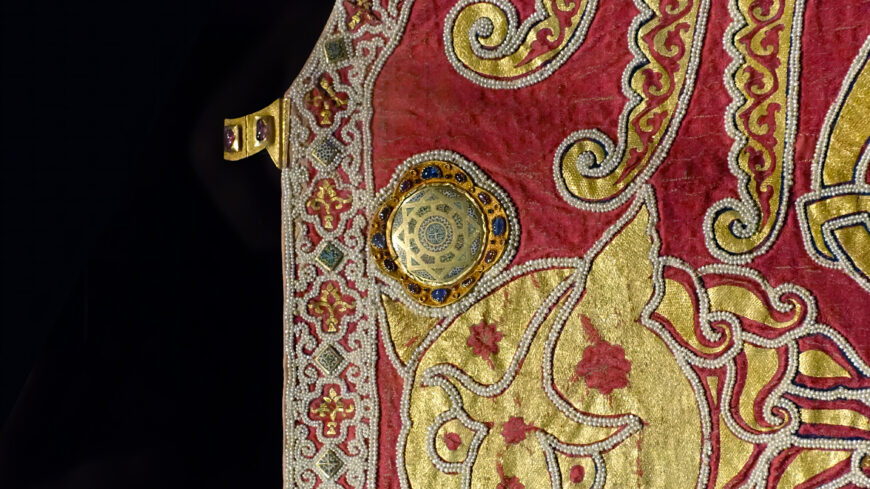

Dr. Harris: [0:46] This is a really large cloak. You can see the clasps at the top for where it would have been worn over the shoulders. It’s made of red silk, gold stitching, and thousands of pearls and enamel plates and jewels.

Dr. Zucker: [1:02] It’s in exceptional condition. The enamel is made in cloisonné, where very fine walls of gold separate the enamels themselves as they melt, as they vitrified. What’s so interesting about this mantle is if you look at its imagery, even though it was made for a Christian ruler, it’s full of Islamic motifs. It was made by Islamic artisans.

Dr. Harris: [1:23] We see that in the lion overpowering a camel. We see it in the calligraphic script along the semicircular bottom and the Tree of Life in the center.

Dr. Zucker: [1:33] A motif almost identical to that in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. These are motifs that come out of pattern books that would have transversed the Islamic world and were copied over hundreds of years.

Dr. Harris: [1:44] The robe was clearly meant to symbolize power. Look at the forms of those lions. They’re schematic and not terribly naturalistic, but they evoke a real sense of fierceness in their faces and their puffed-out chests. And the camels look so subdued and overpowered.

Dr. Zucker: [2:02] Those camels are domesticated. They’re actually wearing saddles. One of the interpretations of this iconography, of the symbolism, is that the lions are representing the Normans — the house of Roger II had as its symbol the lion — whereas the camel might be a reference to peoples that Roger had conquered.

Dr. Harris: [2:20] So although this cloak was made in the 12th century, it acquired the legend that it was made for Charlemagne, for the very first Holy Roman Emperor in the 9th century.

Dr. Zucker: [2:30] We know that that’s not the case because in fact, the Kufic inscription — Arabic writing — gives us a specific date.

Dr. Harris: [2:37] “This mantle is worked in the most magnificent royal splendor, perfection, might, superiority, approval, prosperity, magnanimity, beauty, the fulfillment of all desires and hopes, felicitous days and nights without cease or change, with authority, with honor, freedom from harm, triumph, and livelihood, in the city of Sicily in the year 528.”

Dr. Zucker: [3:02] 528, according to the Islamic calendar, dating from the time of Muhammad, this correlated with the 12th century in the Western calendar. Those plates also have an important iconography that has an Islamic origin. You’ll see a star that’s made out of the intersection of two squares.

[3:18] Going back to the beginning of Islam, there was a notion that the earth was a square and the heavens were a square. Here we see those overlaid, and so you do have a cosmological reference, and perhaps a reference that Roger himself ruled over all.

Dr. Harris: [3:33] There’s a clear sense here of speaking to the owner’s grandeur.

Dr. Zucker: [3:38] Just imagine, through history, those that were crowned Holy Roman Emperor wearing this garment, carrying an orb, carrying a scepter, the pope, a huge ensemble of the most powerful people in the West. It must have been quite a sight to see.

[3:54] [music]

Mantle of Roger II, 1133/34 (Norman Sicily, Italy), textiles, patterned samite (kermes dye), gold and silk embroidery, pearls, gold with cellular enamel, rubies, spinels, sapphires, garnets, glass, tablet weave, 146 x 345 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, XIII 14; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Standing before the Mantle of Norman King Roger II in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, visitors encounter one of the most remarkably preserved medieval textiles: a semicircular cloak of luminous red silk, embroidered with gold thread and thousands of pearls and gemstones, depicting lions subduing camels flanking a stylized palm tree. An Arabic inscription in elegant Kufic script curves along its hem, proclaiming:

Of what was made in the khizāna (treasury), regal and plentiful, with happiness and honor, and good fortune and perfection, and long life and profit, and welcome and prosperity, and generosity and splendor, and glory and beauty, and realisation of desires and hopes, and delights of days and nights, without end and without modification, with might and care, and sponsorship and protection, and happiness and well-being, and triumph and sufficiently. In the city of Sicily, in the year 528.translation from Isabelle Dolezalek, Arabic Script on Christian Kings: Textile Inscriptions on Royal Garments from Norman Sicily (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017), p. 9

For centuries, the Eastern Roman Byzantine Empire and then Islamic rulers governed Sicily before Norman invaders from Northern France conquered the island in 1091 and established the Norman Kingdom of Sicily. Although the Norman kings were Latin Christians, they now governed a diverse population of Muslims, Arab- and Greek-Christians, and Jews. Why would Roger II, a Latin Christian ruler of this new kingdom, commission such a remarkable mantle with Arabic epigraphy as his most precious royal textile? The answer lies in understanding how the mantle was used and how the kingdom’s many audiences would have understood its complex layers of meaning.

Clasp and medallion (detail), Mantle of Roger II, 1133/34 (Norman Sicily, Italy), textiles, patterned samite (kermes dye), gold and silk embroidery, pearls, gold with cellular enamel, rubies, spinels, sapphires, garnets, glass, tablet weave, 146 x 345 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, XIII 14; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A Mediterranean object

The mantle defies simple categorization. Its Arabic inscription dates it to the Islamic hijri year 528 (1133–34 C.E.) and identifies its creation in Palermo’s royal workshop, staffed by both Christian and Muslim artisans. Yet its semicircular form follows conventions of Byzantine and Latin ceremonial regalia, resembling both the Byzantine chlamys worn by emperors during secular ceremonies and semicircular mantles worn by Latin Christian rulers like the Star Mantle of Henry II. Its imagery draws from a visual vocabulary shared across Mediterranean courts, while its materials tell stories of far-flung trade networks and diplomatic connections.

Two lions trample two camels, separated by a central palm tree. Although the motif of a lion triumphant over another animal was common across the medieval Mediterranean—appearing on Byzantine silks, Islamic portable objects, and Romanesque sculpture—the choice of a camel as the defeated animal is highly unusual. The substitution may carry pointed political meaning. According to a later account, Roger’s father, Roger of Hauteville, sent Pope Alexander II four camels captured as booty after the 1063 Battle of Cerami, where Norman forces triumphed over Arab and North African troops. In this context, the mantle’s lions trampling camels could have deliberately evoked Norman victories over Muslim rulers in Sicily and North Africa.

The practice of Arabic inscribed textiles, known as tirāz, had deep political significance. They were distributed to courtiers and individuals of merit or used as diplomatic gifts, their inscriptions marking the ruler’s power. While the inscription on Roger’s mantle does not follow standard tirāz inscriptions (which typically name the caliph and invoke religious authority), it draws on the same tradition likewise evoking royal authority and legitimacy. Stylistically, the inscription is closest to inscriptions from pre-Norman Islamic Sicily and Ifriqiya (North Africa), suggesting both continuity with the island’s Islamic past and a distinctive Norman adaptation.

In Roger’s Sicily, where the king governed a multiethnic and multilingual population, the mantle’s imagery would have communicated differently to different audiences. For Latin Christians it might have evoked triumph; for Arabic-speaking courtiers, the lion and palm tree imagery may have demonstrated the king’s participation in Mediterranean court culture; for Greek-speaking subjects, it may have recalled Byzantine imperial imagery and notions of paradise. The mantle’s power lay precisely in this multiplicity—its capacity to mean many things to many people simultaneously.

Clasp and medallion (detail), Mantle of Roger II, 1133/34 (Norman Sicily, Italy), textiles, patterned samite (kermes dye), gold and silk embroidery, pearls, gold with cellular enamel, rubies, spinels, sapphires, garnets, glass, tablet weave, 146 x 345 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, XIII 14; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Materials and networks

Its materials tell a story of Mediterranean connectivity. The red samite silk that forms the base fabric likely came from the Byzantine Empire, possibly imported pre-woven. [1] The gold threads are of exceptionally high purity, significantly richer than other contemporaneous Sicilian textiles, and their technique of wrapping thin metal strips around a yellow silk core represents Byzantine expertise that Sicily did not yet possess. [2] Like the silk, these threads may have also come from Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire.

Pearls (detail), Mantle of Roger II, 1133/34 (Norman Sicily, Italy), textiles, patterned samite (kermes dye), gold and silk embroidery, pearls, gold with cellular enamel, rubies, spinels, sapphires, garnets, glass, tablet weave, 146 x 345 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, XIII 14)

The pearls presented their own logistical challenges. Thousands were required for the embroidery. They were likely sourced through long-distance trade networks connecting the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf and beyond. Each pearl had to be pierced and stitched individually, a labor-intensive process that proclaimed the workshop’s technical mastery and the patron’s economic power. [3] Enamel plaques and gemstones (garnets, glass, rubies, and sapphires) completed the decoration, products of the royal enamel workshop in Palermo that also created works for the Cappella Palatina and other Norman monuments.

These were among the most expensive and luxurious materials available. The expense, effort, and networks necessary to acquire them created a garment that displayed not just wealth, but the geographic reach of the Norman kingdom and the king’s ability to foster trade networks across the Mediterranean and beyond.

Camel (detail), Mantle of Roger II, 1133/34 (Norman Sicily, Italy), textiles, patterned samite (kermes dye), gold and silk embroidery, pearls, gold with cellular enamel, rubies, spinels, sapphires, garnets, glass, tablet weave, 146 x 345 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, XIII 14; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Function and performance

Although it has long been described as King Roger II’s “coronation mantle,” the actual function of this garment remains uncertain. The embroidered inscription clearly dates it to 1133–34, three years after Roger’s coronation in 1130. Moreover, the mantle shows remarkably little evidence of wear, suggesting that it was rarely, if ever, used in regular court display. How then do we account for the commission of such a magnificent textile?

Several possibilities have been proposed. The first situates the mantle within Roger’s efforts to secure his dynastic succession in the early 1130s. During this period, he invested his three eldest sons with strategic titles: Roger III as Duke of Apulia, Tancred as Prince of Bari, and Alfonso as Prince of Capua. Such ceremonies would have required appropriate regalia—perhaps the mantle was commissioned just for these purposes, designed to project royal authority and continuity. [4] Imagine such a ceremony: as the prince knelt before his father, the vast mantle spread out around him, its pearls and gold embroidery catching the light before the assembled witnesses—a material performance of legitimacy and inherited sovereignty.

Others have suggested that the mantle was made to be used as Roger’s shroud, or burial garment, on the occasion of his death. William Tronzo has noted that the mantle’s iconography, with its paired lions in combat, recalls motifs common on Roman imperial sarcophagi. [5]

Sarcophagus, late 2nd–early 3rd century C.E. (Roman; Sicily, Italy) (Museo Diocesano di Monreale; photo: Alex Brey, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Porphyry sarcophagus (a gift of Roger II to the Cathedral of Cefalù), 12th century (Sicily, Italy), later used as the tomb of Frederick II (Palermo Cathedral; photo: Bernard Blanc, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The connection gains further plausibility from Roger’s own donations to the Cathedral of Cefalù in 1145: two monumental sarcophagi, one Roman, eventually used as the first tomb of Roger’s grandson King William II, and a second porphyry sarcophagus originally intended as his own tomb. [6] At the time of his death in 1154, Cefalù Cathedral had not yet been consecrated and his remains were interred in a more modest porphyry sarcophagus in Palermo Cathedral. Yet the paired lions in combat on both tombs, ancient and medieval, bear striking resonances with the mantle’s imagery, suggesting the textile could have been conceived as part of a broader program of royal commemoration. Ultimately, Roger was not buried in the mantle itself; instead, it entered the collection of royal garments inherited by his descendants and eventually the Holy Roman Emperors.

While we may never know the mantle’s precise function, in whatever context it appeared, it materialized and perpetuated the image of sovereign power.

Lion, camel, and inscription (detail), Mantle of Roger II, 1133/34 (Norman Sicily, Italy), textiles, patterned samite (kermes dye), gold and silk embroidery, pearls, gold with cellular enamel, rubies, spinels, sapphires, garnets, glass, tablet weave, 146 x 345 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, XIII 14; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Visibility and legibility

The Kufic script along the mantle’s hem is exceedingly clear and beautifully formed, yet how many people could actually read it? Even among Roger’s multilingual court, Arabic literacy was limited to specific communities: Muslim subjects and chancery officials.

Consider how the mantle would actually have been worn—not as it is displayed in Vienna today, suspended in space, but draped over a human body. The central palm tree would have appeared at the center of the wearer’s back. The heads of the animals, along with the intricate patterns of precious pearls and enamel work, would have been most visible at the front, framing the wearer’s body. The inscription, however, would have been largely obscured by the natural folds of the draped fabric, visible only on either side of the vertical axis formed by the wearer’s back. The factual information—where and when it was made—would have appeared at the front, while the central poetic praise of the royal workshop fell along the king’s back, often hidden from view.

The mantle’s inscription employs an Arabic literary form known as sajʿ, rhythmically structured prose connected through rhymes, specifically intended to be recited aloud before an audience. The inscription was not meant to be read silently, but performed aloud. During investiture ceremonies or other court rituals, someone, perhaps a court official or poet, could have recited the inscription’s praises, transforming the textile from material object into acoustic praise. Even for those who could not read Arabic, the luminosity of the golden script, moving and catching light as it draped over the wearer’s body would have been highly visible and impressive. [7]

Interior lining with intertwined serpents (detail), Mantle of Roger II, 1133/34 (Norman Sicily, Italy), textiles, patterned samite (kermes dye), gold and silk embroidery, pearls, gold with cellular enamel, rubies, spinels, sapphires, garnets, glass, tablet weave, 146 x 345 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, XIII 14; photo: Sara Kuehn)

The hidden interior: serpents and protection

While the exterior of the mantle commands immediate attention, the interior textiles tell an equally compelling story. The lining consists of five separate sections, composed of fragments from three different precious textiles, commonly referred to as the “fabric of the birds,” the “fabric of the dragons,” and the “fabric of the tree of life.” All three are tapestry-woven silks interwoven with gold thread.

Two of these textiles belong to a corpus thought to have been produced in Palermo from the 10th century onward, while one appears to have originated in Khurasan in Central Asia. This combination of textiles from different periods and places was certainly deliberate. The palace workshop likely maintained a treasury of fabrics, acquired through diplomatic gifts, inherited from previous rulers, or taken as spoils of war, which could be drawn upon for special commissions. [8] The choice to line the new mantle with these older, prestigious textiles physically incorporated Sicily’s layered past into its Norman present.

But the most intriguing aspect of the lining is its dominant motif: intricately knotted serpents. These ophidian forms appear across all three textiles in complex, intertwined patterns—elaborate lattices and knots, bodies looping around stylized trees and forming heart-shaped interlaces, and drinking from vessels.

Serpentine fountain (detail), illustration from a 12th-century manuscript copy of Saint Gregory of Nazianzus’s 4th-century homilies (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Grec 550, folio 166 verso)

In the medieval Mediterranean, serpents carried ambivalent meanings. Some Christian traditions associated them with evil and temptation, recalling the biblical serpent in the Garden of Eden. Yet Byzantine sources also connected them with water, healing, and protection. Serpents drinking from fountains appeared frequently in Byzantine art, especially in imagery of fountains and basins, as symbols of eternal life, their intertwined bodies suggesting continuous, unending flow. They also appeared as apotropaic symbols, as guardians offering protection.

The lining’s serpentine imagery takes on additional resonance if the mantle were intended for a funerary context. With their associations of eternal protection and the water of life, the serpents would serve as threshold guardians, accompanying the deceased ruler in his transition to the afterlife. Their multiplication across multiple textiles reinforced their protective power. [9]

Reproduction of a gold-woven textile from the shroud found in the sarcophagus of Roger II, Palermo, Sicily. Francesco la Marra, plate C, engraving, from Francesco Daniele, I regale sepolcri del duomo di Palermo, 1784 (Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles)

Evidence supports this interpretation. Between 1781 and 1799, Roger’s sarcophagus was unsealed in Palermo Cathedral and fragments of his burial attire were discovered. An 18th-century drawing and description survive, showing his burial mantle, decorated with a pattern of intertwined serpents remarkably similar to those on the Vienna mantle’s lining. The contrast between exterior and interior becomes meaningful: the exterior proclaimed authority to living audiences through familiar Mediterranean imagery, while the interior provided spiritual protection. The mantle thus could have been intended to operate on multiple planes simultaneously: political and spiritual, visible and hidden, for the living and for eternity.

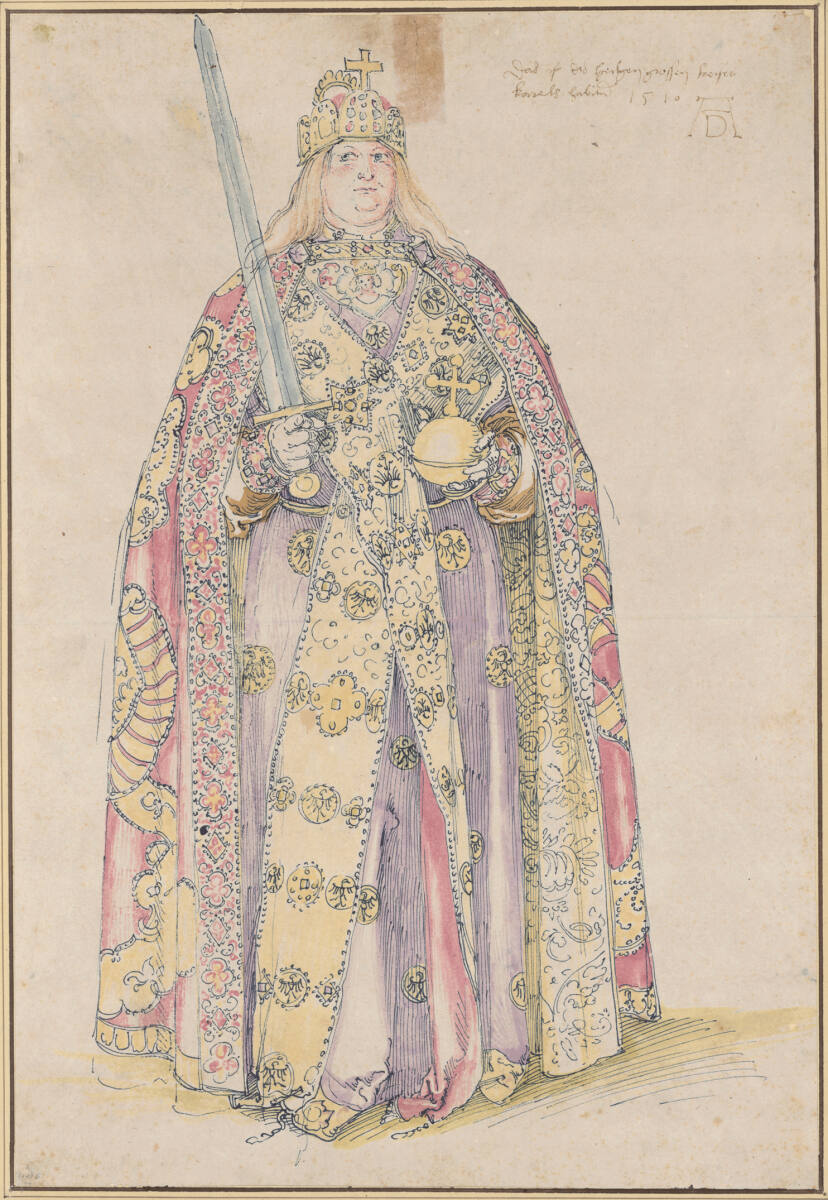

Albrecht Dürer, Karl der Große (Charlemagne), 1510, ink and watercolor, 41.5 x 28.4 cm (The Albertina Museum, Vienna)

An object of many lives

Throughout its subsequent history, the mantle continued to accrue new meanings and associations. It entered the Holy Roman Empire’s coronation regalia through Frederick I, Roger II’s grandson, gaining new associations through its use in the coronation ceremonies of German emperors.

Franz von Matsch, Ankeruhr Clock, Hoher Markt, Vienna, Austria, 1914 (photo: Rizka, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In 1510, Dürer created an imaginary and anachronistic portrait of Charlemagne wearing the mantle, cementing its iconic status for centuries to come. The connection became so embedded in Viennese culture that in the early 20th century, the artist Franz von Matsch incorporated the figure of Charlemagne wearing Roger’s mantle into a monumental mechanical clock on Hoher Markt, one of Vienna’s oldest squares. Every day at 2 PM, the Carolingian emperor appears wearing the iconic Norman mantle, a daily performance that continues to this day.