Viewing the Bayeux tapestry at the Bayeux Tapestry Museum; Bayeux tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Museum; photo: boris doesborg, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Measuring twenty inches high and almost 230 feet in length, the Bayeux Tapestry commemorates a struggle for the throne of England between William, the Duke of Normandy, and Harold, the Earl of Wessex. The year was 1066—William invaded and successfully conquered England, becoming the first Norman King of England (he was also known as William the Conqueror).

The Bayeux Tapestry consists of seventy-five scenes with Latin inscriptions (tituli) depicting the events leading up to the Norman conquest and culminating in the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The textile’s end is now missing, but it most probably showed the coronation of William as King of England.

Falconer (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

Although it is called the Bayeux Tapestry, this commemorative work is not a true tapestry as the images are not woven into the cloth; instead, the imagery and inscriptions are embroidered using wool yarn sewed onto linen cloth.

The tapestry is sometimes viewed as a type of chronicle. However, the inclusion of episodes that do not relate to the historic events of the Norman Conquest complicate this categorization. Nevertheless, it presents a rich representation of a particular historic moment as well as providing an important visual source for eleventh-century textiles that have not survived into the twenty-first century.

Normans with horses on boats, crossing to England, in preparation for battle (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

The Bayeux Tapestry was probably made in Canterbury around 1070. Because the tapestry was made within a generation of the Norman defeat of the Anglo-Saxons, it is considered to be a somewhat accurate representation of events. Based on a few key pieces of evidence, art historians believe the patron was Odo, Bishop of Bayeux. Odo was the half-brother of William, Duke of Normandy. Furthermore, the tapestry favorably depicts the Normans in the events leading up to the battle of Hastings, thus presenting a Norman point of view.

Bishop Odo rallying William the Conqueror’s troops at the Battle of Hastings (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum)

Most importantly, Odo appears in several scenes in the tapestry with the inscription ODO EPISCOPUS (abbreviated “EPS” in the image above), although he is only mentioned briefly in textual sources. By the late Middle Ages, the tapestry was displayed at Bayeux Cathedral, which was built by Odo and dedicated in 1077, but its size and secular subject matter suggest that it may have been intended to be a secular hanging, perhaps in Odo’s hall.

We do not know the identity of the artists who produced the tapestry. The high quality of the needlework suggests that Anglo-Saxon embroiderers produced the tapestry. At the time, Anglo-Saxon needlework was prized throughout Europe. This theory is supported by stylistic analysis of the depicted scenes, which draw from Anglo-Saxon drawing techniques. Many of the scenes are believed to have been adapted from images in manuscripts illuminated at Canterbury.

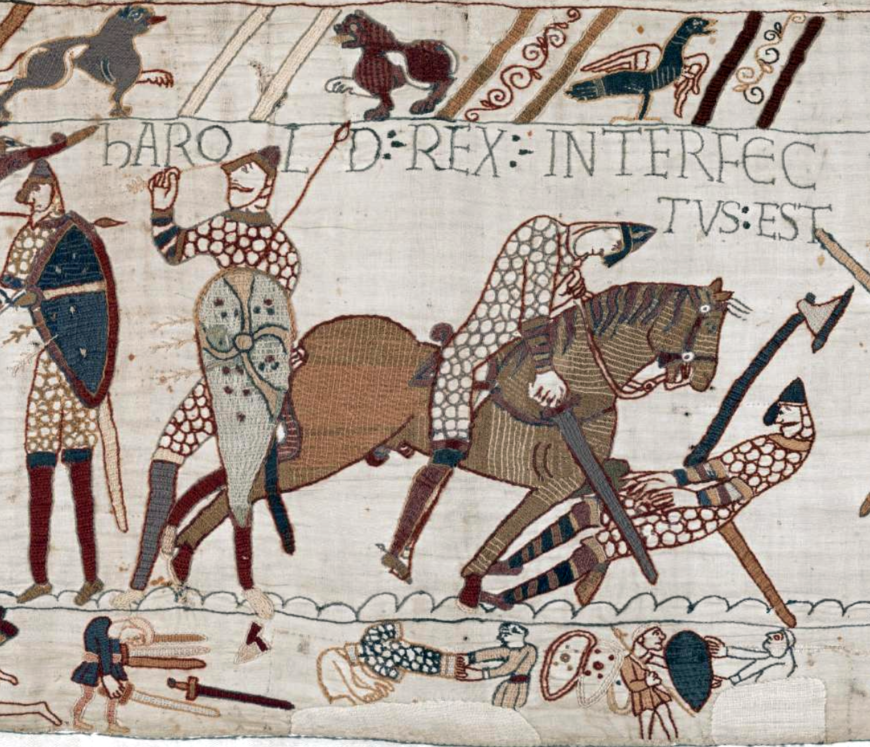

The death of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

The artists skillfully organized the composition of the tapestry to lead the viewer’s eye from one scene to the next and divided the compositional space into three horizontal zones. The main events of the story are contained within the larger middle zone. The upper and lower zones contain images of animals and people, scenes from Aesop’s Fables, and scenes of husbandry and hunting. At times the images in the borders interact with and draw attention to key moments in the narrative (as in the image above of the battle).

The seventy-five episodes depicted present a continuous narrative of the events leading up to the Battle of Hastings and the battle itself. A continuous narrative presents multiple scenes of a narrative within a single frame and draws from manuscript traditions such as the scroll form. The subject matter of the tapestry, however, has more in common with ancient monumental decoration such as Trajan’s Column, which typically focused on mythic and historical references.

Servants preparing food (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

The embroiderers’ attention to specific details provides important sources for scenes of eleventh-century life as well as objects that no longer survive. In one scene of the Normans’ first meal after reaching the shores of England, we see dining practices. We also see examples of armor used in the period and battle preparations. To the left of the dining scene, servants prepare food over a fire and bake bread in an outdoor oven (above). Servants serve the food as the tapestry’s assumed patron, Bishop Odo, blesses the meal (below).

The Normans’ first meal in England, at the center is Bishop Odo, who gazes out as he offers a blessing over the cup in his hand.(detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

Immediately after dining, William and his half-brothers Odo and Robert meet for a war council. Preparations for battle flank both sides of the first meal episode (below).

Preparations for war, including the building of a motte-and-bailey (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

Here we see visual evidence of eleventh-century battle gear and the construction of a motte-and-bailey to protect the Normans’ position. A motte-and-bailey is a fortification with a keep (tower) situated on a raised earthwork (motte), surrounded by an enclosed courtyard (bailey). Images of battle horns, shields, and arrows as crucial ammunition shed light on military provisions and tactics for the time period.

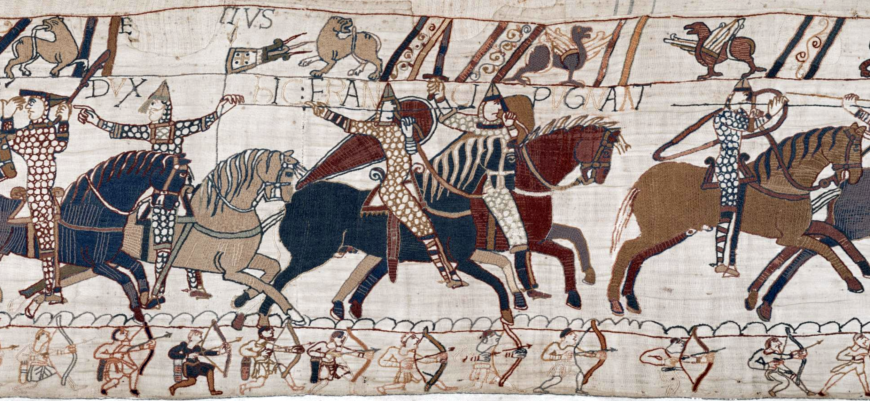

Cavalry and foot soldiers in battle (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

William’s tactical use of cavalry is displayed in the “Cavalry” scene. The cavalry could advance quickly and easily retreat, which would scatter an opponent’s defenses allowing the infantry to invade. It was a strong tactic that was flexible and intimidating. Although foot soldiers are included in the tapestry, the cavalry commands the scene, thus presenting the impression that the Normans were a cavalry-dominant army.

Wounded soldiers and horses (detail), Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1070, embroidered wool on linen, 20 inches high (Bayeux Tapestry Museum, Official digital representation of the Bayeux Tapestry—11th century. Credits: City of Bayeux, DRAC Normandie, University of Caen Normandie, CNRS, Ensicaen, Photos: 2017—La Fabrique de patrimoines en Normandie)

In addition to depicting military tactics used in the Norman Conquest, the scene also provides visual evidence for eleventh-century battle gear. Cavalrymen are shown wearing conical steel helmets with a protective nose plate, mail shirts, and carrying shields and spears whereas the foot soldiers are seen carrying spears and axes. Representations of the cavalry show that the soldiers were armored but the horses were not. The brutality of war is evident in the battle scenes. Figures of mortally wounded men and horses are strewn along the tapestry’s lower zone as well as within the main central zone.

The Bayeux Tapestry provides an excellent example of Anglo-Norman art. It serves as a medieval artifact that operates as art, chronicle, political propaganda, and visual evidence of eleventh-century mundane objects, all at a monumental scale. This astounding work continues to fascinate.