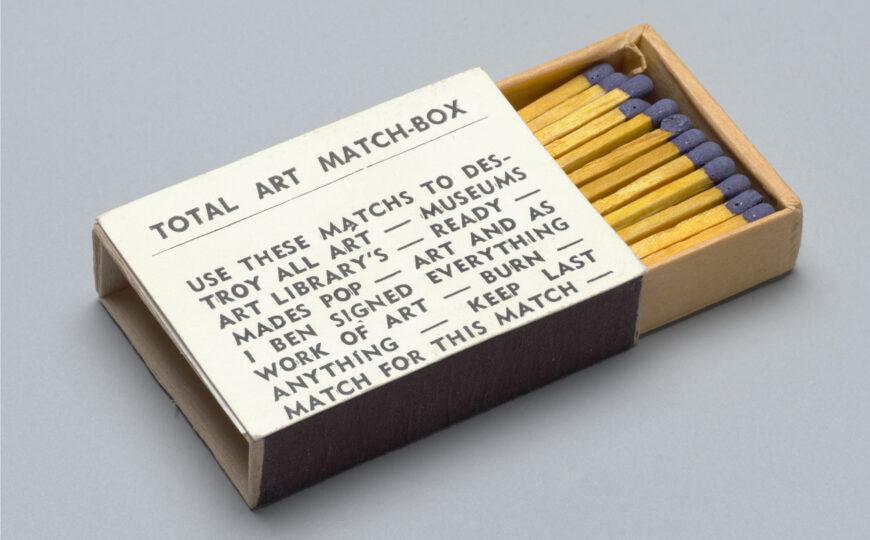

Ben Vautier, Total Art Match-Box, c. 1965, matchbox and matches, with offset label, 3.8 x 5.2 x 1.3 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Ben Vautier

Please wash your face. Make a salad. Scream! Exit. These are some performance instructions and activities that counted as art within Fluxus, an international artist collective active in the United States, Western Europe, and Japan beginning in the 1960s. Fluxus artists presented everyday actions reframed as performance art and assembled found objects into game-like kits, which they sold at affordable prices. Fundamentally anti-elitist, Fluxus artists found value in the everyday. They believed art can be anywhere, belong to anyone, and that anyone can make it.

George Maciunas, Fluxus Manifesto, 1963, offset lithograph, 20.9 x 14.7 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © George Maciunas

Fluxus ideas are encapsulated in a 1963 manifesto composed by leading organizer and publisher George Maciunas, which demands that we “purge” the world of “professional & commercialized culture” and, instead, “promote non art reality to be grasped by all peoples.” [1] Maciunas originally referred to Fluxus as Neo-Dada in homage to the early 20th-century Dada movement. According to his own brand of socialist politics, Maciunas believed the Fluxus approach to creativity could eventually make high art obsolete by infusing art into everyday life. In a related work, Ben Vautier’s modest Total Art Match-box instructs us to use the enclosed matches to destroy all art. Such provocations entail a mix of humor and danger as they direct the viewer to carry out specific actions, or at least to seriously imagine them. In the Fluxus worldview, art is no longer defined by unique, precious objects made by virtuosic, individual creators. Rather, art becomes a matter of one’s perception of day-to-day reality.

Performing the everyday

Among the earliest documents of Fluxus activities is a German TV news report on a Fluxus festival held at the Museum Wiesbaden, Germany, in September 1962. This month-long festival launched a European Fluxus tour that traveled to Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Paris, Düsseldorf, Stockholm, Oslo, and Nice. The news report shows how German audiences responded to Fluxus’s radically new definition of art—reactions ranged from delight and surprise to confusion, disgust, and boredom. The news report features several performances.

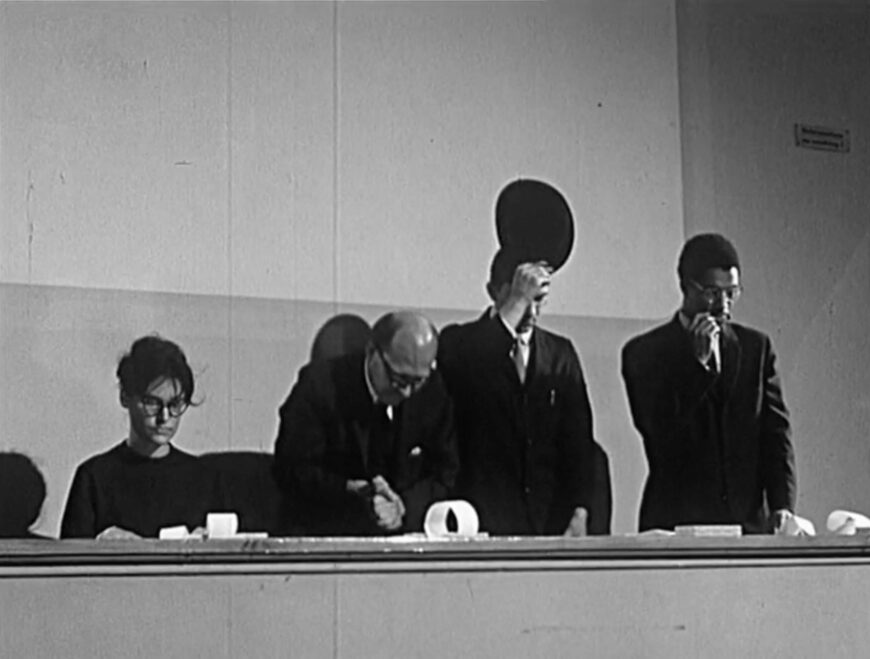

Still from digitized German TV news report on a Fluxus festival held at the Museum Wiesbaden, Germany, in September 1962. George Maciunas, Dick Higgins, Nam June Paik, Alison Knowles, Emmett Williams, George Maciunas, Benjamin Patterson performing in George Maciunas, In Memoriam to Adriano Olivetti, performed at the Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik, Städtisches Museum, Wiesbaden, September 8, 1962 (watch the film here: The Scores Project, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles) © Hessischer Rundfunk

In Maciunas’s In Memoriam to Adriano Olivetti, shown in the image above, the performers referred to numbers on scraps of adding machine paper as cues for actions such as lifting a hat, sitting and standing, pointing, stomping, and making percussive sounds with simple objects or their bare hands.

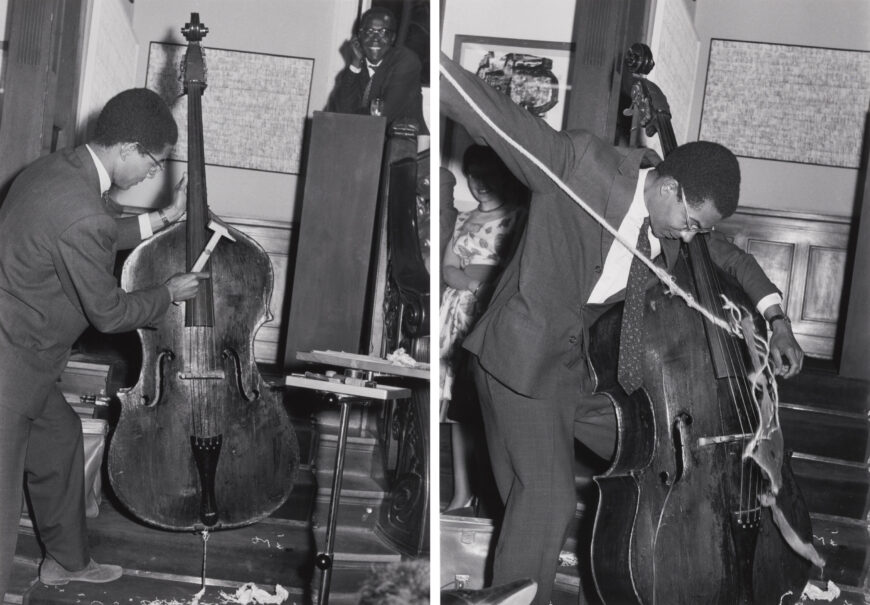

Benjamin Patterson, Variations for Double-Bass, performed during Kleines Sommerfest: Après John Cage, Galerie Parnass, Wuppertal, West Germany, June 9, 1962, gelatin silver print, 33 x 22.8 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Ben Patterson

In Benjamin Patterson’s performance of his Variations for Double-Bass, the classically trained musician used clothespins, a nylon stocking, an air pump, and paper to make unexpected sounds with his instrument. His 1960 performance work Paper Piece, also featured on the tour, explored the sonic, visual, and material qualities of paper while being inherently participatory, as rolls of paper were typically unfurled into the audience.

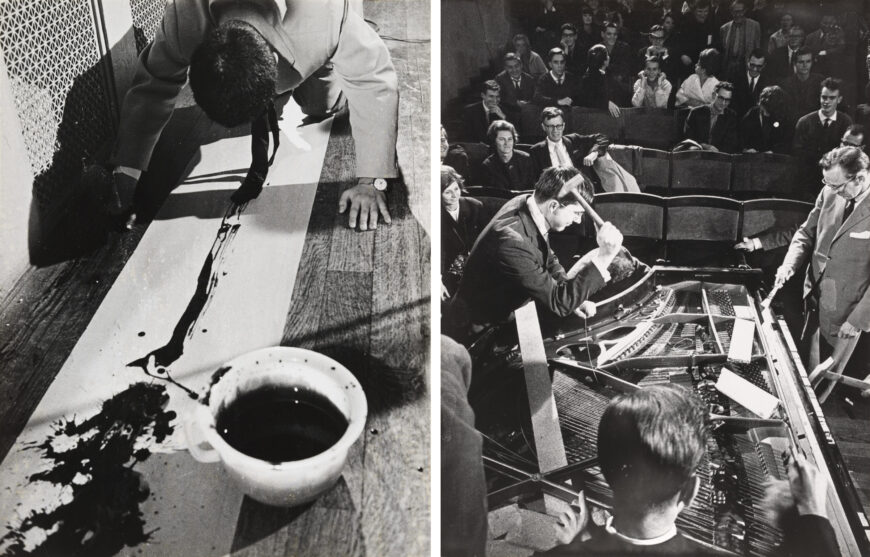

Performances at the Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik, Städtisches Museum, Wiesbaden, September 1–23, 1962. Left: La Monte Young, Composition 1960 #10 (to Bob Morris), performed by Nam June Paik; right: Philip Corner, Piano Activities, 1962, performed by various artists in attendance, gelatin silver prints, 20.8 x 16.1 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

In the German TV report, we see another performer using paper in an unexpected way. Nam June Paik’s expressive interpretation of La Monte Young’s instruction to “Draw a straight line and follow it” involved painting (with a mixture of ink and tomato juice) a line with his head, hands, and necktie. The final piece depicted in the film is a cacophonous realization of Philip Corner’s Piano Activities, in which the performers playfully attacked a piano with various objects and then carted it offstage to the hoots and hollers of the audience. Other concerts ended with George Brecht’s Word Event, which instructed, simply, “Exit.”

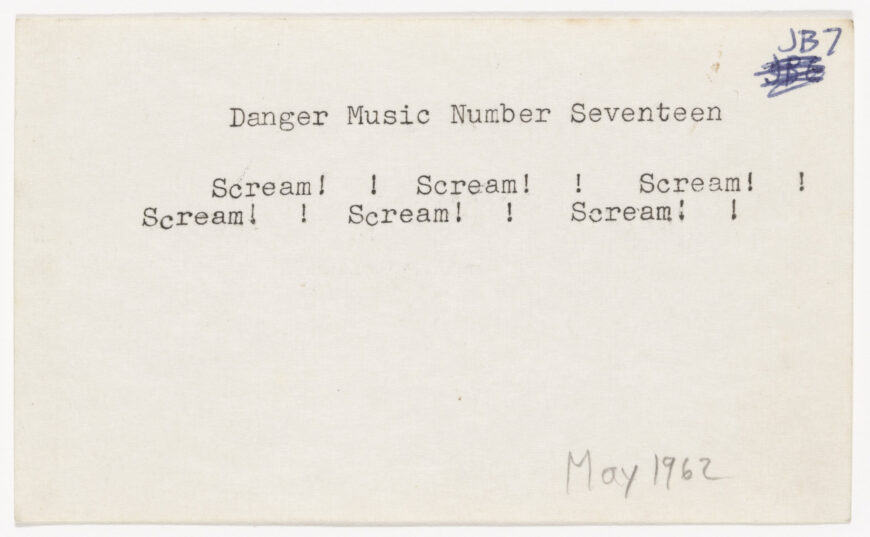

Dick Higgins, Danger Music Number Seventeen, 1962, mimeograph and ballpoint pen on cardstock, 7.5 x 12.7 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Dick Higgins

Event scores and multiples

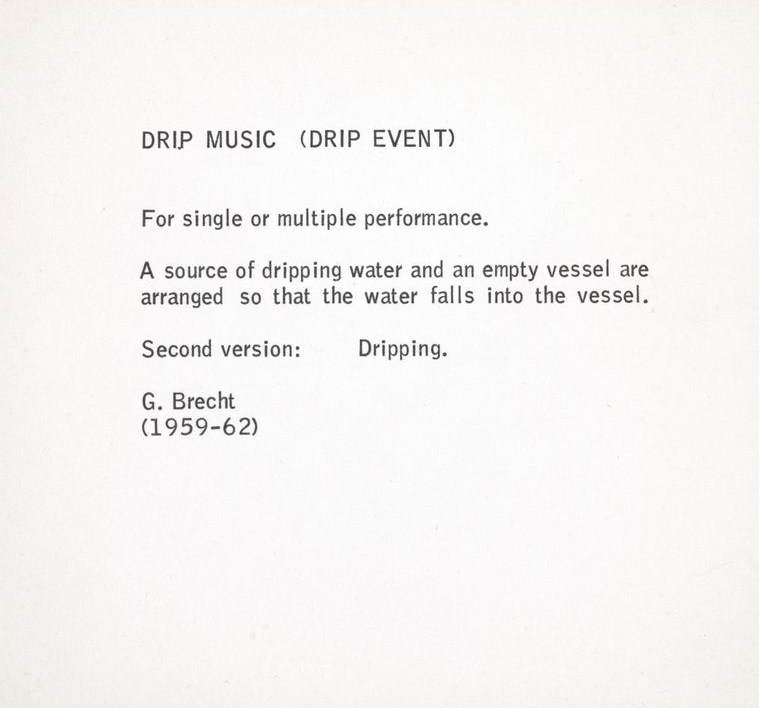

A commonly used format among Fluxus artists were text-based performance instructions they called event scores. Some of the briefest instructions include “Please wash your face” (Benjamin Patterson), “Make a salad” (Alison Knowles), “Scream!” (Dick Higgins), and “Exit” (George Brecht). The interpretation of event scores such as Brecht’s Drip Music (Drip Event)—“A source of dripping water and an empty vessel are arranged so that the water falls into the vessel”—changed from concert to concert, and there were even sculptural realizations of such pieces. Artists’ turn to the score format was inspired by 1950s innovations in musical notation by New York School composers including Morton Feldman, Earle Brown, and John Cage, with whom many Fluxus artists studied.

George Brecht, Drip Music (Drip Event), 1959–62, offset print (Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Jean Brown Papers, 890164, box 127) © George Brecht

Scores were a useful format for artists because they were easy to distribute and created opportunities for collective and collaborative production—allowing the artwork to appear in different times and places and with different performers and audiences. Scores instigate processes with indeterminate outcomes; although we do not know what the final result of an action will be, we are invited to appreciate whatever happens. As Brecht once said, “No catastrophes are possible.” [2]

Various artists, Fluxkit, 1965–66, vinyl-covered attaché case, containing objects in various media, 32.5 x 44 x 12 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Estate of Shigeko Kubota

Fluxus artists also designed, produced, and circulated interactive, game-like kits called multiples that allowed viewers to directly experience Fluxus ideas. Primarily designed and assembled by Maciunas after his friends’ proposals, Fluxus multiples were meant to be sold inexpensively by mail-order. These cleverly designed works are characterized by a comedic or conceptually provocative relationship between the label and its contents, such as Shigeko Kubota’s Flux Medicine, which contains empty pill capsules, or Ken Friedman’s A Flux Corsage, which contains loose seeds.

Ken Friedman, A Flux Corsage, 1969, plastic box with offset label, containing seeds, 12 x 10 x 1.3 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Ken Friedman

Intermedia

It was fitting that the first Fluxus festival took place in the concert hall of an art museum, given the artists’ play with both visual and musical elements. Many of the artists involved were trained as painters or musicians but were interested in working between established mediums (such as sculpture, sound, or language) and disciplines (such as visual art, music, or poetry), a phenomenon named “intermedia” (meaning “between media”) by Dick Higgins in 1965. The intermedia concept opposed modernist ideas of the time, which prioritized the separation of mediums and disciplines in favor of the purity and specificity of specialized artistic pursuits. According to a strict definition of modernism, for example, only painters should make paintings, and painters should only make paintings. In contrast, Fluxus artists, who thought of themselves as aesthetic misfits in pursuit of non-professional creativity, incorporated everyday life into their work, devised action-poems or book-objects, and employed other hybrid intermedia formats that blended different artistic mediums.

Dick Higgins, Invocation of Canyons and Boulders, 1965, plastic box with offset labels, containing film loops, 12 x 10 x 2.6 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York) © Dick Higgins

Another aspect of Fluxus intermedia is the artists’ approach to authorship, production, and distribution of their work, which mimics how artworks are created in theater, literature, and architecture. In those fields, creation is collaborative, and the finished work exists in multiple copies; the author hands off the interpretation and production of their work to others. Fluxus artists’ search for alternative models of art’s production and distribution was fundamentally rooted in a creative reconceptualization of music. They defined music as a group of people being together, experimenting with a given set of rules, making sounds or not, but most importantly listening and paying very careful attention to one another and to the world.

The eternal network

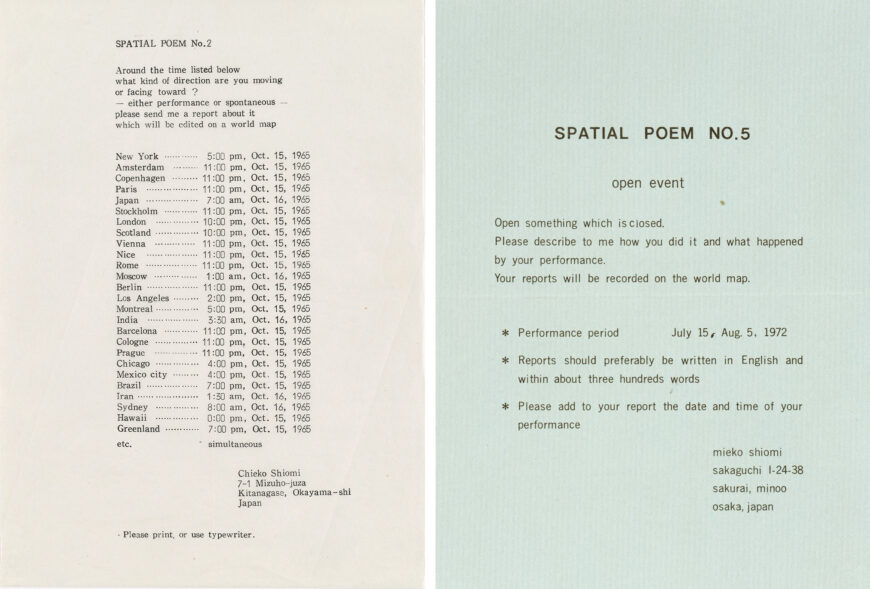

Fluxus artists frequently used the postal service to distribute their works, setting a precedent for the proliferation of mail art in later decades. Japanese Fluxus artist Mieko Shiomi’s Spatial Poem is a prime example. Between 1965 and 1975, Shiomi sent out instructions to her global network and then collected, documented, and recirculated the responses while continuing to meet her obligations as a stay-at-home caregiver. She reflected, “It was frustrating to be physically restrained to one place at a time. I felt that art should be alive everywhere all the time, and at any time anybody wanted it.” [3] French artist Robert Filliou considered Fluxus to be part of an “eternal network” of artists who were conceptually close despite being separated by vast physical distances. Fluxus artists would go from performing their touring concert program to establishing artists’ housing in Soho and, at least in the case of Maciunas, planning (unrealized) communes in Massachusetts, Japan, and the Caribbean.

Left: Mieko Shiomi, Score for Spatial Poem No. 2 (Direction Event), 1965 (Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Jean Brown Papers, 890164, box 47, folder 3); right: Mieko Shiomi, Spatial Poem No. 5/open event, 1972 (Walker Art Center, Minneapolis) © Mieko Shiomi

Legacy and influence

Around the same time as Pop and Minimalism, Fluxus pursued alternative aesthetic experiences to mass-market consumer culture. These artists helped develop many approaches to art-making that we associate with contemporary art today, such as conceptualism, performance art, participation, and new media. In hindsight, we can also recognize Fluxus as among the most diverse avant-garde movements of its moment, including in its ranks artists who were women, East Asian, African American, and/or queer. Some would argue that Fluxus is still active today. It may indeed be, since the point of Fluxus is that you can do these pieces too. Please wash your face. Make a salad. Scream! Exit.