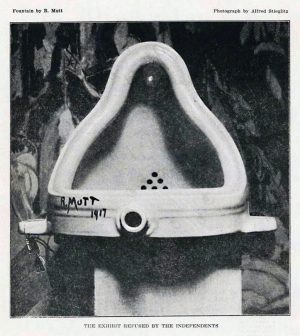

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (original), photographed by Alfred Stieglitz in 1917 after its rejection by the Society of Independent Artists

Art as provocation

When you look at Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, a factory-produced urinal he submitted as a sculpture to the 1917 exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York, you might wonder just why this work of art has such a prominent place in art history books.

You would not be alone in asking this question. In fact, from the moment Duchamp purchased the urinal, flipped it on its side, signed it with a pseudonym (the false name of R. Mutt), and attempted to display it as art, the piece has generated controversy. This was the artist’s intention all along—to puzzle, amuse, and provoke his viewers.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (reproduction), 1917/1964, glazed ceramic with black paint (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Fountain was submitted to the Society of Independent Artists, one of the first venues for experimental art in the United States. It is a new form of art Duchamp called the “readymade”— a mass-produced or found object that the artist transformed into art by the operation of selection and naming. The readymades challenged the very idea of artistic production, and what constitutes art in a gallery or museum. Duchamp provoked his viewers—testing the the exhibition organizers’ liberal claim to accept all works with “no judge, no prize” without the conservative bias that made it difficult to exhibit modern art in most museums and galleries. Duchamp’s Fountain did more than test the validity of this claim: it prompted questions about what we mean by art altogether—and who gets to decide what art is.

A world of questions

Duchamp’s provocation characterized not only his art, but also the short-lived, enigmatic, and incredibly diverse transnational group of artists who constituted a movement known as Dada. These artists were so diverse that they could hardly be called a coherent group, and they themselves rejected the whole idea of an art movement. Instead, they proclaimed themselves an anti-movement in various journals, manifestos, poems, performances, and what would come to be known as artistic “gestures” such as Duchamp’s submission of Fountain.

Dada artists worked in a wide range of media, frequently using irreverent humor and wordplay to examine relationships between art and language and voice opposition to outdated and destructive social customs. Although it was a fleeting phenomenon, lasting only from about 1914-1918 (and coinciding with WWI), Dada succeeded in irrevocably changing the way we view art, opening it up to a variety of experimental media, themes, and practices that still inform art today. Duchamp’s idea of the readymade has been one of the most important legacies of Dada.

Dada readymades

In a 1936 essay titled “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” the German philosopher and cultural theorist, Walter Benjamin, proclaimed that the industrial age had changed everything about the way we view art. He believed that new technologies for mass production and media (such as photography) would invalidate the remnants of classical artistic traditions that were still being promoted by institutions such as art academies and museums.

Marcel Duchamp, left: Bicycle Wheel, original 1913, reproduction 1964, wheel and painted wood, 64.8 x 59.7 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art) (photo: Stefan Powell, CC BY 2.0); right: Bottle Rack, original 1914, reproduction 1963/1976, galvanized iron, 57 x 36.5 x 36.5 cm (Moderna Museet, Stockholm) (photo: Hans Olofsson, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Duchamp’s idea of the readymade, which he began exploring with works such as Bicycle Wheel and Bottle Rack as early as 1913, confronted these issues head on—subjecting the idea of art to intense scrutiny.

Pablo Picasso, Still Life with Chair Caning, 1912, oil and oilcloth on canvas framed with rope, 29 x 37 cm (Musée Picasso, Paris)

Although Duchamp coined the term “readymade” and was the first to show mass produced objects as art, he drew inspiration from Braque, Picasso, and the other Cubists then working in Paris, who had already begun incorporating everyday items from mass culture (such as newspaper and wallpaper) into their abstracted collages.

International collaboration

Sharing and adapting characterized the key approaches of Dada artists, and Duchamp’s use of articles from everyday life caught on among the various Dada collectives, though each used the readymade in ways that reflected their own group’s specific artistic concerns.

Art historian Leah Dickerman has demonstrated that Dada can best be understood by looking at its distinct manifestations in six urban centers. The Dada movement officially began in Zurich, a city in politically neutral Switzerland where many artists and intellectuals fled during World War I. From there, the movement radiated outward to the other groups in Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, and Paris—each of which had members in communication with the other groups.

Zurich Dada

Beginning in 1916, Zurich Dada centered around the Cabaret Voltaire, which provided a creative haven for exiled artists and others to explore new media and performance while critiquing what they saw as the predominant “rational” culture that led to the irrational horrors of the war. Members of this group included Hugo Ball (German), Emmy Hennings (German), Hans (also known as Jean) Arp (from Alsace, a contested territory between France and Germany), Sophie Taeuber (later to become Sophie Taeuber Arp, Swiss), and Tristan Tzara (Romanian). It was their raucous, irreverent, and absurd performances ranging from sound poetry to dances in costumes modeled after Native American and other non-European ritual garments, that gained the attention of the avant-garde art world. In addition to their collaborative art practices, exhibitions, and performances, the artists in Zurich published a journal and other graphic materials to spread their ideas.

Taeuber and Arp

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Tête Dada (Dada Head), 1920, wood and paint, 29.43 cm high (Centre Pompidou, Paris)

Sophie Taeuber produced an incredible collection of marionettes and worked in media such as textiles and wood, which had traditionally been relegated to the category of “craft” (ostensibly a “low” art associated with “women’s work”) by European academic art institutions. Hans/Jean Arp moved away from his previous interest in German Expressionism to develop what he called “chance collages,” in which it is said that he tossed torn or cut paper squares onto a larger sheet of paper on the floor and then glued them in whatever formation they landed. Taeuber and Arp also produced abstract wooden sculptures, many of which resembled organic forms or, alternatively, mechanical forms such as mannequin heads.

In works such as these, Zurich Dada demonstrated a skeptical attitude toward rationality and intention, found strategies to explore abstraction, and displaced the artist’s hand (that is, the direct connection to the work of art that was the basis of the “aura” that Benjamin associated with traditional artworks in museums and galleries). Instead of the specialized materials of fine art such as oil paint and marble, these artists favored mass media imagery and everyday commercial materials such as paper. They sought to integrate art and life more closely in order to critique the effects that modern industrialization—factory labor, mass production, and rapid urbanization—had wrought on society. These industrial advances raised the standard of living for many, but had a devastating impact on the battlefield where millions died due to poison gas and other types of newly efficient weapons.

Berlin Dada

Dada arrived in Germany in 1917 when Richard Huelsenbeck, a German poet who had spent time at the Café Voltaire, brought the ideas he encountered in Zurich to Berlin. Here, Dada became even more overtly political. Using the readymade, new photographic technologies, and elements from everyday life, including mass media imagery, Huelsenbeck and his collaborators critiqued modern bourgeois society and the politics that had led to the First World War.

Berlin Dadaists embraced the tension and images of violence that characterized Germany during and after the war, using absurdity to draw attention to the physical, psychological, and social trauma it produced. Employing strategies ranging from a Cubo-Futurist rendering of form to mixed-media assemblage, they satirized the immorality and corruption of the social elite, including cultural institutions such as museums. Many of these works were featured alongside manifestoes and other textual works in Dada journals.

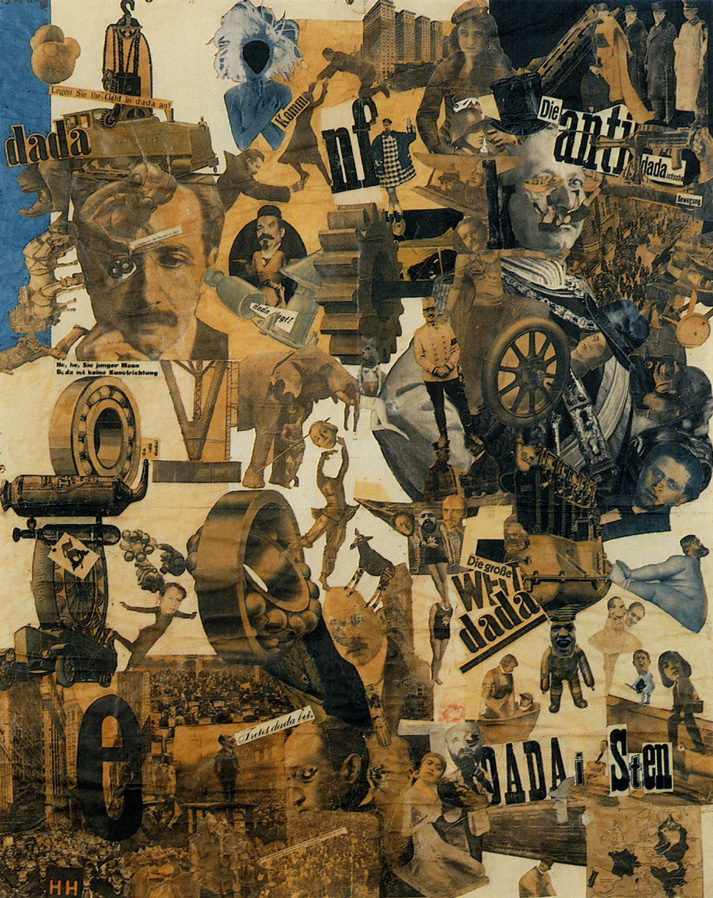

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919-1920, photomontage and collage with watercolor, 114 x 90 cm (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie)

During the Weimar Republic, artists such as Hannah Höch produced collages using imagery from magazines and other mass media to provoke the viewer to critically evaluate and challenge cultural norms.

One of the most transformative Berlin Dada practices—one that continues to inform contemporary art today—was the invention of mixed media installations. This began in earnest with the First International Dada Fair in 1920, which featured an assortment of paintings, posters, photographs, readymades, and two- and three-dimensional mixed media art.

First International Dada Fair, Galerie Otto Burchard, Berlin, 1920 (Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin)

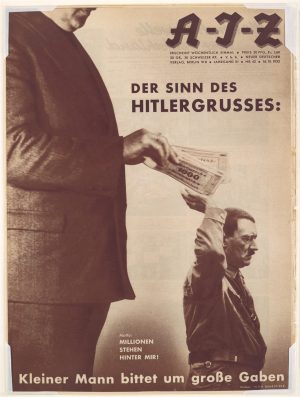

John Heartfield, Der Sinn des Hitlergrusses: Kleiner Mann bittet um grosse Gaben (The Meaning of the Hitler Salute: Little Man Asks for Big Gifts), 1932 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In Berlin, artists such as John Heartfield and George Grosz, political agitators who had anglicized their names in protest of overzealous German nationalism, continued their Dada cultural interrogations into the 1930s to combat the rise of the National Socialist (Nazi) Party. Because Heartfield, Grosz, and other artists involved in Berlin Dada embraced Communism as the solution to fight fascism, they combined Dada strategies with the radical agitprop (agitational propaganda) that had been used to mobilize public opinion against traditional bourgeois society during the Russian Revolution and the establishment of the Soviet Union. Heartfield is best known for his use of photomontage. In the hands of Heartfield and other Dadaists, mainstream advertising, high society publicity, and fascist propaganda was turned on its head, providing readers with humorous, yet sobering exposés.

Hannover Dada

Although a spirit of collaboration characterized Dada in all its manifestations, Hannover Dada is best known for the collages and three-dimensional assemblages of one artist: Kurt Schwitters. Labeling his art “Merz” (a term he extracted from the word Kommerz, German for “commerce”), his art reflected a desire to explore the connections between human experience, memory, and objects in the world—particularly discarded scraps of newspaper, movie tickets, or other scrapped consumer goods. Schwitters gave these cast-off everyday objects new life in his collages that retained a dialogue with painting, formal abstraction, and sculpture.

This approach is particularly visible in his Merzbau, a project that he worked on for years in his Hannover home before having to abandon it for subsequent efforts in Norway and England when he was forced by the Nazis to flee Germany. Within this cottage-sized three-dimensional assemblage he incorporated abstract structures reminiscent of German Expressionist film and stage design along with objects that served as souvenirs of key moments and relationships, expressing also his interest in material, physical, and spiritual interactions.

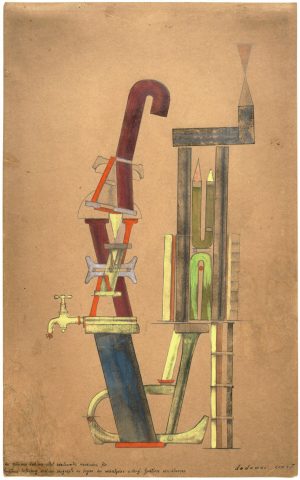

Max Ernst, Little Machine Constructed by Minimax Dadamax in Person, 1919-20, handprinting, pencil and ink frottage, watercolor, and gouache on heavy brown pulp paper, 49.4 x 31.5 cm (Guggenheim)

Cologne Dada

Dada in Cologne (a city in western Germany) is most closely associated with the diverse artworks of Max Ernst, an artist who produced a prolific body of work that included frotage (rubbings), painting, collage, and mixed media assemblage. These works, many of which explored the absurd and suggested fantastic creatures, dwellings, and landscapes, are often associated with Surrealism, a movement with which he was also affiliated. Because Ernst worked in Germany and France, fled to the United States during World War II, and later returned to Europe, his work impacted art on both sides of the Atlantic and can be found in collections around the world.

New York and Paris Dada

New York Dada, where we began this discussion, lost its momentum when its two primary leaders, Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia, returned to Europe after World War I. In Paris, the two leaders joined like-minded artists and former exiles to continue their raucous, yet playful, interrogation of art and culture. More attuned to the approaches of the Zurich and New York groups, Paris Dada centered around spectacle and was less overtly political than Dada in Germany. The group’s performances, photographs, mixed media collage, and installations nevertheless emphasized the absurd and challenged social norms. These interests, combined with the emerging appeal of investigating imagery that reflects psychological states, led many of the Paris Dada group (including Man Ray, best known for his experimental photographs) to join the Surrealists who, led by writer Andre Breton, made Paris the center of their activities.

Dada and Its Legacies

Many of the artists who identified with Dada went on to become Surrealists. Because of this, and the relatively brief duration of the Dada phenomenon, it took some time for subsequent artists and historians to appreciate its value. In retrospect, however, we can see the reverberations of Dada throughout the twentieth century, and it has been one of the main contributors to contemporary art practices since its revival as Neo-Dada in the 1960s.

Additional resources:

World War I and Dada from The Museum of Modern Art

John Heartfield, Der Sinn des Hitlergrüsses at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Marcel Duchamp on The Museum of Modern Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Leah Dickerman and Brigid Doherty, Dada: Zurich, Berlin, Hannover, Cologne, New York, Paris (Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2005)