Art, Pride, and the Rainbow Flag: Curators and educators at the Getty share strategies for uncovering queer and trans histories from antiquity to the present.

Read Now >Chapter 3

An Art History of Gender Identity and Sexuality

Queer and Trans Visibility in Art History Saves Lives

Do you see yourself in history?

Do you see people who look like you or who identify as you do in these contexts? If so, when or where? What are their circumstances or aspirations? Are they named or nameless? For many members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual, two-spirit, and a range of additional expressions of gender identity and sexuality (abbreviated as LGBTQIA2+), often we do not see ourselves reflected or respected in the past. Around the world today we face continued prejudice and persecution. These factors can make it hard to imagine we have a future. Queer and trans visibility in art history and museums saves lives.

Kent Monkman, Metis, Fisher River Band, History is Painted by the Victors, 2013, acrylic paint on canvas, 182.88 x 287.65 cm (Denver Art Museum)

Contemporary artists can be advocates for inclusion and change. They often draw inspiration from art(ists) of the past in order to present a vision for the future. One example is Kent Monkman, who is Cree and Scottish and identifies as two-spirit, a term used by some Indigenous folx to describe individuals who embody both masculine and feminine spirits and thus move beyond a gender binary. His work engages with long-standing European and North American histories of art by remixing historic compositions and incorporating Native peoples as protagonists. He also critiques legacies of colonialism, racism, homo/transphobia in the art world more broadly and museums in particular. For example, his large painting History is Painted by the Victors presents a poignant continuum of queer and trans history.

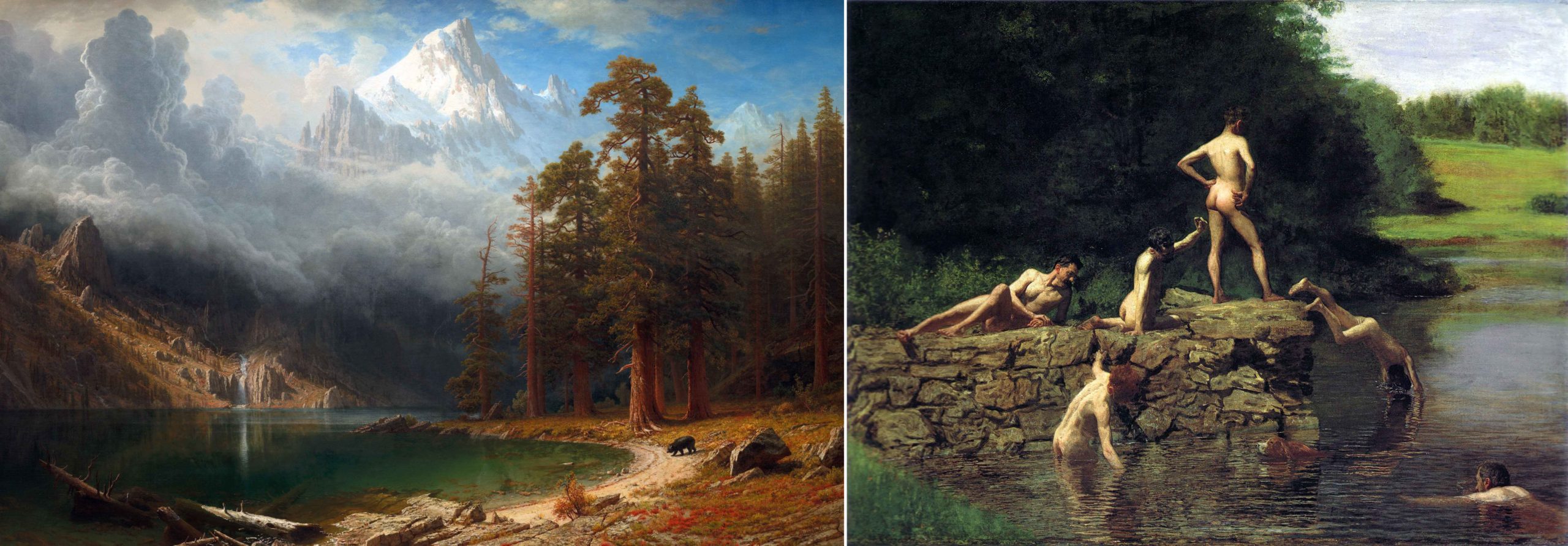

Left: Albert Bierstadt, Mount Corcoran, c. 1876–77, oil on canvas 154.1 x 243.5 cm (National Gallery of Art); right: Thomas Eakins, Swimming, 1885, oil on canvas, 27 3/8 x 36 3/8 in. (Amon Carter Museum)

In Monkman’s painting, visual references to iconic of late 19th-century American art history abound: These include panoramic vistas by government-sponsored painter Alfred Bierdstadt, who documented the beauty of landscapes (the ancestral and current homes of countless Native communities) that would eventually be regulated by US state and federal laws, as well as scenes of white, settler, male intimacy outdoors by realist artist Thomas Eakins, known for homoerotic subtexts in his works. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle—Monkman’s alter ego—gazes directly at the viewer from the lower center of the canvas while painting an image of Crazy Horse and Northern Plains tribes defeating Lt. Colonel George Custer’s troops at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876.

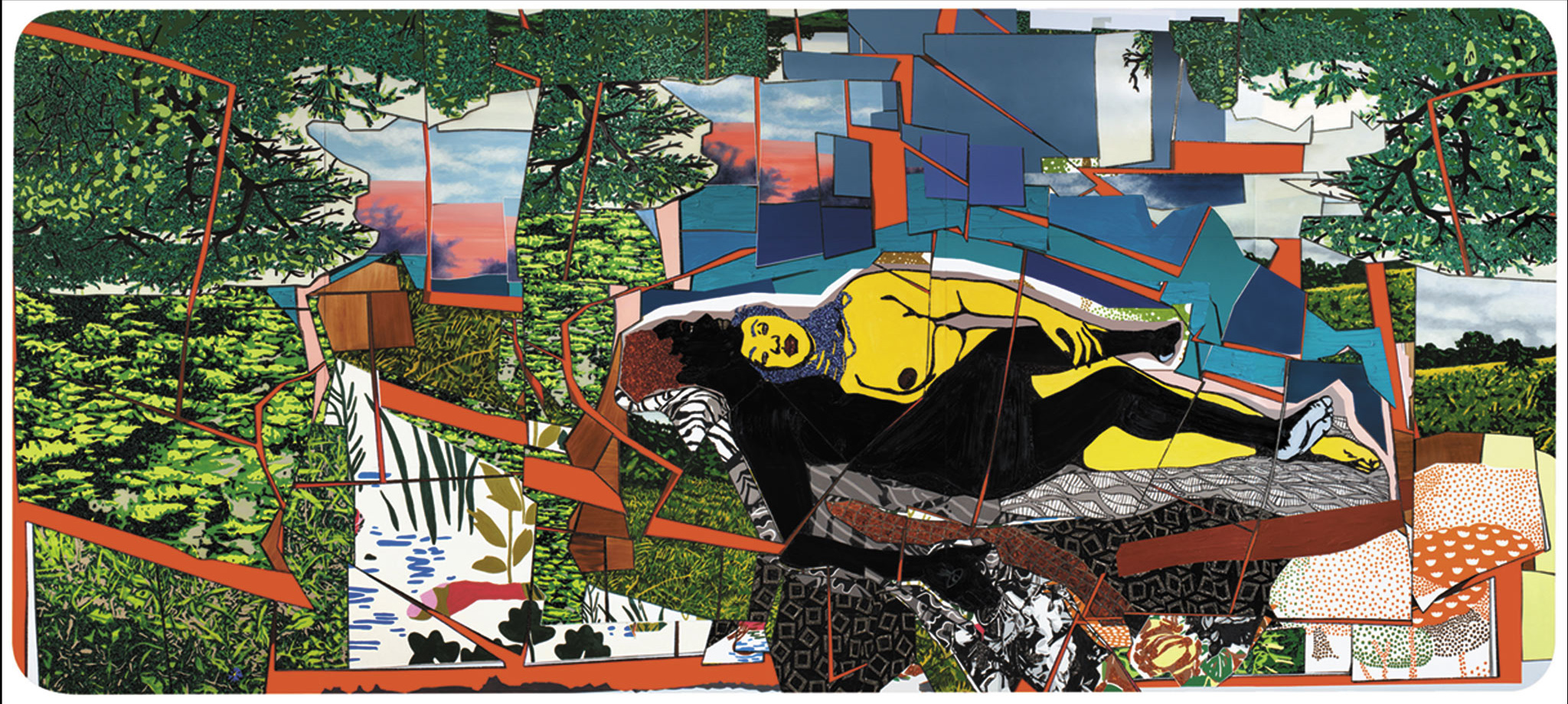

Mickalene Thomas, Sleep: Deus femmes noires, 2012, rhinestones, acrylic, enamel on wood © 2012 by Mickalene Thomas

One advantage of turning to contemporary art is that artists today—especially creators of color—are revealing vibrant and long histories of queer and trans presence that have otherwise been marginalized, censored, or erased. Mickalene Thomas, for example, reimagines nineteenth-century French painter Gustave Courbet’s canvas of two white women sleeping as an intimate scene between Black women.

Gustave Courbet, The Sleepers, 1866, oil on canvas, 135 x 200 cm (Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux Arts de la ville de Paris; photo: gmpgoh, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

By doing so, she challenges ideas about bodies and beauty, and aims to make headway into the “boy’s club” of individuals often championed in the art world. Thomas and Monkman both help us see the past anew and their work asks that we take a moment to unlearn harmful histories of hetero- and cis(gender)-normativity that have relegated the rainbow of LGBTQIA2+ and other historical identities to the shadows.

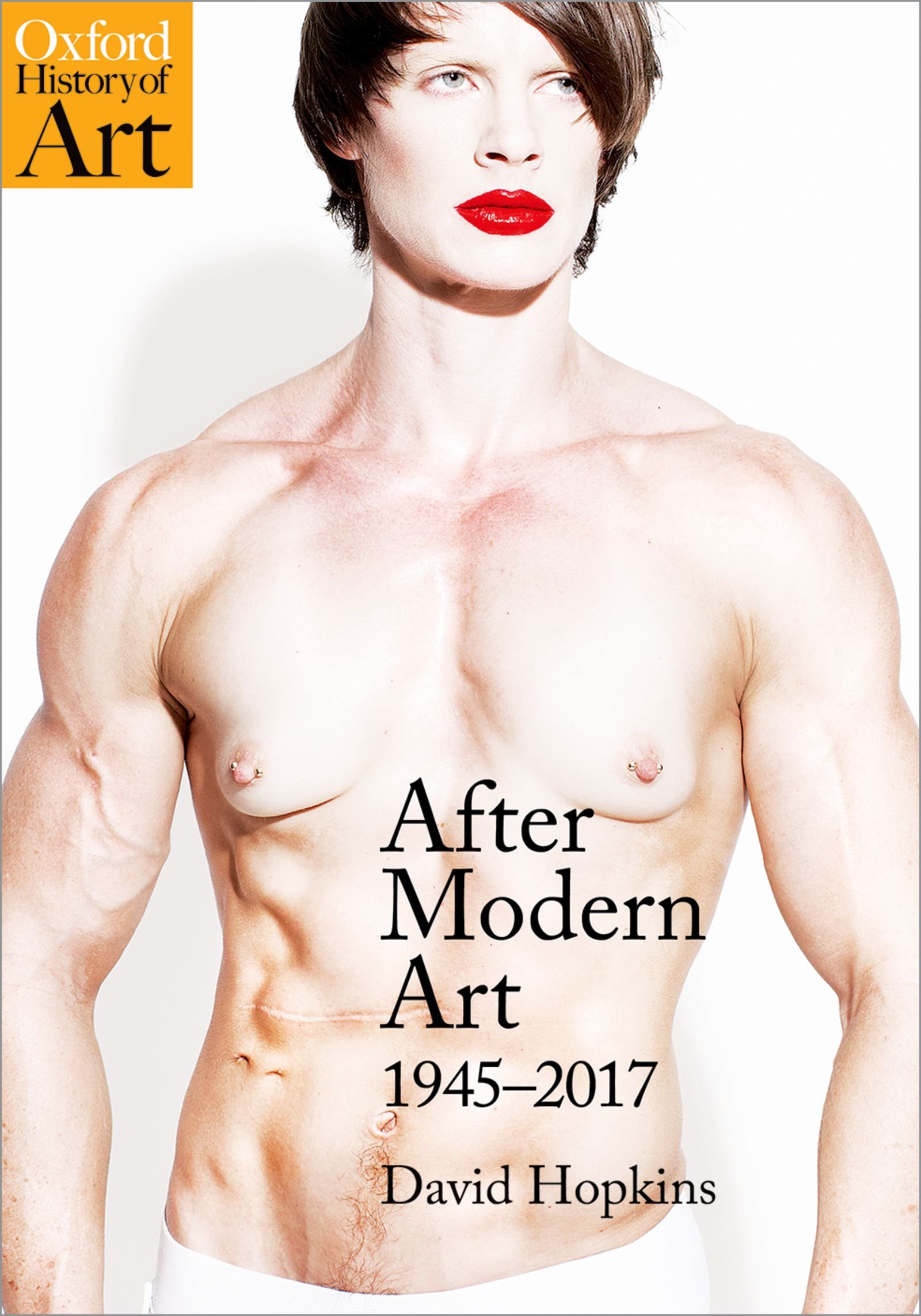

Performance artist Cassils on the cover of David Hopkins, After Modern Art: 1945–2017, Oxford University Press, 2018

One common misconception is that queer and trans history is fairly short or recent, limited to the last half-century in some cases or with a few early milestones in the late 1800s. Certainly the word “homosexual” (and by correlation “heterosexual”) was coined in the 1860s in Austria, and the Pride movements for gay, lesbian, and transgender rights were ignited in the 1960s in the United States, with the first march in 1970. And it is only recently that LGBTQIA2+ subjects and artists are slowly making their way into art history surveys, including the appearance of performance artist Cassils on the cover of Oxford’s After Modern Art: 1945–2017 volume. But our histories can be traced far back in deep time—to the origins of human creative output—and across the planet, if we know where to look. This chapter will introduce a range of historical case studies that hope to expand our ideas about historic gender and sexuality.

Read essays about approaches to LGBTQIA2+ art history

Identity Politics: From the Margins to the Mainstream: From about 1950 to the present, art historians have endeavored to tell diverse stories, including those of queer individuals.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Queering Art History: Breaking from Western-centered Narratives

Papahou (Treasure Box), Maori, 1700/1800, wood, shell, green stone (© Trustees of The British Museum)

Global art history from the paleolithic period to the present reveals kaleidoscopic ideas about human relationships and intimacy. Archaeology and anthropology are leading the way by introducing us to intersex and non-binary people, known now through DNA analysis and items found in burials. Indigenous communities and people in the global South (those south of the Equator, including communities in many former European colonies) are reclaiming identities that have long been suppressed, often violently. The Maori (of Aotearoa, the ancestral land known also as New Zealand) carved wooden box above, for example, shows fourteen different scenes of bodies engaged in sensual and sexual acts, including a central scene of a face receiving a penis in their mouth while their tongue reaches out to the vagina next to it. Other figures on the various surfaces embrace or kiss. These forms of expression are too often forgotten or purposefully erased from the historical record precisely because they have been and continue to be seen beyond conservative views (at times termed “traditional” or “normal”).

Symposium Scene, red-figure kylix painted by Douris, 485–480 B.C.E., Attica (Greece), found in Vulci (Lazio, Italy) (© Trustees of The British Museum)

When I browse expensive print textbooks for art history or most museum gallery labels and websites, I see myself and others like me in the past through glimpses that are all too often marginalized, barely visible, or at risk of being essentialized in or erased from most presentations. On ancient Greek vase paintings, I sometimes see myself as a witness to the ancient Greek symposia, a gathering of men of myriad ages that might have involved acts of erotica, nakedness, and drinking (though I also recoil from their common imagery of older men molesting or preying upon younger boys).

Left: Hadrian and Antinous, marble, 130–140 C.E., found Janiculine Hill (Rome) (© Trustees of The British Museum); right: Michelangelo, The Dream of Human Life, about 1533 (London, The Courtauld Institute of Art)

Or I may see myself in the ancient Roman love story of emperor Hadrian and his paramour Antinous. In anecdotal “outings” of Renaissance and Baroque artists of the 1500 and 1600s, I am drawn to Michelangelo, who seems to have shown great affection toward the nobleman Tommaso dei Cavalieri, or to Caravaggio, who had relationships with multiple men, including Mario Minniti.

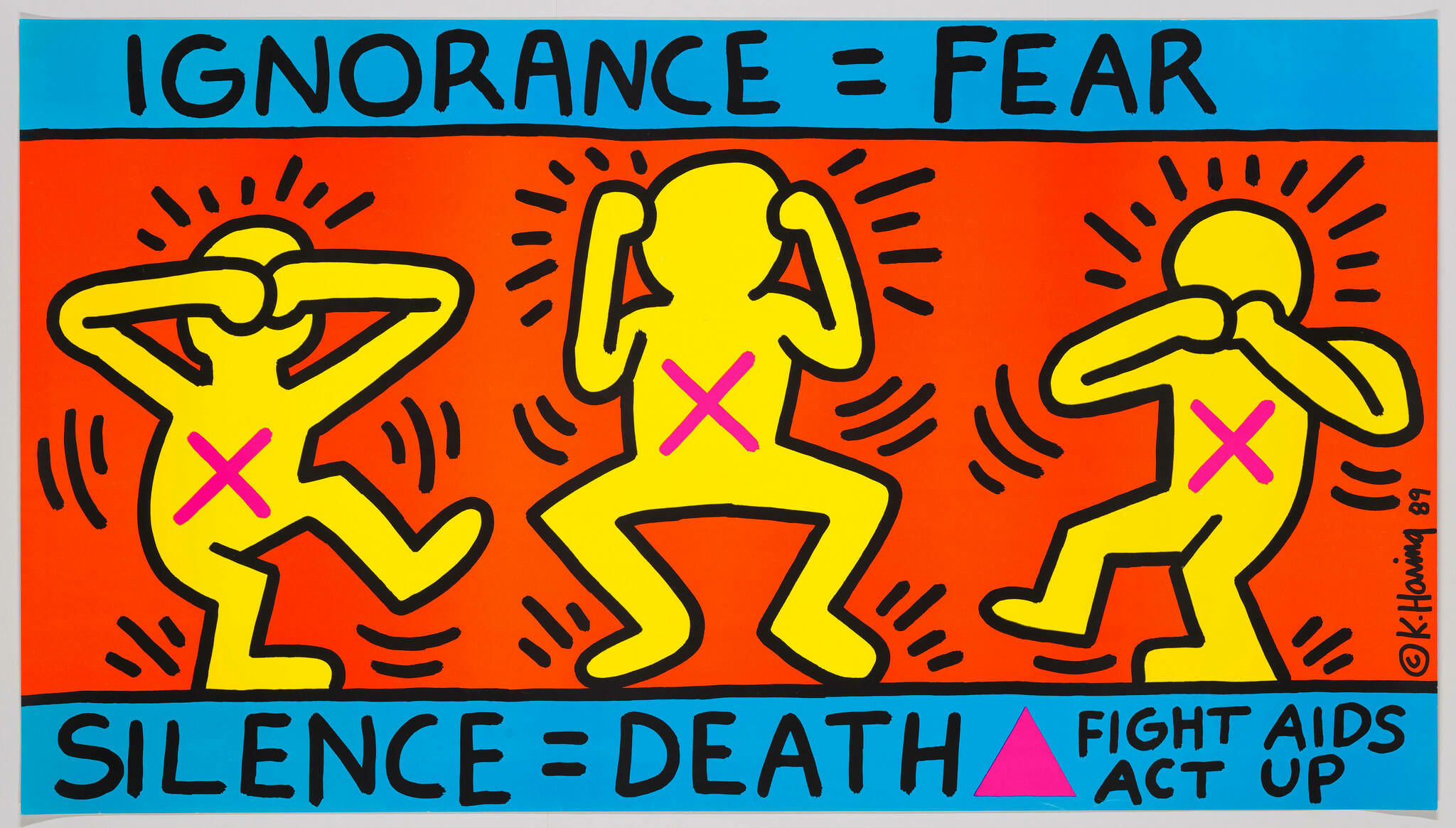

Keith Haring, Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death, 1989 (Whitney Museum of American Art)

In the modern era, I find myself in the context of art produced in Andy Warhol’s circle (through examples by Jean-Michel Basquiat or Keith Haring) against the backdrop of the AIDS pandemic.

Left: Caravaggio, The Musicians, about 1595, oil on canvas, 92.1 x 118.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art); right: Graciela Iturbide, Magnolia, Juchitán, Oaxaca, México, 1986, gelatin silver print (SFMOMA)

And on rare occasions with examples from the history of photography, I see myself as in the mirror held by Magnolia, a non-binary muxe (a third-gender category in Mexico), in a gelatin silver print by Graciela Iturbide. This snapshot constitutes the limited range of queer examples from the past that may or may not be presented in survey texts. It is worth acknowledging that most of the examples in this paragraph constitute aspects of male sexuality.

European colonialism censured forms of identity that differed from a conservative view of male-female heterosexual, monogomus relationships and gender identity as solely that assigned at birth. There is still much work to be done to uncover or reinstate instances of female, trans, and non-binary experiences, especially those of communities of color. The following resources do not all explicitly present queer and trans narratives but can serve as a starting point for such conversations.

Watch videos and read essays about topics in queer art history

The Many Meanings of the Sarpedon Krater: The all-male symposium is one lens through which to view ancient Greek vases.

Read Now >

Bronze Head from a Statue of Emperor Hadrian: The biography of this Roman emperor at times involves tales of his lover, Antionous.

Read Now >

Michelangelo, Slaves: From a queer perspective, Michelangelo’s nude male sculptures may relate to the artist’s interest in the ideal bodily forms.

Read Now >

Caravaggio, Narcissus at the Source: What are the limits of biography when viewing a potentially queer work by a premodern artist?

Read Now >

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Horn Players: Part of the artist’s style involves drawing and wordplay, which combine with themes of race (and at other times with sexuality).

Read Now >

Keith Haring, Subway Drawings: Explicit sexual and political imagery gave the artist a voice in New York’s busy subwayss.

Read Now >

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Untitled” (billboard of an empty bed): The bed is a metaphor for otherwise censured images of same-sex intimacy and the loss of life due to AIDS.

Read Now >

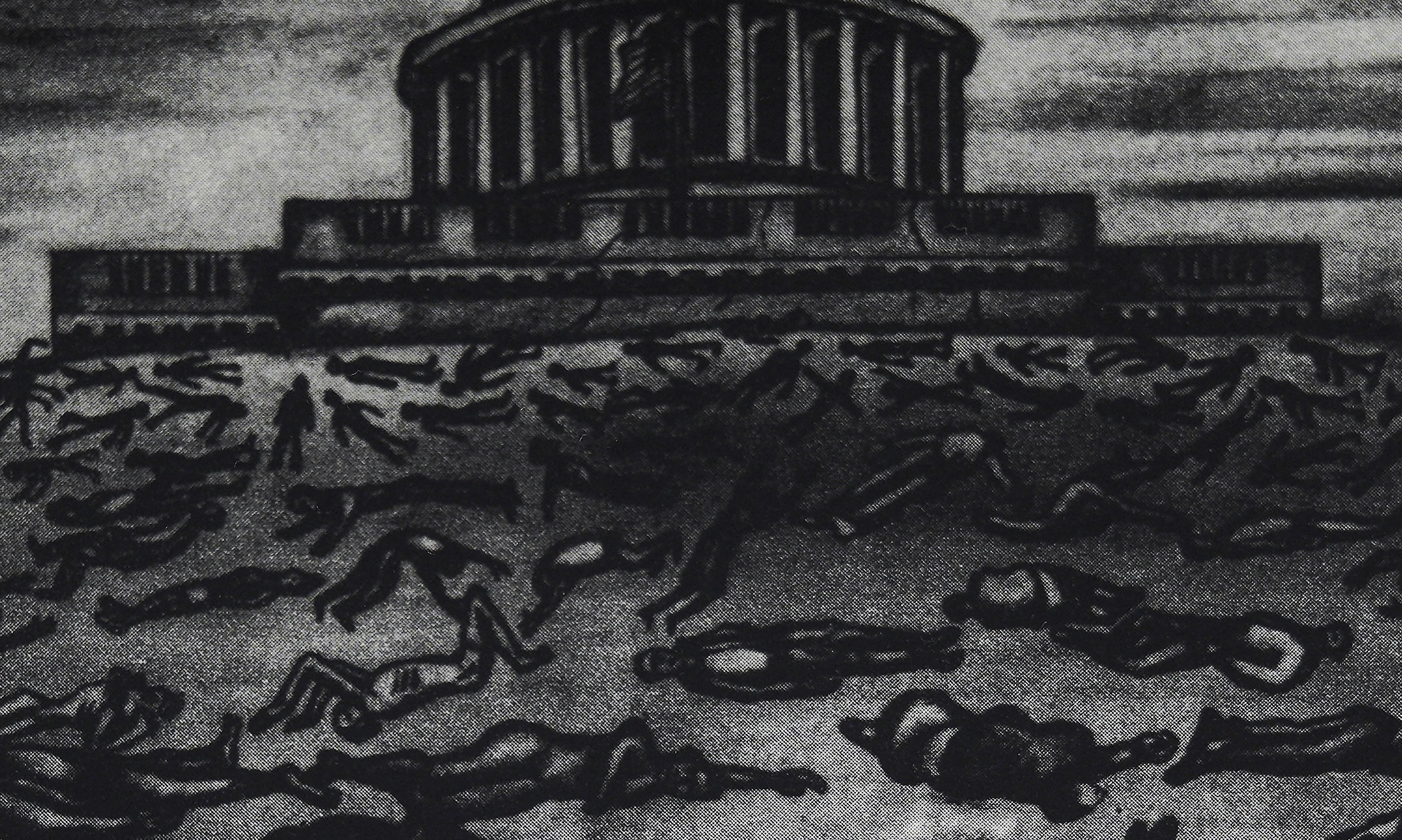

Sue Coe, Aids Won’t Wait, The Enemy is Here Not in Kuwait: The political battlefield for AIDS research and treatment is juxtaposed with contemporary events in 1990s US involvement in Kuwait.

Read Now >/8 Completed

Historical Biology and Anachronistic Hetero/Cisnormativity

Bagoas/Bagoe Pleads on Behalf of Nabarzanes in The Book of the Deeds of Alexander the Great, about 1470–75, Master of the Jardin de vertueuse consolation (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIV 8, fol. 133v)

History is the record of the past that scholars and publics choose to remember. For example, the 4th-century B.C.E. ruler Alexander the Great consolidated territory in the Mediterranean and expanded the Macedonian and Greek empires into Western and Central Asia. Oral traditions passed down events from his life, including accounts that he had a range of lovers such as the young man Hephaistion and a eunuch called Bagoas. The Romans described his life in Latin texts, and throughout the Middle Ages, writers added to and updated his biography in every European language and some accounts from Persia to Ethiopia. In the 1470s, a Portuguese humanist named Vasco da Lucena penned a French account of Alexander’s life to serve as a model for Duke Charles the Bold of the Burgundian Netherlands and others at his court. “In order to avoid a bad example,” the writer tells us that he regendered Bagoas and other male or eunuch lovers as female, thus introducing Bagoe (the feminized version of the figure’s name) to the narrative. The artist followed suit and juxtaposed Bagoe with the queen of the legendary Amazon warriors (depicted in the illumination in the background at right). For readers at the time, same-gender relationships were considered non-normative despite the prevalence of such couplings across all ranks of society and around the world, and powerful female rulers were also to be feared (in this European context). This version of history was precisely what its audience wanted but I wonder how such presentations of the past would be received today. We can look to film adaptations of Alexander’s life to see what this ancient figure means to viewers today. For example Oliver Stone’s 2004 Alexander included both Hephaistion and Bagoas, as well as female lovers, thus foregrounding the ruler’s fluid sexuality.

One of the challenges of wading through historical records is that people of the past have expressed a range of ideas about bodies, genitals, and the relationship (or not) between those physical aspects of an individual and their sexual or emotional attraction to others. Historical biology considers ways that people have understood bodies and their functions in the past, with ideas and beliefs that may seem quite different from those in the present. Widely understood today is that genitals do not equal gender. Genitals are an outward feature that doctors use to assign sex at birth: as female, intersex, or male. Gender identity is how an individual self-identifies and gender expression is their outward presentation of gender. Physical and emotional attraction can constitute a person’s sexuality. Scholars have long recognized the presence of individuals who do not fit into the simple and entirely modern categories of male and female, precisely because biological sex and societally constructed or prescribed gender are complex and varied, as we’ve seen. Let’s take a closer look at the sex spectrum with some historical examples.

Hasanlu Couple, 9th century B.C.E., West Azerbaijan Province of Iran (Penn Museum)

In the 9th century B.C.E., the site of Hasanlu in present-day Iran was destroyed by fire. Amidst the remains is a pair of individuals known as the Hasanlu Couple (or Lovers). Evidence suggests that they are both biologically males, the one at left being about 30–35 years old and the one at right being about 19–22. Similar couplings have been found elsewhere in the ancient world, at Pompeii for example (where figures died from asphyxiation related to the smoke of Mount Vesuvius’s eruption). It’s problematic to read these figures as necessarily queer, however. Often popular media conflates gender, gender identity or expression, and sexuality, when each can be both determined by a specific time and place (culture) and by an individual. But this example reveals challenges posed to archaeologists when working with a binary of male/female and with an assumption that heterosexuality is normative (it’s not). The past was far more fluid.

Stirrup-spout ceramics of individuals engaged in sexual acts. Left: Moche (Lima, Larco Museum); right: Chimú, 1000–1400 (Madrid, Museo de América)

The challenges in interpreting sexual acts of the past are clearly conveyed in ancient art from the Andes in South America. Ceramic vessels of the Moche and Chimú peoples include individuals engaged in a variety of sexual acts and positions, from masturbation to vaginal, oral, and anal sex. Setting aside preconceptions about sex and procreation, we can focus instead on what the objects depict and the frequency of their depictions in this media. In these instances, penetrative sex was varied and bodies were at times gendered male, female, or intersex based both on anatomy and on dress, hairstyle, jewelry, and more. Engaging with the past requires us to set aside ideas or biases about what may have been considered normative for a specific time and place.

House Altar depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti and Three of their Daughters, limestone, New Kingdom, Amarna period, 18th dynasty, c. 1350 BCE (Ägyptisches Museum/Neues Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep IV, who changed his name to Ahkenaton, is famous as the husband of Nefertiti and father of Tutankhamun. Ahkenaton is often described as having an androgynous appearance. Some archaeologists have posited that he may have had Kleinfelter’s syndrome, which might account for the enlarged breasts and also the shape of the pelvic bone. Some ancient rulers desired to present themselves as androgynous or to confirm their gender identity surgically, which was not the case, so far as we know, with Ahkenaten. Roman emperor Elagabalus, however, is sometimes considered a trans ancestor (or trancestor). The ruler is reported to have desired castration, a possible ancient equivalent of sex confirmation surgery. Some contemporary reports refer to Elagabalus using she/her pronouns.

Sleeping Hermaphroditus, 2nd century C.E. marble copy of an original from the 2nd century B.C.E. (Rome, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme; photo: Folegandros, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The problematic term “hermaphrodite” comes from the ancient Greco-Roman deity Hermaphroditus, the child of the gods Hermes and Aphrodite, who is often represented with large breasts and a penis. Ancient artists at times sculpted this figure with the intent to fool the viewer into thinking they were viewing a cis-woman from one angle, only to see the penis from another angle. Numerous later artists—including Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Diego Velázquez, François Duquesnoy, and Barry X Ball—produced copies of the sculpture. This centuries-long ploy of attempting to “fool” the viewer denigrates intersex and trans bodies by making them objects of jest rather than dignifying them.

Left: Ardhanarishvara, relief sculpture from the Elephanta Caves, 5th–7th century C.E., Mumbai, India (photo: Isabell Schulz, CC BY-SA 2.0); right: Guanyin of the Southern Sea, China, 11th/12th century, Lio (907–1125) or Jin Dynasty (1115–1234), polychromed wood (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art)

South and East Asian art offer several pathways for exploring gender fluidity. In Hinduism, Shiva and Parvati are two prime deities. When their natures are combined, they become Ardhanarishvara, an androgynous figure. Androgyny was considered one of the highest states in several cultures, as the perfect combination of male and female qualities. From India to China and beyond, Buddhists revere bodhisattvas, compassionate beings who forgo the release from suffering known as nirvana. One such individual is Avalokiteshvara (called Guanyin in China), who is alternatively represented as male or female or with varying features that defy strict gender categorization.

Archaeological finds, like the Hasanlu Couple, of individuals buried with objects that seem to transcend clear gender boundaries might point to the possibility of non-binary identity in the past. Burials around Stonehenge (England) have been described as male or female based on the presence of daggers or knife-daggers, respectively. At least one person was buried with both types of objects, as well as an amber necklace usually associated with female burials. Could this array of materials be a very early sign of expanded gender identity? Similarly, a Norse warrior was buried with objects associated with cisgender men (sword) and cis-women (lavish jewelry and clothing style), leading some scholars to suggest that they were a female warrior but more recent study suggests that the individual was intersex and had Kleinfelter’s syndrome.

Left: Juan van der Hamen (attributed), Alonso Díaz de Guzmán, c. 1626, oil (Fondación Kutxa); right: Thomas Stewart, Chevalier d’Eon, after Jean Laurent Mosnier, 1792, oil on canvas (London, National Portrait Gallery)

Finally, several famous individuals—rulers, knights, religious figures, saints, and more—were assigned one sex at birth but changed their names and lived, dressed, and navigated society as the gender that matched their identity or to avoid the expectations for their assigned sex. Two such prominent figures are Alonso Díaz de Guzmán (assigned Catalina de Erauso at birth) and the Chevalier d’Eon (Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée d’Éon de Beaumont). After a time as La Monja Alferéz (meaning the standard-bearing nun), Catalina de Erauso took the names Alonso Díaz de Guzmán and alternatively Antonio de Erauso while traveling throughout Spanish territories. Questions continue to emerge about what pronouns to use to describe the individual and how they may have identified in terms of gender and sexuality. Similarly, the Chevalier d’Eon served in culturally male positions of diplomacy and military before fully presenting as female for the remainder of her life. She was famous in her time, amid rumor and speculation about her sex. Additional examples from the resources below expand the geographical scope of this survey by taking us to a few sites in the Americas, and also includes examples from Egypt, France, and French Polynesia.

Watch videos and read essays that address gender identity and sexuality

Mortuary Temple and Large Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut: Represented as both traditionally male and female, Hatshepsut provides a powerful case study about gender in ancient Egypt.

Read Now >

House Altar depicting Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and Three of their Daughters: A pharaoh’s biological condition may be on view in this private relief altar.

Read Now >

Doe Shaman Effigy: Magical human-animal beings can often be read as having the potential to queer traditional ideas about gender, that is to destabilize them.

Read Now >

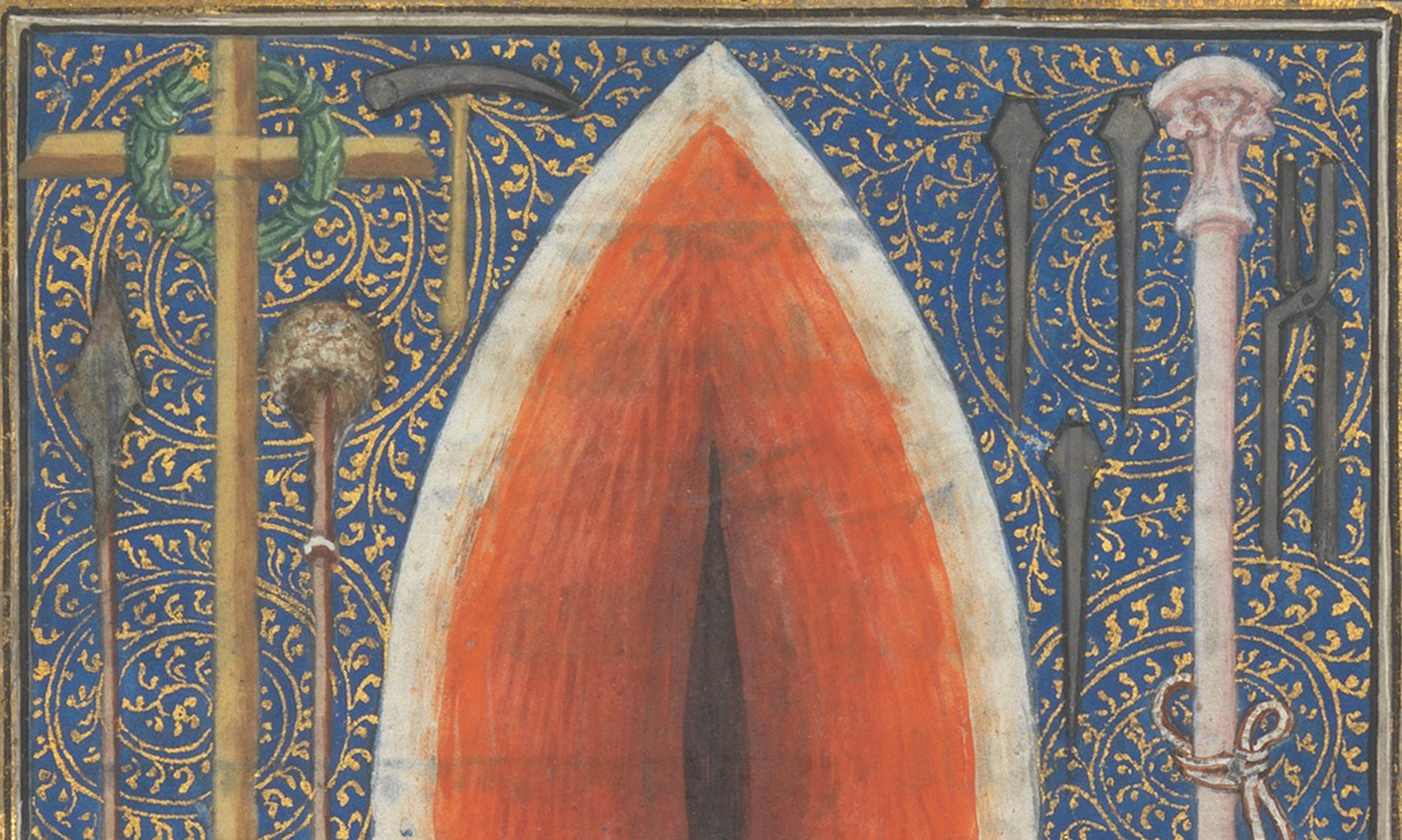

Mysticism and Queer Readings of Christ’s Side Wound in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg: Associations between Christ’s side wound, the vagina, and female devotion emerge in several private prayer books.

Read Now >

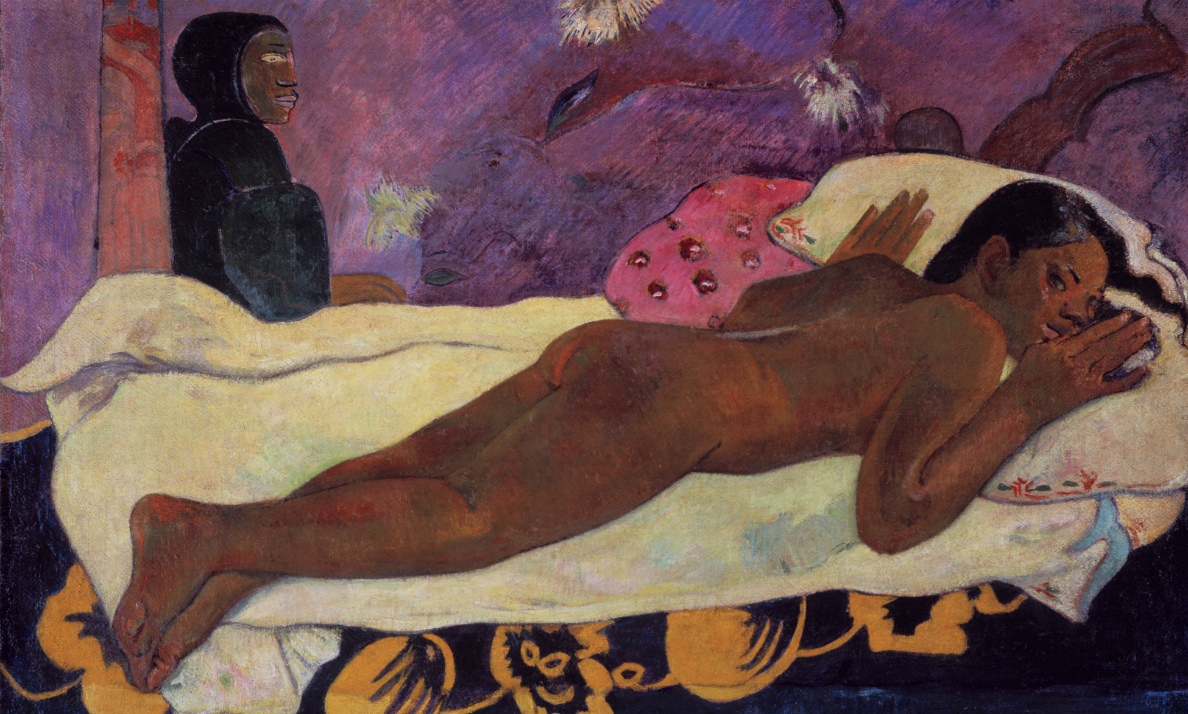

Paul Gauguin, Spirit of the Dead Watching: European encounters with expansive gender identities reveal misunderstandings and prejudices.

Read Now >/6 Completed

Chosen Families in World Art History Today: Our Vibrant Past and a Limitless Future

The terms we use to describe ourselves today‚ as LGBTQIA2+ individuals—are part of an ever-expanding vocabulary of identity. An equally wide-range of related terms can be found in the material records of the past, sometimes used by people to describe themselves and at other times used derogatorily toward those with expansive ideas about gender and sexuality. Let’s look at a few examples from around the world.

Gala Priests, from the Temple of Inanna at Mari, about 2450 B.C.E. (Musée du Louvre)

In Sumer, a region of ancient Mesopotamia, priests referred to as gala may have constituted a non-binary gender identity: many were depicted in societally-defined male dress but were shown beardless and in texts were described with conventionally female characteristics. The term gala is made up of cuneiform, or wedge-shaped, signs meaning “practitioners of anal sex,” yet it appears that some had a wife and children (after all, anal sex is practiced by people regardless of sex or sexuality).

Gallus Priest Sacrificing to Cybele, from the Isola Sacra Necropolis, 3rd century C.E. (Rome, Museo Archeologico Ostinense; photo: Sailko, CC BY 3.)

In ancient Rome, a gallus was a eunuch priest to the earth-goddess Cybele. These individuals were often referred to with the pronouns “she/her” but also derided as “half-men.” Eunuchs represent interesting case-studies in world history: they’re often described as asexual, due to the various forms of castration (in the case of the galli, some were self-castrated), but in other contexts are described with misogynistic language.

Dante and Virgil Meet the Soul of Brunetto Latini and “Sodomites,” in Divina commedia, canto XV, Priamo della Quercia, Siena, 1444–50 (The British Library, Ms. Yates Thompson 36, fol. 27)

In many parts of western Europe during the medieval and early modern period, the term sodomite applied to any sexual act that did not lead to procreation (such as simply enjoying sex, solo or mutual masturbation, rubbing bodies or genitals together, oral and anal sex, sexual practices or assault in same-gender contexts, or an accusation of sex work by male-identifying persons). The association of sodomy as a male-to-male sexual relation punishable by death and condemnation to hell emerged in Dante Alighieri’s Inferno of the early 1300s. The poet encountered his mentor, Brunetto Latini, amidst a group of “sodomites” who offer a warning against the so-called “unmentionable vice.” Accusing a fellow citizen of sodomy was a common political tactic, and many European cities had laws regulating such activities and punishments if found guilty.

The Embassy of the Duke of Brabant before the King of France and the Duke of Berry in Jean Froissart’s Chronicles, about 1480–83, Master of the Getty Froissart (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIII 7, fol. 272v)

When writing about the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453), Jean Froissart added a gossip-ridden aside about Jean, the Duke of Berry, noting that he was infatuated with a young man named Tacque-Tibaut who specialized in manufacturing knitted undergarments. Decades later, a manuscript illuminator incorporated the duke and his paramour in a royal throne room setting. The duke places one hand on the throne and one on the shoulder of the youth. These acts of historical “outing” has inspired art historians to look for possible queer readings in the objects commissioned by the duke.

Intersex Figure Reaching for a Dagger, Dogon Peoples, Mali, date not now known, wood, 47.3075 x 10.795 x 12.7 cm (New Orleans Museum of Art)

Turning to premodern Mali in West Africa, we learn that Nommo are ancestral spirits who are described as androgynous or intersex. Gender transformation among followers of such deities is documented in more than twenty African societies prior to colonization.

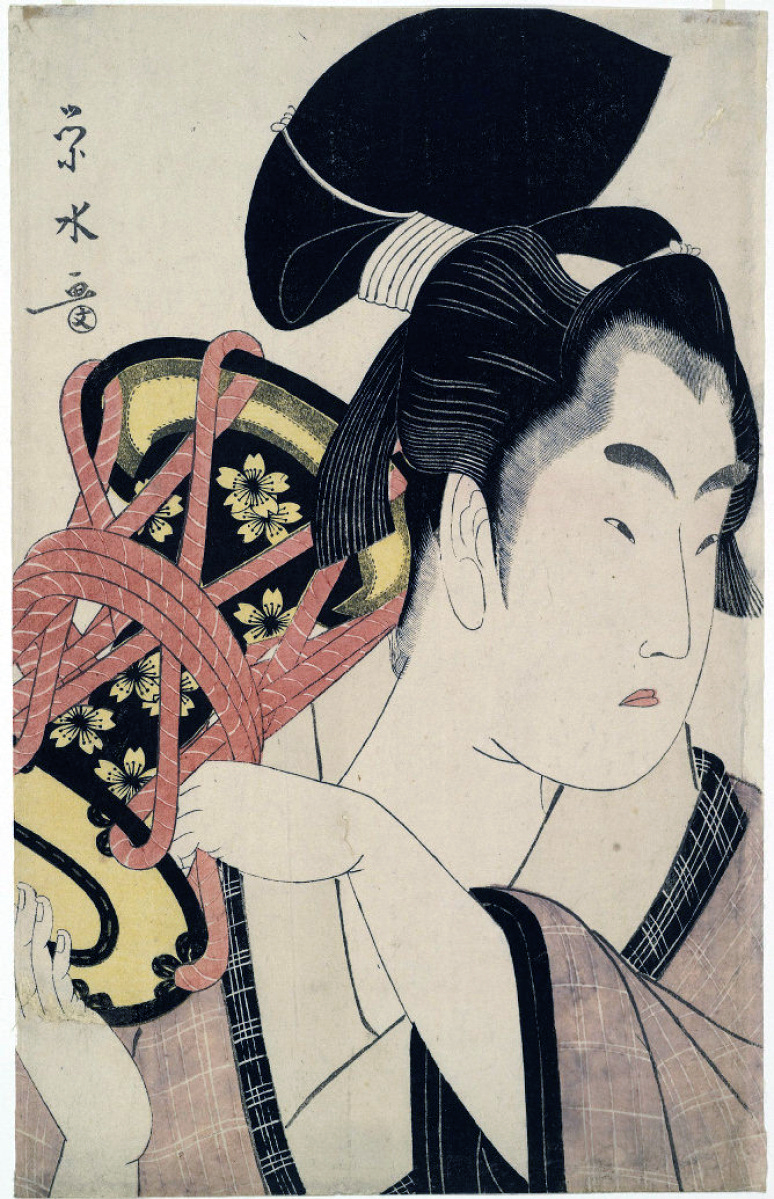

Hosoda Eisui, Wakashu with a Shoulder-Drum, late 18th or early 19th century (Toronto, Royal Ontario Museum)

In early modern Japan, the term Wakashu described adolescents who were assigned male at birth but who presented as female. They were understood as a third or separate gender category of their own, one that was sexually ambiguous, and they were attracted to and desired by men and women alike. They are recognized in art by the partially shaved crown of the forehead, which would be completely shaved once a cisgender male came of age after puberty.

For the Maori, the term Takatapui refers to an intimate companion of the same sex but can now refer to a full spectrum of queer couplings (including those who identify as heterosexual and have sex with members who identify as the same gender). The fluidity of sexual relationships on the treasure box mentioned earlier comes across clearly.

Bahuchara Mata Riding a Cockerel Vahana (mount), attended by Gorabhairava and Kalabhairava, Mewar, about 1820-40, gouache on paper (photo: Peter Blohm, CC0)

In India and South Asia, the term hijra can describe eunuchs, intersex or transgender people, or more properly a third gender or gender ambivalence. The word dates back to antiquity, with references in the Kama Sutra text on erotica and sexuality. Bahuchara Mata is one of the various Hindu deities who is a patron for trans communities in India.

As we saw at the start, in Indigenous American contexts the term two-spirit can refer to an individual who identifies with both traditionally masculine and feminine characteristics in reference to gender, sexuality, or gender expression.

Watch videos and read essays that draw connections between past and present ideas about identity and human experiences

The Cave of Shiva at Elephanta: Amidst the pillared hall dedicated to Shiva is an androgynous representation of the ruler combined with Parvati.

Read Now >

Coming Out: Queer Erasure and Censorship from the Middle Ages to Modernity: What did it mean to be queer in the Middle Ages? And why have modern artists been drawn to this period of the past? This essay offers some suggestions.

Read Now >

Catherine Opie, Self-Portrait/Cutting: A family portrait reveals painful aspects of queer parenting and elements of BDSM.

Read Now >

Gertrud Arndt, Self-Portrait with Veil: Femininity is compared with “drag,” the act of dressing as one of the opposite gender or to obscure clear-cut gender identification.

Read Now >

Kehinde Wiley, Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps: Placing people of color in prominent compositions from European art history, Kehinde Wiley also queers the material with his choice of models.

Read Now >/5 Completed

This brief selection of terms hopefully serves to demonstrate that queer and trans people have always been present throughout time and across the planet. More and more such examples from art history, archaeology, anthropology, and other cultural studies of humanity continue to come to light. Teaching and learning about gender and sexuality liberates everyone from limiting categories of identity and shows queer and trans folx that we are valuable today and in the future.

Acknowledgments

My sincerest thanks to Lauren, Beth, and Steven for encouraging and supporting this chapter, and for their helpful suggestions throughout. I am also grateful to Karl Whittington for being a constant interlocutor and for offering edits to drafts of this work; and to Rosamund Garrett, Kathy Dumlao, and colleagues at the Memphis Brooks Museum for inviting me to share an early version of this chapter with their audiences. Conversations with the following individuals continue to shape my understanding of queer and trans history—I am thankful for every one of you: Ron Athey, Roland Betancourt, Jenny Bledsoe, David Carrillo-Rangel, Cynthia Colburn, Jonah Coman, Sarah Cooper, Leah DeVun, Larisa Grollemond, Gerry Guest, Arpad Kovacs, Rheagan Martin, Rashaad Newsome, Nina Rowe, Michelle Sauer, Nancy Thompson, and Andrew Westover. Thank you to my parents, grandparents, and especially to Mark Mark Keene for your love and wisdom.

Key questions to guide your reading

How have communities around the world and throughout time represented ideas about gender and sexuality in works of art?

Where can we find evidence of gender diversity and same-gender relationships in the past?

What words have people used to describe their identity and the identities of those around them? How do these relate to the acronym LGBTQIA2+?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow have communities around the world and throughout time represented ideas about gender and sexuality in works of art?

Where can we find evidence of gender diversity and same-gender relationships in the past?

What words have people used to describe their identity and the identities of those around them? How do these relate to the acronym LGBTQIA2+?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Hetero- and cis(gender)-normativity

Historical Biology

Intersex (vs. Hermaphrodite)

LGBTQIA2+

Queer and trans art history

Sex spectrum

Sodomy

Learn more

A Syllabus on Transgender and Nonbinary Methods for Art and Art History

Transgender Lives in the Middle Ages through Art, Literature, and Medicine by Roland Betancourt

The Cluny Adam: Queering a Sculptor’s Touch in the Shadow of Notre-Dame by Karl Whittington

Introduction to Gender in Renaissance Italy

Confronting Power and Violence in the Renaissance Nude

Copying as Innovation and Resistance

Restoring Ancient Sculpture in Baroque Rome

A Brief History of the Arts of Japan: the Edo Period

Graciela Iturbide: Photographing Mexico

LGBTQ Histories in The British Museum (a Google Arts and Culture presentation)