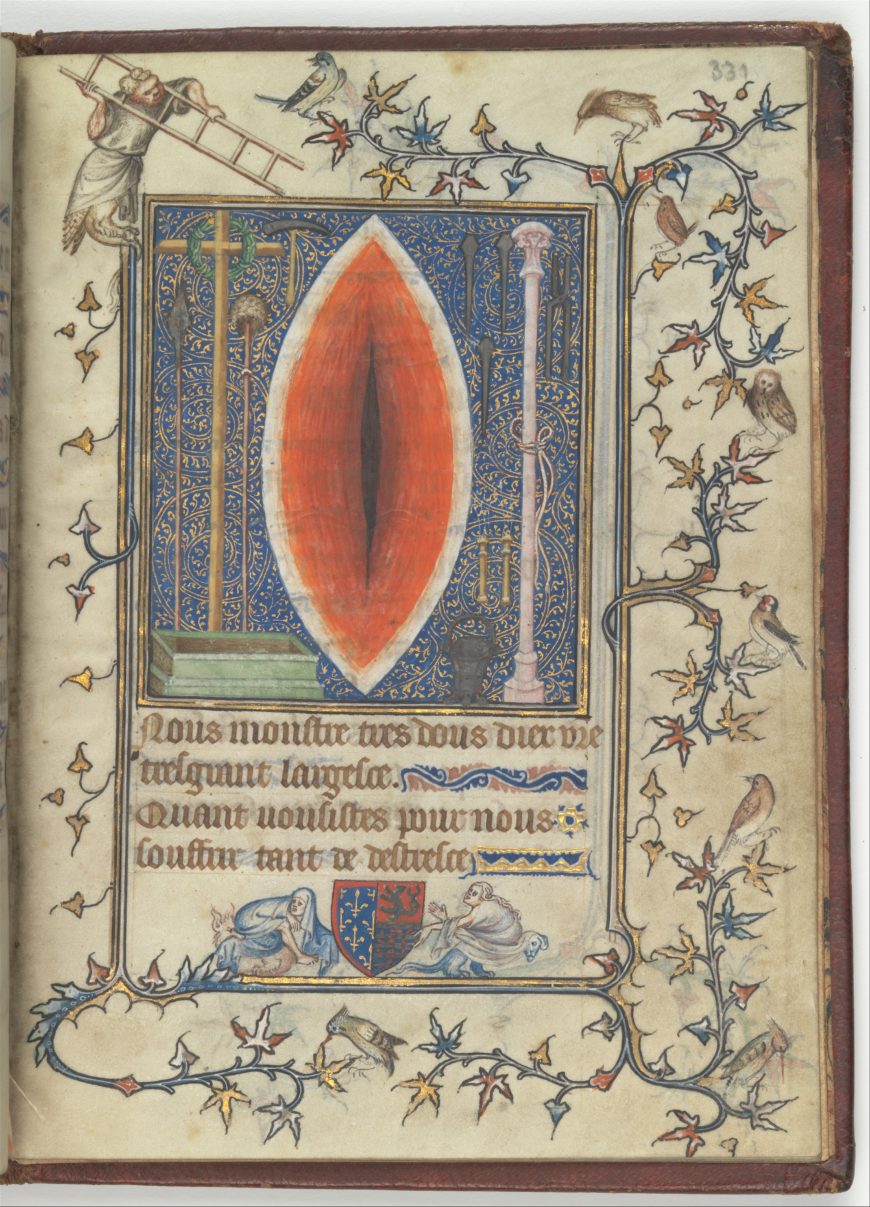

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?), and workshop, Miniature of Christ’s Side Wound and Instruments of the Passion, folio 331r, in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, before 1349 (The Cloisters Collection)

Deluxe medieval devotional books used images and texts together to produce compelling, spiritual experiences for their readers. One particularly dramatic image confronts the reader from the pages of a book made for a woman, Bonne of Luxembourg, in the French royal family. In the center of the parchment page, on a blue field teeming with scrolling golden vines, the instruments used to torture Christ during the Passion stand arranged for the viewer’s inspection.

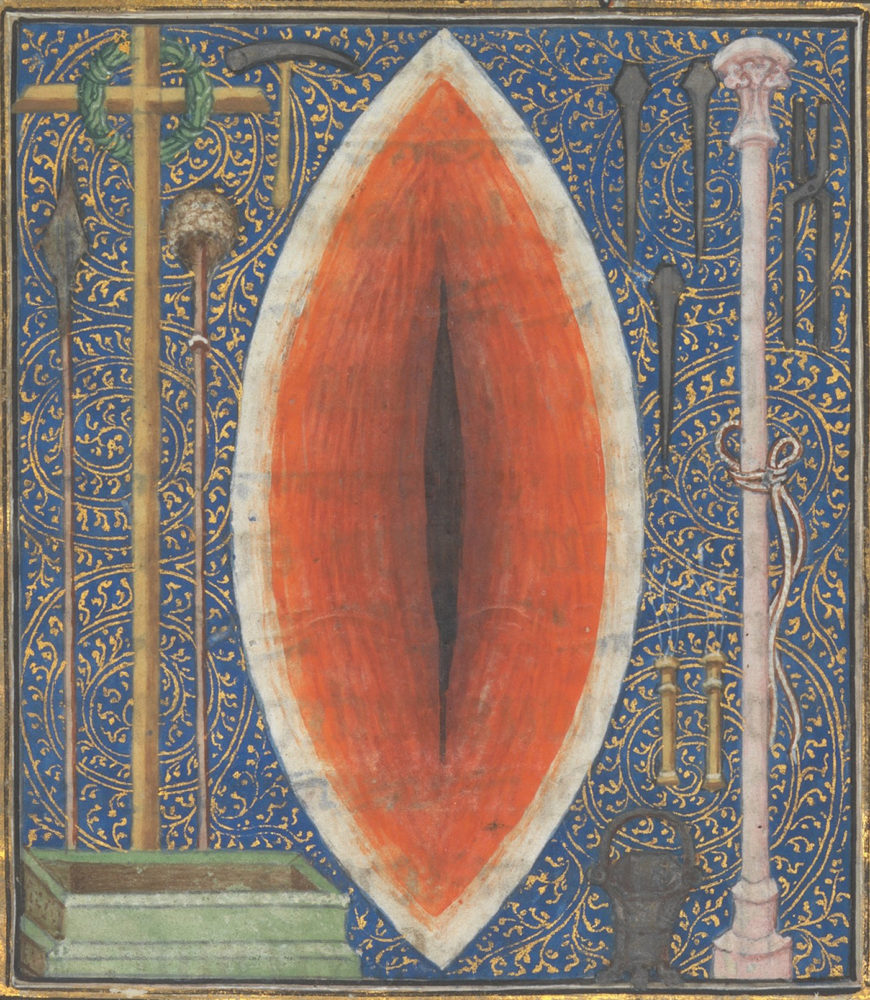

In the center, filling the composition from top to bottom, is a gaping, disembodied wound. Framed with an almond-shaped ring of white flesh, the bright orange-red tones of torn flesh deepen in color closer to the irregular, vertical brown gash in the center. This is the spear wound created in Christ’s side after his death on the cross, isolated for the pious reader’s contemplation. Shown at what medieval Christians believed to be actual size (about 2 inches), the wound dominates the composition while the miniature instruments of torture that surround it seem to fade into the background. Along with the text (a prayer describing Christ’s suffering), and the manuscript’s lively margins, this graphic painting worked to engage viewers in emotional contemplation of Jesus’ sacrifice.

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?), and workshop, Miniature of Christ’s Side Wound and Instruments of the Passion, detail, folio 331r, in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, before 1349 (The Cloisters Collection)

In the Middle Ages, this powerful image was meant to orient pious readers’ attention to Christ’s body and the physical suffering he endured to ensure their salvation. This emphasis on Christ’s body is part of a larger trend in late medieval devotion known as affective piety, in which compassion for Christ’s suffering held the key to salvation. With its almond shape, vertical orientation, and confrontational placement, the wound of Christ in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg might remind a modern viewer of the Eye of Sauron (known from J.R.R. Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings). Medieval viewers likely overlaid other associations onto such images of Christ’s wound. The change in the wound’s orientation from a diagonal slit to a vertical opening and the isolation of the wound as an almond-shaped device transform it into an image strongly reminiscent of medieval representations of the vulva and the vaginal opening. Similar imagery persists in modern visual culture, such as Judy Chicago’s 1979 installation The Dinner Party. This association of Christ’s side wound with female reproductive organs has connections with mystical writings that eroticized the body of Christ and that emphasized its nurturing and generative qualities.

The Manuscript Context

Although we often think of paintings today as freestanding, portable objects, paintings in medieval books were not meant to be isolated from their manuscript context. When closed, Bonne’s prayer book measures just over five inches high—smaller than an adult’s hand. This small size distinguishes personal prayer books from books sized for display, like the Winchester Bible. Deluxe prayer books like Bonne’s were status symbols, but they were also intimate, personal objects that facilitated direct communication with God.

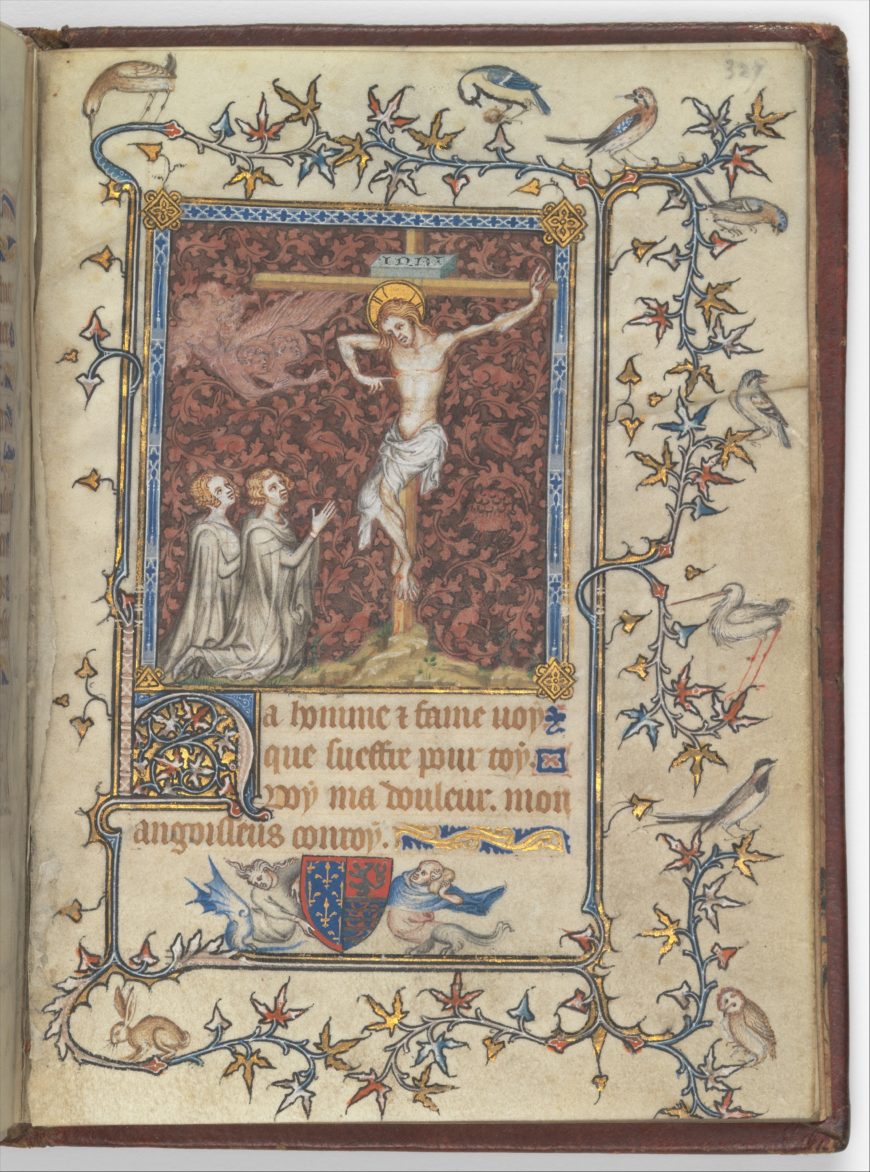

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?), and workshop, miniature of the Crucifixion with Christ displaying his side wound to Bonne of Luxembourg and John, Duke of Normandy, folio 328r, in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, before 1349 (The Cloisters Collection)

The image of Christ’s side wound is one of fifteen miniatures distributed among the 334 folios of the prayer book. Each miniature introduces and illustrates the themes of the manuscript’s most important texts. The miniature of the wound comes in the midst of the final text, focusing on Christ’s experience on the cross.

Jean le Noir, Bourgot (?), and workshop, miniature of the Crucifixion with Christ displaying his side wound to Bonne of Luxembourg and John, Duke of Normandy, detail, folio 328r, in the Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, before 1349 (The Cloisters Collection)

This text opens with a miniature of the crucified Christ showing his side wound to two kneeling figures: Bonne and her husband, the future French king John the Good. Viewed in sequence, the miniature with the crucified Christ instructed Bonne (personally!) where to focus her devotional attentions, while the miniature of the wound three folios later provided her direct, visual access to it. The wound provides a dramatic climax to the prayer and the book.

Mysticism and Queer Readings

Devotion to Christ’s side wound emerges from late medieval Christian mysticism, writings by monastic men and especially women articulating their personal, visionary, and ecstatic experiences of the divine. In mystical writings, Christ’s body often takes on feminine qualities, becoming permeable, generative, and nourishing. Catherine of Siena’s biography records a vision in which Christ nourishes the mystic from his side wound, an encounter that is simultaneously maternal and erotic:

With that, he tenderly placed his right hand on her neck, and drew her towards the wound in his side. ‘Drink, daughter, from my side,’ he said, ‘and by that draught your soul shall become enraptured with such delight that your very body, which for my sake you have denied, shall be inundated with its overflowing goodness.’ Drawn close in this way, … she fastened her lips upon that sacred wound, … and there she slaked her thirst.[1]

Images of the side wound and the mystical tradition from which they emerge have provided fertile material for scholars engaged in “queering” the Middle Ages. Queering means questioning assumptions of heterosexual and cisgender normativity in the past, providing a critique of modern scholarship in the process.

The image of the side wound, like Catherine’s vision, grants feminine bodily attributes to Christ, destabilizing assumptions about his gender. In mystical images and texts, Christ’s capacity to transcend the gender binary, like his capacity to transcend the binary of life and death, underscores his divinity. Christ is not the only figure within medieval culture to transgress the gender binary. Medieval literature—religious and secular alike—is replete with transgender figures, from saints like Marinos the Monk and, perhaps, Joan of Arc, to the fictional protagonists of the thirteenth-century romances Silence and Yde et Olive.

While the voices of actual marginalized people are rarely recorded in medieval documents, Eleanor Rykener is a striking exception. Arrested in late fourteenth-century London for sexual misconduct, and named in court records as John, she identified herself as Eleanor in her testimony. While the gender-ambiguous Christ is a social construction, it can nevertheless call our attention to individuals and groups hidden within or excluded from the historical record and give modern students a means to consider their positions and experiences within their time.

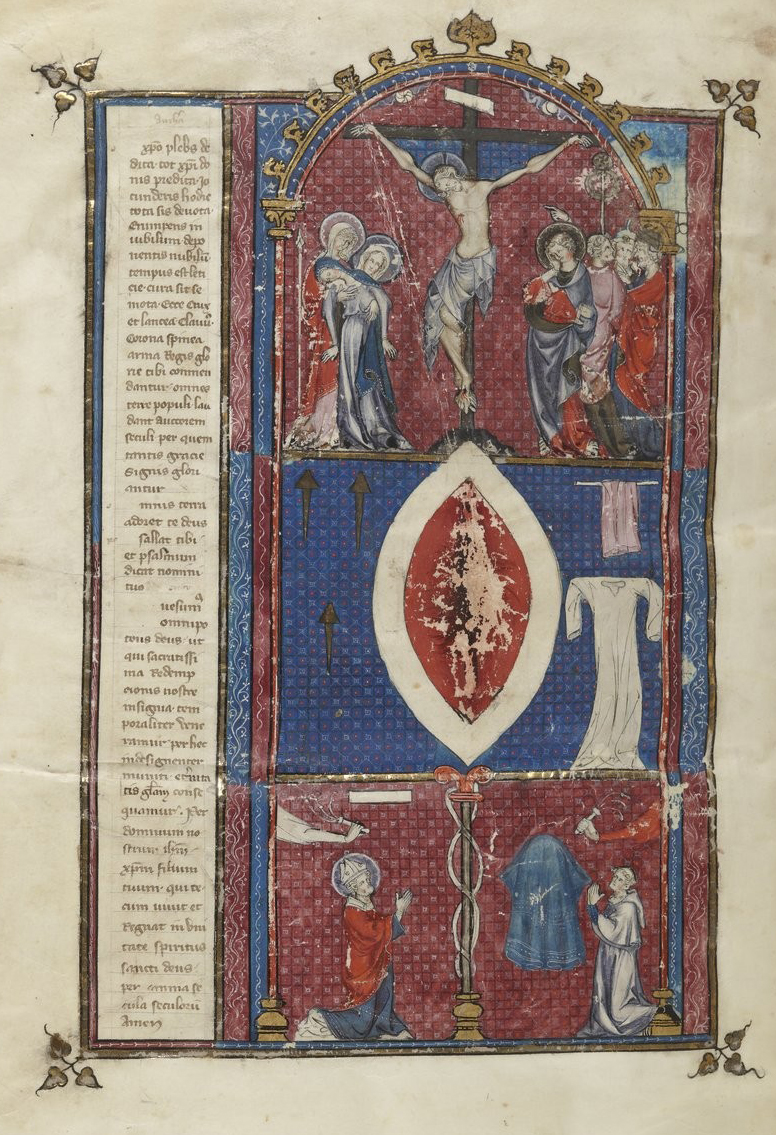

The Fauvel Master, miniature of the Crucifixion, the wound of Christ, and the instruments of the passion, detail, folio 140v, in L’Image du monde of Gossouin of Metz, c. 1320-1325 (Bibliothèque nationale de France ms. fr. 574)

Echoing the eroticism of Catherine’s vision, medieval readers’ interactions with their devotional books could be very intimate, including the touching or kissing of images, and other images of the wound of Christ show paint loss from readers’ pious stroking of the paint. Such devotion to Christ’s side wound further destabilizes presumptions of heterosexuality in medieval and much modern thought. With its focus on touch and penetration, the devotion of men and women alike to Christ’s side wound had the capacity for queer connotations. The ragged, parted lips of Christ’s wound carried many meanings for their medieval viewers, from the pleasures of being enveloped in divine love to protections in childbirth.

Limbourg Brothers, January, from Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, 1413-16, ink on vellum (Musée Condé, Chantilly, fol. 1v)

Bonne, who was married at seventeen to the French royal heir and bore nine children before her death of plague at age 34, may have found these associations with pregnancy particularly meaningful. However, the reproductive and the erotic resonances of the image are not mutually exclusive, and, regardless of Bonne’s sexuality, we can see in this imagery a potential model for same-sex desire in the Middle Ages. Such models are crucial for the study of sexualities in a period when homosexual relationships, especially between women, were rarely acknowledged in mainstream texts or conversations. When references to homosexuality do appear in medieval art, it is often framed as a sin, as in the representations of “sodomy” in moralized bibles. Still, more subtle, positive references to homosexual identities may be found. Medieval gossip about Bonne’s son, Jean, Duke of Berry, implies that he may have been attracted to men. Art historian Michael Camille has suggested that Paul de Limbourg devised several well-dressed young men in the feasting miniature of the Très Riches Heures for the duke’s pleasure.

Artists, Patrons, and Owners

The images and texts of Bonne of Luxembourg’s prayer book contained many layered messages for its royal reader. While the content of images and texts alike would have been planned by a devotional adviser, the paintings are attributed to Parisian illuminator Jean le Noir and his workshop, which by 1358 included his daughter, Bourgot, in a prominent role. The commercial book shops of the late Middle Ages were collaborative, often family enterprises, with men and women of different generations working side-by-side. Three artists’ hands have been identified within the manuscript, though it is not possible to know which belonged to Jean, Bourgot, or other workshop members.

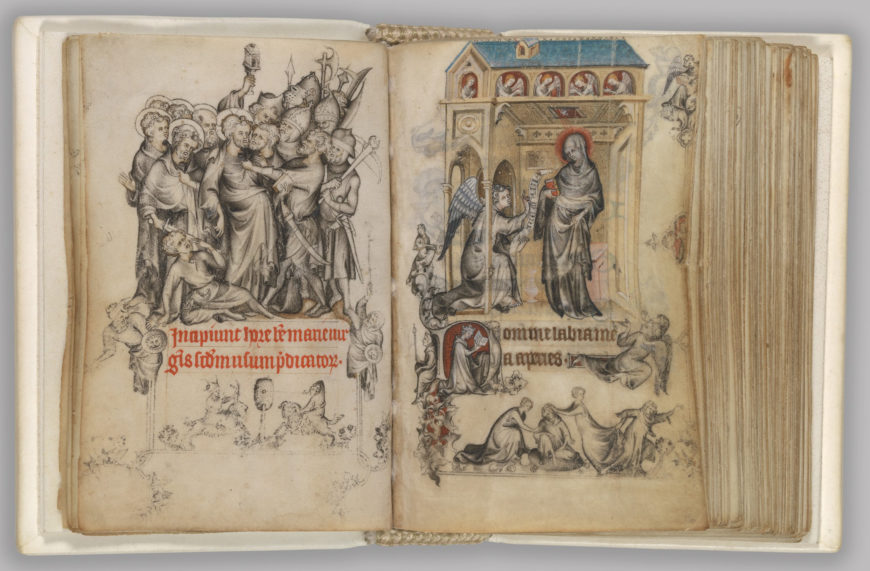

Jean Pucelle, opening pages showing the Arrest of Christ, the Annunciation, Queen Jeanne d’Evreux in prayer, and erotic games in the margins, fols. 15v–16r, in the Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, c. 1324-1328 (The Cloisters Collection)

Jean le Noir’s workshop specialized in the grisaille style of painting first popularized among the royal patrons of France during the previous generation by illuminator Jean Pucelle. The Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg looks back both in style and in content to the miniature prayer book Pucelle made for an earlier queen of France, Jeanne d’Évreux, between about 1324 and 1328.

While the imagery of Bonne’s prayer book brought her into intimate contact with God, its style connected her with the royal French line. These connections were carried forward by Bonne’s children, particularly Jean de Berry, who around 1371 commissioned a prayer book with the same Passion texts as his mother’s from the now elderly Jean le Noir. These stylistic, thematic, and textual traditions across generations speak to the complex dynamics of transgression and normativity within medieval manuscript patronage at the highest levels.