In this drawing, both the Apollo Belvedere (on the left) and the Laocoön on the right, are depicted with their 16th-century “restorations.” Federico Zuccaro, Taddeo in the Belvedere Court in the Vatican Drawing the Laocoön, c. 1595, pen and brown ink, brush with brown wash, over black chalk and touches of red chalk, 17.5 x 42.5 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

Early Modern fascination with the “Antique”

In this late 16th-century drawing by Federico Zuccaro, we see the artist’s older brother, Taddeo, surrounded by Greek and Roman sculptures in the Vatican’s Belvedere courtyard in Rome. Taddeo is seated on a cloth spread upon the ground, hunched slightly forward, with his sketchpad resting on his thighs, concentrating on drawing the famous ancient sculpture, the Laocoön. His back is to yet another very famous ancient sculpture, the Apollo Belvedere. Both of these sculptures were unearthed during the Renaissance, and of course, given that more than 1,000 years had passed, they were discovered buried and broken. Both were restored by Renaissance and Baroque artists. While today’s museums contain limbless torsos, solitary hands and feet, and disembodied heads, in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was fashionable to present sculptures with fully formed bodies, whether or not the work of art was actually preserved that way. Restoration was the process by which ancient Greek and Roman fragments of sculpture were provided with new components to make them “whole” once again.

The Laocoön is an interesting case in point. It was discovered early in the 16th century (according to one source, Michelangelo was called to be present for its excavation) and depicts the priest Laocoön and his sons being strangled by snakes. The sculpture—which was very important for Renaissance and Baroque artists—was found in pieces, and when reconstructed, the most important missing component was an arm belonging to the priest.

Left: Photograph of the Laocoön with reconstructed arm raised upward, and right, the Laocoön with its original arm bent backward as it appears today. Left: James Anderson, Laocoön, c. 1845–55, albumen silver print, 39 x 29.5 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum); right: Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums)

Pope Julius II, who brought the sculpture to the Vatican’s Belvedere courtyard, was not content to display the sculpture as it had been found. He first commissioned Jacopo Sansovino, followed by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (a student of Michelangelo), to create the missing arm. These additions (or restorations), to the Laocoön each consisted of a dramatically upraised arm, visible in many reproductions of the sculpture (and in the drawing by Zuccaro above). It was only in the beginning of the 20th century when the sculpture’s real missing arm was discovered. It turns out this arm was not upraised at all, but was bent backward. This proved that Montorsoli’s original restoration, as well as a later 18th-century restoration (also with an upraised arm), were incorrect. It is the original, bent arm that is visible on the Laocoön today.

Apollo Belvedere in the Vatican Museums today, shown with a detail of the drawing above by Federico Zuccaro where we can see a restored bow in Apollo’s left hand. Apollo Belvedere (Roman copy of a Greek(?) original), original late 4th century B.C.E. marble, 2.3 m high (Vatican Museums, Rome)

Going back to Zuccaro’s drawing, we see the Apollo Belvedere holding a bow—yet another of Montorsoli’s reconstructions (you won’t see this when you visit the sculpture in the Vatican today). Restoration became a steady source of employment for sculptors, especially for those who could not always attract wealthy patrons. Even the greatest of Baroque sculptors, such as Gianlorenzo Bernini and Alessandro Algardi, received commissions for restorations, although this was usually at earlier stages in their careers and with much less frequency than other, less successful sculptors. Restorations in the Renaissance and Baroque periods might not always have produced sculptures that were “correct” in terms of classical (Greco-Roman) iconography. But even when carried out correctly, restorations have added a new level of meaning to the works that was not present in antiquity.

Not every artist in Renaissance and Baroque Rome had access to ancient Greek and Roman statues. Drawings depicting artists with antiquities—like the one by Federico Zuccaro—are testaments to the status of a particular artist. It was a privilege to be allowed to view works of art in the papal or other princely collections face-to-face. In later periods, artists would come into contact with famous antiquities mainly through prints, or less commonly, plaster casts made in Rome and shipped throughout Europe. But these were poor replacements for the prestige of owning actual antiquities. While popes, cardinals, and princes had been the owners of collections of ancient statuary since the Renaissance, as more and more wealthy non-Italians came to Rome on the Grand Tour, they desired collections of their own. The allure of the classical, in sculptural fragments or architectural ruins, continued into the 18th century and helped give shape to the modern world. This passion for collecting encouraged the growth of the restoration industry, resulting in Rome, Florence, Paris, and London becoming centers for the buying and selling of ancient sculpture.

A treatise on restoration

The most complete primary source for restoration in the 17th century is Observations Concerning Ancient Sculpture by Orfeo Boselli. This treatise emphasized classical sculpture’s place as the starting point in the education of a Baroque sculptor. According to Boselli, since many ancient sculptural figures were found lacking their identifying attributes (often the item that they carried; for example, Apollo often holds a lyre or a bow), it was important for restorers to learn the attributes of each pagan god in order to make correct restorations. Just as a sculpture lacking attributes sometimes made it difficult for a restorer to accurately determine the identity of some mythological figures, adding an incorrect attribute could change the identity of the figure in the sculpture. Baroque restorers also needed to study the proportions of the surviving ancient fragments so the new pieces they were making would match. Pins (sometimes made of lead) and clamps held blocks of marble together; these bits of hardware had to be concealed to keep up the illusion that the sculpture was anything less than “complete.”

Ludovisi Ares, Pentelic marble, Roman copy after a Greek original from c. 320 B.C.E. with some restorations in Cararra marble by Gianlorenzo Bernini, 1622 (Museo Nazionale Romano di Palazzo Altemps; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Ludovisi Ares (detail), Pentelic marble, Roman copy after a Greek original from c. 320 B.C.E. with some restorations in Cararra marble by Gianlorenzo Bernini, 1622 (Museo Nazionale Romano di Palazzo Altemps; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Restoration was a serious subject according to Boselli, and it was not for second-rate artists. But Boselli’s ideal restorer was largely a fantasy—restoration was a way for Baroque sculptors to make ends meet, whether or not they had the talent to carry out the work as carefully as Boselli outlined.

Boselli’s praise for a restoration by Bernini, the Ludovisi Ares, is surprising. Boselli generally disliked the famous sculptor as well as the type of overtly Baroque elements that Bernini inserted in the Ludovisi Ares: the head and arm of the small Eros (Cupid) who playfully peeks out from behind Ares’ outstretched leg; and the hilt of the sword, with a human-like face with a wide open mouth that recalls Bernini’s bust of a Damned Soul, one of Bernini’s own self-portraits.

The ancient portions of the Ludovisi Ares were made from Pentelic marble from Greece, while Bernini’s restorations used Carrara marble from Italy. These marbles are different colors, which makes it easy to tell where repairs were made. Bernini was a highly skilled sculptor, and this was no accident. It was a choice.

Bernini brought an ancient work into his era with the clear intention of updating it for his own generation. He was quite capable of restoring in a conservative manner had he, or his patron, wished. Boselli’s praise for Bernini’s restoration of the Ludovisi Ares suggests that even a staunch advocate for more conservative restorations could be impressed with the fusion of both the classical and the Baroque. Although Boselli was in favor of authenticity, not all Baroque sculptors agreed.

A Return to Antiquity?

Nicolas Cordier, The Gypsy Girl (La Zingarella), early 17th century, marble and bronze, 140 cm high (Galleria Borghese)

Some of the most dramatic restorations undertaken in the 17th century were made for Cardinal Scipione Borghese by Nicolas Cordier. Look closely at the The Gypsy Girl (La Zingarella). The exotic elements—colored marbles and gilded bronze accessories—are restorations that hide a fragment of a draped woman (probably something like the Roman Herculaneum Women). The Gypsy Girl (La Zingarella) is clearly an early modern invention. Cordier’s restorations exhibit a taste that stands in opposition to Boselli’s view that restoration should complement the original sculpture.

In another restoration for Cardinal Borghese, Bernini added a pillow and mattress to the classical Sleeping Hermaphrodite, which depicts a figure with both masculine and feminine sexual characteristics reclining horizontally. Bernini’s restoration for Cardinal Borghese did not make drastic changes to the pose or figure. As seen in the Ludovisi Ares; Bernini’s restorations are something neither wholly classicizing nor wholly Baroque.

Sleeping Hermaphroditos, Roman copy of a Greek original from the 2nd century C.E. (Louvre) (photo: Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Bernini’s restoration received mixed reviews in the following century. French writer Charles de Brosses noted that to “pass one’s hand over it [the mattress], it is no longer marble, it is a real mattress of white leather or of satin which has lost its sheen.” For de Brosses, the mattress was a positive addition, encouraging someone to want to reach out and touch it. Yet, Francesco Milizia was appalled; he thought the mattress looked as if it had been filled with rocks.

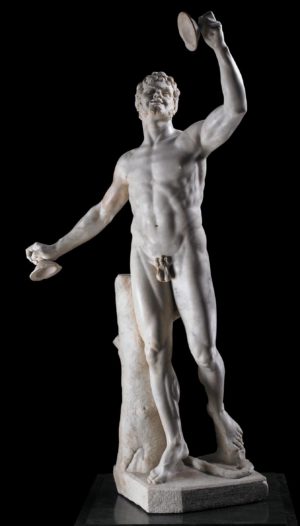

Rondanini Faun, torso and right thigh antique; extensively restored or “completed” during the Baroque by François Duquesnoy, c. 1625–30 (The British Museum)

To De-Restore or Re-Restore?

In the early 20th century, many ancient sculptures that had been restored in early modern times (such as the Apollo Belvedere), had their restorations removed. Beginning in the late 20th century, there has been a growing awareness of the impact that restorations had upon the understanding of a particular work of art. In some cases, restorations that were removed in the early 20th century for the sake of greater “accuracy” have been returned.

One of the most interesting examples of de-restoration occurred early on: when the “real” ancient legs of the Farnese Hercules were discovered, and the replacement legs made by Guglielmo della Porta, a student of Michelangelo, were removed. Today, della Porta’s legs can still be seen in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, no longer on the sculpture, but mounted in a case nearby.

While many 20th century art historians and conservators did not look fondly upon restoration efforts, the start of the 21st sees a renewed interest in the interactions between the early modern period and classical antiquity.

The British Museum’s Rondanini Faun consists of an antique torso and right thigh, while the remaining sculpture was created in the early 17th century by François Duquesnoy. The sculpture underwent conservation in 2004 and was then displayed as a product of the 18th century, rather than in the rooms allotted to the Greek and Roman collection. This acknowledges both the classical inspiration for the artwork, as well as the new meaning given by its restorer.