The Qutb archaeological complex: The Qutb complex and the Delhi Sultanate are important chapters in Indo-Islamic architectural history.

Read Now >Chapter 42

Cultural exchange and syncretism in the arts of South Asia since 1200

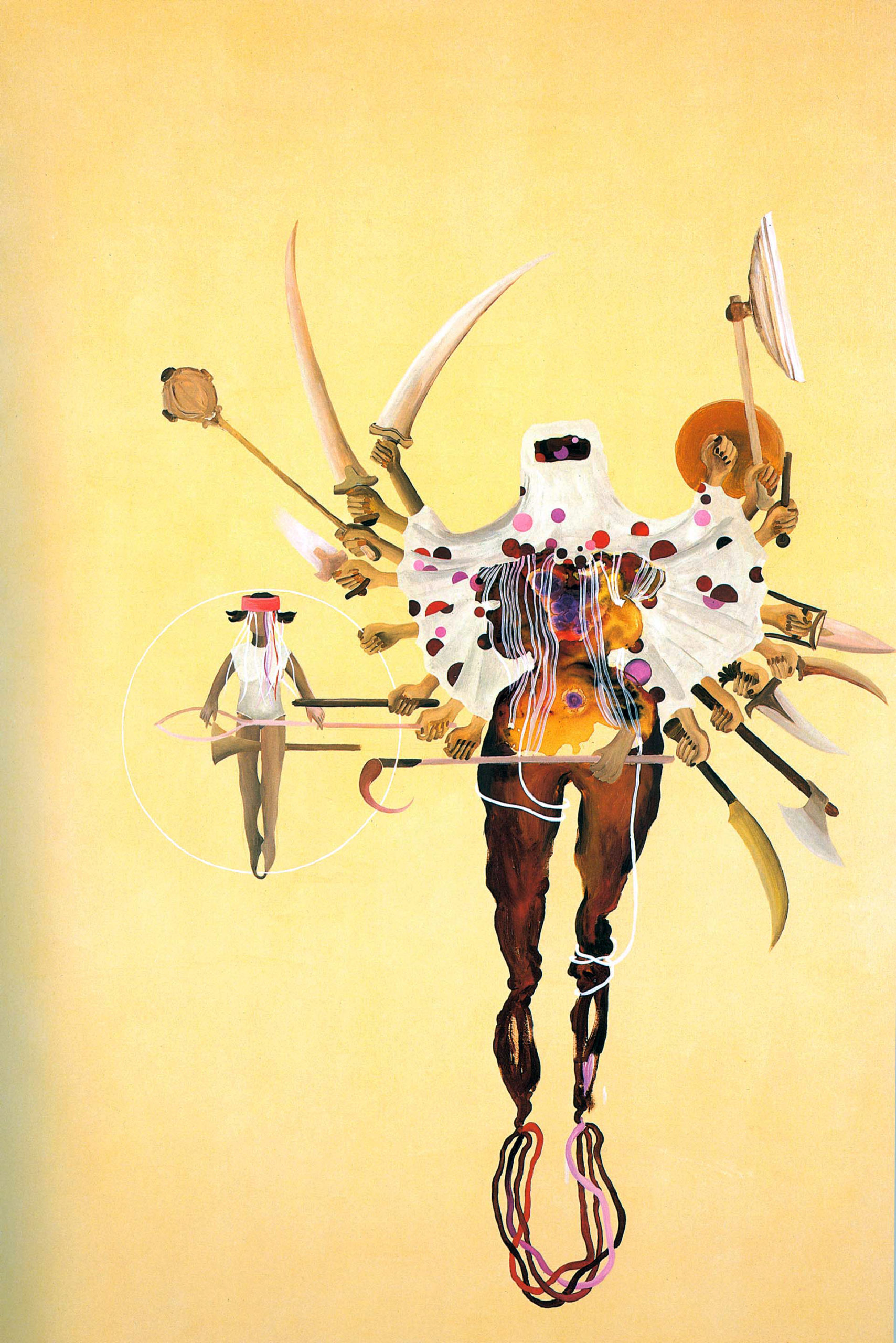

Shahzia Sikander, Fleshy Weapons, 1997, acrylic, dry pigment, watercolor and tea wash on linen, 243.8 x 167.6 cm

Contemporary artist Shahzia Sikander’s 1997 watercolor painting Fleshy Weapons depicts two partially nude figures suspended on an otherwise unadorned page. The larger figure appears to hold weapons in each of her 17 hands that are reminiscent of those wielded by the Hindu goddess Durga when she fights the buffalo demon Mahisha.

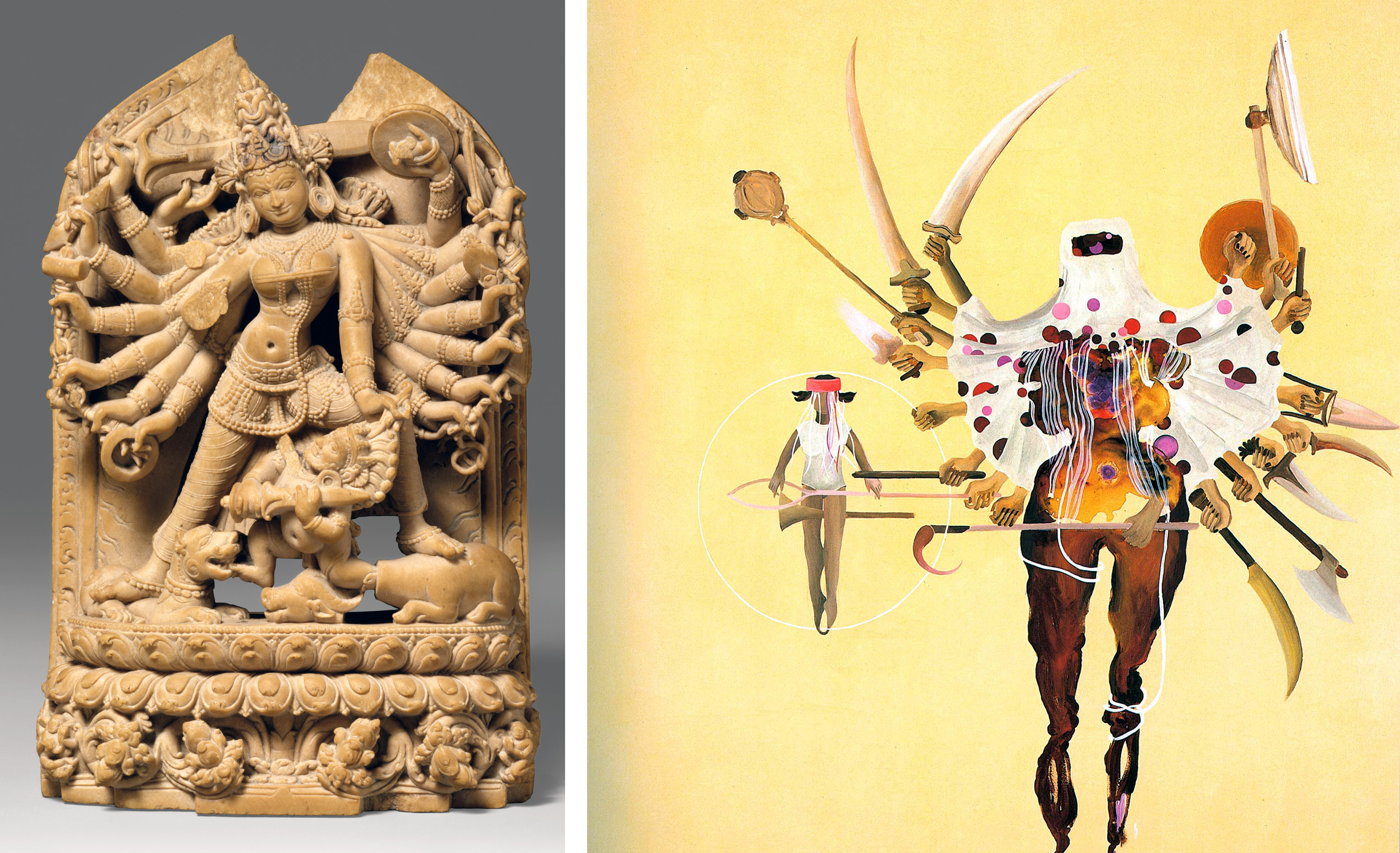

Sikander draws on the rich and diverse traditions of miniature painting in South Asia to create new meanings and subjects. Left: The Goddess Durga Slaying the Demon Buffalo Mahisha, 12th century (Bengal, or present-day Bangladesh or India), argillite, 13.5 x 8.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York); right: figure (detail), Shahzia Sikander, Fleshy Weapons, 1997, acrylic, dry pigment, watercolor and tea wash on linen, 243.8 x 167.6 cm

However, this figure is not Durga and her face is covered by a veil similar to a niqab that drapes over her shoulders and leaves only a small opening for her eyes. Sikander seems to be drawing on multiple visual sources from South Asia in the creation of this supernatural female warrior. She makes reference to Durga, the divine goddess prevalent in Hindu art and architecture, while at the same time alluding to veiling practices by some Muslim women in Sikander’s native Pakistan. As Sikander has said, the imagery in her work emerges through her interest in “subverting Hindu with Muslim and Muslim with Hindu,” in other words, dismantling distinctions between the two religions and highlighting shared cultural attributes and histories in South Asia across religious lines. [1]

Sikander’s work epitomizes a syncretic approach to art-making that is characteristic of much South Asian art across time periods. Syncretism is an important concept that is useful for understanding the diverse arts created in South Asia from roughly 1200 C.E. to the present. It refers to the blending of different cultural styles, forms, and ideas. This concept of blending different artistic styles to make something new appears throughout this broad period, irrespective of the ruling dynasty or powerful patrons who might have influenced the creation of a work of art at a particular time or place.

This chapter introduces examples of artistic syncretism in South Asia as a way to better understand the confluence of cultural forms, ideas, and influences that have shaped art and material culture from the Indian subcontinent.

South Asia (underlying map © Google)

Islam and Islamicate Art in South Asia

Qutb Minar, begun c. 1192–93, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: lensnmatter, CC BY-2.0)

A fundamental cultural shift occurred in South Asia at the end of the 12th century, the repercussions of which are still important today in many of the contemporary nations of the region (such as Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan). Muslim rulers from the west moved into South Asia and introduced Islam to the Indian subcontinent in 711, but it was not until the 12th century with the arrival of the Ghurids that Islam became a cultural force in South Asia. Prior to the introduction of Islam in South Asia, the region was home to the indigenous religions of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. With Islam came new forms of art and architecture, such as:

- manuscript painting on paper (rather than on palm leaf)

- true round arches and domes (rather than corbelled versions)

- entirely new building types such as mosques and tombs.

These materials and forms were prevalent throughout the Islamic world but were new to South Asia. Artists working for the new Muslim patrons of the region also drew on existing motifs and styles connected with the existing religions of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism. The results of this dynamic cultural exchange were new forms of artistic practice that not only changed the landscape of South Asia, but also affected the arts of the greater Islamic world.

This photograph depicts the courtyard of the (now ruined) Quwwat-al-Islam mosque at the Qutb archaeological complex in Delhi, a site which epitomizes artistic syncretism. In the foreground of this photograph we see the pillars of a colonnaded walkway created by reusing stone blocks that were once in local Hindu and Jain temples. In the distant background in the center is a c. 4th–5th century iron pillar. Like the stones of the colonnaded walkway, the iron pillar was also taken from an existing Hindu temple. By contrast, the arched screen and prayer hall that appear in the distance of the photograph illustrate the new architectural style of true arches introduced by the Muslim patrons who created this mosque. The courtyard of the Quwwat-al-Islam mosque, c. 1192, Qutb archaeological complex, Delhi (photo: Indrajit Das, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Qutb Complex illustrates the syncretism that characterizes the advent of Islam in South Asia. This important work of architecture was commissioned by the Ghurid military commander Qutb al-Din Aibak who conquered Delhi in 1193 and initiated the period of Muslim Sultanate rule. Artists working on the Qutb mosque strategically used spolia from destroyed Hindu and Jain temples in the area to create the open colonnades of the mosque. The exchange of cultural and artistic ideas flourished under the Sultanates as they expanded outside Delhi and established regional kingdoms throughout the subcontinent.

The “Lotus Mahal” is two-story pavilion that integrates design elements from temple architecture (the base, roof, and some stucco decorations) with features of Islamicate structures. This structure probably functioned as a reception hall or meeting place for the emperor and his advisors. “Lotus Mahal” in the city of Vijayanagara (present-day Hampi) in the state of Karnataka in India, 16th century (photo: Maheshwaran S, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Map of the Vijayanagara Empire (map: Mlpkr, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Syncretism also emerged in Hindu kingdoms of the region, such as in the Vijayanagara Empire’s capital city of Vijayanagara (present-day Hampi), in which the rulers strategically borrowed modes of dressing and language from Muslim-ruled kingdoms to their north. Scholars use the term Islamicate to describe this practice of drawing on the artistic and cultural attributes of Islam (different from an adherence to the religion itself). [2] For example, while the Hindu rulers of the Vijayanagara Empire patronized great Hindu temples and commissioned images of gods and goddesses, they also, at times, dressed in the attire of Muslim rulers or sultans who controlled the kingdoms north of Hampi. By presenting themselves as “Sultans among Hindu kings” they were acknowledging the power of the new cultural force of Islam. [3]

Read more about Islam and Islamicate art in South Asia

Sultanate art and architecture, an introduction: Mosques, tombstones, textiles, and murals are only a few examples of the art and architecture created on the Indian subcontinent in the sultanates.

Read Now >

Art and architecture of the Vijayanagara empire (1336–1646): Vijayanagara was the largest and most effective empire in pre-colonial south Indian history.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Syncretism, new religions, and diverse patronage

Indian Ocean Trade Routes (underlying map © Google)

The late 15th century marks another key moment in the arts of South Asia as new, syncretic forms emerge with the arrival of European merchants to the subcontinent and their involvement in the already robust Indian Ocean trade. Christianity becomes another important religious movement in the region. Jesuit missionaries from Portugal are some of the first Europeans who sought to produce works of art and architecture to proselytize and celebrate Christianity. Technically, Christianity had arrived much earlier, but it did not really take hold in terms of art and architecture until the Portuguese came to India in the 15th century.

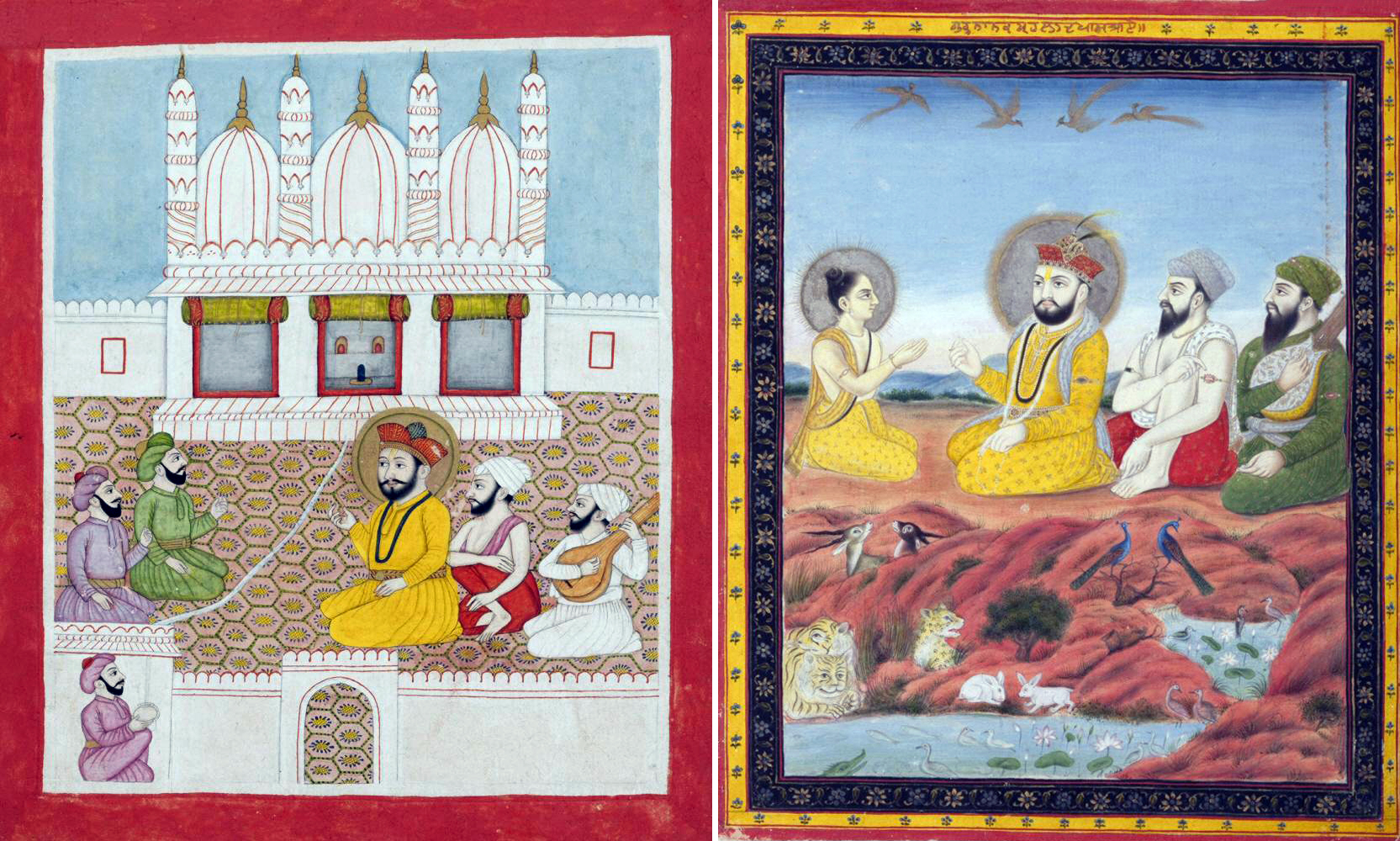

Two depictions of the founder of Sikhism. Guru Nanak converses with Muslim clerics (left) and Guru Nanak’s meeting with Praladh (right), from a manuscript of the Janam Sakhi (Life Stories), 19th century (India or Pakistan, Punjab region), opaque watercolors and gold on paper, 20.3 x 17.1 cm (left) and 20.6 x 17.1 cm (right) (Asian Art Museum, San Francisco)

Sikhism

Also during the 15th century, Sikhism emerges as a new religion that draws upon existing ideas and cultural forms developed through Hinduism and Islam. For example, an illustrated manuscript describing the life of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, depicts both real and imaginary meetings between Guru Nanak and spiritual leaders from other religions as a way to illustrate the diverse perspectives and insights that helped shape the core principles of Sikhism, a religion that centers on inclusivity and equality among people irrespective of their caste or gender.

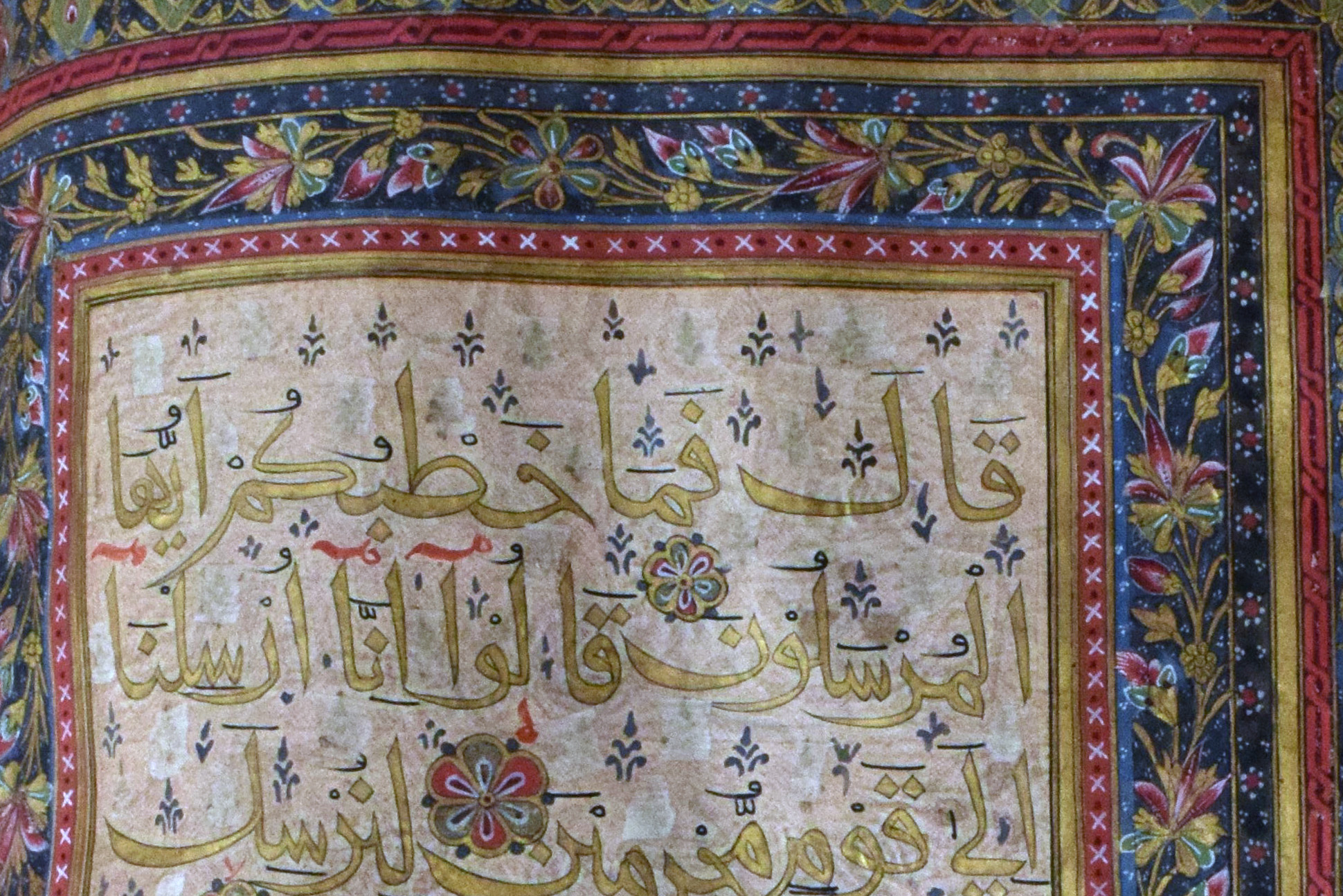

The artists of this manuscript depict Guru Nanak at the center of each scene, always wearing a yellow tunic and surrounded by a halo. In one image, Guru Nanak meets with Praladh, a renowned devotee of the Hindu god Vishnu. In another image, Guru Nanak travels to Mecca to meet with Muslim clerics. In the background behind the seated figures is the artist’s interpretation of the Ka’aba, the holiest shrine for Muslims and the focal point for all prayers. However, the artist had never seen the Ka’aba. Rather than depicting a cube-shaped structure covered in black cloth (as the Ka’aba actually appears), they imagined the shrine to look more like mosques or tombs in South Asia: made from white marble, flanked with minarets, and topped with multiple domes. The sacred black rock that is embedded in the Ka’aba is likewise misinterpreted as a black linga stone, comparable to what might appear in a Hindu temple.

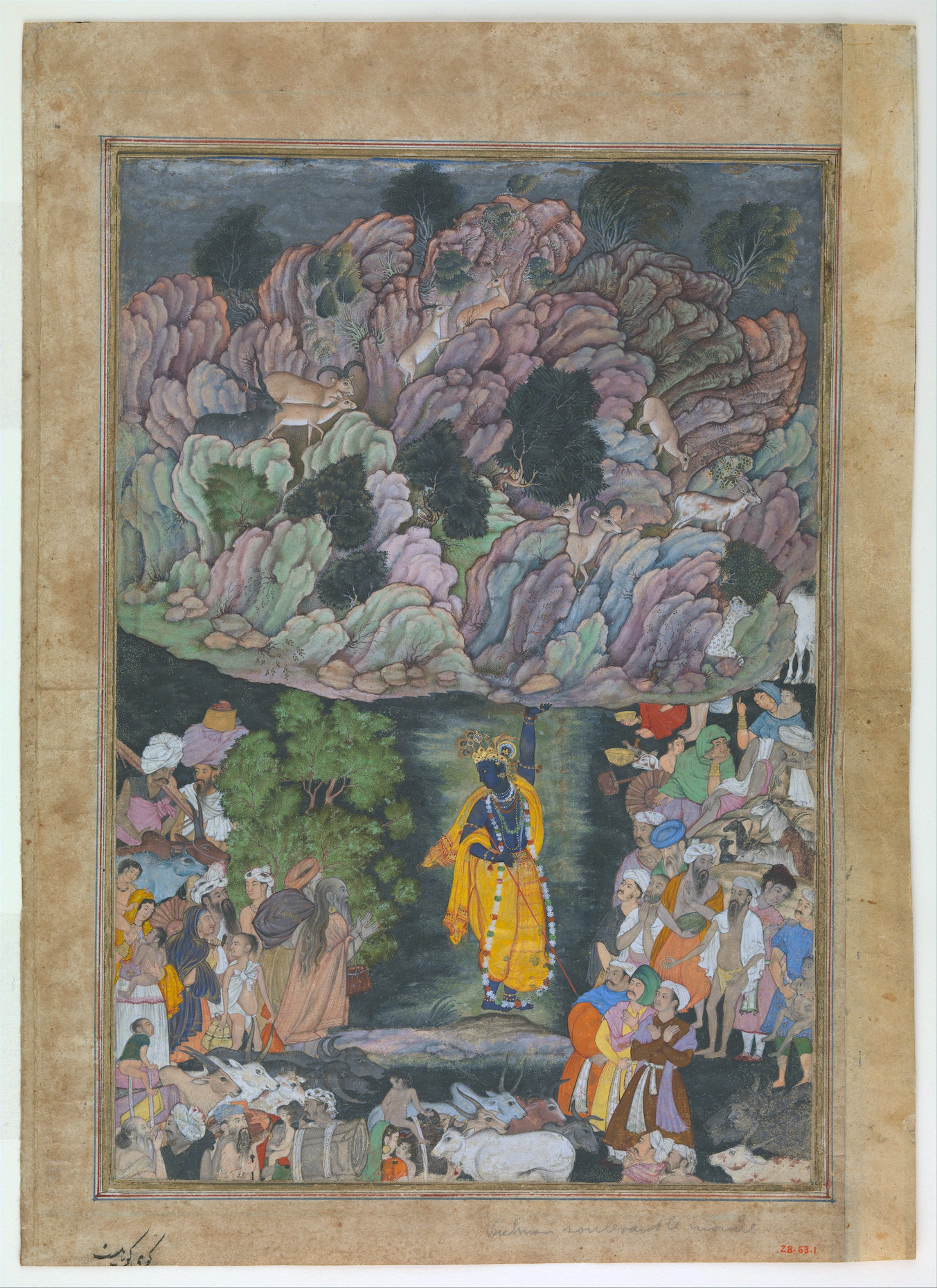

“Krishna Holds Up Mount Govardhan to Shelter the Villagers of Braj,” folio from a Harivamsa (The Legend of Hari (Krishna)), c. 1590–95 (Mughal period, attributed to present-day Pakistan, probably Lahore), ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper, 28.9 x 20 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Mughal period

By the 16th century, art and architecture in South Asia were dominated by the patronage of the great Mughal kings (also known as Timurids), powerful Muslim rulers who initially established their capital in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent but whose cultural influence spread throughout the region. An example of artistic syncretism during the Mughal period is a page from a Harivamsa manuscript, which recounts the stories of the Hindu god Krishna (also known as Hari). In this painting we see Krishna lifting Mount Govardhana to shelter the villagers of Braj from a storm sent by the god Indra. This image of a Hindu deity was commissioned by a Muslim ruler, the Mughal emperor Akbar, and translated from Sanskrit into Persian, the latter of which was the language of the Mughal court. The desire to commission a manuscript about a Hindu god further illustrates the intellectual curiosity and openness that characterized the Mughal emperor’s reign.

Company School and beyond

During the period of British rule in South Asia, which began with the presence and increasing power of the British East India Company (1600–1858) and was followed by British imperial rule (also known as the British Raj, from 1858–1947), syncretic art and architectural styles proliferated as both British and Indian patrons commissioned new buildings that drew on multiple forms and precedents. “Company School” paintings are one example of this artistic syncretism. “Company School” is a general term used to describe the diverse artistic output of Indian artists who produced work for British patrons, many of whom were affiliated with the British East India Company in India. In these paintings, artists often mixed styles and subject matters, drawing inspiration from both Europe and India.

Dip Chand, Portrait of East India Company official (likely William Fullerton), c. 1760–64 (Murshidabad, India), opaque watercolor on paper, 26.2 x 22.6 cm (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

A c. 1760 “Company School” painting by artist Dip Chand suggests that syncretic approaches informed even the lifestyles of the British living in India during this time. Here we see William Fullerton, an officer of the British East India Company who became the mayor of Calcutta in 1757, seated in a courtyard in a manner similar to that of an Indian prince. The floral carpet and bolster pillow that he leans upon, the attendants who stand behind him holding fly whisks, and the hookah that he smokes, are all reminiscent of painted depictions of Indian royalty. However, unlike comparable Rajput and Mughal paintings of royal figures smoking in a courtyard, Dip Chand’s painting of William Fullerton employs stylistic modes characteristic of “Company School” paintings: there is minimal depiction of landscape or setting and instead the focus of the painting is on the bodies of the figures. Dip Chand effectively draws the viewer’s eyes toward William Fullerton in particular, whose red coat and black hat and shoes make him stand out in contrast to the attending figures who are dressed entirely in white.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Mumbai, begun 1878 (photo: Dikshagusain718, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In addition to paintings, the “Indo-Saracenic” style—a blend of elements from Buddhist, European Gothic, Hindu, Mughal, and Sultanate architectural forms—was particularly popular in the 19th century and appears in such structures as the Amba Vilas Palace in Mysore, the High Court of Tamil Nadu in Chennai, and the Shivaji Terminus in Mumbai. While the British introduced European artistic styles and cultural forms into South Asia (including the dominant use of the English language), they were also keenly interested in the study of indigenous art and architecture and even emulated modes of kingship that were prevalent in South Asia—much like we see in Dip Chand’s portrait of William Fullerton as an Indian prince.

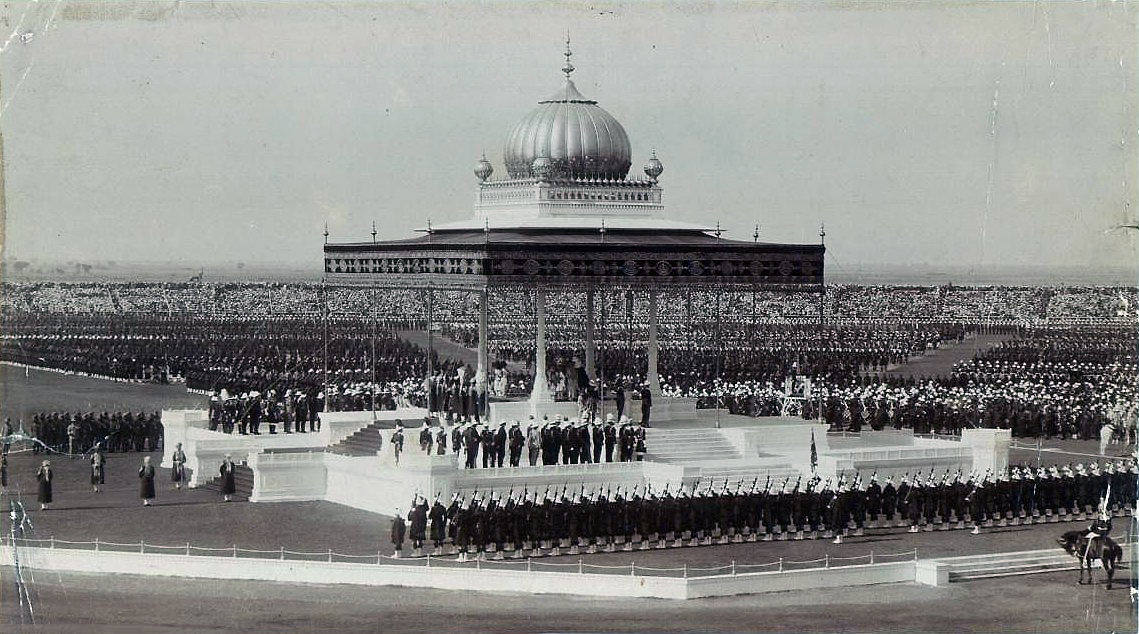

Delhi Durbar of 12 December 1911, with King George V and Queen Mary seated upon the dais (photo: CC0)

The so-called “Delhi Durbar,” a ceremony held by the British Raj to declare the succession of different British monarchs, presents yet another clear example of the desire for the use of syncretic cultural forms during this period: the British Raj modeled their imperial rule of India on earlier Mughal and Rajput displays of royal power by holding a formal court assembly or presentation of the monarch, known as a darbar. A photograph from the 1911 Delhi Durbar shows the British monarchs, King George V and Queen Mary, standing on an ornate domed dais and surrounded by rows of soldiers as they declare their new roles as Emperor and Empress of British India.

Palampore, c. 1725–50 (Coromandel Coast), painted and dyed cotton chintz, 226.4 x 285.5 cm (Victoria & Albert Museum, London)

There are numerous examples of textiles that were created during the period of British presence in South Asia that exemplify the idea of syncretism. For example, cotton bedcovers such as this one made along the Coromandel Coast (southeastern part of India) and known locally as palampores, were popular among European consumers. Indian textile artists used sophisticated techniques of mordanting and hand-painting and printing resists (such as wax or mud) and dyes, to achieve the intricate tree and floral designs on this textile. The floral garlands and fern-like tendrils that adorn the border of this palampore recall baroque-style textile patterns found on luxury silk interior fabrics made in Britain and France during the 17th and 18th centuries. However, the serpentine tree that dominates the center of the cloth draws upon entirely different visual referents: the fantastical floral forms that burst from the tree’s slender branches as well as the rocky mound near the base of the trunk are inspired by Chinese decorative arts. However, instead of taking direct inspiration from objects from China, the Indian textile artists responsible for creating this palampore, likely used European-made Chinoiserie (Chinese-inspired) designs as their source. The result is a unique, hybrid style that fuses European, Chinese, and Indian motifs and patterns into a new aesthetic.

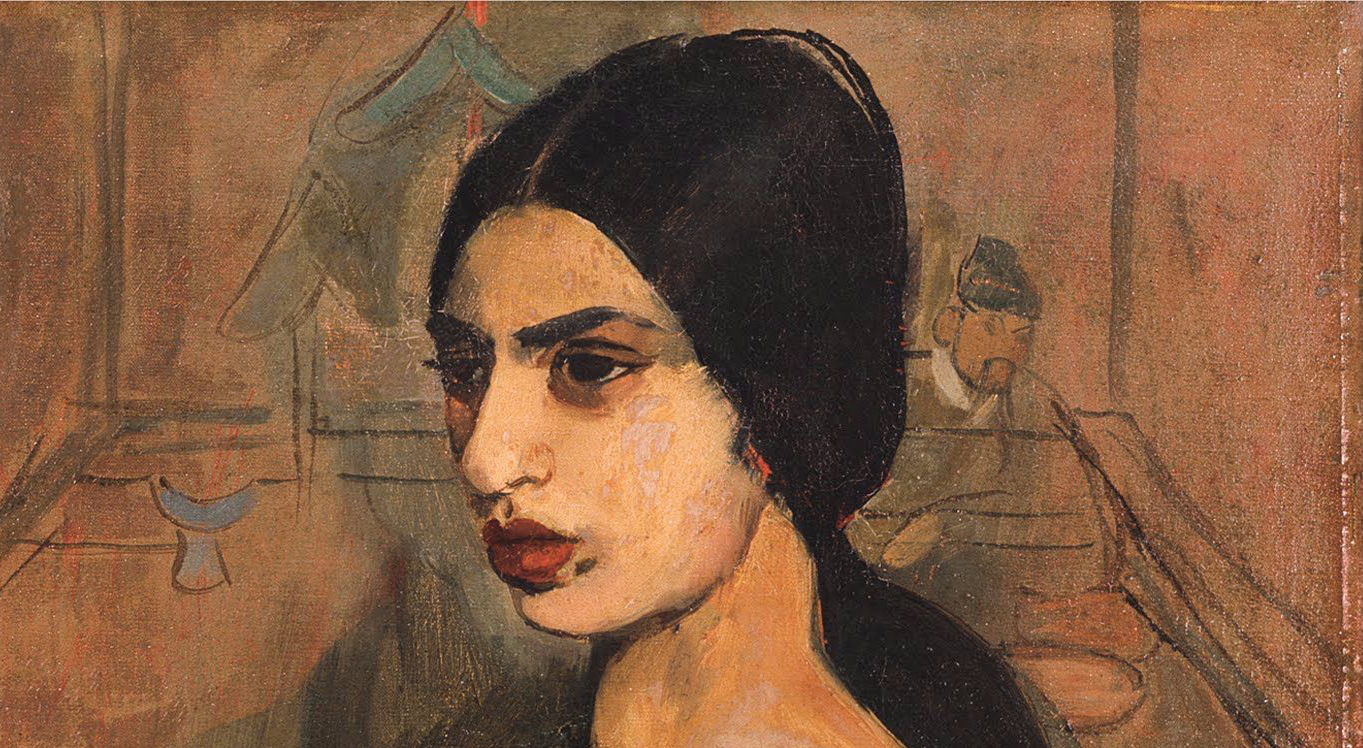

Artists like Raja Ravi Varma and Amrita Sher-Gil experimented with blending both European and Indian artistic styles and subject matter. While their personal backgrounds and art historical legacies are quite different, their syncretic approaches to art-making were effective in exploring hybridity and cross-cultural interactions as well as forging new aesthetic modes that have had lasting influence on modern and contemporary artists.

These are just a few of the many examples of syncretism in the arts of South Asia. Such objects and sites highlight the role of diverse voices, religious pluralism, and new perspectives that continue to shape the work of artists from this region.

Read essays and watch a video about syncretism, new religions, and diverse patronage

“Krishna Holds Up Mount Govardhan to Shelter the Villagers of Braj”: from a manuscript that reveals the many sources for artists in this period.

Read Now >

Indo-Portuguese ivory statuettes: Goan sculptors created images of the divine in ivory that are at once Catholic, European, and South Asian.

Read Now >

F. W. Stevens with Sitaram Khanderao and Madherao Janardhan, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, Mumbai: With its muted Indic features, the Chattrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus embraces an eclectic Gothic style that is a valuable example of the Indo-Sarascenic.

Read Now >

Cashmere shawls: For centuries, handwoven cloth from the Kashmir region of the Indian subcontinent has been revered for its exquisite softness and decorative surface patterns.

Read Now >

Containers of confluence: Consider imagery on painted and printed textiles from the subcontinent.

Read Now >

Imperial splendor: Opulent textiles were leveraged by kingdoms and empires to affirm their place in society while also revealing deep societal imbalances.

Read Now >

Raja Ravi Varma, A Galaxy of Musicians: One of Ravi Varma’s most famous paintings, he depicts 11 Indian women who appear to be in the midst of an elaborate musical performance.

Read Now >

Amrita Sher-Gil, Self-Portrait as a Tahitian: Sher-Gil engages with the artists Gauguin and van Gogh in her complicated self-portrait.

Read Now >/8 Completed

Notes:

[1] Shahzia Sikander in Art in the Twenty-First Century, season 1, episode 4, “Spirituality,” Art21 (2001).

[2] For more on the concept of Islamicate in South Asia, see Catherine Asher and Cynthia Talbot, India Before Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

[3] Philip Wagoner, “‘Sultan Among Hindu Kings’: Dress, Titles, and the Islamicization of Hindu Culture at Vijayangara,” The Journal of Asian Studies, volume 55, number 4 (November 1996), pp. 851–80.

Key questions to guide your reading

What are some of the different religions and cultural practices that are important or influential in South Asia during this period?

How do artists convey the experience of living in diverse, pluralistic societies?

In what ways do syncretic works of art and architecture create new aesthetic forms?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat are some of the different religions and cultural practices that are important or influential in South Asia during this period?

How do artists convey the experience of living in diverse, pluralistic societies?

In what ways do syncretic works of art and architecture create new aesthetic forms?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Learn more

Indian Block-Printed Textiles in Egypt: The Newberry Collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Interview with Shazia Sikander

Catherine Asher and Cynthia Talbot, India Before Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Mildred Archer, Company Paintings: Indian Paintings of the British Period (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1992).

Rosemary Crill, Chintz: Indian textiles for the West (London: V&A Publishing, 2008).

Vidya Dehejia, Indian Art. Art and Ideas (London: Phaidon, 1997, 1998, 2000).

Thomas Metcalf, An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain’s Raj (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989).

Philip Wagoner, “‘Sultan Among Hindu Kings’: Dress, Titles, and the Islamicization of Hindu Culture at Vijayangara,” The Journal of Asian Studies, volume 55, number 4 (November 1996), pp. 851–80.

Stuart Cary Welch, Room for Wonder: Indian Court Painting during the British Period, 1760–1880, exhibition catalogue (New York: American Federation of Arts, 1978).