The ruins of Vijayanagara empire, the Achyutaraya temple ruins, 16th century (photo: Arunjayantvm, CC BY-SA 4.0)

For little more than two centuries, the Vijayanagara empire dominated the political and cultural landscape of medieval-period south India. Founded in 1336 C.E. by former chieftains of the Delhi sultanates who had invaded peninsular India, Sangama brothers Harihara I and Bukka I established their newly created kingdom along the Tungabhadra River in the Deccan plateau region and called their fortified capital, Vijayanagara or “City of Victory.”

Using their diplomatic and military skills, Vijayanagara kings protected their kingdom against invasions from their northern neighbors—the Bahmani Muslim sultanates and Gajapati Hindu rulers—enabling them to reign over much of southern India. Regional governors (nakayas) exercised authority as their agents since territories extended beyond the Kannada and Telugu areas to encompass the Tamil region farther south. Although the capital city—also called Vijayanagara—was located inland, kings encouraged overseas trade from coastal ports that transported local goods for the international market but monopolized control in the trade of warfare items such as war animals (horses and elephants) and weapons. Accumulated wealth allowed the Vijayanagara monarchs to sponsor art and literature in their capital and throughout their empire. In their travel accounts, Portuguese, Italian, and Persian visitors described Vijayanagara as a prosperous and well-planned city with irrigation technology, bustling bazaars, a large standing army, and sumptuous palaces, even comparing it to Rome.

Vijayanagara rulers promoted the Hindu religion by building several religious buildings and supporting extravagant religious festivals at the capital. The most famous and successful sovereign, Krishnadevaraya was a great patron of architecture and literature, and an accomplished poet himself. During his reign, the kingdom reached the pinnacle of its fame, glory, and size.

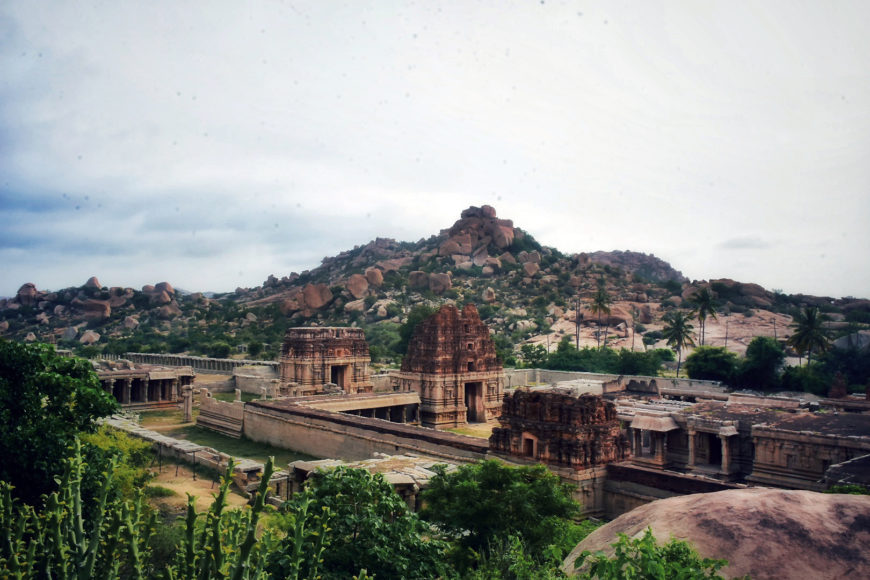

The ruins of Vijayanagara empire in the boulder strewn landscape of Hampi (photo: Ksuryawanshi, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The capital of the Vijayanagara Empire

Muslim armies sacked the city in 1565, after the Vijayanagara army lost a major battle, and the capital was abandoned. The court shifted to the fortified cities of Penukonda and later Chandragiri (both in the present-day state of Andhra Pradesh), where the much-reduced, much-weakened kingdom remained until the empire’s end in 1646. The ruins of the extraordinary imperial site (present-day Hampi in the state of Karnataka in India are still visible today, where numerous structures, both standing and fallen, dot the rugged, semi-arid landscape of granite boulders, hilly terrain, and river plains.

There are over 1,600 surviving monuments in the capital city Vijayanagara, covering 4,187.24 hectares (16 square miles) divided into three general zones:

- a fortified urban core, which included a royal center,

- a sacred center consisting of temples and shrines, and

- the suburban settlements.

This is the north tower in an enclosure.

The fortified urban core

Natural rock barriers as well as built military fortifications that included massive granite walls, watchtowers constructed of solid masonry, and looming gateways protected the kingdom from incursions.

A few surviving buildings in the royal center within the urban core give a sense of the private residential area of the royal household and the various sectors connected to the administrative, ceremonial, and military duties of the Vijayanagara rulers.

The “Queen’s Bath”

Interior of the “Queen’s Bath,” c. 15th–16th centuries, the city of Vijayanagara (photo: Shivajidesai29, CC BY-SA 4.0)

A water pavilion, intended for bathing (commonly identified today as the “queen’s bath”), is a large square building with a plain exterior with a multi-lobed arched doorway, but an elaborate, open-air interior containing pointed arches, plaster-decorated domes and vaults, and corridors with projecting balconies that surround an interior pool. Royal members probably used it as a private bathing chamber or a cool resting place.

This structure, like other secular buildings at the imperial site, creatively combines architectural and decorative components of Islamicate architecture, such as the arched forms (that can be seen on the interior and exterior), with Hindu-derived elements, such as the foliated brackets shaped as lotus buds (on the interior only, they are the supports below each “window”) that are unique to the Vijayanagara kingdom. This combination of architectural elements demonstrates that Hindu culture was deeply transformed by its contacts and interactions with Islamic culture during this time period—as do other buildings, including the “Lotus Mahal.”

The “Lotus Mahal”

The “Lotus Mahal,” the modern-day name for the two-story pavilion that integrates design elements from temple architecture (the base, roof, and some stucco decorations) with features of Islamicate structures, probably functioned as a reception hall or meeting place for the emperor and his advisors.

It boasts openings with multi-lobed, recessed arches, plastered decorations supporting vaults and domes, and a stepped, pyramidal roof capped with temple-like finials. The cusped arches, vaults of various designs, and the decoration in geometric and foliated motifs on the walls and ceilings reflect an Islamic character, while the base, the multi-layered roof design, and stucco ornaments exhibit an Indic temple style. This stylistic adoption suggests further evidence of a vibrant exchange between Turko-Persian and Indic cultures and a fervent desire to participate in the larger cosmopolitan culture beyond Vijayanagara’s imperial borders.

Elephant stables

The most monumental of all courtly structures at the capital are the elephant stables that housed the ceremonial elephants used by royalty. The stables only accommodated elevan elephants (or twenty-two, if two were placed inside) and the Vijayanagara army would require many more. In front, the open space could have been a parade ground.

Built of solid masonry decorated in stucco, this building consists of eleven large chambers, whose domed chambers, arched doorways, and side vaults reveal an Islamic influence and the double-story pavilion at its center evokes the design of Indian temples. The arches look similar to architectural features common in the Bahmani sultanate, such as at the Jami Masjid in Gulbarga, Karnataka.

Royal platform

A great platform dominates the royal center. Horizontal bands of low relief friezes depict various facets of courtly life (such as the procession of war animals, hunting scenes, warriors in martial activities, women performing folk dances with sticks, and musicians) surround this multi-story stone stage.

Reliefs on the west end of the south face of the royal platform in the city of Vijayanagara. From top to bottom: 1) royal elephants; 2) camels, musicians, and dancers; 3) horse-riding warriors; 4) hunting scenes; 5) a king reviewing his infantry and cavalry (photo: Vipulvaibhav5, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Because the king would sit atop the platform to witness the royal festivities, religious rites, and entertainment associated with the Mahanavami festival, an important annual event at the capital, this tiered platform is usually known as “Mahanavami Dibba” (House of Victory). Mahanavami refers to the last day of the Hindu festival Navratri when the goddess Durga defeated the buffalo-demon Mahishasura. Vijayanagara rulers worshipped Durga for strength to conquer their foes before embarking on their military campaigns. The last panel of the reliefs depicts the king inspecting his army before one of his campaigns.

Royal platform

Water tanks

Water tank near the royal platform, 15th century, in the city of Vijayanagara (photo: Ms Sarah Welch, CC BY-SA 4.0)

A large water tank (pushpakarni), close to the Mahanavami Dibba and square in shape, encompasses multiple steps in a semi-pyramidal configuration of black schist stone leading down to the next level. Its configuration allowed people to easily get in and out of the water. Fed by the nearby Tungabhadra River through an aqueduct system, the reservoir was probably used by royal members for ritual bathing and cleansing before prayers, or for the immersion of metal embodiments of deities during religious ceremonies.

Ramachandra temple

Rectangular enclosure at the Ramachandra temple depicts within horizontal bands processions of elephants, horses, armies, and dancers during the Mahanavami festival, in the city of Vijayanagara. Left: the enclosure (photo: Ravibhalli, CC BY-SA 3.0); right: detail of the processions (photo: Soham Banerjee, CC BY 2.0)

The fifteenth-century Ramachandra temple, dedicated to worshipping the divine hero-king Rama (one of the avatars of Vishnu), served as a small, private chapel for the Vijayanagara rulers at the center of the royal area.

The Vijayanagara kings not only viewed Rama as an ideal king, the site’s physical landscape itself is closely associated with the epic about Rama called the Ramayana: it is believed to be the monkey kingdom, Kishkindha where Rama arrives searching for his abducted wife Sita who dropped her ornaments there while being whisked away by the demon-king Ravana, where Rama meets with monkey army commander Hanuman and monkey king Sugriva to seek their help, and where Rama rests during the monsoon months before journeying to Lanka to rescue Sita. Images of Hanuman can be seen throughout the capital city, known as his birthplace. For his service and loyalty to Rama, Hanuman, depicted as an anthropomorphic monkey, exemplifies the ideal for human devotion (bhakti).

The richly carved rectangular enclosure at the Ramachandra temple includes horizontal bands that depict processions of elephants, horses, armies, and dancers during the Mahanavami festival (discussed above).

Temples outer walls with episodes from the Ramayana depicted, in the city of Vijayanagara (photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, CC BY 2.0)

Carved panels on its inner compound wall and temple’s inner and outer walls illustrate episodes from the Ramayana. For example, in one section of the inner wall, the reliefs seem to depict scenes from Aranya Kanda (“forest chapter”), the third book of the Ramayana, when Rama, Sita, and Lakshmana lived in the forest during their exile.

Temple’s inner walls with episodes from the Ramayana depicted, in the city of Vijayanagara (photo: Ms Sarah Welch, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In a scene from this book (the third panel in the middle row), Rama aims his bow at the demon Maricha who took the form of a golden deer.

Finely carved black stone pillars of the Ramachandra Temple, in the city of Vijayanagara (photo: Aravindreddy.d, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Four pillars of polished black limestone inside the temple have ornate sculptured blocks, chiseled with bas reliefs, primarily of Vishnu’s many incarnations. Vishnu is the Hindu god who represents preservation in the universe. Having many different forms, Vishnu is shown as a god or as one of his ten incarnations—beings that exist on earth—called avataras: Matsya (fish), Kurma (tortoise), Varaha (boar), Narasimha (half-man/half-lion), Vamana (dwarf), Parasurama (warrior with an axe), Rama (prince/king of Ayodhya), Krishna (foster-son of Yashoda and Nanda), Buddha, and Kalki (destroyer of evil). Vishnu descended on earth in various forms to defeat certain demons in order to restore cosmic order.

Temples to Rama at this time are rare, only becoming slightly more popular during the post-Vijayanagara period. As mentioned earlier, the Vijayanagara kings seemed to view Rama as an ideal king. Although we do not know for sure, they may have viewed themselves like the divine hero-king Rama, given that the landscape and site was connected to the mythology, and building a temple here (which did not predate the site as did the Virupaksha temple, discussed below) may have been a way to articulate a political statement that established themselves as Rama incarnate.

The sacred center with sites (such as Vittala temple and Virupaksha temple) discussed in this essay (underlying map © Google)

Sacred center of Vijayanagara

The religious monuments at the capital’s sacred zone are temples on Hemakuta hill, the earliest of which are shrines devoted to Jainism, once the dominant religion in the region.

The Virupaksha temple

Virupaksha temple, with the gopura towering over the complex, in the city of Vijayanagara (photo: Saranya Ghosh, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The oldest Hindu shrine within the imperial site and still in active worship today is the Virupaksha temple, which predated Vijayanagara rule but was enlarged in 1509–10 for Krishnadevaraya’s coronation. Virupaksha, a form of god Shiva, was the patron deity of the Vijayanagara kings.

The enclosed temple complex has an east-facing, 160-foot high entrance tower (gopura); many Hindu temples face the direction of the rising sun, making the east side the typical entry for devotees. Annual festivals at the temple celebrate the marriage of Virupaksha with his consort, the local folk goddess Pampa, after whom the village of Hampi takes its name.

Left: The mandapa with a painted ceiling; right: scenes like the marriage of Pampa and Virupaksha (in the center), both in the Virupaksha temple, in the city of Vijayanagara (photos: Dineshkannambadi, CC BY-SA 3.0)

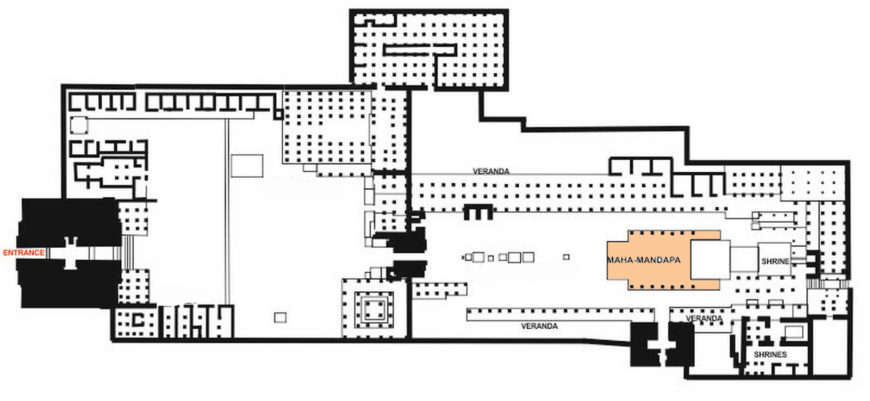

After you enter through the gopura, then walk through the courtyard of the temple complex, you eventually pass by long verandas until you reach the mandapa (pillared hall). Inside, paintings decorate the ceiling of the mandapa (see the diagram above for the mandapa‘s location). They are divided into rectilinear boxes of various sizes portraying narrative scenes, like the marriage of Pampa and Virupaksha, in which figures are shown with faces in profile, large frontal eyes, and narrow waists rendered in a color palette of red, light blue, and black. The representation of figures is typical of the time more broadly.

The marriage of Pampa and Virupaksha is a classic example of “Sanskritization” whereby the local folk goddess marries a pan-Hindu god. As a form of Parvati, Shiva’s wife, the local deity becomes assimilated into the wider Indian pantheon, and Shiva becomes a part of the local temple site.

Pavilions

Colonnaded bazaar street in front of the Virupaksha temple, Vijayanagara (photo: aakashlohia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In front of the temple are a series of pavilions lining both sides of the one mile-long road of what was once the center of flourishing trade; a thriving marketplace selling textiles, spices, gold and gemstones; and residences for the elite. In their reports about Vijayanagara, foreign travelers, traders, and visitors marveled at the presence of numerous merchants and affluent residents and at the variety and quality of commodities that had reached the cosmopolitan metropolis: the imperial capital gained from its lucrative trade with other lands and peoples.

The Vittala temple

Vittala temple complex as seen from outside, in the city of Vijayanagara (photo: Amlan Chakraborty, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The most magnificent monument at the capital in the sacred center is the Vittala temple, dedicated to a form of Vishnu. Dating to the fifteenth century, the complex, comprising the main temple and several subsidiary shrines, is set inside a rectangular court.

“Marriage hall” (kalyana mandapa), c. 15th–16th century, in the Vittala temple complex (photo: Dineshkannambadi, CC BY-SA 3.0)

An important component and a hallmark of Vijayanagara art is the open, multi-pillared “marriage hall” (kalyana mandapa) used for ceremonies involving the symbolic wedding of the temple’s deity to his consort. Comprising a raised platform surrounded by rows of massive, intricately carved granite columns, the hall exhibits external piers with riders on rearing yalis (mythical creatures) and elaborate brackets. Yalis were a common motif in south Indian temples since about the sixteenth century, and they depict a creature that is part horse, part lion, or part elephant, and who possibly functioned as protectors or guards since they are typically located at entries.

The novel feature of the temple is a stone chariot—a Garuda shrine that imitates a wooden chariot used to carry metal images of deities in procession during religious festivals. Garuda is the animal mount (vahana) of Vishnu, and as is common in temples, and faces the enshrined god. Immobile deities are found in the temple’s inner sanctum.

Vittala temple

Monolithic carvings

Monolithic sculpture of Narasimha, Lakshmi Narasimha Temple, in the city of Vijayanagara, over 20-feet tall (photo: BRK, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Taking advantage of the massive boulders scattered throughout the landscape around the city, large monolithic carvings can also be found at the site. For example, a spectacular rock-cut sculpture over twenty-feet tall, donated by Krishnadevaya (considered the greatest ruler of the Vijayanagara empire), represents Narasimha, the man-lion incarnation of Vishnu seated in a yoga position beneath a seven-hooded serpent (though is sometimes shown with five or ten-heads). In one of his incarnations, the serpent, called Adisesha, upon whom Vishnu is said to sleep, formed a seat for Narasimha.

Witness to the grandeur of an empire

Vijayanagara was the largest and most effective empire in pre-colonial south Indian history and the first southern Indian state to cover the three main linguistic and cultural regions (Kannada, Telugu, and Tamil) of this area. The impressive ruined capital today bears witness to the grandeur of an empire that ruled from that city, its position as a major population center, nexus of trade routes, and the extent that Islamic-inspired forms and practices altered Indic courtly life during the Vijayanagara period. Recognizing Vijayanagara’s significance, UNESCO designated the ruins at Hampi in Karnataka as a World Heritage Site in 1986.

Additional resources:

Asher, Catherine B. and Cynthia Talbot. India Before Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Fritz, John M., George Michell, and M. S. Nagaraja Rao. Where Kings and Gods Meet: The Royal Centre at Vijayanagara, India. Tuscon: University of Arizona, 1984.

Huntington, Susan L. The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain. New York: Weatherhill, 1993.

Lycett, Mark T. and Kathleen D. Morrison. “The ‘Fall’ of Vijayanagara Reconsidered: Political Destruction and Historical Construction in South Indian History.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 56, No. 3 (2013): 433-70.

Michell, George. The New Cambridge History of India 1:6 Architecture and Art of Southern India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Stein, Burton. The New Cambridge History of India 1.2 Vijayanagara. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre, “Group of Monuments at Hampi,” 2021.

Verghese, Anila. “Deities, Cults and Kings at Vijayanagara.” World Archaeology 36, No. 3 (Sep. 2004): 416-31.

Wagoner, Phillip B. “‘Sultan among Hindu Kings’: Dress, Titles, and the Islamicization of Hindu Culture at Vijayanagara.” The Journal of Asian Studies 55, no. 4 (Nov. 1996): 851-80.