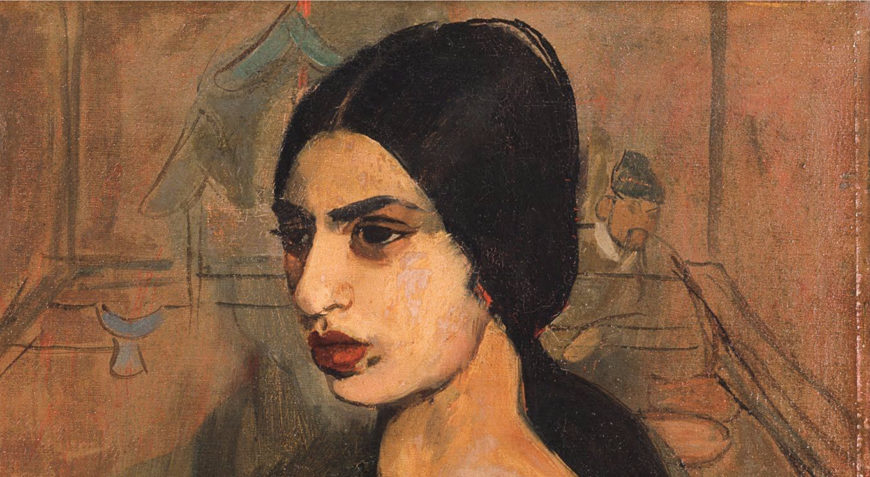

Amrita Sher-Gil, Self-Portrait as a Tahitian, 1934, 90 x 56 cm (Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi)

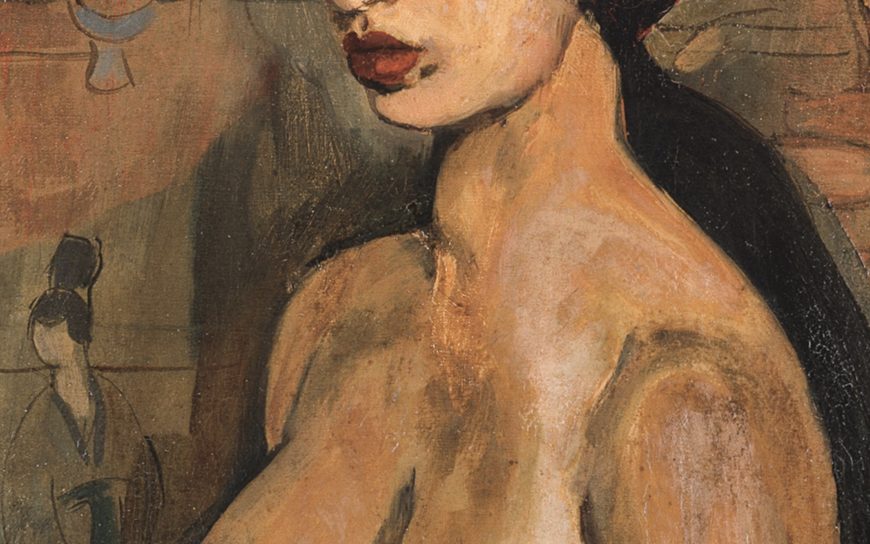

In a large self-portrait, the modernist painter Amrita Sher-Gil stands half nude with a plain white wrap around her waist. Her loosely tied jet-black hair, parted down the middle, flows down her back. Her brown skin is dappled in varied shades of ochre, nutmeg, and cinnamon, created with multiple layers of paint.

Her upright posture and her hands crossed in front of her convey a measured and firm stance. She turns to the side and gazes off into the distance, a pensive expression on her face, though she leaves us with no clear indication of what the subject of her ruminations might be.

In the background, we see a seated man and slender kimono-clad women occupying the interior or exterior of a pagoda-like structure. [1] Although the oblique angles of the walls give the impression of some spatial depth in this scene, the dramatic difference in scale between Sher-Gil and the other figures, as well as the presence of a large grey shadow cast in a frontal pose behind her, suggest that she does not inhabit the same space as the Japanese figures, but rather stands in front of a flat screen or wallpaper that is decorated with an Asiatic tableau.

In this challenging painting, Sher-Gil engages with the artists Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh and their entanglements with representations of non-European cultures in their individual quests to find their place within and actively shape the discourse of modernist art. It also speaks to her own multi-faceted identity and training as an artist.

Detail, Amrita Sher-Gil, Self-Portrait as a Tahitian, 1934, 90 x 56 cm (Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi)

Gauguin and cross-cultural entanglements

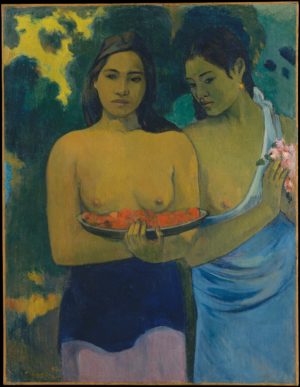

Paul Gauguin, Two Tahitian Women, 1899, oil on canvas, 94 x 72.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Sher-Gil’s painting, entitled Self-Portrait as a Tahitian, is a direct reference to the art of Gauguin who, like many other late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists adopted subject matter outside the European tradition (primarily the arts of the Pacific Islands and modern peasant culture in France). Embracing subjects he saw as “primitive” was, for Gauguin, a critique of traditional European painting and at the same time, a return to a perceived, more natural way of life in response to increasing industrialization. Artists like Gauguin were looking for a way to reinvigorate the language of modern art.

After Gauguin lost his job as a stockbroker in the French financial crash of 1882, he turned his focus to the arts. In search of new, exotic subject matter, he travelled to Panama, Martinique, Brittany, Arles, and finally the Pacific Islands. Inspired by the pictorial possibilities of these locations, he worked increasingly in a style of bold colors and simplified flat forms. Through his paintings, drawings, sculptures, and crucially his writings, he crafted a myth and a persona of a self-exiled Western observer and admirer of so-called “primitive” cultures. Gauguin famously and frequently sourced his imagery from reproductions, books, and postcards of scenic vistas, art, architecture, and artifacts from South America, India, China, Japan, Java, and Egypt.

Although Gauguin was disappointed to see the marks of French colonization during his travels to the South Seas in the 1890s, his paintings of the Polynesian Islands nonetheless perpetuated a long-standing Western myth of a utopia untouched by European influence. In his famed Two Tahitian Women, the figures entice the presumed male viewer with exposed breasts, pink blossoms, and a platter of mangoes, offering fantasies of a primeval Tahiti inhabited by exotic, sexually available Indigenous women.

Sher-Gil engages with Gauguin’s iconic Tahitian women. Like Gauguin, she also employs color for its affective and emotive qualities. In her painting, a Tahitian identity takes the form of an Indian body, with brown skin substituting for brown skin. Her monochromatic palette of terracotta shades helps to flatten the space, which is a pictorial strategy that was characteristic of modernist art. But the brown background also works to focus the eye on the artist’s body. If green and yellow tones were necessary for Gauguin to convey the “otherness” of the Tahitian women, then brown in all of its dynamic layers uncompromisingly confronts the viewer throughout Sher-Gil’s composition. As the color of the colonized body with its connotations of inferiority in Western culture, brown here is not alien, but prevalent.

Foreigner in Paris

Sher-Gil’s own biracial identity perhaps enabled her to masquerade as a Tahitian woman. She was born in 1913 in Budapest to a Hungarian-Jewish mother and a Sikh father, and moved with her family to Paris in 1929, where she studied art at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and later at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

Amrita Sher-Gil, Young Girls, 1932, oil on canvas, 134 x 164 cm (National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi, India)

She was an active participant in the city’s bohemian lifestyle, ingrained in its cultural and artistic social circles, and she found success in the art world. At the École des Beaux Arts, she won the first prize for the annual still-life and portrait competition every year for the first three years of her study. In 1932, she exhibited at the Grand Salon to many favorable reviews by art critics who remarked on the force and vigor of her work. The next year, she won a Gold Medal for her large-scale painting Young Girls, which was “the picture of the year,” and subsequently she was elected as an Associate of the Grand Salon, making her the youngest and the only Asian individual to have received this recognition.

However, as a foreigner, she never quite escaped her exotic status. The artist was described by a friend and art critic, Denise Proutaux, as “an exquisite and mysterious little Hindu princess” who “speaks French like a Parisian” and whose “blue silk sari brings out the amber and ochre skin that conjures up the mysterious shores of the Ganges.” [2]

Sher-Gil’s biographer Yashodhara Dalmia notes that the artist’s self-portraits from her Paris period (1929–1934) reflected her academic training, but also denoted a way to grapple with her Euro-Indian identity. The shadow behind Sher-Gil in the self-portrait—possibly a male onlooker with cropped hair and broad shoulders—might symbolize the looming influence of male modernists in the art world, like Gauguin and van Gogh. It might also suggest the hybrid roles which she has had to negotiate; she was both objectified as an exotic outsider figure while holding agency as a painter with the ability to portray herself as she desired.

Was Sher-Gil identifying with the position of women from the many regions that Europe had colonized, or was she making a more specific association between her body and the Tahitian nude constructed by Gauguin? Or was it more about the language of modernism itself as practiced by her forebearers than the actual nude that was of significance here? These layered possibilities combined with her evocative and not-easily-accessible disposition in the painting break with established tropes of representing colonized women as lacking intellectual depth and solely existing for the consumption of the male, Western viewer. Instead, her self-portrait is an expression of sophisticated ideas and individualism, evoking a desire for self-discovery that she saw in the work of Vincent van Gogh.

Van Gogh and the quest for self

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889, oil on canvas, 60 x 49 cm (Courtauld Galleries, London)

In her discussion of the nuances of Self Portrait as a Tahitian, art historian Saloni Mathur notes how unusual or improbable the Japanese background was for a Tahitian subject. It was an intentional bringing together of the formal elements of varied “exoticisms” that preoccupied artists of her time. Sher-Gil’s artistic training in Paris would surely have fostered an understanding of the Western fascination with the art of Japan in the later part of the nineteenth century (referred to as Japonisme). With an influx of Japanese art and design into Europe and America at this time, progressive artists adopted compositional devices, such as large areas of flat color, abrupt cropping, and oblique vantage points, as well as explored new subject matter, and reflected a deep admiration for the decorative arts found in the visual language of Japanese aesthetics.

Japonisme had an indelible impact on Western modernist art. Artists like van Gogh even became avid collectors of Japanese prints and readers of Japonisme literature of the day. In his Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, a Japanese woodblock print of women in traditional attire in a landscape with Mount Fuji can be seen behind the artist, which he had adapted from his own personal collection of prints that he pinned to the walls of his studio. Van Gogh believed Japanese people to be untainted by the corruptions of Western society.

Detail with Japanese figure on the right, Amrita Sher-Gil, Self-Portrait as a Tahitian, 1934, 90 x 56 cm (Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi)

Van Gogh’s infusion of his individual temperament and psychological state through markers of exoticism into his paintings may have partly inspired Sher-Gil’s own self-portrait. It should be noted that Sher-Gil’s Japanese figures are thinly painted and more sketchily rendered than the careful handling of paint that the artist dedicates to the representation of her own body. The architectural perspective lines of the walls are even visible through the body of the seated man suggesting that Sher-Gil was not as concerned with the individual details of the Japanese imagery, but rather wanted to convey her overall awareness of Japonisme’s crucial role in modernist practice, and more importantly draw an artistic lineage to van Gogh.

Sher-Gil never met Gauguin and van Gogh, who were decades removed from the young emerging artist. As Mathur argues, Sher-Gil related to van Gogh’s desire to foster an image of himself as an artist, while negotiating a relationship to a space outside of Europe via personal experiences and feelings of social displacement. Over the years, she grew to increasingly identify with van Gogh over Gauguin, even explicitly writing in a letter from 1937,

In spite of the fact that till now my special favorite has been Gauguin, I sometimes feel that van Gogh was the greatest of the two. [3]

But in Self-Portrait as a Tahitian, Sher-Gil’s engagement with the work and lives of both modernist precursors is palpable. Using their innovations to work through her own complex explorations of identity and cultural difference, she subverted the power of the Western male gaze on the colonized nude female body.

The Turn to India

By the end of 1934, Sher-Gil returned to India (she had temporarily moved to India with her family in the 1920s due to financial difficulties and political unrest in Hungary), expressing that her prolonged encounter with Europe’s modernist art scene incited in her a need to develop her own style and point of view. She felt that the colors, light, and natural environment in India would help to improve her painting.

When she painted the self-portrait in 1934, Sher-Gil was herself a colonial subject since India was still a British possession despite intense and ongoing efforts for self-rule. Sher-Gil, who died at age twenty-eight, would not live to see India’s independence from the British Empire in 1947. While she disrupted the structures of power normally held by the imperial West in reformulating Gauguin’s colonialist views for her own purpose, her affluent, aristocratic background and international mobility complicated her identity and distinguished her from a subject of the colonial crown in India who had little to no agency. Her relatives even owned a major sugar plantation where her family briefly stayed, and where her husband, Victor Egon, had worked as a medical officer of the dispensary attached to the factory. That the sugar industry, encouraged by the colonial state, benefited Indian capitalists like the artist’s family while placing millions of common workers in indentured servitude further distances her from the subjects whom she portrayed.

Amrita Sher-Gil, Bride’s Toilet, 1937, oil on canvas, 146 x 88.8 cm (National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi, India)

Perhaps aware of her global and Eurocentric identity, she replaced her Western fashions with traditional sarees, painted Indian peasantry, and brightened her color palette to reflect her cultural surroundings. As Gauguin had done in Tahiti, Sher-Gil too carefully cultivated a persona to make her mark in the art world. In Sher-Gil’s case, it was imperative that she be accepted as an Indian modernist, as seen through her bold claim that while European modernism fell within the purview of Matisse, Picasso, and other avant-gardists, “India belongs to me.” [4]

Indeed, the murals of Ajanta, sculptures and frescoes of temples and palaces, and Mughal and Rajput miniature painting inspired new creative avenues. As Sher-Gil progressed in her painting, she went even further than Gauguin and Western modernists in the simplification of forms, reduction and stylization of shadows, and elimination of extraneous details, focusing only on the monumentality of the Indian figures, the central interest of her compositions. Her work evolved to merge Western and Eastern stylistic and formal vocabularies and subject matter and led to the artist’s legacy as a pioneer of modern Indian art.

Notes:

[1] The Japanese identification is based on Saloni Mathur’s “A Retake of Sher-Gil’s Self-Portrait as Tahitian,” Critical Inquiry 37, no. 3 (2011): pp. 515–44.

[2] Denise Proutaux quoted in N. Iqbal Singh, Amrita Sher-Gil: A Biography (New Delhi, India: Vikas, 1984), p. 25.

[3] Sher-Gil, letter to Karl J. Khandalavala, 16 May 1937, in Amrita Sher-Gil (Bombay, India: New Book Company, 1944), 1: p. 375.

[4] Amrita Sher-Gil quoted in Deepak Ananth et al, Amrita Sher-Gil: An Indian Artist Family of the Twentieth Century (Prestel Pub, 2007), p. 13.

Additional Resources

Elizabeth C. Childs, “Taking Back Teha’amana: Feminist Interventions in Gauguin’s Legacy” in Gauguin’s Challenge: New Perspectives After Postmodernism, edited by Norma Broude (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018), pp. 246–67.

Geeta Kapur, “Bodies as Gesture: Women Artists at Work” in When Was Modernism: Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India (New Delhi, India: Tulika Books, 2000), pp. 3–60.

Saloni Mathur, “A Retake of Sher-Gil’s Self-Portrait as Tahitian” in Critical Inquiry, vol. 37, 3 (Spring 2011): pp. 515–44.

Yashodhara Dalmia, Amrita Sher-Gil: A Life (Penguin Books, 2006).

Amrita Sher-Gil, Amrita Sher-Gil: A Self-portrait in Letters & Writings, volume 1, edited by Vivan Sundaram (New Delhi, India: Tulika Books, 2010).

Amrita Sher Gil, “Evolution of My Art,” in Amrita Sher-Gil: A Reader, edited by Yashodhara Dalmia (Oxford University Press, 2014).

Tariro Mzezewa, “Overlooked No More: Amrita Sher-Gil, a Pioneer of Indian Art,” in The New York Times (June 20, 2018).